Tell Me Your Politics–But Do It In Verse

( CityLore )

[music]

Speaker 1: Everyone needs me to vacuum bungalows, apartments, Airbnbs, weekly, seasonally, every so often, liberal, moderate, conservative. Where I'm from, everyone needs me to vacuum.

Speaker 2: I am from a four Micah top dinette table around which the family argued March on Washington, extremism in defense of liberty, women's lib, academic freedom, Vietnam, Stonewall.

Speaker 3: I am from $40 every two weeks to feed 10 kids. I'm from the Bronx where I had to fight a lot because of my accent and my name. I'm from the things I remember and things I'd like to forget, and that is where I'm from.

[music]

Kai Wright: It's Notes from America. I'm Kai Wright, and welcome to the show. This winter, we had a show about the police killing of Tyre Nichols in Memphis. This was a tough conversation, as we sometimes got to have if we're going to live in a functioning democracy. I acknowledged in that show that I didn't watch the video of the officers beating Tyre.

I long ago quit watching the snuff films of the news cycle. I cannot do it anymore. Anyway, after the show, one of you left me a voicemail on our website, this listener Diapriye Kukum they said they understood, they don't watch the videos either, and then offered me some advice. Listen to this.

Diapriye Kukum: I'm 47, and so I was in my developmental years when I saw Rodney King, and I'm often taken back to Amadou Diallo. What did he do other than try to come here and live the American Dream? For me, spoken world poetry has always been an outlet for those feelings of watching and having to be exposed to these videos, and having to contend with what we tell our young people, not least with what we tell ourselves.

Kai Wright: First off, thank you for that Diapriye Kukum, but also , that advice turned to poetry. It got us thinking more broadly. Maybe poetry could facilitate some of the more challenging conversations we have on Notes from America. So many of us are struggling to hear one another, and I don't mean that in the facile terms of political punditry.

I think we've all been through a lot in recent years, and many of us just don't have the space to really take in someone else's experience. Well, Bob Holman and Steve Zeitlin have been thinking about this challenge and they've come up with something they hope will help. They're inviting everyday folks to write poems using the prompt, "I come from", and we are going to take up that prompt together this week and maybe be able to hear each other a little better.

First, let me introduce Bob and Steve. Bob Holman is a poet and filmmaker. He's the owner of the Bowery Poetry Club here in New York City, the original slam master of the Nuyorican Poets Café, and has been part of so, so many cool projects in the spoken word movement over the decades, notably including the PBS series, United States of Poetry. Bob, welcome to the show.

Bob Holman: Thanks very much, Kai. It's really good here finally to be able to pimp for an anthology-

Kai Wright: [laughs]

Bob Holman: -of the actual text, a book where people can say where they're from and how their political roots grew along with their family roots.

Kai Wright: We're going to get right to that here in a moment. Steve Zeitlin, meanwhile, who is here with Bob is the author of The Poetry of Everyday Life Storytelling and The Art of Awareness. His work is rooted in the idea that each of us have a story to tell. He's the founding director of CityLore, which I think is best described as a grassroots cultural preservation organization, and which is where Stephen Bob's poetry project got started. Steve, welcome to Notes from America.

Steve Zeitlin: Thank you.

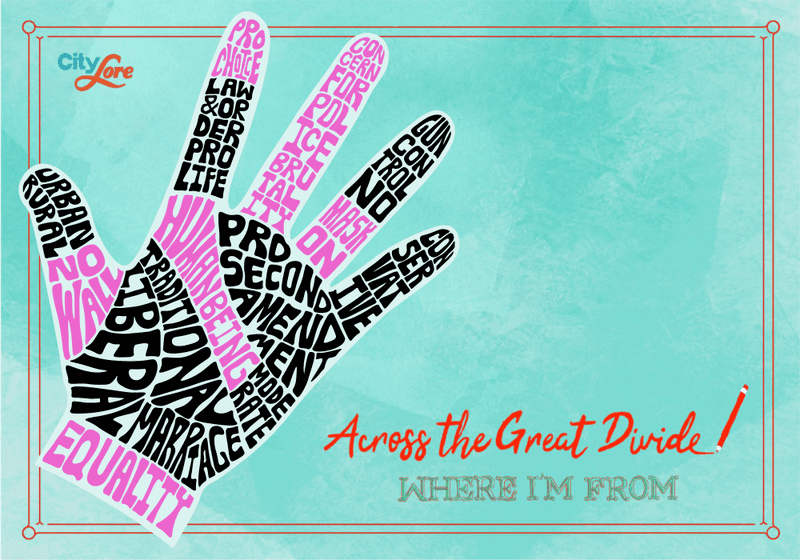

Kai Wright: Let's start, Steve, with the project the two of you have launched, it's called Across The Great Divide. As Bob has suggested, it's asking everyday people to write poems using the prompt I come from.

