Episode 3: The Two Wars

KALALEA: Before we start this episode, I want to let you know a little bit about what you’re going to hear. Yes, this is a series about the massacre in Tulsa. But it’s also about what came before it -- the crimes that led up to the attack. Including the lynchings that terrorized Black people all across the country. We’ll cover that in today’s episode, as well as other scenes of graphic violence, hatred, and racially offensive language.

[LONG BEAT]

[old war music]

KALALEA: It’s April, 1917. President Woodrow Wilson asks Congress to declare war on Germany.

Woodrow Wilson (Actor): The world must be made safe for democracy. We are but one of the champions of the rights of mankind. We shall be satisfied when those rights have been made as secure as the faith and the freedom of nations can make them.

Adriane Lentz-Smith: He’s calling in this incredibly idealized and idealistic language -- And what he did not quite on purpose was to open up a space for people [...] to use his language for their own civil rights activism.

KALALEA: Adriane Lentz-Smith is a professor of history and African and African-American studies at Duke University.

Adriane: Black freedom fighters on American soil are like, okay -- here is this moment when we might be able to push our cause.

KALALEA: The cause is... not being treated like second-class citizens.

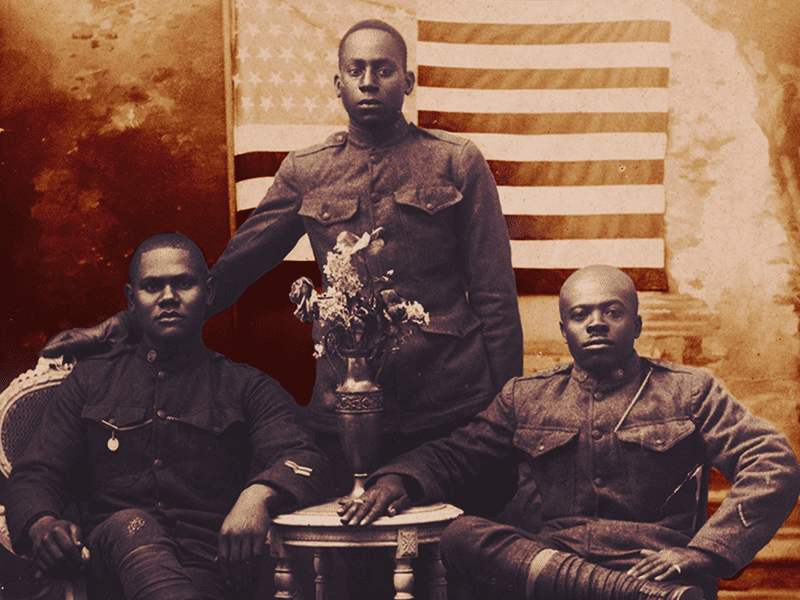

The United States declared war at the height of the Jim Crow era. But Black Americans thought this war, World War I, might actually present an opportunity.

Adriane: There’s such a link in this period between soldiering and citizenship, between military service and the prerogatives of being a citizen. There were folks saying, Like, we can’t have a freedom struggle if we don’t have people who are willing to put, like, skin in the game.

KALALEA: Just a few months later, in the fall of 1917, a man named B.C. Franklin is standing in a little town park in Eufaula, Oklahoma. He’s giving a speech to a large group of young Black men, urging them to enlist.

He would later write about that speech in his memoirs… which we’re adapting for this podcast.

FRANKLIN (Actor): Master of Ceremonies, and fellow citizens: We are met together here to urge upon you--young men--the imperative necessity of immediate enlistment, and to bid farewell…

KALALEA: Franklin is of African and Native-American descent. He’s a prominent lawyer, who’s working in Black communities around Oklahoma. He’s smart, honest, and has cheekbones that could cut glass. He’s trying to convince Black men that this is a war worth fighting for.

FRANKLIN (Actor): Young men, you are here in answer to your country’s call to duty. Yours is an honorable heritage; yours is a remarkable reputation to uphold and defend. You have come from the loins of a race that has never produced a traitor, nor a coward when summoned in the defense of this nation and its flag…. “On to Berlin!”

