A History of Persuasion: Part 1

[Theme music]

KAI WRIGHT: I’m Kai Wright and these are The Stakes. In this episode. cannibalistic worms and thought reform.

[End theme]

KAI: Okay, Amanda you've you've got the letter.

AMANDA ARONCZYK: I brought the letter with me today. Yes.

KAI: And this is a letter from whom?

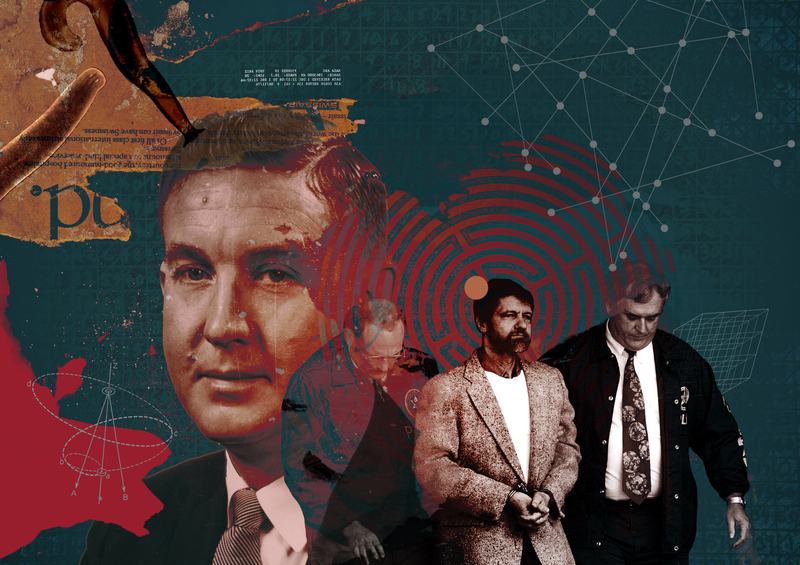

AMANDA: This is a letter I got last year from Ted Kaczynski

KAI: The Unabomber.

AMANDA: Yes

KAI: I was disturbed to learn you had been writing the Unabomber.

AMANDA: Should I remind people..?

KAI: Yes. Tell us tell us quickly who he is.

AMANDA: Right. If you don't remember who the Unabomber is -- from 1978 to 1995 he sent these bombs that he made himself to 23 victims. He killed three people.

KAI: Arguably our most infamous domestic terrorist. And it was all because he was freaking out about technology, right?

AMANDA: Yeah, he was targeting people who he saw as symbols for technology.

KAI: So why did you write him?

AMANDA: Well, I wanted to know more about WHY he did what he did. And I really did not expect him to write me back. You know, he does not engage with journalists.

KAI: But he did write YOU back. So what did he say?

AMANDA: Well, what's interesting is that he is still to this day freaking out about technology. You know, he's in a supermax prison in Colorado. I’m sure it is extremely limited access to computers. Probably they don’t get to go on the internet at all. And he’s been there for more than 20 years, which is before many of the technologies we have today were so widespread.

KAI: Right, like he's probably never even seen or even held an iPhone, right?

AMANDA: No. Probably not, and yet, when he wrote me back that was what he was worrying about.

KAI: Smartphones.

AMANDA: Smartphones. Specifically how these devices have captured our attention. So, he gives me this reading list, and it includes articles with titles like: "Silicon Valley is addicting us to our phones,” “Is the Internet making us crazy?,” Our minds can be hijacked"...

KAI: Wow

AMANDA: And the more I dug into Kaczynski, I realized that these fears are around some psychological tricks that he's been worrying about for a very long time. And I think it explains why he tried to kill some of the people he targeted.

KAI: Huh.

AMANDA: And I actually think it tells us a lot about why many of us are freaking out about technology today.

[music]

KAI: That collective freakout actually began decades ago. And it’s less about technology than our fears about the extent to which we can be manipulated by unaccountable powers. But what’s different right now is scale.

