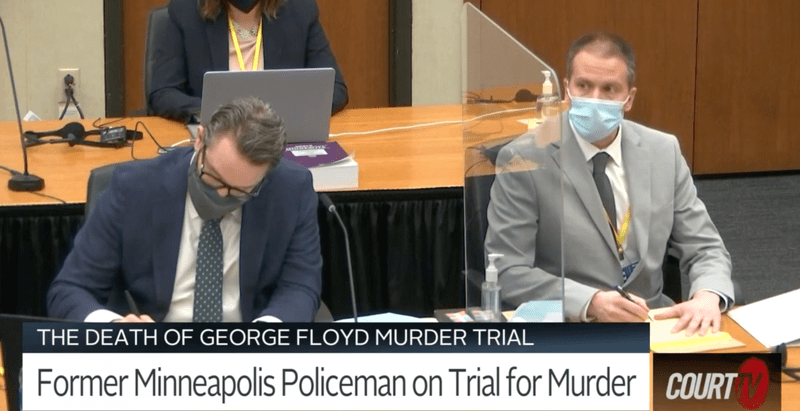

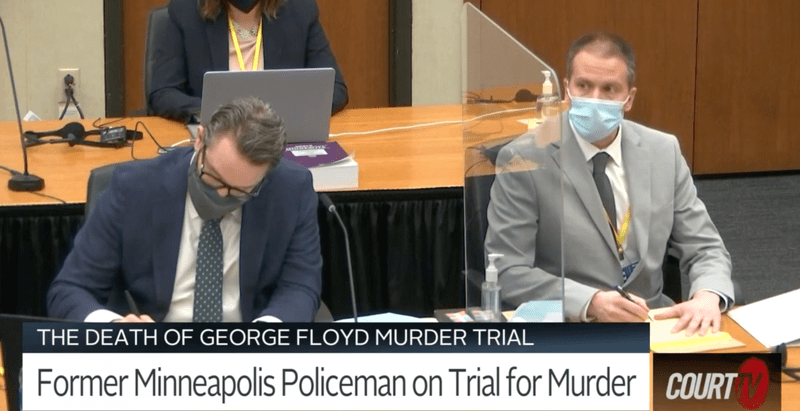

BROOKE GLADSTONE From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media, Bob Garfield is out this week, I'm Brooke Gladstone. It's been 10 months since former police officer Derek Chauvin was captured on video with his knee on the neck of George Floyd. Who died pleading for his life in what the county coroner determined was homicide. This week, Chauvin sat on trial for multiple charges, including third degree murder. In the courtroom, he locked eyes with several witnesses he has not likely seen since that fateful day, May 25th, 2020. First responders, teenagers with cameras and cries, passersby trying to intervene, and the young grocery store cashier who confronted Floyd about using a counterfeit bill. The testimonies were studded with sorrow and guilt.

[CLIP]

WITNESS It's been nights. I stayed up apologizing and apologizing to George Floyd for not doing more. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE The decision to televise these wrenching testimonies was a rare exception to a law prohibiting cameras in Minnesota courtrooms. Writing in The Washington Post, entertainment business reporter Steven Zeitchik explains how Court TV became the world's window into the trial and how the controversial but largely forgotten legal affairs network is using it to make a comeback and also, it says, to bring transparency to the criminal justice system. Steven, welcome to the show.

STEVEN ZEITCHIK Thank you for having me.

BROOKE GLADSTONE In its heyday, Oprah Winfrey described Court TV as the hottest soap going filled with murder, nasty divorce, nail biting suspense. And it turned witnesses and prosecutors and defense attorneys into celebrities.

STEVEN ZEITCHIK Of course, they hit their heyday with the O.J. Simpson trial back in the fall of 1995. Must see TV from Barry Scheck, the DNA expert, to Lance Ito, the judge to, of course, Johnnie Cochran, the defense attorney.

[CLIP]

COCHRAN You look at O.J. Simpson over there, and he has a rather large head, O.J. Simpson in a knit cap from two blocks away, is still O.J. Simpson. It's no disguise, it makes no sense, it doesn't fit, if it doesn't fit, you must acquit. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE In '92, the network reported on Jeffrey Dahmer's trial. That was particularly gruesome, it was about cannibalism and serial murder.

STEVEN ZEITCHIK Yeah, the Dahmer trial was definitely an early entree into the form for them at the very tabloid end of the spectrum. They also had the trial, the officers accused in the beating of Rodney King in Southern California. That was a more serious foray into criminal proceedings.

[CLIP]

PROSECUTION Also during the tape, you're going to see, while Mr. King is on the ground lying on his stomach as his hands are moving back toward putting them behind his back, Officer Briseno walks over and delivers a stomp to the head and neck area of Mr. King. [END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE Court TV disappeared for a decade up until a couple of years ago when it was picked up by the E.W. Scripps Company, it's the big news conglomerate, and the network saw the Derek Chauvin trial as the big comeback opportunity. How did the network convince Judge Peter Cahill to give it exclusive filming rights?

STEVEN ZEITCHIK Court TV did not make a formal argument. They were working behind the scenes. The defense ultimately is who filed the motion. The argument was that Derek Chauvin is entitled to a public trial, and in the time of Coronavirus and Lockdowns, that is going to be severely compromised because people can't come into the courtroom as they please, as they would in a normal time.

BROOKE GLADSTONE I thought that typically live TV coverage of murder trials hurts the defense.

STEVEN ZEITCHIK You're exactly right, and I think there are a lot of theories for that. That it can really hurt their case if the crime and the victims are seen in full relief. One person I talked to offered an interesting theory that because the death of George Floyd was so visible and was seen by so many people around the world that there was nothing that the defense felt could be lost from seeing this reenacted. Maybe they had something to gain, in fact, by showing Chauvin and maybe trying to humanize him, which, of course, is typically a defense strategy. So I think we can only speculate on that, but that was one theory that was offered.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Could you summarize quickly the restrictions the judge placed on the cameras of Court TV, that may have the effect of making the broadcast less tabloidy?

STEVEN ZEITCHIK He did allow three cameras in the courtroom. Listeners may remember O.J. only had one, but one big restriction he did put on the cameras was he did not allow them to zoom. So anyone who's seen the trial will basically notice that if they're watching the witness stand or anything else, they're seeing it from one distance point, but not anything further. Another restriction we put on is who can be shown. He is not allowing any members of George Floyds family to be shown in the gallery. And if the camera could zoom and capture that, that tends to heighten the drama and potentially heighten the soapiness affect.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Court TV ultimately will deliver a rich document for historians and journalists, but not everyone you spoke to bought the idea that criminal justice transparency is really Court TV's goal. Obviously, it's a business, these cases are a big part of their product. In fact, Todd Boyd, professor of race and popular culture at the University of Southern California, told you that the notion of bringing transparency to the criminal justice system is bull.

STEVEN ZEITCHIK If something is happening behind closed doors, there's a natural skepticism about whether what was happening there was fair. When it's more out in the open, when there are cameras, that tends to make us believe that everything was fair. That tends to reduce our skepticism about the system and about the process. And I think what he was really kind of warning against was that let's not let the fact that there are cameras here allow us to lower our guard about potential unfairness in the system to people of color. That's what he was warning against.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Steven Zeitchik is an entertainment business writer at The Washington Post. Thank you very much.

STEVEN ZEITCHIK Thank you so much for having me.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.