The Supreme Court v. Peyote

Julia Longoria: I'm Julia Longoria. This is More Perfect.

The first time I ever walked into the Supreme Court, it kinda felt like church.

You walk through oversized doors into a hall of white marble with high arched ceilings. People speak to each other in hushed tones, awaiting the words of nine civil servants in robes, who strive to answer to a higher power of sorts — the law. Over the last few years, a number of religious people have been trying to tell the Supreme Court that their god puts them above the law.

[Archive Clip, News footage]: A clear win for Jack Phillips of Denver, who said baking a cake for a same-sex couple would violate his Christian beliefs.

[Archive Clip, News footage]: The Supreme Court saying that Catholic organizations do not have to comply with these anti-discrimination laws.

[Archive Clip, News footage]: This is a big legal cause of conservatives in America, which is telling religious institutions and religious people that they don't have to follow the laws that everyone else has to follow.

Julia: Just this term, they accepted another case where a Christian wedding website designer is asking the Court if she can duck an anti-discrimination law and deny her services to same-sex couples.

Over and over the Court keeps taking on this same kind of case and saying: yeah, it’s okay if you sidestep the law. But just this one time. They stop short of making a sweeping statement about our freedom to do that.

The last time they made a sweeping statement about our right to freely exercise our religion, it was not pretty.

People across the political spectrum criticized the Court for weakening our First Amendment.

It was in 1990 and it involved a man named Al Smith.

Electronic Voice: Thank you for parking with the Eugene Airport.

Garrett Epps: Shut up your face.

Julia: This man is not Al Smith.

Julia: Just so I have it on tape, can you say just who you are?

Garrett Epps: Yeah, I'm Garrett Epps and I teach constitutional law at the University of Oregon.

Julia: When I was looking into Al Smith’s very controversial case, everybody told me: you gotta talk to Garrett Epps.

Garrett Epps: Uh, I had the great good luck, uh, quarter century ago to meet and interview Smith.

Julia: Al Smith died in 2014. But much of the drama of his case — where he broke a state drug law, for religious purposes — took place in Oregon, where Garrett Epps lives.

Julia: I can't thank you enough for picking me up at the airport.

Garrett Epps: I'm so excited.

Julia: You’ve been waiting.

Garrett Epps: I have, yeah.

Julia: For a scholar of the law, Garrett had an unusually intimate look into the personal drama behind this case. He still remembers the first time he met Al Smith.

Garrett Epps: It was quite dramatic. My son was at Roosevelt Middle School here in Eugene. They had a thing called the cultural heritage fair. And every sixth grader does a little poster about what they consider to be their cultural heritage. It’s fascinating to see what they pick.

Julia: Garrett says he was walking around the fair. One kid did a poster on the gold miners in her family. There was his son’s poster about their family’s five generations of lawyers.

Garrett Epps: And and uh, there was this booth with this distinguished looking, very impressive old man, sitting in a chair. He is the poster, right? The living human being. This young girl, she said, this is my father, Al Smith.

Julia: Everybody brought posters and you brought your dad?

Ka’ila Farrell Smith: I would do that. Yeah I would definitely, I’d like, Dad, come on, there's a school thing.

Julia: That girl was Ka’ila Farrell Smith, Al's daughter. She still lives in the area.