TRISTAN HARRIS: We're running this vast psychological experiment that humanity has never been through before of what happens when two billion people are jacked into an infrastructure.

KAI: And so over the next three episodes, our reporter Amanda Aronczyk is gonna tell the winding story of the science of persuasion and our collective reaction to it. We’re gonna begin that story with a largely forgotten psychologist whose experiments once provoked as much anxiety as Facebook does today.

[Sound of tape rewinding]

ANNOUNCER: This is University of Michigan Television...

AMANDA: So it’s 1958, and you’re hearing a film called “Battle for the Mind.”

ANNOUNCER: Now here is your host for today’s program, James McConnell.

AMANDA: In walks psychologist James McConnell. He’s in his 30s. He’s got short dark hair styled back. He’s wearing a dark suit. And well you might not recognize his name, he was famous back then. He was the kind of psychologist who you would call on to explain unusual human behavior. Like this very strange event that took place at the end of the Korean War.

JAMES MCCONNELL: Why did hundreds of American soldiers in Korea denounce their native land, embrace communism and turn on their fellow prisoners?

AMANDA: There are these 21 american soldiers who refused to come home.

POWs: Does anybody want to go home? Nooo!

MCCONNELL: The answers to these questions are what we will seek today, as we investigate the behavior of American prisoners of war in Korea. During what many people choose to call the strangest war we have ever fought.

AMANDA: So these were young soldiers...

POW: My name is Louie Griggs and my home is in Jacksonville, Texas.

AMANDA: And they chose Communist China over America.

POW: My name is Aaron Wilson, from Urania, Louisiana.

AMANDA: So the question that McConnell and everybody was asking, is what had happened to these soldiers?

WOMAN ON TAPE: My estimation of this situation is brainwashing.

AMANDA: Brainwashing!

[Music from tape]

AMANDA: This was all over the news. And it created a kind of panic. Americans assumed that the Communists had found a kind of dark magic to crack open people’s minds and control them from within.

MCCONNELL: This was the first time in history that American soldiers had chosen to remain with the enemy because they preferred the enemy's way of life to ours.

AMANDA: When many of these guys do come back, the army takes them and interrogates them at length and wonders, you know, what happened to them? You know, what were they subjected to?

MCCONNELL: First there was the technique of fear.

AMANDA: The fear of things to come

MCCONNELL: Coupled with this quite often there was the technique of hope.

AMANDA: The hope that one could get out of being punished

MCCONNELL: And if this didn’t work another technique was self-confession. Make him confess to just a little sin, and then a bigger one and then a bigger one until finally he paints a monster of himself.

AMANDA: Now of course these guys weren’t actually brainwashed. But back then this incident -- it showed that people’s psychological frailties could be understood. And what makes that so terrifying is that you never know who will exploit that understanding.

MCCONNELL: Well, tell me Colonel and I think this is very interesting if we get into another battle does the army expect that the men who are captured will be indoctrinated or brainwashed?

WOODMAN: Very definitely so. We very definitely feel that we will be up against this new weapon.

ANNOUNCER: This has been “Battle for the Mind: The story of a new and dangerous psychological weapon.”

AMANDA: So, here’s why this matters:

KAI: Alright.

AMANDA: The psychologists who studied brainwashing and what happened in the Korean War inadvertently wrote the playbook for how to weaponize these techniques.

KAI: It's a thing that's like a shiny new tool.

AMANDA: And it's a tool that is proving to be pretty useful.

KAI: Right.

AMANDA: Okay, so the Department of Defense is very interested. The military is very interested and the newly-formed CIA is very interested in all of these psychological techniques. And so money pours into the field of psychology.

KAI: From the government?

AMANDA: From the government. And there’s like this arms race that begins -- for mind control. And McConnell, he’s young, he’s ambitious. He sees the opportunity and he goes and gets a contract with the Defense Department.

