The Unwritten Rules of Black TV

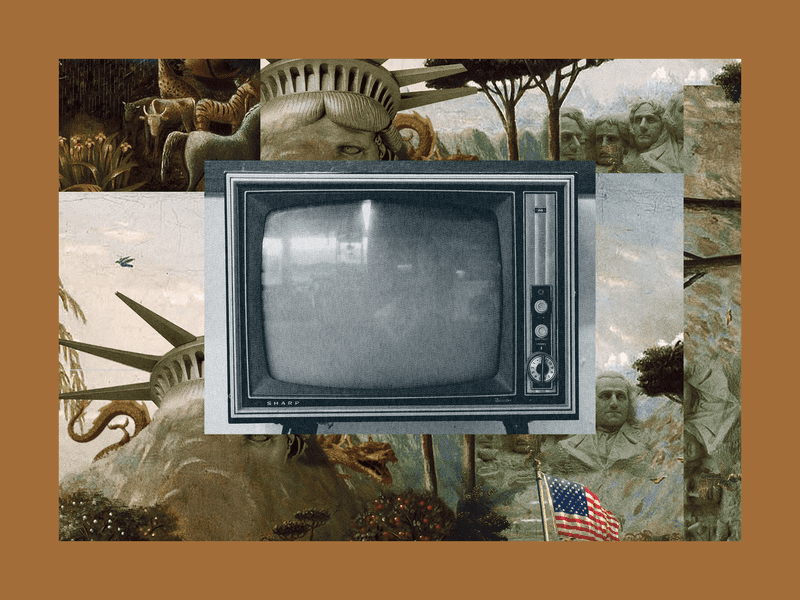

(The sound of an old TV crackles on. The channels change loudly and with plenty of static as car alarms, a laugh track, and an abruptly disrupted monologue play for seconds.)

Julia Longoria: I don’t know what it is about the American sitcom …

(More laughter from an imaginary audience.)

Longoria: … that just has a way of seeping under our skin.

(A new laugh track plays.)

Longoria: I think for those of us who grew up watching TV, we all have that one show that—to some extent—taught us what life could look like. Or, maybe, what we thought life should look like.

(The theme song to ¿Que Pasa, U.S.A.? plays. A singer croons, “Say hello, America! We are part of the new U.S.A.!” as background singers echo.)

Longoria: For instance, my parents used to watch this show—it was amazing—called ¿Que Pasa U.S.A.?, [The theme song plays up.] which was essentially a mirror for them. It was about Cubans who arrived in Florida.

(The music dissolves and transitions into a fast-paced, piano-led jazz bit.)

Longoria: And there’s this one episode they would always play for me as a little kid, where the kids in the show try to hack the U.S. citizenship test.

Violeta: My mother figure out that on the yes-and-no questions, there’s 80 percent chance that the right answer will be “Yes.”

Carmen Peña: Hey! That’s a good one!

Longoria: And, when they practice the questions with the grandparents on the show, antics ensue.

Carmen: Are you willing to take full oath of allegiance to the United States?

Abuelo Antonio: Yes.

Carmen: Have you ever engaged in prostitution?

Abuela Adela: (Very, very enthusiastically.) Yes! [A beat as the audience laughs.] I like it very much! (Uproarious laughter from the audience.)

Longoria: And I bet, for a lot of recent immigrants, it was pretty powerful to have a sort of mirror like that—to see their experience fictionalized and joked about on American TV.

(The music plays out.)

Longoria: And then, inexplicably, for my little sister—who grew up in Miami—the show that she watches—that she still falls asleep to—is Reba.

(The theme song for the show Reba plays.)

Longoria: The show about a single mom in Texas.

(A new voice laughs.)

Longoria: I was talking about this recently with my colleague, Atlantic staff writer Hannah Giorgis.

Hannah Giorgis: Listen, I get it! My roots are also firmly planted in the past. (Both laugh.)