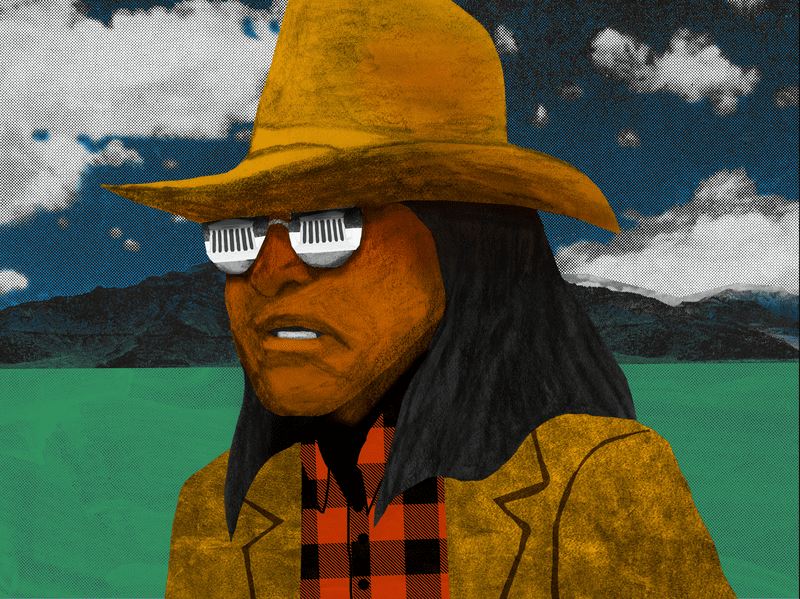

Ka’ila Farrell Smith: He was a very dark-skinned man. Long black hair, you know, he always had his cowboy hat, he kind of got into the super Indian look. People were proud to be Indians again. And then he always had these red Nikes, like high tops.

Julia: Al Smith used to joke about how he didn’t have an Indian name. Ka’ila says when he’d go out to eat, he’d reserve a table under a fake name.

Ka’ila Farrell Smith: He would always write down Red Coyote. People would be, oh, Red Coyote. And they'd look up and, oh, this Indian guy would walk by. And that was his thing. And it was just like a way to like mess with people, I guess.

Julia: It was like giving the people what they wanted,

Ka’ila Farrell Smith: What they wanted, like a spectator thing.

Julia: Al spent his life searching for an authentic way to practice his own Native traditions. And that was hard because he’d been cut off from them as a kid.

Ka’ila Farrell Smith: He wasn't really raised around Native culture and ceremonies, and that's kind of how he told his story. But by the time I was born, it was 100% like his life.

Julia: This week on More Perfect, we tell the story of Smith. Al Smith.

Galen Black: He had that humor that could take you out of depression in a heartbeat.

Julia: The remarkable and complicated man.

Ka’ila Farrell Smith: He was definitely, like, combative, but like in his own way.

Julia: And Smith, the Supreme Court Decision that so many people love to hate.

Garrett Epps: And, you know, I wanted, I have wanted. I spent years wanting Smith to be overturned, right? Be careful what you wish for.

THEME: OYEZ

Jane Farrell: Good. So nice to meet you. Come on in.

Julia: Oh, it smells so nice in here. Should I take my shoes off?

Jane Farrell: Yeah, that’d be great.

Julia: Sage had been burning at Al Smith’s house when I got there.

Jane Farrell: I'm Jane Farrell and I was married to Al Smith for 35 years, and we have two children together.

Julia: I picked up Al’s widow Jane in my rental car and we met up with their daughter Kai’la …

Ka’ila Farrell Smith: So this is it. This was all my family's land that was sold.

Julia: … for a tour of Al’s ancestral homelands. It’s now southern Oregon. And it no longer belongs to the Klamath people. They were one of 109 tribes that were “terminated.”.

The U.S. government at one point wanted to assimilate tribes that were quote “ready” for that. So in 1954, it stopped recognizing the Klamaths, sold off their tribal lands, sent them a check. Federal recognition was eventually restored in the ’80s. And recently, Ka’ila bought property nearby.

Jane Farrell: There's Mr. Smith.

Julia: They took me to Al Smith's grave.

Ka’ila Farrell Smith: I hate this grass

Julia: which was overgrown with weeds.

Ka’ila Farrell Smith: This cow grass. It's not native.

Jane Farrell: I don't feel like the writing is really holding up on this marble, you know?

Julia: We could barely make out the words on his tombstone.

Jane Farrell: So gosh, it’s not, it's not, not legible.