LARRY STERN: In 1958, he was asked to be on this working panel … And he basically is writing all about motivation and persuasion techniques and persuasion was the good way of referring to brainwashing back then.

AMANDA: So this is Larry Stern. He is a professor at Collin College in Texas. And Larry discovers that McConnell was busy cataloguing all of these experiments into how human behavior could be controlled.

STERN: And then you know he kind of writes that you know you can combine conditioning techniques with group pressure with propaganda, chemical injections, hypnosis, all kinds of things. And he put in a grant proposal to literally do that kind of work.

AMANDA: Essentially he wants to do experiments on humans, using sensory deprivation. But this is considered like, way too out there, too coercive, and he doesn’t get funded for this. So McConnell decides to go back and work with this creature that he’d worked with when he was a grad student. He decides he’s going to work with worms.

[Music from “Heads or Tails”]

NARRATOR: What started you working on flatworms in the beginning?

MCCONNELL: Well, I think it was purely coincidental or even accidental, Mack, back in 1953...

AMANDA: So what McConnell wants to do is he wants to look at the very roots of behavior. He wants to see -- Can he train this very, very simple organism.

MCCONNELL: The flatworm is the simplest organism in nature that has a similar nervous system to that that we have...

AMANDA: And so he decides he's going to do something that psychologists call “classical conditioning.”

MCCONNELL: You may remember, Mack, that Pavlov was really one of the first people to do this. He took a dog and if the dog was hungry…

KAI: So like the dog with the bell?

AMANDA: That’s right, you know this experiment. The dog associates a sound with food. And then when it hears this sound -- even when there is no food -- it still salivates.

KAI: Right.

AMANDA: And McConnell wants to do the same thing but this time with worms.

KAI: Oh they want to teach the worm.

AMANDA: Exactly. They want to teach the worm a behavior.

KAI: Oh wow.

AMANDA: And back then people are like, that’s crazy!

KAI: It’s a worm!

AMANDA: It’s a worm!

KAI: (laughs)

MCCONNELL: Let me show you, this was the prototype...

AMANDA: So they set up this makeshift lab and they've got this contraption. It's a little trough of water which looks like a lap pool for worms. And there are two lights to light up the pool.

STERN: Literally they did this in McConnell's kitchen...

AMANDA: In McConnell’s kitchen!

STERN: Said it cost them about six, seven bucks.

AMANDA: (laughs) Oh my God, where'd they get the worms from?

STERN: They went to the pond…

MCCONNELL: Which was outside the biology building, and we got down on our stomachs and we grubbed around on the bottom...

AMANDA: You know, these worms are everywhere. They fill up a bucket and they bring it back to McConnell's kitchen. And they take one of the worms and they put it in the trough.

MCCONNELL: And this little water worm runs back and forth in a nice straight line on the bottom of the trough.

AMANDA: And the worm is swimming and they add an electric shock. The worm scrunches up. And then they pair that shock with a light. So shock light - worm scrunches up. At a certain point when the worm is trained you remove the shock and you just have the light. So light comes on, worm scrunches. You have classically conditioned the worm to do a behavior.

MCCONNELL: All of our work has shown I think pretty clearly that these organisms are quite capable of learning and that they can learn even fairly complicated things like a hexagonal maze.

STERN: After he did the simple conditioning which paired light with a shock he then would put them in a maze and the worms would slither along and they had to go either left or right and you would basically use rewards and punishments to try to get the animal to behave one way rather than another.

AMANDA: So McConnell figures out how to do this -- how to train the worms. And then he decides he’s going to take it further. So if you have taught one worm how to scrunch...

KAI: Uh-huh.

AMANDA: ...Could another worm learn that behavior without being taught that behavior.

KAI: How do you mean?

AMANDA: Well he wants to transfer the memory of scrunching to an untrained worm and he decides that the way to do that is he's going to grind up the worm that has been trained to scrunch and he's going to feed it to the worm that doesn't know anything. And he's going to see if the worm that doesn't know anything is going to ingest that knowledge and then do that behavior.