Longoria: She’s been thinking deeply over the last few months about some of the TV shows that she was raised on.

Giorgis: My show was Living Single.

(The theme for the show Living Single plays. A chorus sings, “We are living—living single.”)

Giorgis: Which is a sitcom that follows four young Black women who live in—Well, three of them live in one Brooklyn brownstone, and one of them is technically a neighbor, but she’s always over at the house, all the time.

Maxine Shaw: (Knocking on the door.) Heyyy! Max in the hou-se! (Audience laughter.)

Giorgis: And that was the character, actually, who I latched on to the most. Her name is Maxine Shaw.

Maxine: Maxine Shaw, your honor. Counsel for the plaintiff.

Kyle Barker: Warn the townspeople; the beast is loose. (The laugh track plays.)

Giorgis: Maxine is, of course, a high-powered lawyer. She does well in the courtroom and really cares about her work and what it is that she does, especially when she’s defending women.

Maxine: Today my look and my law were fierce! I got my client the house, the Winnebago, alimony, and 70 percent of all the assets he tried to conceal.

Giorgis: And then we see this other side of her in a recurring bit on the show where the characters who live in the main brownstone will get back home, or they’ll walk into a different room, and Maxine is just sitting there eating their food.

Maxine: Hey! Max in the house! What’s up? What y’all got to eat?

Khadijah James: Here, try this. (Max tries it and immediately spits it back out loudly as the audience laughs.)

Giorgis: As much as they joke and make fun of her for it, they all love her. That’s very clear.

Longoria: And what did the show and those characters mean to you at the time?

Giorgis: I remember thinking that they were really cool, [Both laugh.] which is showing, uh, you know, the fact that I was a child, right?

Longoria: Totally!

Giorgis: I was like, “Wow! They live in a house, and it’s in New York!” But I don’t even know that I thought about their kind of bigger-picture significance so much as I thought that I wanted to do that, and be them, and, like, you know sit around a table and cook with my friends, when I had my own apartment one day, like, in the big city, right? (Chuckles.)

Longoria: Are you living out that dream now?

Giorgis: (Laughs, but only slightly self-consciously.) I know! It’s so corny to say that back and to realize that, like, Oh boy! I sure do live in Brooklyn! (Both laugh.)

(A light snare beat plays under a crackly, introspective, and somber keyboard melody.)

Longoria: Even if Hannah didn’t know it back then, Living Single—which starred a Black cast, was written by Black writers—was part of a bigger moment in American TV.

Giorgis: In the mid-’90s through the early 2000s, it felt like there were a ton of Black characters on TV every day.

(The somber music ends. A series of TV theme songs plays.)

Giorgis: You had your Steve Harvey Show. [Each upbeat theme plays, announcing the show’s title, as she names it. The transitions from one to the next are seamless.] I was a big fan of Moesha … Sister, Sister … Smart Guy—all these different types of shows. [The music plays under for a moment and then echoes out to nothingness—just a ringing sound.] And then, in the early 2000s, it felt like they started disappearing, one by one. And then, by 2006 or 2007, there just weren’t that many Black characters on TV at all, because those characters hadn’t—and those shows hadn’t—been replaced by new ones.

(The introspective music returns.)

Longoria: And the question Hannah and many of us viewers were left with was “Why?” Shows by Black creators had been made for decades by that point. Before the ’90s, we had shows like The Cosby Show and A Different World. Before that, The Jeffersons. So why did Black shows seem to suddenly disappear for about a decade?

And that question feels especially puzzling right now—because Black TV is, all of a sudden, back.

Giorgis: People talk about this moment we’re in as a kind of golden age for Black television.

Longoria: In the streaming age, after the racial reckoning of the last year, Black creators are finding new opportunities again.

So, now, as a critic and journalist, Hannah set out to figure out what happened over the last 50 years of Black TV history. What went on in those writers’ rooms? How did the shows she loved as a kid get made in the first place? And why did they disappear in those dark ages?