[Applause]

FRANKLIN (Actor): When I had finished my little speech, a young colored couple made their way through the vast throng to the speaker’s stand. The fine-looking man was dressed in the uniform of his country. He stood tall, striking, and his eyes flashed when he spoke…

He introduced himself as John Ross and thanked me for my speech.

“I enlisted for service,” he said. “Within thirty days, we’re settling sail for Europe.”

And so young Ross went to Europe and fought for his country.

He... was simply a cog in the great machinery of war… Life -- sordid at times -- is made up of many changes and vicissitudes.

KALALEA: Men like John Ross would encounter mistreatment during their service, and when they returned home to Oklahoma, it got worse.

It would change what many believed about defending the nation and its flag. And about what it would take to preserve their own liberty... when the war came home.

[THEME MUSIC]

KALALEA: From The History Channel and WNYC Studios, this is Blindspot: Tulsa Burning.

The story of a country set on fire… and the people who fought to save it. I’m KalaLea.

Episode 3: The Two Wars

In the years before the Tulsa massacre, the U.S. was gripped by violence on multiple fronts -- that’s what we’ll be exploring in this episode.

Remember what President Wilson said about Americans being “one of the champions of the rights of mankind”? Those words were read in segregated towns and cities throughout the country -- places where it was commonplace for white people to terrorize and sometimes lynch their Black neighbors. Their excuse for lynching? Often, it was some alleged indiscretion -- could be as little as walking too closely behind a white lady. Could be an accusation of rape or murder. Regardless, there would be no trial. Just vigilante violence.

Adriane: “I think for people who don’t know a lot about lynching, we tend to think of like, 1960s or 50s-era lynchings which tend to be more secretive, right, or done by a couple of people under cover of the night and nobody talks about them again. What we have to remember about the lynchings of the 1910s and 1920s or so is that these were almost carnival events.

In some instances, there was transportation run from town to the site of the lynching, people would sell lemonade. They were in effect advertised ahead of time, right. Children would be there, families. And they would murder, burn, shoot, what have you, people in really horrible ways, and often kind of take pieces of their bodies as souvenirs.

[MUSIC - hymn fades up]

Adriane: In the Spring, after the US declared war, in Memphis, there was a lynching of a man named Ell Persons. He had been accused of raping and murdering a white teenager. It seems very questionable, they had not enough evidence really to arrest him, nevermind call him guilty.

He was taken from the jail, taken to the outskirts of Memphis. A crowd of hundreds, maybe more gathered, they sang hymns. They burned him, placed an American flag over the place where they'd burned him. And then some men took his head and dropped it in the middle of Beale Street, which was the Black business district, uh, of Memphis as a way of saying this, isn't just about Ell Persons. This is about all of you.

KalaLea: You mentioned the singing of hymns during these lynchings...

Adriane: So the one I remember for Ell Person is “Nearer my God to Thee.” Which is just again, it’s so --

KalaLea: Yeah, Nearer my God to Thee, I mean really, while you’re torturing somebody?

Adriane: So chilling.

[MUSIC - hymn fades out]

KALALEA: And whites didn’t just lynch men. Ida B. Wells reported extensively about the torture and lynching of hundreds of women and children.

In Georgia, a woman named Mary Turner publicly expressed outrage at the lynching of her husband; and, the next day, she too was lynched. She was 8-months pregnant.

With the US entering the war, a debate broke out within Black intellectual circles about whether African-Americans should actually be putting their lives on the line to protect this democracy that refused to protect them.

Adriane: You see people writing in newspapers or speaking in barbershops who say things like, I’m far more worried about the Huns of America than I am the Huns overseas.

KALALEA: Huns… a slur some people used to call Germans.

[MUSIC: “Trench Blues”]

People like BC Franklin and W.E.B. Dubois thought maybe the war was an opportunity to earn the respect and dignity they so long deserved. That this fight would be empowering for African-Americans.

But there was also this growing concern among white people that Black soldiers sent to war might feel too empowered.