Julia: This is a man whose name is repeated over and over in the mouths of lawyers and Supreme Court justices. But in court records, Smith — the decision — is completely divorced from Al Smith and the life he lived.

Jane Farrell: Alfred Leo Smith. November 6th, 1919. November 14th…

Julia: Al Smith was born on a little patch of green along a riverbed. At his grandma’s house. The soundtrack to his childhood on tribal land was oars paddling on the Williamson River, the bark of his dog, and at night, the sounds of his grandma praying.

I know this because of Garrett Epps.

Garrett Epps: Here, a feast of minidiscs. Take a look.

Julia: He had the foresight to record his conversations with Al, on now obsolete minidiscs.

Julia: Here we go. Al Smith, 6-21-95.

Archive Clip, Al Smith: I can remember my grandma used to pray in Indian every night.

Archive Clip, Garrett Epps: You didn't know what she was saying...

Archive Clip, Al Smith: No!

Julia: Al never learned what her prayers meant in the Klamath language. Because at about age 7, he was taken from his tribal home and sent to a series of Catholic boarding schools. This was part of a concerted effort by the U.S. government to get Native children “ready” for assimilation by cutting them off from their Native traditions. Many of these boarding schools were notorious for sexual and physical abuse.

Jane Farrell: I mean, he was the little boy who got his fingers scrubbed ’till they bled and you know, was beaten. And sure, they were very cruel. And that was the point where he would describe in many of his stories that you can hear where he would say, I learned about high fences …

Archive Clip, Al Smith: I remember high fences, cement yards.

Jane Farrell: … and cement yards.

Archive Clip, Al Smith: These huge buildings that I had to live in.

Jane Farrell: And he lost his freedom. I mean, he recognized that, that there was that moment where he lost it. It gets me a little teary.

Archive Clip, Garrett Epps: But you obviously didn't like it because you ran away. You just told me three times?

Archive Clip, Al Smith: Or more. I started running away, I guess, fourth grade, maybe. I walked on the railroad tracks waiting for a train to come by. So we'd catch it.

Julia: By the time he finally did escape boarding school, he was already a teenager.

Archive Clip, Al Smith: High school was, like, kind of the beginning then of alcohol.

Julia: Alcohol, after a childhood spent shut away from his culture, he was back in a home that now might’ve felt foreign to him. He drank through high school. One day he got into a bar fight, ended up in jail for 90 days. And caught a freight train to Portland.

Archive Clip, Garrett Epps: And how did you live? You, did you work day jobs or …

Archive Clip, Al Smith: Oh, no.

Archive Clip, Garrett Epps: Panhandling?

Archive Clip, Al Smith: Panhandling. Robbing. Stealing.

Archive Clip, Garrett Epps: Tough, tough life, huh?

Archive Clip, Al Smith: It was kind of fun.

Julia: He kept drinking when he was drafted into WWII. At bootcamp in the Jim Crow South, Jane says he was forced to drink from Black-only water fountains because of his dark skin. He then drank while on duty.

Jane Farrell: And they said, you know, Mr. Smith, I think you might be an alcoholic. He said he'd never heard the word before.

Julia: By 1957, Al was back on the West Coast drinking again, living on the streets of Sacramento.

Jane Farrell: He was very sick, you know, and dying. He felt like that was his moment. Rock bottom. And he said, he literally had had a vision and this little man had appeared to him.

Julia: It was almost like a divine messenger.

Jane Farrell: This little man said, if you don't stop drinking, you're gonna die.

Archive Clip, Al Smith: So I just flopped over and just started to sweat it out.

Julia: Al made his way back to Oregon, and started going to Alcoholics Anonymous meetings.

Archive Clip, Al Smith: I got around to taking a look at the 12 steps.

Julia: And whenegot to Step 3 of the 12 Steps: “make a decision to turn our will and life over to the care of God,” his mind went first to the Catholic boarding school god.

Archive Clip, Al Smith: Screw that God, you know?

Archive Clip, Garrett Epps: Yeah.