(The music ends with an abrupt final note.)

Giorgis: So I talked to dozens of writers who had been in a bunch of those rooms and who had seen how all of this has unfolded and evolved over the last several decades. And one of the people I spoke with whose experience on multiple different fronts really stayed with me and really struck me, um, was Susan Fales-Hill.

Susan Fales-Hill: There is an actual entertainment-industry history. And I—I’ve actually seen an unbelievable evolution.

Longoria: Susan Fales-Hill was a writer who got her start on The Cosby Show. Her mom worked in the industry for decades before that. And Susan’s still working in the industry today. She’s someone who’s able to kind of tell the whole story of the history of Black TV.

(A light atmospheric sound—dust motes of electronica—float through the air underneath Giorgis’s narration.)

Giorgis: Because she wasn’t just there on one show or in one writers’ room. It really seemed like, for the entire kind of 50 years of TV that I was interested in, she was there in that history somehow and could speak to the power dynamics at play—the peaks and the valleys—and all of that across decades, including the dark ages.

(A crackle, a click, a TV is on and the synthesized dust motes swirl in the sonic air.)

Longoria: This week on the show, Atlantic writer Hannah Giorgis talks with veteran TV writer Susan Fales-Hill, and traces the history of an invisible power behind the scenes of American TV: how writers’ rooms over the last 50 years shaped what we watched, what we talk about, and how we understand ourselves.

(A change in pitch. The TV channels change, restless and wandering.)

Longoria: I’m Julia Longoria. This is The Experiment, a show about our unfinished country.

(After a beat, the music is swept away in a blip.)

Giorgis: Susan’s entry into the TV landscape was pretty unusual, uh, in some ways destined, almost.

Fales-Hill: Well, my first introduction to show business was sitting on a piano while my mother rehearsed and her accompanist was playing. My mother was a singer, actress, and dancer. Her name was Josephine Premice.

(Josephine Premice sings the song “Mama” in Italian in a 1967 recording.)

Fales-Hill: I was kind of weaned by the great divas of yore: people like Cicely Tyson, Eartha Kitt—who was her roommate when they were both young—and Diahann Carroll, [Giorgis laughs.] who was her best friend.

Giorgis: Susan’s mother was best friends with Diahann Carroll, and Diahann Carroll plays a huge role in the earlier histories of Black TV. She was the star of a show called Julia, which premiered in 1968.

Julia Baker: (Over a lush string arrangement.) This is a beautiful breakfast, Corey, and I thank you.

Corey Baker: I’d thank me too!

Giorgis: It was the first show on prime time that starred a middle-class Black woman in the forefront of the series. She played a nurse who was widowed when her husband went to war.

Julia: It’s been a long time since a man prepared my breakfast.

Giorgis: Who’s still raising a child while working, and managed to be—as is expected of any character being played by Diahann Carroll—extremely glamorous [Laughs.] in the process.

Corey: Did Daddy used to fix breakfast for you, Mama?

Julia: (Sighing.) Sometimes … when he wanted something.

Giorgis: So the era of TV that Susan grew up witnessing was one in which Black people were not leading writers’ rooms.

And, to the extent that there were any shows led by Black casts, often they were created by white people. That was definitely the case with Julia. And those characters tended to conform to white audiences’ expectations.

Fales-Hill: For me, growing up, watching television, I was very frustrated because Black people were presented in very monolithic ways.

Giorgis: One day, Susan’s mother was having dinner, and Bill Cosby happened to be there—and asked if Susan had any interest in being a comedy writer.

Fales-Hill: And then I was offered an apprenticeship on The Cosby Show, and that’s what started me on the path of being a professional writer. It was very intimidating. And I was right to be terrified, because it was an all-male room [Laughs.] and they were—uh—not necessarily looking to welcome with open arms a young woman that they, in their defense, had not picked.