Adriane: I often quote James K Vardaman, who's just sort of a poetically hideous Senator from Mississippi, who says at one point, look, so, if we like put a gun in a Black man’s hands, and I think he says ‘inflate his untutored soul with military airs,’ it’s a short step to him thinking that he should, like, give his life for democracy elsewhere at home in Mississippi… He’s not wrong about that.

KALALEA: Vardaman would not get his way. Black men all over the country signed up and shipped out… knowing full well the segregated, violent reality that their families would have to endure. Soldiers boarded trains in Oklahoma City and waved banners out the windows saying: DO NOT LYNCH OUR RELATIVES WHILE WE ARE GONE.

Adriane: “And the horrible thing is you can hang up those banners, but that request would not be honored.”

[pause/music]

KALALEA: And those African-American soldiers who went overseas… discovered that Jim Crow had followed them there.

Adriane: I think it’s important to keep in mind that for African-American soldiers, those experiences are fused.

KALALEA: Professor Lentz-Smith told me about a man named Rayford Logan. He was a Black officer who would later become a historian.

Adriane: Rayford Logan wrote about his wartime experience that he fought two wars at once, his own and Woodrow Wilson’s. And he never figured out which one did more damage to him.

KALALEA: Of the 380,000 African-Americans soldiers who served, only about 40,000 saw combat. They were barred from most roles in the Navy and the Coast Guard, and banned from the marines altogether. Instead, they were relegated to unloading supplies, cleaning the bathrooms, and other grunt work.

And then there was the actual warfare itself.

You might be picturing scenes from the movies. Men caked in mud and blood, navigating chaos while crawling through explosions of earth and limbs. All that was true. But Black soldiers had to contend with even more.

Adriane: They find themselves in positions where they're constantly discovering that white soldiers who should be working with them, right, who should be their partners are far more invested in making sure that they understand their place than they are in having Black soldiers add to that collective effort. And so you get all of these accounts of fights that break out between white soldiers and Black soldiers. You have rumors of lynchings. You certainly have unfair arrests or court marshals, and then executions without enough notice that they're happening. Right? You have all of the kinds of nasty injustice that you would see in the US also happening within the American army.

[BEAT/MUSIC]

KALALEA: At the same time, for Black men and families back in the United States, the violence against them intensified. The lynchings continued, but the targets for attacks grew in scale… sometimes white mobs destroyed entire neighborhoods.

Many Black Americans were tired of living in fear and felt they had no choice but to leave the South. And so millions began moving to towns and major cities in hopes of finding work and living in peace.

But they were often not welcome. To their new white neighbors, the arrival seemed to threaten their jobs, their livelihoods, their communities... their White version of the American dream. And they responded with segregation, hatred, and in many cases, outright violence.

Minkah Makalani: Oftentimes, when I’m lecturing about this, I have to talk very slowly because I’m trying to not break into tears, that’s how bad it is.

KALALEA: Minkah Makalani is a historian at the University of Texas Austin.

Minkah: Just to give one sense of how systematic they were with the violence is that they would start fires in the back of homes and then shoot people as they came out of the front door. And that’s probably the least graphic description that I can give you of some of the things that they did in East St Louis.

KALALEA: East St. Louis, Illinois. July 1917.

Over three days, whites ravaged a Black neighborhood in the city -- looting, assaulting, and killing people in horrific ways.

Estimates vary, but it’s believed they murdered over 100… and maybe as many as 250 African-Americans. And some six thousand people fled the city. East St. Louis, like Greenwood in Tulsa, had been a community on the rise.

The attack shocked the country. Ida B. Wells traveled there -- to East St. Louis -- to report on it, as did DuBois. A Congressional committee investigated the incident and called out corrupt local officials and the savagery of the white mob.

In New York City, the NAACP organized a silent massive protest -- 10,000 people came out. I found a newsreel of the event. These silent, grainy films of women in white, men in black, walking in straight rows. They’re holding signs that say “Treat Us So That We May Love Our Country.” Children, who are leading the procession, carry a banner that reads “Mother, do lynchers go to heaven?”

