The People vs. Dutch Boy Lead

The Secret History of Lead

Hey everybody. Welcome to our new show! Before we get started, a word about what we’re doing here, and really what you can expect from us….

We’re trying to make sense of the world, in a time when soooo much seems nonsensical. And we’re gonna come at that in every way can think... which means you’re gonna hear a LOT of different kinds of stories, from a LOT of different people.

But always, our goal is to understand the society we’ve built. To really, genuinely look at how we feed and clothe and house ourselves, and educate our kids and take care of our sick and how we have fun, how we make art, and all of that stuff…. It’s all the result of decisions we’ve made about the way we want to live together. So let’s name those choices and let’s ask, are we really ok with this?... And if not, how we can do it better...make it work for more people? That’s our driving question, and we hope you’ll join us in trying to answer it.

I’m Kai Wright. Welcome to The Stakes… In this episode: the little Dutch boy and Old Man Gloom.

***

WERTH: Kai Wright.

KAI: Christopher Werth.

WERTH: I have a question for you.

KAI: Shoot.

WERTH: When I say Dutch Boy, do you know who the like little Dutch Boy character is?

KAI: Like literally who he is?

WERTH: Well, could you describe him?

KAI: It’s like a little white baby, I think.

WERTH: It's not a white baby.

KAI: It's not? In my mind it's a little white baby.

WERTH: It's a little white kid. Blond hair blue overalls blue cap. He's wearing clogs.

KAI: That's a white baby.

WERTH: He's Dutch you know but he's not a baby. He's like you know he's 7 or 8 years old or something and he's always carrying around a bucket of paint and a paintbrush. So if you go to the hardware store now and you walk by a can of Dutch Boy paint you're going to see this little Dutch Boy character. It's just a little logo on the can of paint. But what I didn't know is that in the early part of the 20th century -- so like 20s 30s -- the company that made Dutch Boy paint, it was called the National Lead Company.

KAI: A lead company is making paint

WERTH: Yes. It made a very active decision to use this Dutch Boy character much more overtly to actually advertise to kids.

KAI: To sell the paint to kids?

WERTH: To advertise lead paint to kids as a way to get to their parents, which given what we know about lead paint today it sounds absolutely totally disastrous? I mean lead causes brain damage. It causes lower IQ. Hyperactivity. It is really harmful to young developing brains. But the fact of the matter is, human beings have known lead is dangerous for a really long time. The Greeks knew this. Benjamin Franklin wrote about the dangers of lead. People actually had a kind of a very natural fear of it. And yet, lead still ended up in so many everyday consumer products. As a result, lead poisoning is arguably the longest running public health epidemic in American history. And this Dutch Boy character is a clue as to how that happened; how the lead paint industry convinced us to ignore these health risks and pushed this poison into our homes all in the name of profit.

KAI: And so our question in this episode is: Why hasn’t this industry been held accountable? And how are kids still being poisoned? That’s what’s at stake.

***

WERTH: So Kai, I want to introduce you to some people.

[SOUND OF TRAIN]

WERTH: I went out to record an interview not too long ago.

[SOUND OF TRAIN]

WERTH: It was in the far reaches of New York City.

[BUZZER INTERCOM]

MOTHER: Hello?

WERTH: Oh, hey. It’s Christopher from WNYC.

WERTH: When I got there, three story walk up. Old building,

[FEET ON STAIRS]

WERTH: I go up this rickety wooden staircase. And at the top, I meet this family.

WERTH: Hello?

MOTHER: Hi.

WERTH: Hey!

WERTH: This mother and her four very beautiful children.

[SOUND OF CHILD, DOOR CLOSING]

CHILD: Hello. I need to talk, wait.

WERTH: All under the age of five. All in this small, very very sparsely furnished three-bedroom apartment.

KAI: And we’re where in New York City now?

WERTH: Well, see that’s the thing. I cannot tell you where we are or who these people are. This woman is, she’s a victim of domestic abuse she’s hiding from the father of these kids. So she’s in this program that’s placed her in this apartment.

KAI: Right.

WERTH: So this place, while it’s not particularly fancy, it’s kind of a refuge for her and these kids.

KAI: It’s her safe space.

WERTH: It’s her safe space.

[SOUND OF KIDS]

WERTH: But then she tells me this story about how, she’d lived there for a few months, maybe half of a year, and she started to notice something about the kids.