Steve Zeitlin: Where I'm from.

Kai Wright: The prompt, "where I'm from". That's where they got to begin and then they have to use that phrase elsewhere in the poem. What's the idea behind that specific prompt?

Steve Zeitlin: Well, George Ella Lyon, the well-known Kentucky poet wrote a poem originally called Where I'm From, which used the details-- Bob, why don't you-- you can tell how that part starts.

Bob Holman: Well, she's from Harlem in Kentucky just like me. The poem starts off, I am from Clothespins and Carbon Tetrachloride. That's because she grew up in the back of the dry cleaners store there in Harlem. It's a way to say where you're from with the details and images of your own childhood, that can now be shared with the public. It's not like a conversation where you say, oh, I was born here and moved there and did that. It's your poem, self, talking-

Kai Wright: Your poem self.

Bob Holman: -and how you got to be who you are politically. If you're going to try to cross that great divide, we think everybody started somewhere and then how did they grow? If you can tell us how you grew in your direction, maybe you'll listen to how I grew in mine.

Kai Wright: Steve, why do you think that's an effective way to start a conversation about what you're thinking politically?

Steve Zeitlin: Another thing that George Ella Lyon once said to me is, do we speak from the stances that we take or is there something deeper to us than the stances we take? Yes, part of it is, I'm a Republican, I'm a Democrat, I'm a male, I'm a female, I'm gay, I'm straight. There's an element of that about where you're from, but you're also from a very personal place.

We thought that if we could get people to combine in a poem, where they're from personally and how their politics grew, and how their family tree of politics was shaped in terms of their parents, then we can start a conversation that goes beyond just the issues that divide us and get to some of the personal elements that shaped us and gave us more of a common ground to start talking to each other.

Kai Wright: It's really interesting because on this show, we're always trying to get everybody to speak in first person. Tell us about yourself. It's the most fruitful place to begin. You're the world's expert on yourself. I love this idea.

Steve Zeitlin: Where I'm from, which is a prompt that's been used everywhere for all kinds of writing exercises all over the world at this point, is given a little bit of a different turn in what we're doing because it's not only where you're from, but also where you're from politically. We're interested in hearing all the voices. That's another title that we've been using, all the voices, to try to hear where people are from. Admittedly, people have described CityLore in the Bowery Poetry Club something as a practical application of a utopian endeavor.

[laughter]

Bob Holman: That's it.

Steve Zeitlin: We are that practical application of utopian endeavor. What we've learned in doing the project is that just giving people a chance to talk, listening to them is a sign that we are interested in what their political point of view is, even if we don't agree with it.

Kai Wright: Well, let's kick things off with one of the poems you've collected. This is a poem by an 11-year-old named Mia. She begins with the prompt of where I'm from. Here's Mia.

Mia: I come from dragging twister

Out to the back porch

And dead man come alive on the trampoline

Mommy, mommy, come alive

When I count to number 5

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, mommy, mommy come alive

Or I sit in a box and pretend to be a crazy driver

I come from the new world

I try to keep the earth beautiful

clean water, clean air

I don't want plastic them to me

Neither does the ocean

I want to be able to breathe

I want to be able to live a normal life

Adults go out of their way to make other people feel bad

Don't be sexist poop heads

Don't vote for someone who is poopy just because the other candidate is a woman, or because they wear a fish hat, fish hats are cool

Just because you look different, doesn't mean we're not the same inside

Just because you don't know, it doesn't mean you shouldn't try it

Older people don't want to change how they think

I've had this car for 19 years, I don't want a new one

But there's no trunk anymore, there's no one does anymore

Younger people, even though we might be a little weird, our minds are more adapted to the new world

What are my dreams? Parakeets.