KAI: Like cannibalism is going teach -- he's going to learn through cannibalism.

AMANDA: Right. The memory is a chemical that's in the body and it can be transferred to another creature by eating it.

KAI: Is that true? Did it work?

AMANDA: Well, it did seem to work actually.

KAI: Really? So I can eat you and learn everything about you?

AMANDA: I wouldn't assume that what happens to the worms happens to you and I. So I feel like that's not appropriate. (laughs)

KAI: OK. Well that's good to know.

AMANDA: Yeah, I mean back in the day people had trouble replicating it. But since then, there has been some research that suggests he was right. Not about the cannibalism part necessarily, but that memories might exist outside the brain, and in the body.

KAI: That is actually really quite mind blowing.

AMANDA: It is mind blowing, yeah.

KAI: Did they ever get past worms?

AMANDA: Yes. They start to experiment on rats.

KAI: They had rats -- they were grinding up rats and then feeding them to each other?

AMANDA: Yes. They try it with rats with octopus with bees. And this is like this kind of trend in science to attempt to do memory transfer experiments.

STERN: You know, this all sounds very peculiar, but there were close to 200 labs that were actually going and conducting memory transfer experiments in the heyday.

[Steve Allen Show Theme]

AMANDA: This memory transfer business makes McConnell a celebrity. He appears on TV shows like Mr. Wizard and The Steve Allen Show…

STEVE ALLEN: I’m Steve Allen.

AMANDA: His work gets featured in Newsweek and Time and then he goes on and writes a best selling textbook. He's basically a pop psychologist with this uncanny ability to make money.

NICKLAUS SUINO: Yeah, he was probably better off than most people I knew up to that point in my life.

AMANDA: Nicklaus Suino worked for James McConnell back in the early 1980s. And at that point McConnell had moved into a 12,000 square foot house.

SUINO: The wine cellar was as big as some people's apartments. It was absolutely enormous. Gigantic living room. I wouldn't be surprised if the living room alone was two thousand square feet. Pool inside the house. Greenhouse inside the house with lots of orchids. Really nice place.

AMANDA: But Kai

KAI: Uh huh

AMANDA: There’s actually this other... like stranger reason why McConnell remains this figure in the history of psychology.

KAI: Stranger than feeding worms to each other?

AMANDA: Maybe more shocking?

KAI: Okay

AMANDA: This is the reason why I wrote to Ted Kaczynski in the first place. And that is coming up next after the break.

+++

KAI: Hey Stakes listeners. Over the next few episodes, we’re trying to bring some historical context to the intense anxieties so many of us feel right now about digital culture. So we asked you about your own relationship with technology.

ROSEMARY MISDARY: What is the most ridiculous situation where you’ve used your cell phone?

VOICE 1: I was going around Paris on one of those electric scooters and I was Snap chatting. But the kicker is I also had a cast on my left arm. So my casted hand was holding the scooter, while my right hand was Snap chatting.

VOICE 2: My friends would like call me with something very personal and I would just put the phone on speaker and just like check Instagram.

VOICE 3: I mean I was sure I was checking Instagram during High Holy Day services.

VOICE 4: It’s on the toilet. And it’s me just sitting there doing my business, but also trying to get busy on Hinge.

KAI: That’s a bit of what we’re hearing, but keep sending your experiences to me. Just record a voice memo and email it to TheStakes@wnyc.org. Thanks.

+++

AMANDA: On the afternoon of November 15th, 1985 Nick Suino was heading out to work at James McConnell’s house.

SUINO: I actually rode my bicycle out, it was about seven mile ride.

AMANDA: And he stops his bike at the mailbox.

SUINO: Loaded up this stuff in my arms...

AMANDA: He heads inside...

SUINO: Go through the garage, go into the kitchen...