MOTHER: After while I keep seeing them with this white stuff on their mouth. I'm like…

WERTH: It was like this white powder.

MOTHER: So I’m like, “What’s going on?”

WERTH: And so she asks one of her older daughters, “What is this? What’s on your mouth?” And the little girl tells her.

MOTHER: Oh mommy, the paint from the wall. I’m like, “Why are you all eating the paint from the wall? That’s not nice. That’s nasty.”

KAI: Oh god, so then what does she do about it?

WERTH: Well at first, she didn’t immediately realize this is a problem.

[SOUND OF KIDS]

WERTH: But then.

MOTHER: I took them to the doctor to get their physical done for school, and the doctor called me back with the results.

WERTH: These kids had been exposed to a lot of lead.

MOTHER: The kids have lead poison.

WERTH: What were the kids levels?

MOTHER: My oldest daughter was 15 and the other oldest one was 16.

KAI: So those sound like big numbers but I don’t, how much are you supposed to have in your blood?

WERTH: So the Centers for Disease Control says no level of lead is safe. And it recommends that health departments should take action when a child tests above 5. So these kids are three times that number and in New york City if your kid tests at 15, 16 the health department knocks on your door within a couple of days to conduct an inspection.

MOTHER: They came and check the windows and stuff like that and they find the lead.

WERTH: They found lead all over the place. I mean when they go in they stamp it with these red letters that say “lead paint” and it was on the doorframes, it was on the windows. I went into one of the kids bedrooms and you could actually see bite marks on the windowsill.

KAI: Oh my god.

WERTH: And all of this chipping paint.

CHILD: I got water.

WERTH: Oh you did? Were you thirsty?

WERTH: And one of the four-year old girls was saying, “We eat the windowsill.”

CHILD: I biting the window.

WERTH: Why have you been biting it?

CHILD: I biting it.

WERTH: Don’t bite the window, sweetie. Don’t bite the window.

KAI: Wait, what makes kids wanna eat paint in the first place?

WERTH: Well, you know, here’s like one of the cruelest parts of this lead situation is that the lead that went into paint has a very sweet taste.

KAI: That is horrific.

WERTH: Right, so they get a taste of it and they want a little more, and they want a little more. So they keep eating it.

KAI: So what can she expect to happen as a consequence?

WERTH: Well, lead is a really potent neurotoxin. It causes brain damage. And her landlord is now supposed to fix this problem. At least, that’s what the city requires. But at the time I met this family, he was not getting the work done.

WERTH: Are you worried.

MOTHER: Yeah of course I'm worried. Like I read it up and I see a lot of stuff like you can get affected after the like It’s just frustrating because there still going to the wall. I don’t know what to do to stop them from going to the paint.

KAI: So Christopher, I followed the story about lead in the water in Flint, of course. But if I’m honest I thought lead paint was a thing of the past.

WERTH: Lead paint was banned in this country 40 years ago, but a lot of that old paint is still with us and that’s what poisons the most kids. It is still haunting us. And here's the thing -- you start to dig into the past and you find that the lead industry knew this paint was dangerous.

ROSNER: Everyone knew about lead poisoning. This was not a secret.

WERTH: So I spoke with this guy named David Rosner. He’s a public health historian at Columbia University. And he says what the lead industry had to do was transform lead’s reputation.

So there was a concerted effort to kind of make this a consumer item by // generally advertising it as a healthful product: a modern, healthful product.

WERTH: The pitch was that this paint was so good, it will protect your home and make it safer. And if you go to his office he’s got these massive filing cabinets. He has been looking at the history of lead poisoning for a really long time. And he’s collected all of this historic material from the lead industry.

ROSNER: I wanted to show you a couple of these things.

WERTH: So he's got internal company memos that they were trading back and forth. He's got these manuals for how to mix this stuff mix this lead paint.

ROSNER: Hundred pounds of lead heavy paste.