Live in a modern ferry cottage

With internet, no people for thousands of miles, mythical and a white Jeep

Kai Wright: Mia, so I felt a little seen with this whole, like, you don't want to change your car after 19 years. It doesn't work anymore and you still want to stick to the thing that didn't work for you before.

Bob Holman: There you are.

Kai Wright: It still didn't work for you. Who is Mia? Introduce us.

Steve Zeitlin: Bob and I both have a poem that actually is a vehicle cover with poems. We took it down to the Galax Fiddler's Convention in Galax, Virginia because we know that that's a place that attracts a lot of conservatives and a lot of liberals, both, who are interested in blue art-- [crosstalk]

Bob Holman: Let's face it, Steve, I mean, poetry is something that's a pretty blue art. When you find who the pantheon of poets are, they're generally lefty activists. I think it's someplace that the right has seeded to the liberals is poetry. It's like what Sam Hamel said when he was at the Rose Garden at the White House. He said, "Poets against the war. That's like saying Generals for the war." An overwhelming number of our submissions have been from left-leaning thinkers.

Kai Wright: You went down there looking for--

Bob Holman: We went to that territory, yes. We went down to Galaxy Virginia.

Steve Zeitlin: We actually had a cranky, which is a little theatrical thing where anybody can write on and we asked them to write this, a poem on this, basically, a sheet of paper. Mia Irwin was one of those kids who came up there. She's been going to the Galaxy Film Festival with her family since she was two years old.

Kai Wright: Wow.

Steve Zeitlin: She came up and started writing this poem. We interviewed her and wrote down and took down that poem. There was a bunch of kids who contributed their poems. We thought, actually, we never thought of it before, but what are the politics of a kid?

Bob Holman: Exactly.

Kai Wright: Be kind.

Bob Holman: You talk about your utopian, the kids' habits. Steve, it was not a film festival. You lefty yourself. This was the Fiddler's Convention. It's a folk convention. That's why Mia was there. I loved the way that she put those schoolyard rhymes into her poem. We were actually surrounded by poetry, just that we'd never think of it. The lullabies that your mama sang to you are the poems. Who else could say stop the Sexist Poop Heads. Come on.

Kai Wright: We got to take a break. We're going to have a lot more of this. Listeners, we're not going to force you to write Poetry on demand, but I do offer you Bob and Steve's prompt. Call us up, start with, "where I'm from", and tell us something about your roots that informs your worldview. We're not looking for ideology here. I want to hear something specific about you. Hey, if you do have a short poem, we'll take it. Your calls and more selections from Bob Holman and Steve Zeitlin across the Great Divide Poetry Project after break.

[music]

Rahima: Hi, it's Rahima, one of the producers on Notes from America. If you called into the live show recently, you may have spoken to me. I'm the one who makes sure your audio sounds good before you go on the air. You're welcome. No worries if you haven't been able to call in yet, you can always leave us a voice note instead. Here's how. Go to Notesfromamerica.org and click on the green button that says Start Recording. We might play your note on one of our mail-back segments, or we may even build a whole show around it. All right, that's it for now. Thanks for listening.

[music]

Annie Lanzillato: I am Annie Lanzilato, and this is my poem, Voting.

I am from US of A

But our country is in a nose dive

And the only thing that keeps it from crashing is the vote

Now, my mother always took me to vote

I voted in every presidential election since 1964.

What? Yeah, I was one years old, but my mother let me pull the levers

We voted for LBJ in '64 and in '68, Humphrey

I was five years old

My mother and I walked up the poles of Zerega Avenue

Up to the poles, not hand in hand, but pinky dinky

She called it holding pinkies

And we went into the voting booth, and it was magic

She let me pull the lever and the red curtain closed behind us

I said, "Ma, this feels so private

I mean, what is it a big secret who you vote for?

Why? Like, what's going on?

Does Daddy know who you vote for?"

My mother seemed more free in the voting booth than I'd ever seen her

Because we lived in a violent dictatorship under my father

He had post-traumatic stress from hand-to-hand combat as a Marine in World War II in the battle on Okinawa

And this was acted out in the kitchen and the basement, and the garage, and every other room

And my mother, what she voted for was against war

Against killing

She voted for what she prayed for, peace

That's how she voted

And she taught me from three years old, "This is very important

And who you vote for President of United States affects millions and millions and millions of people

That you're never even going to meet

You'll never know their names

But you have to think about them."