Giorgis: So Susan’s job was to assist the writers. There were both white and Black writers on the show, but they were almost all men.

Fales-Hill: So I just showed up every day and volunteered every day to make myself useful. So, finally one day, they gave me a task, which was “Do some research on car insurance in Brooklyn”—since the show was set in Brooklyn Heights. And you would’ve thought someone had given me the Rosetta Stone or something.

So, I don’t even know where I found the information, but I did—and wrote up a three-page report about it. And then they realized, Oh! She can actually be useful. So then they let me in the room. And then I was the person who wrote down everything they said. I—I was the scribe. And some people would say, “Oh, well, that’s secretarial work!” Well, secretarial, shmeck-retarial!

I was there listening to these people as they were creating the shows that have become iconic.

(A clip from The Cosby Show plays.)

Clair Huxtable: What do you want for breakfast?

Rudy Huxtable: Cereal!

Clair: “Cereal,” what?

Rudy: Cereal … and bananas!

Clair: “Cereal, bananas,” what?

Rudy: Cereal, bananas, and milk! (The audience laughs.)

Clair: “Cereal, bananas, milk” … what?

Rudy: (After a long pause.) … In a bowl! (The audience cracks up.)

(The clip ends.)

Longoria: Did you watch The Cosby Show growing up?

Giorgis: I did. I watched The Cosby Show—like a lot of young people, I think, did—with family. It really was that sort of show that we could all gather around the TV and enjoy, not necessarily because it was a Black series, but because it was one about a big and rambunctious and sometimes awkward—but always loving—family. Um, and I know that my parents very much loved the values [Chuckles.] being instilled, and that there were these loving and stern parents who insisted that the kids go to school and be sort of morally upright in ways that very much resonated with my very Christian parents. (Chuckles.)

Longoria: And this show, at the time, was pretty unusual, right? Like, run by a Black man, starring a Black cast. How did it get created? Did you get a sense for how the writers’ room might’ve been different from ones in the past?

Giorgis: Yeah. It seems, based on a lot of the conversations that I had with people, that there was some leeway in the Cosby writers’ room based on the star power of Bill himself.

Fales-Hill: Mr. Cosby was the voice over all, uh, that happened there. And those writers were—they were enlightened men when it came to race. They may not have known everything, but they treated these characters with enormous respect.

Giorgis: The writers’ room may have been on board with Cosby’s vision for the show, but Susan remembers that was not always the case with the network executives.

Fales-Hill: I mean, one of them said, “This isn’t a real Black family.” And I said, “Why?” And he said, “Well, they live in that house.” And I said, “Well, my Haitian grandfather lived in a house like that. He was an immigrant and bought that.” [Laughs.] “What are you talking about?”

Giorgis: And the suggestion, of course, was that they are too wealthy—they’re too established socially—to be “relatably” or “believably” Black.

Fales-Hill: And I thought, All right. This may represent not the majority of African Americans, but neither does a show like Murphy Brown. What—what percentage of the white population did Murphy Brown represent?

(A fluttering synthesizer plays for a moment, flourishing over a slurring electronic horn line that drags the notes out in a slow drawl.)

Giorgis: So, in keeping with how much of an influence Cosby had on what the show could do around wealth and its representation of a comfortable upper-middle class Black family, he also had a lot of say over how it did or didn’t handle issues of race.

Fales-Hill: Mr. Cosby did not believe in calling out the race of the Huxtables. Their identity was palpable through the art on their wall, the ways in which Phylicia looked at her children and looked at him, the fact that they’d been to these historically Black colleges. There were many, many elements, but they never sat around talking about Blackness.

(The music fades out.)

Longoria: You know, something I always think about and grapple with as someone who loved The Cosby Show as a kid [Chuckles for a moment, uncomfortably.] is, um, how we think about that show now, after we’ve seen all the allegations against the creator, Bill Cosby. How does Susan think about that?

