Why is Trump’s Campaign Suing a Small Wisconsin TV Station?

( Priorities USA/YouTube )

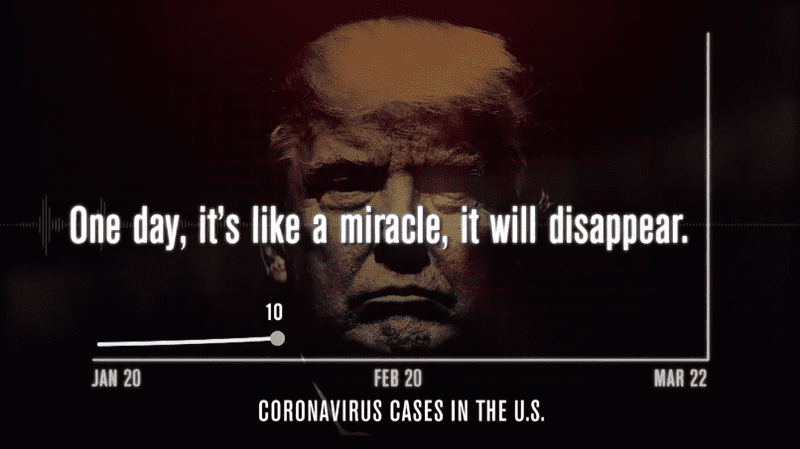

ANDREA BERNSTEIN: In March, a super PAC placed an an anti-Trump advertisement on local TV stations in battleground states.

[THE AD PLAYS SEVERAL CLIPS OF TRUMP, INTERSPERSED]

PRESIDENT TRUMP: The coronavirus …

PRESIDENT TRUMP: This is the new hoax …

PRESIDENT TRUMP: We have it totally under control.

[FADE UNDER]

BERNSTEIN: There’s a visual on the screen — a line counting COVID-19 infections ticks up and up.

[A CLOCK TICKS FASTER AND FASTER]

PRESIDENT TRUMP: [FADES UP] … we’ve done a really great job at keeping it down to a minimum … [FADES DOWN]

BERNSTEIN: Clips of the President dismissing the virus play in the background.

AD VOICEOVER: Priorities USA Action is responsible for the contents of this ad.

BERNSTEIN: Priorities USA is a type of super PAC. It supports Joe Biden. It can collect unlimited contributions from almost any source for expenditures, independent of the Biden campaign.

The day after the advertisement first aired, the Trump campaign sent cease and desist letters to TV stations. The campaign says it sent these letters to stations that aired the ad in Florida, Michigan, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

In the letter, the campaign claimed the ad was "deliberately false and misleading” because it featured clips taken from different contexts, spliced together in a way the campaign considered deceptive.

"Should you fail to immediately cease broadcasting P.U.S.A.’s ad," the letter reads, "Donald J. Trump for President, Inc., will have no choice but to pursue all legal remedies available.”

A spokesperson for Priorities USA told us that none of the 72 stations that ran the ad pulled it from the air.

[A MOMENT OF MUSIC]

Then, a few weeks later, the Trump campaign did something that — as far as we can tell — no other presidential campaign has ever done: It filed a defamation suit over the ad. The campaign didn't sue the super PAC, it sued just one of the local stations.

WJFW. A small NBC affiliate in northern Wisconsin.

[STATION INTRO PLAYS]

WJFW BROADCASTER JUSTIN BETTI: Welcome to Newswatch 12 at Five. I’m Justin Betti. Today, President Trump's campaign team has sued WJFW, our TV station, over a political ad, which you may have seen. That ad, by the Democratic-friendly super PAC … [FADES UNDER]

[TRUMP, INC. THEME PLAYS]

BERNSTEIN: Hello, and welcome to Trump, Inc., a podcast from WNYC and ProPublica that digs deep into the business of Trump. I'm Andrea Bernstein.

Donald Trump has always been litigious. Now he's found a novel way to file lawsuits, with a seemingly endless stream of money behind them.

Today on the show: How the President's longtime tactic of taking his critics to court has been picked up by his reelection campaign — a group with hundreds of millions of dollars to spend on his behalf.