And yet, the lynchings and attacks kept happening across the country.

Remember the newspaper publisher in Greenwood, AJ Smitherman? He wrote a telegram to the Governor of Oklahoma denouncing an attack on a small town about 50 miles north of Tulsa… called Dewey.

SMITHERMAN (Actor): “Dear Governor: Sunday night, August 11, in Dewey, Oklahoma, the homes of 21 Colored American citizens were destroyed by incendiary flames in the hands of a mob and the Colored inhabitants of that town driven out by the same mob.

At this time of our national crisis, while our Black boys, alongside of our white boys, are fighting, bleeding and dying on the shell-plowed battle fields of France for the principles of democracy, surely we will not desecrate the cause for which they are giving their life blood by permitting the mob rule, which is worse than Kaiserism, to steal from us here at home all the essence of a true democracy.

KALALEA: The governor responded to the telegram, and launched an investigation. But Smitherman also traveled to Dewey to report on the incident.

I called 3 different research centers to ask if they had the issue of the newspaper with his investigation. I’d read about Smitherman’s article in a book. But none of the archives had that particular issue -- they said it was missing from the microfilm.

KalaLea (on phone): You don’t have actual newspaper archives, either?

Archivist: No

KALALEA: And what’s even more remarkable to me is that I learned this sort of thing is pretty widespread. Accounts of racially motivated attacks literally snipped out of archives in libraries, universities, and other collections. Like so many other stories about this period, we’re just left with a gap in the record.

But we do know that Smitherman’s work brought visibility to what happened in Dewey, Oklahoma -- and it led to something pretty incredible at the time: the arrest of 36 members of the mob. Including the mayor.

Not everyone was as connected or powerful as Smitherman was. And efforts like his, would not be enough. Around the end of the war, Klan membership exploded -- to around 100,000 members. And in 1919, whites lynched around 80 people in the US. 13 of them were African American veterans.

The months of April to November of 1919 were so bloody that the poet James Weldon Johnson of the NAACP named it “the Red Summer”.

JOHNSON (Actor): I knew it to be true, but it was almost an impossibility for me to realize as a truth that men and women of my race were being mobbed, chased, dragged from street cars, beaten and killed within the shadow of the dome of the Capitol, at the very front door of the White House.

KALALEA: Johnson had been watching a four-day riot in Washington DC.

Historians sometimes use the word “pogrom” to describe what happened in so many cities in the summer of 1919.

TIMELINE

[read by different voices]

April 13th: A white mob burns a Black church in Jenkins County, Georgia, and congregants try to escape.. At least four people are killed...

May 10th: A group of white sailors attack a Black man who allegedly did not step off the sidewalk for them in Charleston...

May 15th: A Black man named Lloyd Clay is pulled out of jail, lynched and burned…

...a 72-year old Black man named Barry Washington is lynched by a mob...

...attack and burn a courthouse, lynch a Black man named Will Brown, and burn his body…

...attempts to lynch a man named Rob Ashley…

...A riot follows, a Black man is murdered…

...and beat any Black person they see, using bricks…

Local law enforcement in Bisbee, Arizona, plan an attack…

A homecoming celebration for African-American veterans is attacked…

...a series of attacks between white and black sailors...

Three Black churches and 1 community building is burned…

They shoot him over 1,000 times…

Eugene Williams is stoned to death by a group of white…

...Syracuse, New York, turns into a race riot...

...a lynching mob of 300 attacks…

...a riot is quelled in Baltimore Maryland...

… rounded up 200 African-Americans...

… Between 100 and 250 Black residents of Elaine, Arkansas are killed by a white supremacist vigilantes and federal troops.

[TIMELINE ENDS]

KALALEA: If you’ve ever lost a loved one, or someone special… you’re aware of the hurt and pain that comes with death -- especially unexpected death. So just for a minute, imagine the people whose lives were irreversibly impacted by all the violence and hatred in 1919. And this list reflects only a small selection of the killings that made it in the news. There were more, hundreds more that were never reported. Never even investigated.