AMANDA: And says hello to McConnell.

SUINO: One of my jobs almost every time I went out there was to open the mail. And on that particular day, he was having breakfast or coffee or whatever. I opened a few letters and then there was a package. It was wrapped in brown paper. And it was wrapped with that fibre tape. And I cut it open with a knife…

[Sound of explosion]

REPORTER: Last November, graduate student Nicklaus Suino opened a package he thought was a book addressed to the professor he worked for.

SUINO: I suddenly felt a strong pressure, opening the two sides of the box. And at that moment the box exploded.

REPORTER: The intended victim was his boss, University of Michigan professor James McConnell.

MCCONNELL: And I kept saying, who hates me? You know who can hate me this much to send me a bomb?

AMANDA: James McConnell didn’t know it at the time, but he was a target of Ted Kaczynski

NEWSCASTER: The Unabomber remains the most elusive terrorist bomber in U.S. history. Sixteen bombs over 17 years...

AMANDA: So Nick Suino and James McConnell were actually pretty lucky.

KAI: Because they didn’t get killed, because the Unabomber killed people.

AMANDA: That’s right, and this was the 10th bomb and it’s the next bomb that was fatal.

KAI: Mm.

NEWSCASTER: Officials are warning everyone to be on guard for a potentially deadly delivery from a man dubbed the Unabomber.

AMANDA: The Unabomber had been targeting what seemed like totally random victims, there’s a president of an airline...

KAI: Yeah.

AMANDA: ...a geneticist, a computer scientist...

REPORTER: The FBI believes he has a particular hate for computers.

AMANDA: Nobody could figure out who he was. They spend years investigating this.

KAI: Yeah.

AMANDA: At the time it was the longest FBI investigation on record and the most expensive. And then this really unexpected thing happened

NEWSCASTER: In an extraordinary decision The Washington Post and The New York Times have published today, the complete diatribe which the Unabomber had sent them three months ago...

AMANDA: So one day you wake up in the morning you open up your Washington Post and there’s this huge insert, 8-page insert and it’s titled “Industrial Society and Its Future.”

NEWSCASTER: This so called manifesto was a pretty wide ranging attack on what this particular terrorist finds wrong with society.

AMANDA: And the manifesto starts with this line: “The industrial revolution and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race...

NEWSCASTER: “...human race. He calls for a revolution against the industrial system, not necessarily an armed uprising, but certainly a radical and fundamental change in the nature of society.”

AMANDA: It's basically this diatribe and it’s a list of complaints. You know, there are too many people, man is isolated from nature, and this one I think is super interesting -- technological progress marches in only one direction and it can never be reversed.

REPORTER: His ideas are not far out of the mainstream. He’s crazy but many people share many of his ideas.

KAI: Okay, but what does all of this have to do with James McConnell and his worms?

AMANDA: Well this is what I have been wondering, like, why would somebody who hated technology, hated airplanes, hated geneticists, hated electrical engineers, hated computers -- what would they possibly have against a psychologist?

KAI: In our next episode, McConnell’s ideas for controlling human behavior take a very dark turn.

STERN: He's really on this kind of crusade. He says: “I believe the day has come when we can combine sensory deprivation with drugs, hypnosis and astute manipulation of reward and punishment to gain almost absolute control over an individual's behavior...”

KAI: That’s coming up, on The Stakes.

CREDITS

The Stakes is production of WNYC Studios and the newsroom of WNYC.

This episode was reported by Amanda Aronczyk.

It was edited by Christopher Werth.

Cayce Means is our technical director.

Karen Frillmann is our Executive Producer.

The Stakes team also includes…Jonna McKone, Jessica Miller, Kaari Pitkin, and Veralyn Williams…

With help from…

Hannis Brown, Cheyann Harris, Michelle Harris, Rosemary Misdary and Kim Nowacki.

And hit me up on twitter, @kai_wright. Thanks for listening.