The Wisconsin lawsuit is part of record-breaking legal spending by a presidential campaign. Disclosures show the campaign has raised over $342 million, and spent $16.8 million on legal services alone. And this is just the campaign — not associated committees.

The legal spending is more than any past presidential campaign, and more than 10 times what Joe Biden's campaign has spent on legal services.

In February of 2020, President Trump's reelection campaign began filing a series of defamation suits against news outlets.

REPORTER: [OFF-MIC] Your campaign today sued The New York Times for an opinion.

PRESIDENT TRUMP: Yeah.

REPORTER: [OFF-MIC] Is it your opinion, or is it your contention that if people have an opinion contrary to yours then they should be sued?

PRESIDENT TRUMP: [OVER CAMERAS CLICKING] Well, when they get the opinion totally wrong, as The New York Times did — and, frankly, they've gotten a lot wrong over the last number of years … So we'll see how that — let that work its way through the courts.

BERNSTEIN: The first three lawsuits were filed in rapid succession against The New York Times, The Washington Post, and CNN. The suits claimed that opinion pieces linking the Trump campaign to Russia were false and defamatory.

In its filings against The New York Times and The Washington Post, the campaign alleges, quote, "a systematic pattern of bias against the campaign." The lawsuit claims the publications are "extremely biased" against Republicans in general.

The campaign also sued CNN over an opinion piece that it published after President Trump gave an interview to ABC News' George Stephanopoulos.

GEORGE STEPHANOPOULOS: If Russia — if China — if someone else offers you information on an opponent, should they accept it or should they call the FBI?

PRESIDENT TRUMP: [AFTER A PAUSE] I think maybe you do both. I think you might wanna listen. I don’t — there’s nothing wrong with listening. If somebody called [PAUSE] from a country — Norway — “We have information on your opponent.” Oh! I think I'd wanna hear it.

GEORGE STEPHANOPOULOS: You want that kind of interference in our elections?

PRESIDENT TRUMP: It's not an interference. They have information. I think I'd take it.

BERNSTEIN: The opinion piece that came after was written by Larry Noble, a CNN contributor and former General Counsel to the Federal Election Commission. In it, he commented, "The Trump campaign assessed the potential risks and benefits of again seeking Russia's help in 2020 and has decided to leave that option on the table."

Lawyers for the Trump campaign argue Noble's article was defamatory. In a filing, they say that Trump's interview with Stephanopoulos isn't relevant and that President Trump was talking about Norway, not Russia. They call his comments about being willing to accept foreign assistance "relatively innocuous."

Lawyers for the Times, The Washington Post, and CNN are asking courts to dismiss the complaints. First Amendment lawyers we spoke with said it’s very difficult to win a defamation case if you're a public figure, like the President.

After the initial three suits against the Times, the Post, and CNN, the campaign filed its fourth defamation lawsuit — the one against that TV station in Wisconsin.

On April 13th, President Trump's reelection campaign sued Northland Television LLC, which owns WJFW.

[A MOMENT OF MUSIC]

BERNSTEIN: Trump, Inc. reporters Katherine Sullivan and Meg Cramer wanted to understand all of the campaign's spending on legal services and how it fits into the nexus of the Trump campaign, the White House, and the business of Trump.

Meg and Katherine examined spending by the Trump campaign and four affiliated committees, talked to lawyers and campaign finance experts, and read through hundreds of pages of lawsuits.

Their story starts with a seemingly straightforward question:

MEG CRAMER: Why did the Trump campaign file a lawsuit against a small TV station in northern Wisconsin?

BERNSTEIN: Meg Cramer takes it from here.

CRAMER: So, we asked the campaign and their lawyers, and they didn't get back to us.

And when I reached out to WJFW, a lawyer for the station told me they weren't talking to the press about the lawsuit or anything else. So, I called a reporter who lives in the area.

BEN MEYER: And I am recording audio on my end as well.

CRAMER: Amazing!

CRAMER: A radio reporter.

MEYER: Sure, I can introduce myself. My name is Ben Meyer, and I am a special topics correspondent at WXPR Public Radio, here in Rhinelander, Wisconsin.