And every death causes a ripple effect -- the people who suffer the loss of their husbands, mothers, children, neighbors… not to mention the physical and psychological wounds… trauma from which some do not recover.

And then to be told: there will be no funeral, no justice, no therapy. Deal with it. Or get out.

[pause/beat]

Minkah: If we must die, let it not be like hogs,

Hunted and penned in an inglorious spot,

While round us bark the mad and hungry dogs,

Making their mock at our accursèd lot.

KALALEA: The Summer of 1919 made it clear that the violence wasn’t going to end. Not without a fight. And so, a quiet conversation began to get louder...

Minkah: If we must die, O let us nobly die,

So that our precious blood may not be shed

In vain; then even the monsters we defy

Shall be constrained to honor us though dead!

This is Professor Makalani reading a poem by Claude McKay -- it’s called “If We Must Die.”

Minkah: O kinsmen! We must meet the common foe!

Though far outnumbered let us show us brave,

And for their thousand blows deal one death-blow!

What though before us lies the open grave?

Like men we’ll face the murderous, cowardly pack,

Pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back!

Minkah: This is a really defiant poem. And it’s one that’s really critical of the nature of White America at this time. And he’s calling the White world that is engaging in this, cowardly, he’s saying they aren’t men. But it is kind of reflective of the sentiment of the period. This defiance, this refusal to merely accept racial violence, but also a refusal to accept the society that says this kind of violence is appropriate if you don’t follow the protocols that we’ve laid out.

KALALEA: The poet Claude McKay was a member of a group based in Harlem -- a socialist group that called for African Americans to defend themselves with arms. They called themselves The African Blood Brotherhood. Like many similar groups at the time, they operated as a secret society for years -- but around 1919, they took their message worldwide.

Minkah: And people understand that you have to meet that violence with a certain level of violence as well.

KALALEA: That’s ahead. This is Blindspot.

[MIDROLL BREAK]

KALALEA: This is Blindspot: Tulsa Burning. I’m KalaLea.

Throughout the early 1900s, white-on-Black violence wasn’t limited to physical attacks. It touched every aspect of African American lives. From where they could go to how they got there.

Minkah: There are certain ways that as a black person, you are to act around white people, you know, so stepping off of a paved sidewalk, um, averting your eyes, particularly if you're a man and you're encountering a white woman.

KALALEA: Again, this is Minkah Makalani of the University of Texas at Austin.

Minkah: And that kind of structured people's daily activities. They did not want to do something that was going to incur the attention unnecessarily of Whites and definitely they always understood the possibility of violence.

KALALEA: That was also the experience of Black men serving in the military. They were often abused or mistreated by their fellow soldiers and forced to do the most menial tasks.

But when they were off-duty and had the chance to go beyond the strict limitations of the army, when they actually got to experience a bit of daily life in Europe… They found it illuminating… refreshing, even.

Adriane: It was an opportunity to step outside of the American system... They could look back at it and say Oh my God, it’s not as, like, natural as breathing that the world should happen this way.

KALALEA: Adriane Lentz-Smith of Duke University.

Adriane: Going to France and being somewhere where, like, you know, a white woman would give up her seat for a black soldier on the Metro makes you think, Oh, this is how things are… It sort of takes away the universality of it.

KALALEA: The French government even awarded the 369th infantry regiment -- the legendary Harlem Hellfighters -- with special medals for bravery.

And so, the soldiers returned from the war with a very real sense of how things could and should be.

In Black publications across the country, there were more calls to fight against the violence and oppression at home. DuBois wrote a powerful essay called “Returning Soldiers” --

Adriane: ...where he basically gives that clarion call for the militancy that Black folks will need to fuel this freedom struggle, where he says, you know, we return to a country that lynches and degrades and abuses us.

We return from fighting, we return fighting. And then he says -- make way for democracy. We saved it in France, and by the great Jehovah we will save it in the United States or know the reason why. Which --

KalaLea: Yeah, that’s it.

Adriane: That captures it. It still gives me chills. It is a beautiful piece of political writing.

KalaLea: I read it not too long ago and I felt the same -- like, wow.