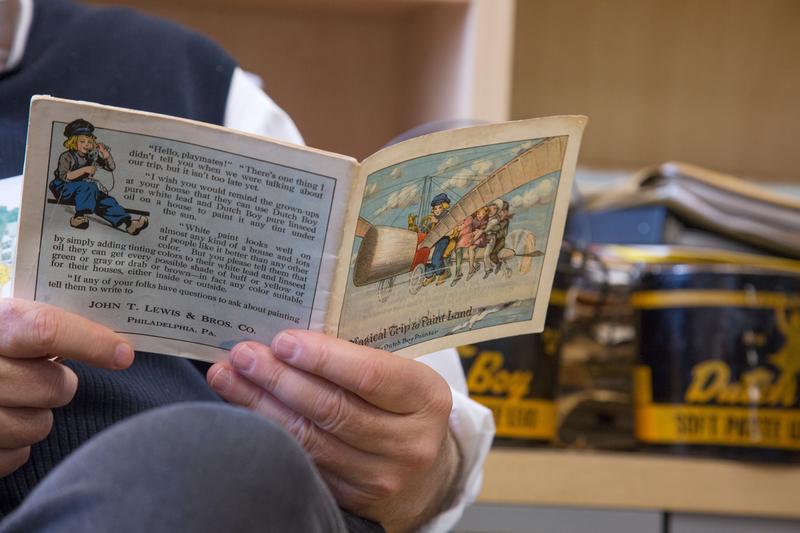

WERTH: But there's this one thing that really stuck out for him that he wanted to show me which was this kid's coloring book.

ROSNER: This is what a school. It's called the Dutch Boy conquers Old Man Gloom.

WERTH: So this coloring book was published by the National Lead Company in 1929. And on the cover is Dutch Boy he’s holding hands with these two little kids and the whole coloring book has this story in it. These kids they live in this really drab really dingy apartment or house.

KAI: No paint on the walls.

WERTH: No paint on the walls it's really gray. And that home is personified by this character Old Man Gloom.

ROSNER: He's dressed in old black 19th century clothes. He has a big top hat. He has a long ugly beard he's using a cane.

WERTH: And lo and behold as you turn the page Dutch Boy comes along and he's carrying a can of paint and he's very colorful that he could be straight out of a Disney movie.

ROSNER: The children say, "Oh could you invite him in. He looks like such a fun guy. Maybe he'll make our gloomy life a little happier." And he comes in and he teaches the kids how to paint their room paint their furniture their toys their walls everything that he shows how much fun it'll be. "For feeling blue you're not to blame. Come let me show you a new game. This famous Dutch boy led of mine can make this playroom fairly shine. And suddenly this room which is this kind of dingy greenish gray becomes this bright playroom where everything shines. And old man gloom says, "I've been undone by a Dutch Boy Paint and Dutch Boy lead."

WERTH: Inside, was a little coupon for a can of lead paint that read “Give coupon to mom or dad.”

ROSNER: Everybody thinks the tobacco industry invented all this stuff. Lead industry was putting out these ads aimed at children that youth they had their version of Joe Camel you know well before well before Joe Camel was invented.

[MUSIC]

WERTH: This Joe Camel strategy worked. Dutch Boy would appear at parades and in newspaper ads extolling the benefits of lead. People were convinced it was safe. In the period leading up to this coloring book, the lead paint industry was booming, pumping out around 160,000 tons of lead at its peak.

And not just Dutch Boy. Lead was cheap and plentiful. Sherwin Williams made lead paint. Benjamin Moore.

And the real upside was that lead is opaque -- the lead that went into paint was a fine white powder that created a solid, durable surface. It just had to be mixed with a little linseed oil.

ROSNER: Each gallon of lead paint had about 16 pounds of lead in it. Half the container was lead

WERTH: But because lead went in as a powder, it also comes off as an invisible dust that can cover everything. Floors, windowsills, children’s toys. This is not just about kids who eat paint. Lead dust enters the bloodstream very easily.

ROSNER: Children were coming down with seizures and going into comas and dying because they were touching these walls getting stuff on their hands and then putting their hands in their mouth

WERTH: It was also in this era that companies such as General Motors and Standard Oil began adding lead to gasoline -- to improve engine performance.

LEAD GAS ADVERT: And that’s why ethyl gasoline brings out the full power and performance of your car

WERTH: This introduced large quantities of lead to the air everyone was breathing. And according to the internal documents Rosner’s pieced together, people in the lead industry knew exactly what kind of effects all of this was having on people’s health. And they got away with it, he says, by going after the science. They went after pediatricians and researchers who were raising the alarm. They threatened them with lawsuits. But -- as the evidence mounted, as more and more kids were poisoned -- the Lead Industry Association took another tack. They passed this off as a problem that only affected people of color.