[A FOLKSY, UP-TEMPO SONG FEATURING THE NAME “RHINELANDER” IN THE LYRICS PLAYS]

CRAMER: Rhinelander is a city in Oneida County in way-northern Wisconsin. Population about 8000.

Ben grew up in southern Wisconsin, where the landscape is rolling hills and open farmland. Northern Wisconsin is a bit more wild. He told me when his mom visits, she feels claustrophobic — like she can't get out of the trees.

Ben's been a local journalist in the area for about a decade. He covers water resources: things like water quality and mining pollution.

MEYER: The counties where I do most of my work have some of the highest concentration of freshwater lakes in the world. Oneida County alone has a thousand lakes — more than a thousand lakes.

[DRIVING ACOUSTIC MUSIC PLAYS IN]

CRAMER: Before making the jump to radio, Ben worked at a different local news outlet in Rhinelander: the TV station, WJFW.

MEYER: I started as a reporter and producer. Um, I wore a lot of hats along the way. I was, um, uh — I was an executive producer at one point. I think they gave me the title of “Managing Editor.” At one point I was the Interim News Director for a couple of weeks. I loved working there. I loved my coworkers and I loved doing stories about, and with, and for my neighbors.

LTSI

CRAMER: Ben knows a ton about the history of the station. He used to give tours —

MEYER: Okay, so the first thing I would point out is WJFW's really unorthodox history.

CRAMER: It was founded by a local congressman while he was still in office.

MEYER: And he founded it in 1966. A little building under a big tower.

CRAMER: Two years later, a small plane flew into the tower, knocking it down onto the building. The three passengers on board died in the accident. Next stop, master control.

MEYER: We say, “Okay, someone sits here 24 hours a day to make sure the commercials are on at the right time, and make sure that the …” [MEYER FADES UNDER]

CRAMER: Past the newsroom, and into the studio.

MEYER: The set is awesome. The set looks great.

CRAMER: Picture a lot of warm wood paneling.

MEYER: You pan away from the set, there’s, like, an old couch over there and a couple of old chairs over there, y’know — an exposed rafter up here or whatever, but it's fine! Like, it looks great on TV, so that's all that matters.

CRAMER: And then what's the next stop on the tour?

MEYER: Okay. Um, the next stop is … That's it! Because it's not a big station. Like, it's a — it’s a small-market TV station, right?

LTSI

CRAMER: So you worked there for eight years?

MEYER: Between seven and eight. Uh, seven and a half, I think.

CRAMER: When the Trump campaign sued the station, Ben noticed.

MEYER: Um, the first thing that went through my head is, um, “Wow! People are going to start hearing the name Rhinelander because of this Trump campaign action — a lot of people that have probably never heard the name Rhinelander, Wisconsin, before.” That's the first thing that went through my head.

[A BEAT, THEN A TRANSITION TO A BROADCAST FROM WJFW]

WJFW NEWSCASTER: Our station neither endorses nor opposes this ad. Nor any other … [FADES UNDER]

CRAMER: The day the lawsuit was filed, WJFW led with the story in their five o’clock newscast.

WJFW NEWSCASTER: That ad continues to be aired on many TV stations across the country. However, WJFW is the only station named in the suit, and that suit still has not been served. We have only heard about it and read about it through other news sites and on the President's campaign website. In other news, many people are looking forward to the day when they can just go outside and go to their favorite events again, but organizers for several local events … [FADE UNDER]

[SLOW ACOUSTIC MUSIC PLAYS]

CRAMER: Before we go any further, I think it's important to mention that none of the legal experts I talked to for this story thought the campaign's lawsuit against WJFW had any merit.

Matt Sanderson, who served as counsel for Senators John McCain and Mitt Romney, told me he thinks the Trump campaign is "engaging in scare tactics." He said, "As a longtime Republican and someone who's worked in the trenches for many, many Republican candidates, I'm appalled to see a Republican president suppressing speech.”

Another experienced Republican election lawyer — who didn't want to be named because they still work in the space — said they thought, quote, "most election lawyers would not be able to file this without their skin crawling."