Archive Clip, Al Smith: But I'll try to remember my grandmother's God.

Archive Clip, Garrett Epps: Yeah.

Archive Clip, Al Smith: That'll be my God. God that I didn't understand. So that was the beginning of the change in my life.

Archive Clip, Garrett Epps: Yeah.

Archive Clip, Al Smith: I had to learn to live all over again and how to behave different. How to treat people, how to treat myself and it's a whole new ball game.

Julia: Rediscovering his grandmother’s God through AA changed Al’s life.

Jane Farrell: And his story was so compelling, he was asked to speak at AA meetings and he became “Indian Al.”

Julia: In the 1970s Al began to make a name for himself helping other Native people find sobriety. He traveled the entire country.

Jane Farrell: He took a job with the Alcohol and Drug Commission, traveled to different tribes, talking with tribal council about alcoholism.

Julia: And in the process, he was introduced to a wide array of tribal ceremonies.

Jane Farrell: So he would ask clients, you know, well, you're not a Christian. What, what are your ways, what are your ceremonies? How do you relate to the God that you understand?

Julia: Ceremonies that U.S. policy had tried to erase when they were placing Native kids in boarding schools.

Jane Farrell: We go to Sundance you know, we do sweats or they would say, I'm a Native American Church member. And that was where he had first run into the Native American Church.

Julia: The Native American Church is a decentralized, indigenous religion, practiced in different ways across different tribes. But the defining feature of the church is its sacrament.

Jane Farrell: When he was invited to this ceremony, you know, it was a dilemma for him. Because of the peyote.

Julia: Peyote, the cactus plant with hallucinogenic properties. At ceremony, believers take a small button or two of peyote.

Archive Clip, Al Smith: I got years and years and years of sobriety. Right. I'm not about to mess with that man, you know.

Jane Farrell: He took his sobriety very, very seriously and never did not chippy around. I mean, Al was clean and sober. I'm telling you. No cannabis, no, no nothing. Right? He wouldn't even take a vitamin. I mean, he didn't he didn't take pharmaceuticals. Like, Al, he was clean.

Julia: Al, informed by his addiction and the tenets of AA, saw peyote as a drug. On top of that, from what we can tell, the Native American Church wasn’t part of Al’s family’s traditions.

Jane Farrell: He was always merely a guest. I'm a guest. I'm an honored guest in these ceremonies, but I don't have my own ceremonies Like he, he never felt authentic enough. Questioning that this was something that was rightfully his.

Julia: Al struggled with this decision.

Jane Farrell: He went through a lot of, you know, mental gymnastics, you know, having to think about this and talk to a lot of people.

Julia: He talked to Native American elders. Talked to friends. They told him it’s not that kind of a drug. It’s a medicine that could be a part of his life’s healing. Peyote is believed to be the flesh of God that allows you to talk to Creator directly.

And even if wasn’t his grandmother’s god exactly, it felt more authentic to him than anything else he’d come across.

Jack Lawson: The ritual, uh, all, everything, the songs …

Julia: Al’s friend Jack Lawson was there the night he ate peyote.

Jack Lawson: … staff and rattles and people are singing, and it's an all-night ceremony. It's beautiful.

Jack Lawson: And they made Al the Cedar Man, which is a primary role within the meeting itself. And it was just like he belonged there.

Julia: This was around the first time Jane and Al met, near Klamath lands in Oregon. They fell in love, got married. Eventually, had a kid.

Farrell Smith: Oh, here, I'll show you a drawing. Hold on.

Julia: Ka'ila

Ka’ila Farrell Smith: This is a drawing I did.

Julia: Oh my God, this is amazing.

Julia: Ka’ila's actually an artist and she got her start very early, drawing portraits of her dad.

Ka’ila Farrell Smith: He has gray pants. It's definitely a stick shift car ’cause you can see all three of the pedals, he's got his driving gloves on.