Kimberly Ellis: When I was doing research on literally what was happening in the early 20th century, I wanted to know what was the spirit, you know, that was being swept across the nation.

KALALEA: Kimberly Ellis is a scholar of American and Africana studies.

Kimberly: I found out about this group called the African Blood Brotherhood and they were just so fierce.

KALALEA: Now there were several Black liberation organizations taking shape at that time, including the Universal Negro Improvement Association, or UNIA, founded by Marcus Garvey.

The African Blood Brotherhood was founded by Cyril Briggs, an African Caribbean American writer and self-proclaimed communist based in Harlem. The ABB was small, but influential -- in part thanks to its magazine, The Crusader.

Kimberly: They spoke unapologetically about their blackness, about armed self-defense. I admired the fact that The Crusader, they refused to take ad money for, basically, skin bleaching… they refused to take ad money for that. And I thought that was so progressive! I was definitely impressed.

KALALEA: The Crusader also featured ads and images of dark-skinned women, with a frequency which was uncommon at the time. And in it, there were these recipes for making the most of your stale bread and also dress patterns for fuller-figured women.

It’s hard to know exactly how many active members the ABB had by 1920, probably around one to two thousand. And as many as two thirds of them were women.

University of Texas Professor Minkah Makalani:

Minkah: Elsewhere within The Crusader, they’re actually talking about the problem of infant mortality, the problem of child sickness, the problem of sanitation in tenements in Harlem. They’re addressing these concerns that speak to those daily preoccupations that tended to fall on women in the household.

KALALEA: The magazine urged its readers to take up arms against lynch mobs and protect people of African descent all around the world. The ABB was sort of like a 1920’s version of the Black Panthers.

The membership included many veterans, among them... Harry Haywood, who would become a leading figure in the Communist Party.

Minkah: My guess is that, in Chicago, when Harry Haywood is talking about arming themselves and taking up positions on rooftops to defend the community... My guess, based on the gender dynamics of that time, is that they wouldn’t have wanted women to go on rooftops and do that kind of thing. But I would not be surprised if we found out that black women in the organization are at least armed to protect their families as they’re trying to escape the violence.

KalaLea: Where are they getting these weapons? Can you go into a little detail about that?

Minkah: Well, so I think the thing to remember, and you know, this is kind of a problem with the mythology about the civil rights movement being this passive movement… Black people in the South, this was a gun culture. So people had guns, they were armed. With the return of people from the War, people who are veterans, that they brought some of them bring their arms back with them.

Just to give an example of how this might have functioned, in Louisiana, Queen Mother Moore, Audley Moore --

KALALEA: … a prominent black nationalist and a civil rights leader...

Minkah: ...she gives this account of a meeting at a Longshoremen’s Union meeting hall where they had invited Marcus Garvey to come give a lecture. And the local sheriff said, if he gives an address we’re going to arrest him.

KALALEA: So, the organizers of the lecture gather up all of their guns, put them in burlap sacks... and bring them to the meeting hall.

Minkah: Marcus Garvey goes to give his speech, the sheriff and his deputies begin to make their move and everybody pulls out their guns. He’s going to speak and you’re not going to touch him.

And so that’s, I think, the same kind of sensibility around defending themselves and the need to defend themselves, to express themselves politically that would have been going on in Tulsa at this time.

I just don’t think anyone at that moment could have anticipated the degree to which that violence, how extensive it would be. They probably just had no frame of reference for what was coming.

KALALEA: After the Red Summer of 1919, the African Blood Brotherhood started establishing what it called command posts all across the country. Soon it had members everywhere --

Minkah: … in Louisiana, in the Dominican Republic and Dominica and Chicago.

KALALEA: And in 1921, just a couple months before the massacre, they set up a post in Tulsa.

In the days following the massacre, local law enforcement was quick to blame the African Blood Brotherhood. They claimed the group incited a rebellion that caused all the damage in Greenwood.