We asked Husch Blackwell, the firm representing the Trump campaign, if they thought the lawsuit against WJFW would be successful. We did not hear back.

[A LONG MOMENT FOR MUSIC]

CRAMER: By filing its lawsuit in Wisconsin, the Trump campaign picks up a possible advantage.

Some states have what are known as Anti-SLAPP laws. SLAPP — S-L-A-P-P — stands for “Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation.”

And anti-SLAPP laws make it harder, and more expensive, to file frivolous defamation lawsuits. For example: If a court decides that a defamation suit has no merit, anti-SLAPP laws might require the person who filed the suit to cover the defendants' legal expenses.

Florida, one of the states where the ad aired, has an anti-SLAPP law on the books. Wisconsin does not.

WJFW was not the only station in Wisconsin that ran the Priorities USA ad. But Ben noticed that it was the only station in Wisconsin that got sued.

MEYER: Um, then what went through my head is, “Okay. Why?” I’m like, “Why — why not a station in La Crosse, Wisconsin, or Eau Claire, Wisconsin? Or anywhere else in Wisconsin, or any other small-market station that has aired this ad in the United States?”

CRAMER: Ben didn't know. He still doesn't. But he has some educated guesses.

MEYER: And my speculation was that, “Okay. WJFW might be a little different than those other small market stations because WJFW has a really small ownership group.”

CRAMER: That group, Rockfleet Broadcasting, owns just three stations. This NBC affiliate in Rhinelander, Wisconsin, and two stations that share a studio in Bangor, Maine.

MEYER: Yeah, it's possible in my mind — and, again, speculation — that the Trump campaign saw a — a station with a small ownership group as — as kind of an easy target, a group that they could bully around a little bit more than a station that fell under the umbrella of a big ownership group.

[MUSIC QUIETS]

CRAMER: Ben noticed something else about the lawsuit. Initially, the campaign filed it in Price County. WJFW is headquartered in Oneida County.

MEYER: Price County is immediately to our West. It's smaller. Its population is fewer than 20,000. And this entire area — the entire Northwoods — in the 2016 election was red. All counties voted for Trump. They voted for Trump to different degrees, as you can imagine, though. Trump won Price County by about 25 points.

CRAMER: A higher margin than in Oneida County.

MEYER: So, when I was asking the question that you're asking in your head right now, “Well — well, if the station’s in Oneida County, why would they file it in Price County?” Maybe the campaign figured, “Alright. We'll file in Price County, which is still in WJFW's viewing area, and perhaps we'll get a little bit more sympathetic public. We might get a little more sympathetic judge. And that could help our case.”

[ACOUSTIC MUSIC COMES BACK UP]

BERNSTEIN: We know that Trump has done things like that before. To help us understand what's going on in Wisconsin in 2020, we looked back at a case filed in 2006 in New Jersey, against a journalist who wrote a book about Trump. Susan Seager is a media defense lawyer who teaches at The University of California, Irvine, School of Law.

SUSAN SEAGER: I first became interested in Trump when he filed a lawsuit against Tim O'Brien when Tim O'Brien said he wasn't a billionaire.

BERNSTEIN: O'Brien was writing about business for The New York Times in those days, and he had written a book about Trump that showed he was a hundred-millionaire, not a billionaire. Trump sued for defamation, seeking $5 billion in damages.

SEAGER: I didn't really know Trump that much. I just knew he was a celebrity. So I follow that case, and I knew he would lose, and he did lose.

BERNSTEIN: It was a high-profile case that displayed a lot of the characteristics of Trump's litigation strategy, including that Trump didn't file it in Manhattan, which is where the publisher and the Trump Organization are headquartered, but in South Jersey, where one Trump political ally had a hand in appointing judges. In the lawsuit, there were thousands of pages of motions filed, depositions were taken, there were high-priced lawyers on both sides. If you're a First Amendment specialist, it's a hard case to forget.

SEAGER: And then it was sort of bubbling around in the back of my mind. And then when he was running for president, and there were stories about all the lawsuits that he was a part of — both as a defendant and a plaintiff — I started researching other lawsuits, um, involving Trump, and I was shocked to see so many.