He would show up looking great and then he'd find guys, you know, hung over on the street, he'd pick you up and buy you lunch. So that's where a lot of people are like to this day, like, oh, Al like saved my life. Like that's, I mean that's just, people talk about him like that.

Julia: Al was a relatively new dad to Ka’ila when he took a new job at a recovery center in southern Oregon. Unlike his previous work with tribes around the country, this time, Jane says, he’d be the only Indian counselor.

Jane Farrell: I'll never forget, new job, set your desk up. He puts all his little pencils and pens and, you know. And we took a big Pendleton blanket and put it up on the wall, beautiful royal blue. And he's gonna smudge his new office.

So he burnt some sage and it's sort of like you fresh the air and clean and bring in, you know, good energy. So he gets a little lighter there, gets it going, smoking, smoking it, getting that smudge going, cleaning the room. And all of a sudden the entire fire system alarms go off in this building. And they come rushing in. And it was this, the first cultural — what do you call this?

Julia: A clash?

Jane Farrell: A cultural clash. they were literally like, what the heck? Like I think they actually thought he was up there smoking or maybe.

Julia: Smoking weed?

Jane Farrell: Smoking weed, Yeah. And so, okay, well we have to, he had to explain, you know, it's, don't get upset, it's just some sage. This is what we do. Well you can't do it in here because there's fire alarms. Okay. Uh, got it. Won't do that again.

And that was when we met Galen Black.

Julia: Galen Black was one of Al’s new colleagues at his new job.

Julia: Wait, are you Galen?

Julia: Galen, hi…

Julia: Black is a warm white guy in his 70s.

Julia: Can I shake your hand? Oh, thanks.

Galen Black: I'm a hugger.

Julia: Also a hugger.

Julia: amazing.

Julia: Al and Black become friendly. Al invites him over to the house, and Black starts to learn more about Al’s experiences with the Native American Church.

Archive Clip, Al Smith: Galen was, uh, really interested. And so we talked quite a bit about Native American culture and spirituality.

Julia: There was a meeting coming up and Black asked if he could go. Al got sick and ended up not being able to go with him.

Galen Black: He said, why don't you go, I bet you'll learn something.

Julia: So Black went. He told me he went as a guest. He thought of it like professional development for his job counseling Native people struggling with addiction.

Galen Black: So as the ceremony progressed, I took that little bitty pencil size, eraser size, and I prayed, you know, help teach me, help, help me open my mind up so I can help others in, in this treatment. And low and behold, that's exactly what I got.

I felt an instant solid connection with everybody in that ceremony. My heart was opening up, my heart was learning new things. My heart was becoming more happy. And it was something I had never experienced before.

I had went back and talked to one of the other employees about how great this was of an experience.

Julia: And that became a problem. Word was spreading around the office that this drug and alcohol counselor was going out into the woods and taking illegal drugs.

Galen Black: And my bosses told me that I had two options, you know, well, three options. Quit, be fired, or go to treatment. I said, what am I gonna go to treatment for? You're out there chipping, you're out there chipping away using drugs, and as a counselor, you shouldn't be doing that.

Julia: And just like that, Black was fired. A little while later, as another peyote meeting was in the works, Al’s boss gives him a warning.

Archive Clip, Al Smith: He advised me not to take any peyote. Well, who the hell are you to tell me I can't go? Then I had the damn balls to, to stand up and say in a sober, sober way, screw you. So I went and ate a lot of peyote.

Jane Farrell: I remember it was over in the coastal hills here, you know, they put up a teepee and it was a, it was a beautiful ceremony that night.

Julia: You were there?

Jane Farrell: Uhhuh, I was there and Ka’ila was a baby. She slept in the back. When we brought young children in, we would kind of bed 'em down behind us in their woolies and sleeping bags. And then the children just sleep all night, you know, while the adults sit up, pray and sing.

So the ceremony was over. That was a Saturday night, and then of course, Sunday was rest day, and then Monday he went to work.

Julia: And his boss asks him, did you take any peyote?