Giorgis: Yeah, I mean, something I knew going into this story was that it would be impossible to separate the legacy of The Cosby Show, including all of the ways it had changed TV—and Black TV especially—from the legacy of Cosby himself, who, as we all know, was convicted of felony sexual assault, and recently had that conviction overturned on a technicality. And that’s something that Susan said she still thinks about and still struggles to describe, even today.

Fales-Hill: It’s devastating to—to hear those stories and to read the stories of these—these women. And—and my heart goes out to absolutely every person in this situation. How do I reconcile it? I don’t. I’m 59. I’ve grown up around a lot of very complicated people. So, for me, nothing excuses what happened. Nothing does. However, I don’t believe that what happened should [Searching for the words for a moment.] diminish what the show meant to America and what that show did for America.

(A new bit of background music plays: a stumbling kick drum and a plinky chord-based keyboard melody hop and skip and jump along underneath the narration.)

Giorgis: She felt like her primary job in the Cosby writers’ room was to learn. And so it wasn’t really until she left that room and went on to write for the spin-off of The Cosby Show, which was A Different World—the series that followed Denise Huxtable to college at Hillman, a fictional historically Black university—that environment is where Susan really got to spread her wings more as a writer.

Fales-Hill: And that was really joyous. And people—especially in those days—would get very upset with Black shows because they didn’t feel represented. And on A Different World, we had a chance to show everyone from a Mr. Gaines …

Mr. Vernon Gaines: (In A Different World.) Let me give you some advice.

Fales-Hill: … who ran the pit …

Mr. Gaines: (In A Different World.) Are you crazy? [Audience laughter.] Well, you must be! Driving the woman you love to some other man—in your own car! [The laugh track.] Well, I hope he’s gonna pay for the gas! (More laughter.)

Fales-Hill: Then, you know, Colonel Taylor, who was a conservative …

Colonel Bradford Taylor: (In A Different World.) Miss Gilbert!

Fales-Hill: … and that military man.

Colonel Taylor: (In A Different World.) I’d like a little less flippancy, more effort—and you might think about getting a tutor.

Whitley Gilbert: (Continuing in A Different World.) No, I might not!

Fales-Hill: And then, you know, Whitley, who was the ultimate bougie princess.

Whitley: (In A Different World.) Colonel Taylor, [Laughter.] I appreciate what you’re trying to do, but the only math problem I’ll ever have to solve in life is “How many batteries will it take to put in my lil’ pocket calculator?” (Laughter.)

Fales-Hill: So many Black women have come up to me and said, “Oh, that’s me!” Or, “Oh my God! That was my roommate at Spelman!”

Giorgis: In the second season of A Different World, Susan actually asked Diahann Carroll—her mother’s friend—to come on the show and play Marion Gilbert, the mother of the show’s southern debutante, Whitley Gilbert. So, a role befitting Diahann Carroll.

Marion Gilbert: Ladies, this bedspread is positively at war with those curtains! (Laughter.)

Whitley: Mother, this is Kim’s bedspread. (Laughter.)

Marion: Oh! Well, then. How could you have known, Carol?

Fales-Hill: And I remember, at the end of her first taping, she gathered the cast and she said, “You don’t understand what it is that you’re living, but I want you to recognize it.” And she said, “When I was first on studio lots in the ’50s, I was the only Black woman.” She said, “Look at this: You have a Black directing executive producer, you have Black writers, you have a Black head writer, and you walk on this lot like you own it.” She had a big jeroboam of champagne and gave everybody champagne.

Giorgis: Has there ever been a more glamorous person on this planet?

Fales-Hill: No, no. And she was that way in private life!

(A soft, lush soundscape plays. As Giorgis narrates, the soundscape dissipates.)

Giorgis: In the first five seasons of A Different World, there wasn’t a ton of objection earlier on to some of the issue-focused episodes—like the episode about date rape, for example. But there’s a real tension around the episodes that would become the first and second episode of the final season. And those two episodes followed Dwayne and Whitley—who were newlyweds at the time—on their honeymoon in Los Angeles.