Kai Wright: That was part of Annie Lanzilato's contribution to the Across the Great Divide Poetry Project. This is Notes From America. I'm Kai Wright, and I'm joined this week by poet and filmmaker Bob Holman, and by the founder of CityLore, Steve Zeitlin. Bob and Steve are collecting poems from everyday folks like you, dear listener. They ask contributors to begin with the prompt, where I'm from, and they hope what you say next will tell us something about the intimate, personal, real life stuff that actually shapes all of our politics.

Listeners, I am going to offer you that same prompt. Call us up, start with where I'm from, and tell us something meaningful about your life experience that informs your politics. 844-745-TALK. That's 844-745-8255. Or you can drop a few lines in the chat if you're joining us on YouTube. Again, we will take a short poem if you've got one in mind. Short is the appropriate word here. I suspect maybe we've got some slam poets like Bob out there, maybe some freestylers.

Bob Holman: Let's do it.

Kai Wright: Let's do it. Bob's eager to get it. First off, while calls are coming in, tell us more about Annie whose poem we just heard. Tell us about her. Whoever wants to go.

Steve Zeitlin: Annie is a marvel. She grew up in the Bronx, and she's never lost that Bronx stickball self. You hear it in her poetry. She's a performer in New York City. She's wonderful and you can Google her. She's a marvelous person. Also remarkably, a number of the poems that were sent in were about voting and about being a little kid, and going with your parents and being in that little booth.

Kai Wright: That's so interesting.

Steve Zeitlin: Seeing that lever pushed, and that's really democracy at work no matter who you voted for.

Kai Wright: That people have this emotional memory of that as they [unintelligible 00:17:27].

Steve Zeitlin: Exactly.

Bob Holman: Exactly. It's not unique to the United States, but it certainly is an icon here. In many countries, the voting takes place in a whole different way. You got to get your thumb painted blue and you've been-- There's a lot of different ways to vote, but the American way of voting is one of the things we can still be proud of.

Kai Wright: Can I ask you guys about just the fundamental idea here about why poetry is an effective way to communicate these ideas? What is it about this media?

Bob Holman: Listen, language is the essence of humanity and poetry is the essence of language. Somehow or other, words mean what they mean. When we call them a poem, all of a sudden it takes on-- They're saying that's what it has in my childhood was, oh, it's something that some old dead person wrote. What it's taken on now and what it has been through the years, we've only had 2,000 years of writing. We had 40,000 years of the human voice being the way that poetry was pervade.

Now, even, and here we are in this podcast doing this voice thing again. You're speaking from your heart. You're letting your voice out. These are words that you use both in the literary skills and in the orality of it. When you put it down in poetry, somehow it takes on more of a meaning. I wish more of that meaning could be amongst the whole body politic. With hip hop taking on the major voice in the world now for poetry, it's poetry that's you can dance to-

Kai Wright: That's right.

Bob Holman: -and everybody can partake so whatever your style.

Kai Wright: Let's start partaking, get some poetry from our listeners because I'll have to say, Bob, we are live on the radio, not the podcast.

[laughter]

Bob Holman: Oh, I forgot.

Kai Wright: I know it's a hard thing to remember. Live on the radio. We're going to make some poetry together. Let's go to Michelle in, I believe Teaneck, New Jersey. Michelle, welcome to the show.

Michelle: Thank you. Thank you very much for answering my call. I really appreciate all the work you've done, Kai, in these conversations and am excited to contribute today.

Kai Wright: Oh, thank you so much. I understand you may actually have a poem for us, Michelle.

Michelle: Yes. I'm driving to pick my son up from the airport and I'm listening to you and inspired me to tell you where I'm from.

Kai Wright: Please, go for it. I hope you're not actively driving in the moment, but go for it.

Michelle: Thank you.

I'm from a place where Black Excellence was excellent before we even knew the term

I'm from a place where Black Love was on display

It didn't matter who you loved, what your pronouns were, where you came from, love was all around us

I'm from a place that values the humanity we all have. I'm from a place I call home

Kai Wright: Thank you so much for that, Michelle.

Bob Holman: 10.

Kai Wright: 10. Bob gives it a 10. I love that.