Archive Clip, Al Smith: Well, I took the sacred sacrament, prayed for you, with the rest of you sick mothers, and I got fired.

Jane Farrell: And he literally came home Monday evening with his little box, with that Pendleton blanket off the wall, and that was it. He's done, he’s fired. And here we are, we got rent to pay.

Julia: What happened next is the crux of Employment Division v. Smith, the case that went to the Supreme Court. Al and Galen Black wanted to collect unemployment benefits and Oregon’s employment division is like “No. You got fired for work-related misconduct – taking illegal drugs. Request denied.”

Jane Farrell: It's shocking, really. We have this Constitution, we have these protections. There's these First Amendments, freedom of religion, freedom of speech, right? It doesn't take a law degree to know in the United States, you just don't tell people we're gonna, uh, fire you for going to your church.

Julia: Fired for going church? Then the state of Oregon just says sorry, you’re out of luck? Isn’t the First Amendment of the Constitution supposed to protect your free exercise of religion? The answer was a little unclear. It turns out our government has a bit of a sordid history with the First Amendment.

Garrett Epps: We have a lot of episodes of state governments and local governments, you know, doing hideous things to religious minorities, including driving the Mormon people basically out of the border of the United States.

Julia: That’s professor Garrett Epps again. For the first 150 years or so of the First Amendment's existence it didn’t do much to protect religious people, especially religious minorities. When they sued, courts would most often say: you’re out of luck. Until the 1960s.

That’s when the Supreme Court added some real oomph to the First Amendment’s right to freely exercise your religion. They turned it into a shield to protect religious people, through a case called Sherbert. Named for Adele Sherbert.

Garrett Epps: Adele Sherbet had a job in a textile factory in South Carolina. The boss told her they were gonna have Saturday shifts. And she said, well, I'm a Seventh Day Adventist, I can't work.

Julia: For Seventh Day Adventists, church is on Saturday.

Garrett Epps: And he said, well, then you're fired.

Julia: And just like Al, Adele asked for unemployment benefits after she got fired for choosing church.

Garrett Epps: And they went to the Supreme Court.

Julia: And the Court sided with Adele Sherbert. Now, If a government wanted to violate your First Amendment right to freely exercise your religion, they were going to have to have a very compelling reason to break through the new Sherbert shield. Compelling — like saving lives.

Garrett Epps: You know, like, we have to move everybody out of this area because the wildfire’s coming in. Well, my religion says I have to stay here and burn. Tough. You're out, right? It has to be that important and this has to be the only way, basically, the only way to, to make that happen, right? Uh, otherwise you gotta find a way to accommodate everybody. And that’s called the Sherbert Test.

Julia: The Court went ahead and named it after Adele Sherbert — whose life, I'm sure — would fill a different episode of More Perfect.

Back to Al Smith. The question here was could Oregon pass the Sherbert Test? Did Oregon have a compelling reason?

Jane Farrell: This compelling interest so great, so great that we need to throw this man under the bus.

Julia: So in order to force the state to pay him unemployment benefits, Al decides to sue and his case keeps getting appealed. He won in the Oregon Supreme Court and then it was time to argue in front of the U.S. Supreme Court. It was just a few days before Al, Jane and their kids were set to get on a plane to D.C. that they started getting mysterious phone calls in the middle of the night.

Jane Farrell: If you can imagine these little voices coming through, like is Al Smith there?

Julia: Leaders from the Native American Church were calling in from around the country.

Jane Farrell: They'd all kind of say the same thing. You know, just don't hurt our church. Pleading with him.

Julia: These Church elders were asking Al over the phone to drop his Supreme Court case.

Jane Farrell: And Al was just pacing. I have never, he was not someone who I would call anxious or, um, fret-ty, you know, he wasn't a fretting type.

Julia: Why would they want him to drop his case? Wouldn’t they want Al to fight for the sacred medicine?

Steven Moore: The U.S. Supreme Court had become a very dangerous place for all rights of indigenous peoples.