BERNSTEIN: USA Today reported in 2016 that Trump had been involved in at least 3,500 lawsuits.

CRAMER: Seager started keeping track of the cases where Trump sued for defamation or tried to bring his critics to court. She keeps a set of manila folders with the cases from before Trump became president. This year, she started a new set of folders, and added the four defamation suits filed by the campaign.

I asked Susan Seager the same thing I asked Ben: Why, out of all stations that aired the ad, did the campaign end up suing WJFW?

SEAGER: I do think that maybe they thought they'd go after someone small. But what their real goal was — what his real goal is — is to stop all TV stations from running these ads.

CRAMER: It’s not just that the Trump campaign sued a small station that's less likely to have the legal resources to fight a defamation suit. It's that they sent a signal to other stations like WJFW: we are willing to sue.

We don't know whether or not this lawsuit will discourage other stations from running political ads that are critical of the President. A spokesperson for Priorities USA told us they haven't had any trouble placing ads since the campaign sued WJFW.

[LIGHT PIANO MUSIC PLAYS]

CRAMER: Seager estimates that fighting a defamation lawsuit brought by a high-profile group like a presidential campaign could cost anywhere between $100,000 to $250,000, just to go through the process of getting it dismissed.

SEAGER: If you can't get it dismissed at the very beginning, then there's depositions, there's exchange of documents, and that could be $500,000 or even a million dollars.

CRAMER: Publishers often have liability insurance —

SEAGER: Sometimes they have a big deductible, though. Uh, sometimes the policy limit may not be the same as what your legal fees are.

BERNSTEIN: In this case, WJFW's owners did decide to fight the lawsuit, and they brought in an experienced legal team.

We asked WJFW's owners how much they expect it's going to cost to defend the case, and whether or not the station has insurance. They declined to say, citing confidentiality.

The station commented, through a lawyer, that "WJFW has no choice but to fight the Trump campaign's attempt to bully a small-market broadcaster into surrendering its First Amendment rights. The public counts on local broadcasters, especially in an election year, to remain free to air criticisms of public officials."

After the case was initially filed, lawyers for the station filed papers to move the case to federal court. And it was moved to federal court. The station's lawyers also asked the court to dismiss the complaint. That's still pending.

Priorities USA, the super PAC that paid for the ad, joined the case as a defendant. Their lawyers have also asked the court to dismiss.

We asked the Trump campaign and its lawyers why they chose to sue WJFW, why they filed their case in Price County, and if their lawsuit was intended to deter stations from accepting advertising like this in the future. They did not respond.

We'll be right back.

[MIDROLL]

BERNSTEIN: We're back. And before we go on, I want to talk about something we've explored before on Trump, Inc. — how Trump's fundraising success is due in part to his openness to taking requests from people who give him money. We did a whole episode on this earlier this year. Here's an excerpt of that, from my co-host Ilya Marritz.

[CLIP FROM TRUMP, INC. EPISODE “AN INTIMATE DINNER WITH PRESIDENT TRUMP” STARTS]

[THE SOUNDS OF CHITCHAT AT A DINNER PLAY]

ILYA MARRITZ: April 30, 2018. It's a small gathering in a private dining room in the Trump International Hotel in Washington.

VOICE: Some people may not want their pictures taken.

MARRITZ: It's a collection of mostly wealthy, well-connected people. They've pledged financial support for a group that's promoting Trump's re-election.

VOICE: Thank you everyone, once again. Mr. President, thank you for being here. [APPLAUSE]

MARRITZ: People take their seats. Drinks are poured. Dinner is served. The phone that's recording all of this must be pretty close to the President. Trump talks about what he wants to talk about. Golf, politics, the intersection of golf and politics.

PRESIDENT TRUMP: You know that Kim Jong Un is a great golfer? You know that, right? [CHATTER AND LAUGHTER]

MARRITZ: And a lot of the guests here want things from the President.

[LAUGHTER]

[CLIP FROM “AN INTIMATE DINNER WITH PRESIDENT TRUMP” ENDS]

BERNSTEIN: Throughout his presidency, Trump has made it clear he will favor people who give him money, or patronize his businesses.