ROSNER: They say this in their memos.“The only people who were really victimized by it are Puerto Rican and Negro people. And we can't do anything about that, unless we really rebuilt the housing. Ho ho. That's not going to happen.” Or alternatively, and they say this, “Educate their parents not to let them eat lead. And how does one accomplish that task.” They say. “How can we ever educate them?” You know this was an indication of the racism of a culture.

[STREET AMBI UP]

CARLITO: This street right here was one of the most populated streets in East Harlem.

WERTH: In New York City, Carlito Rovira witnessed that racism first hand. In 1969 -- at the just 15 years old -- he joined The Young Lords, a Latino grassroots political organization.

And at a time when few public officials were willing to take on this problem, groups like The Young Lords and The Black Panther Party, they began knocking on doors with a team of medical students, testing kids in their neighborhoods.

CARLITO: And we would have literature ready to explain that we are testing because basically cause this system is trying to kill you.

WERTH: Rovira remembers one child in particular, a little boy in a Puerto Rican family with very high lead levels.

CARLITO: The kid resided on this block. And if I'm not mistaken he lived in this building right there.

WERTH: Describe what he was like, though...

CARLITO: He was wobbly. He had this fainted look. And we were concerned. We were concerned.

WERTH: A couple days later, Rovira and a couple of other members came to take him to the hospital.

CARLITO: One of the medical students put on a suit and it was to set an impression to the people at the emergency room. And you had to do that in those days because basically they didn't give a shit about people poor people coming in and telling them that they were discovered to have some kind of poisoning.

WERTH: You didn't think that he would get the proper treatment if you took him.

CARLITO: No. We went there. They knew who the Young Lords were. That's all the institutions were a little bit apprehensive about stepping on our toes. Because we were young and we were stupid and crazy. So I got to tell you how we were. We were we were defiant. And they didn't know how to deal with us.

KAI: They were acting as these first responders.

WERTH: Yeah, but even this late in the game -- the way that everyone thought about lead was very very different from the way that we do now. People still thought of it as something that really only caused harm at high levels.

But then SOMEONE came along who would fundamentally change the way we think about what lead does to young, developing brains.

NEEDLEMAN: I was a pediatrician, practicing pediatrician. I made housecalls.

WERTH: This is Dr. Herbert Needleman.

NEEDLEMAN: And in my training at the Children's Hospital Philadelphia, I treated my first case of lead poisoning, a very sick little Hispanic girl.

WERTH: Needleman passed away in 2017, but he spoke about this case in an interview years ago that shows his way of thinking. This kid was living in a house riddled with lead paint.

NEEDLEMAN: I told her mother what I had been trained that is if she was re-explain she was essentially doomed. I said, “You have to move out of that house.” And the mother said to me, “Where am I going to move any house that I can afford is no different than the house I live in.” And that shocked me and smartened me up.

WERTH: He wondered: if it’s killing kids, or nearly killing them, at high doses, what about all these other children who aren’t in the hospital, but live in the same houses? Live in the same neighborhoods? How much lead is in their bodies?

J NEEDLEMAN: He was looking for what happens with lower doses of lead.

WERTH: This is Herbert Needleman’s son, Joshua Needleman.

NEEDLEMAN: What happens with children who are exposed to lead that was considered safe? What effects do they have? And how can we measure that?

WERTH: And answering that question was actually a really big challenge. There was really no EASY way to find out how much a kid had accumulated over several years. But then one day around 1970, Needleman was sitting in his office in North Philadelphia, and something caught his attention.

[SOUND OF KIDS IN SCHOOLYARD]

J NEEDLEMAN: He said he could look out his window and see a school yard there.

WERTH: It was recess. There were children playing outside. And he thought, what if I were to go into that school and collect those kids’ baby teeth.

KAI: Their baby teeth? Why their teeth?

WERTH: Well, what Needleman knew, was that a lot of the lead that gets into our bodies gets locked up in our bones. Lead behaves a lot like calcium in that way, even though nothing else about it is anything like calcium.

But essentially lead acts as a kind of imposter. It replaces calcium not just in bones, but in our red blood cells, which obviously carry oxygen through our bodies; and in our neurons, which allow our brains function. That’s what makes lead so destructive. But if it’s in these kids’ bones well then it’s also in their teeth.