Julia: This is Steven Moore.

Steven Moore: Longtime senior staff attorney at the Native American Rights Fund.

Julia: NARF represented Church leaders in 1989. Steven told me of course his clients wanted to protect peyote, but they had seen the court fail to protect Native rights in other recent cases, and they thought the best way to protect the sacred medicine was to keep the Supreme Court’s paws off of it.

Steve Moore: We were concerned that Al was really, rolling the dice on, on important issues that affected, you know, a quarter of a million Native Americans.

Julia: They thought Al was going to lose. And feared this one person could end their entire religion. Because peyote existed in a legal gray area at the time. And If the Supreme Court told Al the First Amendment didn’t protect his religious right to peyote that could have ripple effects. Other state and local governments around the country would have a green light to crack down on the ceremonies of the Native American Church.

So Steve and NARF had come up with a creative solution: Let’s just call the whole thing off. It turns out, if both parties to a case on the Supreme Court’s docket settle out of court, the Court can’t hear the case and they can’t write a decision.

Steven Moore: NARF actually was involved in creating something called the Supreme Court Project, to convince people to stay away from the Court if the broader consensus is that it's the particular issues in a case are dangerous and could be lost.

Julia: NARF negotiated a settlement with Oregon’s Attorney General. The only thing Al needed to do was give up his win in the lower courts and give up his unemployment benefits.

But this was all very confusing and overwhelming to Al.

Jane Farrell: So it was very, very concerning to me the state that he was in. This brought up for him again, his insecurity, that he didn't feel he had a rightful place to represent the church. Very, very painful time.

Steven Moore: I feel very strongly that we were very transparent with Al and Jane. We told them what we were doing and they were fine with it.

Julia: I let Steve know that they were not exactly fine with it.

Julia: …very different ideas of what happened.

Steven Moore: Well, it's, it's, um, what I will say, human communication is a very difficult art. A couple nights ago, I didn't sleep for several hours and I told my wife, I said, you know, Julia is causing me to go back and process a lot of feelings. There were a lot of hurt feelings in Indian Country. I think it shocked the conscience of a lot of Native American Church leaders. Who is this Al Smith and what is he doing?

Julia: For Al it came down to a decision of whether or not to sign a piece of paper.

Archive Clip, Al Smith: So I came on home and talked to Jane and some people about, you know, what to do. And of course they just said, well, it's your decision, you decide what you have to do. In the wee hours in the morning here, it was like it came to me. It's like, uh, your kids, the kids are gonna grow up and the case is gonna come up one of these days and say, your dad Al Smith, oh, he's the guy that sold out. I'm not gonna lay that on my kids. They're not gonna have my kids, you know, feel ashamed. Even if we lose the case, you know, they're gonna say, yeah, my dad stood up for what he thought was right. So I got a couple hours sleep and phoned the attorney and told him, I says, well, let's go to court. Then we, you know, we went to Washington, D.C.

Archive Clip, Garrett Epps: Mm-hmm.

Julia: Al and Jane and the kids went along with many Native Americans.

Archive Clip, Garrett Epps: What's it like to sit there, you know, and watch the Supreme Court debate with your lawyer or with the other lawyer about your case?

Archive Clip, Al Smith: Well, you're a bump on the log.

Julia: Al sat through the whole thing.

Archive Clip, Al Smith: Got a certain little section they set you in and you sit there. And they sit up there and, uh, perform.

Archive Clip, Supreme Court: We'll hear argument next. Number 88 12 13 Employment Division of Oregon versus Alfred Smith.

Archive Clip, David Frohnmayer: Thank you, Mr. Chief Justice. And may it please the court.

Julia: They had Oregon's lawyer, the attorney general go first.

Archive Clip, David Frohnmayer: Government's interest in controlling peyote in similar hallucinogens is real. It is compelling and …

Julia: His job is to lay out the compelling state interest that Oregon had for denying Al Smith his benefits.