Bob Holman: Come on. That is a wonderful poem, Michelle. Thank you so much. The way that you started off with references to Black Life, Black Love, to me, begins like a litany. That repetition is what turns it into a poem. Within four lines, you turned it around and just say, "Where I'm from is a place called home." That sums up the whole thing. Beautifully done.

Kai Wright: Thank you so much, Michelle. Safe travels.

Steve Zeitlin: Really, it gets both your personhood and your politics in the same poem. That's what we're looking for.

Kai Wright: Let's go to Hannah in Mound, Minnesota. Hannah, welcome to the show.

Hannah: Hi, thank you so much for having me on. Though I'm a little nervous, I just wrote this while I was listening to you, so I haven't actually spoken it aloud before, but I'm going to give it a go.

Kai Wright: Okay.

Bob Holman: Excellent.

Kai Wright: Congratulations, first off. Thank you, and let's hear it.

Hannah: Thanks. I was inspired.

I come from women who cloak their shame and pride

Women who mask the patriarchy, yes, pander to men

I am from impoverishment, hidden in cloaks of grandiosity

We had our stories that spotlight our insecurity

All that was learned where we come from, we can choose where to go, anywhere

Seeking individuality, independence, and their true authenticity

Bob Holman: Beautiful. That's plenty. Hannah-

Hannah: I think where we come from is a lot of about the people, and not the place.

Bob Holman: It sure is. That's the truth

Hannah: You can be anywhere, but it's who you're with that feeds it.

Bob Holman: Yes. You started off, Hannah. Again, like our previous caller Michelle did. By listening, a single word that came back, and that word for you was women.

Speaker 1: Women who cloak their shame and pride. What a beautiful line.

Hannah: I come from women who cloaked their shame and pride.

Women who mock the patriarchy, yes, pander

I am from impoverishment, hidden, in cloaks of grandiosity.

Bob Holman: "In cloaks of grandiosity, that is-

Hannah: Those are the veils we put up around our herself.

Kai Wright: Beautiful. We're talking a metaphoric, and magical poetry that's going on for you. You must be a poet in real life, Hannah.

Bob Holman: Thank you. Thank you so much, Hannah.

Steve Zeitlin: That's only your first draft, but we're inviting you to send your poems in as well.

Kai Wright: Already somebody on YouTube, Anna on YouTube asks, "Where do we submit these poems? Can you still submit them? Where do you submit them?" Let's hear it.

Steve Zeitlin: Yes. You can submit them. The email is poetry@citylore.org. Poetry@C-I-T-Y-L-O-R-E.O-R-G. Simple as that. We will answer everybody. We're putting together a book. If your poem is in the anthology, you'll get $50.

Bob Holman: $50 boys, come on now. That's a big pay for poetry, lad.

Kai Wright: Do you work with people when they submit them?

Steve Zeitlin: We respond to everybody, and we have been working individually with people as well. We're not on an instant timeframe either. We're putting together a book, which could take a while to finish. We want to hear from as many people as we can, and we will get back to everybody.

Kai Wright: Stephen D. on YouTube submits a haiku. I'm going to do my best to do it justice, Stephen D.

Where I'm from, people will say the nastiest things, the politest way.

[laughter]

Bob Holman: That's a great haiku. I was not able to keep up with the syllabification of that now, Kai. Is that 17 syllables?

Kai Wright: You are looking at the right guy.

Bob Holman: That's a good surprise. That's a great surprise.

Steve Zeitlin: That's really good. That's great.

Bob Holman: Read it again, please, Kai.

Kai Wright: I'm going to try.

Where I'm from, people will say the nastiest things, the politest way.

Bob Holman: You're saying a lot with a little, which is what poetry wants to do. It's language condensed in its way.

Steve Zeitlin: So much more than somebody saying, "Where I come from, everybody with so polite. It's condensed and it means so much more.

Kai Wright: It's not just something about what Steven D's politics, I think. Let's go to Erica in Saint Paul, Minnesota. Erica, welcome to the show.

Erica: Thank you. Thank you. I will read an excerpt from the, "where I'm from" prompt that I wrote back in 2020 for a Minnesota Corral Bridges project, that involves various communities. It's an excerpt. Here it goes.