It’s not even clear that they were involved in the confrontation outside the city’s courthouse. But they represented a commitment to self-defense that was starting to gain more widespread traction. And even AJ Smitherman -- the publisher of The Tulsa Star -- was urging his readers to defend themselves:

SMITHERMAN (Actor): ….No man should arm himself except for the purpose of self-protection or to uphold the majesty of the law and when he is thus armed, no officers has any right to divest him of his arms and he is a coward who would surrender his arms under such circumstances, regardless of the number against him.

The Tulsa Star is unalterably opposed to mob violence, regardless of the color of the men composing the mob, and while we recognize the old adage that "the pen is mightier than the sword," we have had some actual experience with the cowards who compose mobs, which has convinced us that two or three determined men armed for the occasion can thwart the purpose of any mob if they act in earnest and in time.

Kimberly Ellis: Across the nation, Black men and women were standing up for themselves. And this tradition comes from the American South, you know, literally us having to fight the KKK, the white supremacists, and then moving into the West… It’s all related. It all matters.

KALALEA: And that made many white people really worried. They began talking about ways to “clean up” Black areas of “their” city so they could get rid of what scared them. They didn’t see Greenwood the way we do today -- as a prosperous, thriving community, a rare marvel.

After the massacre, white-run newspapers published justifications for the attack. Like this one in the Tulsa Tribune:

REPORTER (Actor): Such a district as the old N-Town must never be allowed in Tulsa again. It was a cesspool of iniquity and corruption. The public would now like to know: Why were these n----s not made to feel the force of the law and made to respect the law?

KALALEA: Which brings us to May 30, 1921 -- the day a young African-American shoe-shiner named Dick Rowland got onto an elevator operated by Sarah Page, a young white woman. What happened in the elevator is up for debate. The details don’t seem to matter. Greenwood’s fate... was sealed.

And here’s another detail lost from the historical archives: that on the day of Rowland’s arrest, the white-owned Tulsa Tribune ran an article with the headline, “To Lynch A Negro Tonight.” It’s missing from every record of that day’s paper. Like, cut out. But we know about it because witnesses have described it.

Kimberly Ellis: In Tulsa, when they found out that Dick Rowland had been arrested, Andrew Smitherman would be one of the first persons to know, so Andrew Smitherman and his colleagues, they had heard this before. This is exactly like what they had experienced in other towns before they arrived to Tulsa. There’s a black teenager, there’s a black youth down at the courthouse, and the whites are gathering. And so fellas, it’s time for us to go down there and get armed to prevent him from being lynched.

KALALEA: When they got there, they spoke to the sheriff -- go home, he told them. he didn’t need help protecting Rowland. He’d personally keep him safe.

But the growing crowd of White people outside the courthouse suggested otherwise. They were screaming threats and getting more agitated with each passing minute. Smitherman and the others knew what could happen next.

Call it what you like… a race war, a riot, a massacre. But it had begun.

That’s next time, on Blindspot.

[THEME MUSIC]

Blindspot: Tulsa Burning is a co-production of The History Channel and WNYC Studios, in collaboration with KOSU and Focus Black Oklahoma. Our team includes Caroline Lester, Alana Casanova-Burgess, Joe Plourde, Emily Mann, Jenny Lawton, Emily Botein, Quraysh Ali Lansana, Bracken Klar, Rachel Hubbard, Anakwa Dwamena, Jami Floyd, and Cheryl Devall. The music is by Hannis Brown, Am’re Ford, Isaac Jones, and Chad Taylor.

The song "Trench Blues" was written and performed by John Bray.

Our executive producers at The History Channel are Eli Lehrer and Jessie Katz. Raven Majia Williams is a consulting producer. Special thanks to Herb Boyd, Kelly Gillespie, Shelley Miller, Jodi-Ann Malarbe, Jennifer Lazo, Andrew Golis, Celia Muller, and Andy Lanset.

Andre Holland was the voice of B.C. Franklin; and Maurice Jones was A.J. Smitherman. You also heard the voices of: Terrance McKnight, Dar es Salam Riser, Javana Mundy, John Biewen, Jack Fowler, Tangina Stone, Emani Johnston, Danny Wolohan, and Jay Allison.

I’m KalaLea, as always -- thanks for listening.

###