J NEEDLEMAN: And so he realized that children in elementary school were losing their teeth and that the level of lead in their teeth also reflected lead in their bone and lie reflected their exposure over time. So began to collect teeth and analyze it for lead

WERTH: So Needleman, he started to develop this pretty elaborate, kind of crazy medical study that would come to be known as the “Philadelphia Tooth Fairy Project.” He had this network of dentists and teachers at a number of different schools. And he’d swing by every week or so. He’d pick up a few new teeth. He had their parents’ consent. And he’d note who the kid was and he’d ask the teachers, you know, what is this child like as a student?

SHAPIRO: There was some very strange incidents during this time because we were offering the children money for their teeth.

WERTH: Irving Shapiro was a colleague of Needleman’s at the time. He’s an expert on tooth formation. Needleman was offering a silver dollar for each tooth.

SHAPIRO: I remember one day a guy appeared in my lab. A very fierce looking individual. And he said I want money. And I said What do you mean. He said I've brought you the teeth. And he had a handful of bloody teeth in his in his hand and he wanted to. He wanted money for each of those teeth that he brought in. And... I gave him the money. He scared me silly.

[MUSIC POST]

KAI: And did they those use those teeth?

WERTH: No, but in a few years’ time, they did manage to examine 760 teeth from first graders in Philadelphia. And of course, what they found, black students had much higher lead levels than white students. That’s what you’d expect given everything I’ve just described. But what was more surprising -- and Shapiro says this -- was that almost all of these kids -- whether they were white or black, suburban or urban -- most of them had been exposed to -- what at the time even -- were considered very, very high levels of lead... from the time they were babies. And this shocked a lot of people.

SHAPIRO: What we discovered affected so many children. We were not talking about a few children. We were talking about a large number of children. And when you play that out across the country, the number of kids who were involved was sufficient to make people wake up, make the health authorities wake up to the fact that there was a devastating event that was taking place in our cities In fact, no children were were unaffected by it because there was just, lead was ubiquitous.

KAI: Now that they know it’s ubiquitous meaning now that they know there’s white kids being affected.

WERTH: Exactly. And as Needleman kept pursuing this question — he later went on to Harvard where he continued this research — he found that this exposure -- even at levels that were considered miniscule at the time -- was causing real damage.

SHAPIRO: And we came to the conclusion that lead was a poison and there was no safe level of lead at all in the human body.

KAI: So what effect did this research have?

WERTH: Lead paint was banned in 1978. It was also in the 1970s that the U.S. began phasing lead out of gasoline. And it wasn’t all due to Needleman, but certainly -- many of the people I’ve interviewed told me -- his research was essential in pushing those policies forward.

KAI: So he won.

WERTH: Average lead levels in the United States have dropped more than 90 percent since the 1970s. But, as we know from those four little kids I told you about earlier…

[SOUND OF KIDS]

WERTH: That doesn’t include everyone.

KAI: Coming up… how we missed our chance to solve this problem for good.

SEG C

WERTH: You know, Kai...

[SOUND OF KIDS CRYING]

WERTH: We went back to that mother and her kids who are dealing with all of this lead paint.

MOTHER: Go in your bed. Go in your bed. You too madam.

WERTH: The landlord was supposed to have taken care of this problem within five days. And I assumed this was over and done with. But over two months since I first walked through her door, nothing has been done.

MOTHER: My kids is still picking the paint off the wall.

WERTH: They're still doing it?

MOTHER: Yeah they're still eating it.

WERTH: Oh God. Oh god.

MOTHER: I don't know what I should do. It's frustrating.

WERTH: I can imagine. And you can't keep them away from it.

MOTHER: It's in there room. So you know you sleeping at night. You don't know what they're doing in here. It's like you wake up in the morning you see paint all over the floor, like, “You all was eating the paint? Yes mommy. Why? I don't know.

KAI: And you know listening to her, Christopher, what is striking is that here is a family that turned to the city, to the government looking for safety and we have failed her, repeatedly. We put her in a facility, in a house that had poison on the wall. And the poison is still there.