I'm from the mostly biblical roster from Abraham, Sarah, Benjamin, Isaac, Sadie, and Risa

From the Rockas political fighters of the kitchen table

The laborers and floss and dough

The education is everything tribe

I'm from Rose and Louis, from rye bread and brisket

from Mid-Beach to Manhattan

From undocumented immigrants to American citizen

I am from the hope, the longing to strength, the survival of all those who came from other lands to make me American.

That's my excerpt.

Kai Wright: Thank you so much, Erica.

Bob Holman: A country of immigrants, and Erica is going back into her roots. I love a way she brings up everything is an education. That was her family, sitting around the kitchen, the Rockas kitchen table. This is where so much politics begins, and we don't get back there enough.

Steve Zeitlin: Let me ask you if it's biblical on top of that, if it's biblical.

[laughter]

Kai Wright: Perhaps some of the first written poetry, perhaps. Talk to me about some of the poems? You said, yes, it's a blue, as you put it, Bobby, a blue art form. Nonetheless, you've sought out people with a range of political ideas for this. Tell me about the folks you hear from where you're like, "Oh, this is hard for me. This poem is, I'm not sure I believe in what they're trying to articulate."

Bob Holman: Let me read you this poem we got from Mr. Anonymous. Is that all right?

Kai Wright: Yes. Keeping in mind, we're live on the radio. I don't know what you're doing.

Bob Holman: I'm not going to use the f word.

Kai Wright: All right, thank you.

Bob Holman: I am going to say "F word."

I am from F*** for me first thing in the morning

I am from the A***hole of the country, but somehow I am the happiest guy I know

I'm from living on his own terms

I'm from four kids, all great

I worked for the kids

Two boys here working, two girls going for their masters

I'm from I can't get it

I'm from I'm going to get it

I'm from I couldn't get into med school, so I got into trucks

My buddy and I started this place with wrenches and a little talk, and that's about it

We've been doing it ever since

I am from hard work and be honest

I don't vote Republican, I vote for the right guy

I'm from having a loaded licensed gun in my pocket, as I do right now

I'm from wanting to know your business plan

I'm for what the country needs

I am for something working

If this poem could work, then I'm from poetry.

Steve Zeitlin: "If this poem can work, I'm from poetry."

Kai Wright: Why do you share that one, Bob? Why don't you just tell us about that piece.

Bob Holman: This gentleman was a Trumper. There's no doubt about it. The place was festooned with it. Yet he's able to also give his family-- What he's working for? Yes, he's working for these ideas of an iconic classic in his terms, president, but he's also working for his family. Aren't we all? It was a surprise to me that he had a gun in his pocket. That's this world that we live in.

That should be there just as he had, I don't know whether it was courage or bravado. I don't know if it was really true. That is America too, and that's why let's listen to this voice and-- I don't know if understand is the right word, but let's communicate.

Kai Wright: We're going to have to wrap up soon. We got a lot of folks we weren't able to get to. If people want to continue to participate in this, let's remind people how they're going to be able to do it. What do they do? What's going to happen when they send a poem to you? How do they be part of this?

Steve Zeitlin: Okay. Well, they just have to send it to poetry@citylore.org CityLore C-I-T-Y-L-O-R-E.org. We do answer everybody. We've oftentimes gotten back to people and suggested edits for their poem and things like that. We're gradually working towards both a film and a book that would hopefully open a dialogue. We feel like even listening to people from lots of different perspectives, is part of what we're trying to accomplish.

Because a lot of times, the conservative people like the person whose poem he read, he said this to us, we wrote it down. We showed it to him, and it became a poem. It kind of in the making, it moves from an ideology to poetry.

Kai Wright: We've got to wrap it up. Steve Zeitlin is the author of The Poetry of Everyday Life: Storytelling and the Art of Awareness and the founder of CityLore. Bob Holman is a poet and filmmaker, and the owner of the Bowery Poetry Club in New York. Thanks to you both.

Notes from America is a production of WNYC Studios. Follow us wherever you get your podcasts and on Instagram @noteswithkai. Mixing and theme music by Jared Paul. Milton Ruiz was our live engineer this week.

Recording, producing, and editing by Karen Frillman, Vanessa Handy, Regina de Heer, Rahima Nasa, Kousha Navidar, and Lindsay Foster Thomas. André Robert Lee is our executive producer and I am Kai Wright. Thanks for spending time with us.

[music]

[00:32:02] [END OF AUDIO]

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.