Fales-Hill: And Whitley somehow ended up on her own and stuck in the middle of the Los Angeles riots—

Whitley: (In A Different World, over the sounds of helicopters and police sirens.) Hello! Hello? This is Whitley Gilbert! Um …

Fales-Hill: —and a witness to much of what went on—

Whitley: (In A Different World.) Yes, I’m at this Melrose Court in, uh … Could you send me a limo right away? (A car honks.)

Fales-Hill: —uh, which then led to her telling the story back at the dorm and all of our characters having their responses to that moment.

(Clip plays.)

Dwayne Wayne: You know, if we had strong, Black leaders, none of this would have happened.

Unidentified voice: We do have strong Black leaders: Maxine Waters, Jesse Jackson, Brother Malcolm—

Wayne: Man, you need to check an obituary column! Malcolm died in 1965!

(Clip ends.)

Fales-Hill: That was the George Floyd of its day, obviously: Rodney King and then, uh, what precipitated the riots, which was the not-guilty verdict for those who had beaten Rodney King and had been caught on video.

The show came about because the uprising happened during our hiatus. And when we got back to the writers’ room, actually two of our youngest writers, Reggie Bythewood and Gina Prince-Bythewood—who are both now legendary in their own right—really made a plea for us to address this. ’Cause we always addressed topical issues head-on. And they said, “If we don’t do it, who will? And we must.” And so we did, to the consternation of the network, who were really trying to put this behind them and did not see this as a ratings bonanza. And I believe, to this day, that it cost us our—another season.

(A clunky, industrial beat plays around somber piano music.)

Giorgis: I think the general discomfort with these episodes in particular reflected a real sense of anxiety about what it looks like when Black people tell stories that are not easily digestible, quick references to racism in which there’s no real good or bad guys, but, just, things happen. And the idea that an issue directly affecting Black people would be covered through a lens that is unmistakably Black and that doesn’t shy away from the idea of blame—or the idea that there are going to be viewers across the country seeing this who might be uncomfortable with some of the conclusions—really was unsettling for some people.

Longoria: So when A Different World ends, where are we in the bigger story of the history of Black TV? Like, what happens next?

(The music fades out.)

Giorgis: Right after A Different World goes off the air, we start seeing Living Single, which is a show created by Yvette Lee Bowser, who was in the A Different World room. Sister, Sister comes out in ’94, and that’s from Kim Bass, the sitcom that followed Tia and Tamera as long-lost [Laughs.] twins who find one another in a mall. Incredible concept. [Both laugh heartily.]

And then, you know, you have—you have a slate of sort of young-person-focused sitcoms that come up. There’s Smart Guy, Moesha—that period from about ’94 or so through ’98 was really rich in that specific, coming-of-age-type sitcom space.

Longoria: And a lot of those writers came out of the Different World writers’ room, right?

Giorgis: Yeah. There’s so much overlap and so much interpersonal and kind of community support for one another that helped a lot of people break through, because they had one another.

Longoria: And, um, what—what happened after that?

Giorgis: Well, this is where we get to that period that I noticed as a kid. Moesha ended in 2001. Soul Food went off the air in 2004. And there weren’t a ton of shows featuring Black characters that took their place.

Susan told me that this was a difficult time for her too. She was pitching ideas, and kept being told that they needed to be more “relatable.” [Laughs once.] And eventually she just decided to take a break from TV writing.

So many of the people that I talked to remembered feeling like they just couldn’t get their ideas through at all.

Longoria: In your reporting, did you find a reason why—like, economically or, like, industry-wide—why people like Susan were having a hard time getting their ideas through?

Giorgis: So, as broadcast networks were trying to compete with cable networks that were popping up and pulling away from their audiences, they really doubled down on wanting to make shows—whether they were sitcoms or dramas, often procedurals—uh, that were going to attract really big audiences.