The man who released this tape, Lev Parnas, was working on an energy deal in Ukraine. He was invited to this dinner after promising a six-figure donation.

So here we are. Trump and his affiliated committees have raised lots of money — record-breaking amounts — and they're using some of that money to fund a series of defamation lawsuits.

KATHERINE SULLIVAN: I'm here. Can you hear me?

CRAMER: Hello!

BERNSTEIN: We go back now to Meg Cramer and Katherine Sullivan.

SULLIVAN: [LAUGHINGLY] Hello from my childhood bedroom closet in Binghamton, New York. [CRAMER AND SULLIVAN LAUGH]

CRAMER: Katherine and I have been trying to figure out just how much money the Trump campaign and affiliated groups are spending on legal services.

SULLIVAN: So we looked at all the receipts for expenditures that were classified as either "legal consulting" or "legal and IT consulting" or "legal and compliance.”

CRAMER: We took these legal expenses and added them up for the RNC, the Trump campaign, and three other related committees. Those committees are America First Action, which is a super PAC that supports Trump and can raise unlimited amounts of money from donors, and two committees that raise money jointly for Trump and other Republicans.

SULLIVAN: So that's Trump Victory, Trump Make America Great Again Committee, and America First Action. And then, altogether, we found that all these entities have spent over $37 million on legal matters.

CRAMER: Comparable Democratic groups have spent less than half that in the same period since 2017.

[A QUIET MOMENT OF MUSIC]

CRAMER: So, more than $37 million across all these affiliated committees. Where is that money going?

One thing we know is that the campaign covered some of the legal expenses related to the Mueller probe. Also, the campaign has been named as a defendant in at least a dozen lawsuits, by plaintiffs ranging from employees who say they were discriminated against to protesters who say they were attacked at Trump rallies. The campaign has denied these allegations.

PRESIDENT TRUMP: I knew this would happen. I knew it was gonna happen. [FADES UNDER]

CRAMER: Trump actually complained about this at one of his coronavirus briefings in March.

PRESIDENT TRUMP: [FADES UP] When I ran, I said, "It's going to cost me a fortune." Not only in terms of actual costs — look at my legal costs! You people, everybody — everybody is suing me. I'm being sued by people that I never even heard of. I'm being sued all over the place — I’m doing very well, but it's unfair.

[LTSI]

CRAMER: To figure out what other kinds of legal work Trump's campaign is paying for, Katherine put together a list of around a hundred different entities doing legal consulting for the campaign and affiliated groups.

SULLIVAN: So some were really big corporate law firms — Jones Day, for example, was the highest-paid firm and they've made $13.3 million from the campaign and these committees.

CRAMER: Jones Day is where Trump's former White House Counsel Don McGahn works.

SULLIVAN: Then there are some smaller entities. For example, there's one owned by the former White House Ethics Counsel, Stefan Passantino. The campaign and the RNC have paid his company more than $400,000.

CRAMER: You can't exactly tell what kind of legal consulting these groups are doing.

SULLIVAN: I also looked up all the lawsuits that I could find in which the Trump campaign was a party, but it's not a perfect match to try and line up the cases with the payments to the law firms. A lot of the work that these firms are doing doesn't necessarily result in public-facing legal action. So they could be doing research, or consulting, or giving advice, or hiring opposition researchers.

CRAMER: So on one side you have this list of all these companies who've been paid for legal work by the campaign, and on the other, you have this list of cases and legal action that's a shorter list that the campaign is involved in.

SULLIVAN: Right, right.

CRAMER: And — and you can't necessarily match them up.

SULLIVAN: Right.

CRAMER: Taking a look at all these numbers, was there anything that caught your attention?

SULLIVAN: So I think the most surprising thing was that the second highest-paid entity on this list was a firm called Harder LLP.