WERTH: Yes, but this is how we’ve set it up. We’ve essentially made a decision to use kids as canaries. And it’s estimated there are over a million of them in this country. We wait until they’re shown to have an elevated blood level and only THEN do we try to eliminate the source.

And I think we need to ask ourselves, are we really okay with that?

You know, after he proved in the 1970s that lead was causing all this harm, almost immediately Herbert Needleman started pushing public officials to take a more preventative approach. He really thought we could eradicate this for good.

HENRY WAXMAN: I'd like to now call forward to testify Dr. Herbert L. Needleman professor of psychiatry and pediatrics

WERTH: In 1991, he testified before a House committee hearing pushing this idea: That if we were willing to spend the money, we could solve two problems. One, go into all these old homes and remove the lead paint. And two, create jobs by training people in these neighborhoods to do that work.

NEEDLEMAN HEARING: If you map where lead is piled up in super abundance and if you map where housing is and decent housing is in short supply and if you map where jobs are in short supply the three maps are virtually identical.

WERTH: But this was the era of small government. And in the end, he couldn’t get it through. Needleman’s vision was never realized.

KAI: So we’re just screwed? That’s where we’re at?

WERTH: Well, actually we’re at a very important moment in this history right now. Because there’s this different approach that seems to be gaining some traction.

FITZPATRICK: Are you there.

WERTH: I'm here.

FITZPATRICK: Okay.

WERTH: Okay

WERTH: This is Fidelma Fitzpatrick. She’s a lawyer at Motley Rice, which is a firm that was involved in a lot of the big cases against the tobacco industry and the asbestos industry. And they’ve been going after the companies that created this problem in the first place.

FITZPATRICK: It is mind boggling to me mind boggling that companies could look at the legacy of what they have done and not feel any twinge of corporate responsibility, not believe that they have to be good corporate citizens to solely become part of the solution. They don't want to solve the lead poisoning crisis that exists in America. They don't care about it. And so that's where the law steps in.

WERTH: In California, ten cities and counties got together and sued several paint companies, including Sherwin-Williams and the National Lead Company, which is now called NL Industries.

[NEWS CLIPS] Several local counties will be getting a huge pay out after a landmark court decision which involves lead paint

A California judge ruled Sherwin-Williams Company, NL Industries and conagra grocery products knew lead paint was dangerous

WERTH: And in building this case, Fitzpatrick used all those historical documents David Rosner has collected as proof these companies really knew they were selling dangerous products all along.

It took 18 years. But in the fall of 2018, the lead paint companies were forced to pay $400 million dollars, which will be used to fund lead abatement programs.

Fitzpatrick: And that's that's really what the California case was about forcing accountability on the companies that should have taken that mantle up voluntarily but chose not to.

KAI: Christopher, I don’t know if that’s exciting or depressing -- that we can’t count on government to help families like the one you met.

WERTH: Right, not without a willingness to pay for it. And you know, given that local governments already spend a lot of money dealing with lead paint, I mean testing kids, inspecting homes -- And Fitzpatrick says cities all over the country should be thinking about how to make these paint companies pay their share, either voluntarily or through the courts. And it’s interesting, if you zoom out from this lead issue, this idea has some pretty broad implications for how we hold corporations generally responsible for solving a lot of really expensive problems…

KAI: This whole story is frankly a stark reminder about how justice works, period. It’s not good enough to just say, ok, let’s stop doing this awful thing -- let’s ban the use of lead paint -- and then move on. You have to deal with the damage that’s already been done. And that means somebody has to be held accountable for it -- to take some of the immense profit they made, and fix what they broke. Only then can we actually move forward.

CREDITS

The Stakes is production of WNYC Studios and the newsroom of WNYC.

This episode was reported by Christopher Werth. It was edited by Karen Frillmann, who is also our executive producer. Cayce Means is our technical director. Jim Schachter is vice president for news at WNYC.

The Stakes team also includes… Amanda Aronczyk, Christopher Johnson, Jonna McKone, Jessica Miller, Kaari Pitkin, and Veralyn Williams. With help from Hannis Brown, Jonathan Cabral, Michelle Harris, and YOU.

Join us by signing up for our newsletter at TheStakesPodcast.org. You get all kinds of cool stuff, like bonus content and musings from me and, maybe most importantly, a chance to tell us about yourselves and help us find stories. You can also hit me up on twitter at kai_wright.

Thanks for listening.

END