And, in order to pull in the broadest audiences possible, that often meant that they were focusing on shows that were led by white actors, that were produced by white writers, directors, et cetera. And, of course, there are a handful of exceptions, but for the most part, Black writers who often were shut out of those rooms because there was a belief that they couldn’t write “white”—whatever that meant at the time, whatever that means now—those writers were shut out of the industry altogether if they couldn’t get into the rooms where the few Black shows still being made were produced.

(Light, high synths pulse over what sounds like a PVC pipe organ.)

Longoria: After the break, how Black TV comes back.

(The music winds down.)

(The break.)

(The sounds of a tape rewinding, changing TV channels, a laugh track, static.)

Longoria: I’m Julia Longoria. This is The Experiment.

(The TV clicks off, taking the static with it.)

Longoria: And we’re back with Atlantic writer Hannah Giorgis. She grew up watching iconic TV shows from Black creators and writers, like Living Single, Moesha, Sister, Sister. And then, in the early 2000s, they disappeared. Black writers struggled to get into writers’ rooms. The TV shows they were pitching weren’t getting made. But in 2005, something started to change.

Giorgis: What’s interesting is a lot of people attribute the slow crawl [Laughs.] out of the dark ages to the popularity of shows made by Shonda Rhimes. Shonda Rhimes’s first big show is Grey’s Anatomy, which premiered in 2005.

Cristina Yang: (Over goofily blundering early-2000s sitcom music, which loops to create a sense of movement.) McDreamy’s being McDouchey. He’s making me stand at the back of the OR while he reattaches Rick’s fingers. But I can’t even touch a retractor. I hate him. (Fades out.)

Giorgis: It really took, you know, a long-running (at the time) medical series with a very diverse cast—a show that wasn’t billed as a quote-unquote “Black show,” but that was just a noticeably diverse multiethnic ensemble cast, produced by a Black woman. It took that leading into Scandal, and, from there, Black-ish, for the dark ages to really start shifting to being in the past and not just the state of play.

Longoria: And what contributed to that rise?

Giorgis: As we see with a lot of Black TV history, you know, in Shonda’s case, and in many other people’s since her, it has taken the co-sign of another prominent Black person to bring them on board so that they get that first initial opportunity.

Shonda has been that person for people. Issa Rae has now been that person for people. But oftentimes it’s that first entry point that is the hardest and that—where most people find that established industry veterans who don’t necessarily find their experiences relatable or compelling don’t always take a chance on them.

(Spacious, wavy music plays.)

Giorgis: Now we’re seeing an explosion of television shows created by Black writers and directors. Today, there’s Insecure, Atlanta, Dear White People, P Valley—and just so many more. Streaming’s played a big role in that, in part because feedback from viewers is more direct than ever.

Susan herself is part of this too. She’s back in a writers’ room, this time as an executive producer on Lena Waithe’s show Twenties, which is on BET.

Fales-Hill: So let’s be clear. I’m—I’m the midwife, [Putting on a British accent.] “Call the midwife!” It’s Lena’s baby. [Both laugh.] I didn’t create it. It’s hers. But it’s about a group of young Black women in their 20s, navigating, um, Hollywood in this kind of golden age.

Hattie: (In Twenties.) I’m Black, and I’m gay! Hollywood should be knocking down my door! (Fades under.)

Fales-Hill: And the central character is a young Black queer woman, which, again, is—is groundbreaking and revolutionary.

(Another clip from Twenties plays.)

Hattie: What did you like about it?

Nia: I like that it’s about Black love!

Marie: And I am just glad it exists.

Hattie: Those are not good reasons to like a show!

Marie: We need to support Black shit!

Hattie: No, we should support good shit that just happens to be Black.

(The clip ends.)