CHARLES HARDER: Hulk Hogan filed two lawsuits today in Tampa, FLORIDA. [FADE UNDER]

SULLIVAN: This is Charles Harder. He's an attorney who specializes in high-profile reputation defense lawsuits. He’s the lawyer who represented wrestler Hulk Hogan against Gawker Media —

HARDER: It alleges that the defendant posted excerpts of the videotape at their website, gawker.com, for the purpose of … [FADE UNDER]

SULLIVAN: — in a case that was being secretly bankrolled by Peter Thiel, a tech billionaire who went on to become a big supporter of — and donor to — President Trump.

HARDER: Hulk Hogan will take all reasonable steps necessary to ensure that all persons and entities who are involved in this are punished to the fullest extent of the law.

SULLIVAN: Hogan, backed by Thiel, won the case. As a result of the lawsuit, Gawker went bankrupt.

We know that Harder started doing work for the Trump family in 2016 on lawsuits that Melania Trump filed against the British publication The Daily Mail. The Daily Mail ended up retracting their story, apologizing, and settling for a reported $2.9 million, according to the Associated Press.

CRAMER: We also know that Harder did defense work for Trump when Stormy Daniels claimed Trump defamed her. She lost.

SULLIVAN: It appears that a lot of Harder's work involves responding to unfavorable media stories about the President. He's threatened or taken legal action against author Michael Wolff, Mary Trump, Steve Bannon, and Omarosa Manigault Newman, plus news outlets like The New York Times and CNN. ABC reported that Harder recently sent a letter to Michael Cohen, demanding he halt writing a "tell-all book" about his work for Trump.

[MUSIC COMES UP]

CRAMER: In late July, Cohen filed a lawsuit against Attorney General Bill Barr and the Bureau of Prisons, claiming he was sent back to prison "in retaliation for doing a book about the President." The Justice Department has declined to comment.

The first Trump campaign payment to Harder's firm comes in January 2018. Since then, the campaign has paid his firm over $3 million. Just for some context, that's more than the Biden campaign has spent on legal services, total.

What do we know about the work that he's doing just for the campaign?

SULLIVAN: So, again, campaign finance laws don't require campaigns to disclose much detail about their spending. We know from legal filings that he defended the campaign in a wage discrimination claim brought by a former campaign staffer who says Trump forcibly kissed her. The White House denied this. The staffer, Alva Johnson, dropped her lawsuit after several months. She told The Daily Beast at the time, ”I'm fighting against a person with unlimited resources." She added, "That's a huge mountain to climb."

And then it's Harder that's representing the Trump campaign in three of the defamation lawsuits: the ones against The New York Times, The Washington Post, and CNN. But the Wisconsin case is being handled by a different law firm, Husch Blackwell. They've been paid around $200,000 by the campaign.

[LTSI]

BERNSTEIN: Trump, Inc. reporters Katherine Sullivan and Meg Cramer.

[A LONG PAUSE]

BERNSTEIN: For a campaign that's raised over $300 million, the money it costs to bring these cases is basically nothing. It's a situation where no lawsuit is too big or too small.

After losing his lawsuit against the journalist Tim O'Brien, Trump told The Washington Post that he knew he couldn't win, but he sued anyway. He said, "I spent a couple of bucks on legal fees, and they spent a whole lot more. I did it to make his life miserable, which I'm happy about.”

[OMINOUS MUSIC PLAYS]

BERNSTEIN: Trump doesn't have to stake any of his own money on the lawsuits against The New York Times, The Washington Post, CNN, and WJFW. His generous donors are picking up the tab.

[A LONG BEAT FOR MUSIC, WHICH TRANSITIONS TO FOLKSY, UPBEAT CREDITS MUSIC]

This episode was reported and produced by Meg Cramer and Katherine Sullivan. Our editor is Eric Umansky. Jared Paul does our sound design and original scoring. Hannis Brown wrote our theme and additional music.

Special thanks this week to Karl Evers-Hilstrom, Brendan Fischer, Eugene Volokh, Polly Irungu, and Sahar Baharloo.

Matt Collette is the executive producer of Trump, Inc. Emily Botein is the Vice President of Original Programming for WNYC, and Steve Engelberg is the Editor-in-Chief of ProPublica.

I'm Andrea Bernstein. Thank you for listening.

Copyright © 2020 ProPublica and New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.