Fales-Hill: And something I don’t think—Actually, when I look back at A Different World, I mean, we never even said the word queer. We had no queer characters. So it’s just a new day. And also, tonally, there’s a lot more freedom. I came from the “three jokes per page,” [Both laugh.] “every scene ends with a button,” and that’s no longer the mandate, and that’s no longer what people find funny. And in terms of the writers’ room, it was very exciting because—not by design—but I ended up staffing all people of color.

(A dreamy, heavenly synth plays, light and wild. It slowly fades under as Giorgis speaks.)

Giorgis: When Susan talks about this experience, it’s hard not to think about her bringing Diahann Carroll onto the set of A Different World. That when Diahann looked around and saw so many Black actors, that was a big deal then. Leading a show like Twenties, having this experience now, is a big deal for Susan.

(The music slowly fades out.)

Longoria: I guess my question for you, Hannah, as someone who thinks about this really deeply, is, when you look at all these changes that have happened—starting back when Diahann Carroll was starring in Julia in the late ’60s all the way through to this new golden era we’re living now of Black TV—what does it tell us about the culture and about the power structures that make shows like A Different World and Black-ish possible?

Giorgis: I think what’s clear and what remains true is that a lot of the moments that feel like big social and cultural progress have a real element of economic motive behind them. And as the demographics of the country continue to shift, it’s clear that viewers are, you know, asking for a broader array of shows that—that are more thoughtfully addressing certain topics, that are the kinds of things they want to engage online or talk about with their friends, and that the older models, um, of assuming relatability solely from the perspective of a straight white man or a set of white friends moving into a city like New York and interacting with no people of color [Laughs.] just doesn’t—just doesn’t work anymore. It doesn’t work from a storytelling perspective, and it doesn’t work economically. And I think that we’ll see more shifts toward just a more interesting TV landscape.

Longoria: And going back, I guess, to where we started: How do you think this moment compares to the one that you grew up in?

Giorgis: I think it’s really exciting that there are enough Black shows on TV for younger viewers especially to decide that there are shows they’re not interested in and don’t care about.

Longoria: (Laughs.) Yeah.

Giorgis: You know, I—I think that the idea that you can be a viewer whose decision matrix is not just “Okay, well, are there any Black people on this?” but can be “I don’t know about the humor style of this show. It doesn’t quite work for me. So I’m going to watch something else,” right? That there’s horror series and films and all these things that are allowing for a kind of diversity within the massive category that is Black TV.

Longoria: Yeah. It’s shows that are telling stories of a person, not just like, “Oh, here’s a—“ [Chuckles.] whatever, “the Black experience.” (Laughs lightly.)

Giorgis: Right. Right. And I—I think in general, I find myself most interested by shows that are about characters who are Black, as opposed to shows about Blackness. And it seems like there’s more of that now than even in the last five years or so. And that’s exciting to see, that there can be a bunch of different shows about Black characters that very rarely touch on racism—not because it doesn’t affect people’s lives, but because the characters have so many things going on that their lives are not defined by this force that exists outside of them.

(A quavering synthesizer plods along as another hums around and through it.)

Natalia Ramirez: This episode was produced by Meg Cramer. Reporting by Hannah Giorgis. Editing by Katherine Wells and Julia Longoria.

Fact-check by Jack Segelstein. Sound design by David Herman, with additional engineering by Joe Plourde.

Music by Tasty Morsels and Nelson Nance.

Our team also includes Tracie Hunte, Peter Bresnan, Emily Botein, Gabrielle Berbey, Alina Kulman, and me, Natalia Ramirez.

This episode is part of The Atlantic’s “Inheritance” project, about American history and Black life.

You can read Hannah Giorgis’s article “Most Hollywood Writers’ Rooms Look Nothing Like America” and more on our website, www.theatlantic.com/experiment.

And if you’re enjoying this podcast, please take the time to rate and review us on Apple Podcasts or wherever you listen.

The Experiment is a co-production of The Atlantic and WNYC Studios. Thanks for listening.

(The music plays out.)

Copyright © 2021 The Atlantic and New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.