Archive Clip, David Frohnmayer: …to further the health and safety interests of its citizens.

Julia: He said, peyote is dangerous to the people of Oregon. The feds had labeled it a Schedule 1 substance at the time for a reason.

Archive Clip, David Frohnmayer: Peyote is unquestionably a dangerous and powerful hallucinogen.

Julia: Plus, law enforcement can't play favorites with one religion over another. Justice Anotinin Scalia chimed in on this.

Archive Clip, Justice Scalia: There is a problem in just allowing all religions to use peyote, but not allowing, uh, all religions to use marijuana.

Julia: What about marijuana religions? LSD religions? The attorney general said, look, you have to be able to create a general rule, with no exceptions, that everyone has to follow.

This is when Justice John Paul Stevens pipes up.

Archive Clip, Justice Stevens: Your, your flat rule, uh, position would permit a state to outlaw totally the use of alcohol, including wine in religious ceremonies.

Julia: What about wine at Catholic Mass?

Archive Clip, David Frohnmayer: That's a different question.

Archive Clip, Justice Stevens: Why is that different?

Archive Clip, David Frohnmayer: The issue of sacramental wine is different because, at least at the present, it is not a schedule one substance.

Archive Clip, Justice Stevens: So you mean it's just a, a better known religion?

Archive Clip, David Frohnmayer: No.

Julia: The difference, Oregon's lawyer says, is that you don't drink wine at mass to get drunk. But you do ingest peyote for its hallucinogenic effect.

Archive Clip, Justice Rehnquist: Uh, Mr. Dorsay, we'll hear from you.

Julia: Then Al Smith's lawyer, Craig Dorsay, got up to speak.

Archive Clip, Craig Dorsay: Mr. Chief Justice and may it please the court …

Craig Dorsay: When you are arguing, it feels like you're only about 10 or 15 feet from the dias.

Julia: He remembers this day pretty vividly.

Craig Dorsay: You actually physically can't see the entire court cause they're kind of wrapped around you. Since Scalia was new, he was on the end on my left side and Kennedy was on the end on the right side. And they were asking most of the questions and, you know, head is kicking around to try and look directly because you want to engage with them.

Julia: And he said, for starters, this comparison to wine at church — you’re thinking about it all wrong.

Archive Clip, Craig Dorsay: I think if Indian people were in charge of the United States right now, and you look at the devastating impact that alcohol has had on Indian people and Indian tribes through the history of the United States. You might find that alcohol was the schedule one substance and peyote was not listed at all. And we're getting here to the heart of an ethnocentric view, I think, of what constitutes religion in the United States.

Julia: In other words, Christianity is getting a pass. While Native Americans are being persecuted. Plus, he says, a small amount of peyote isn’t proven to be harmful. It’s actually been helpful for recovering alcoholics in the Native American Church. So Oregon has not met that Sherbert Test we talked about — they’ve not proven their supposedly compelling state interest of protecting people’s safety.

Archive Clip, Craig Dorsay: The state has failed to meet its burden under the First Amendment to justify what we believe would be the total destruction of this religion.

Julia: But the justices push him on the other points. Here’s Sandra Day O'Connor.

Archive Clip, Justice O’Connor: How about marijuana use by, uh, a church that, um, uses that as part of its religious um, well sacrament?

Archive Clip, Craig Dorsay: See, I think we can get into a lot of examples, and I don't want to go down that road too far because we don't have the facts here.

Archive Clip, Justice O’Connor: I bet you don’t want to go down that road.

[laughter in the courtroom]

Archive Clip, Craig Dorsay: But the fact is….

Craig Dorsay: She said something like, I bet you don't want to go down that road. And there was laughter, you know, in the courtroom. And that's where we knew we had kind of lost her.

Archive Clip, Justice Scalia: Why can't the state consider…

Julia: And then Scalia pushes back saying shouldn’t governments be able to make general rules like this, that everyone has to follow regardless of their beliefs, with no exceptions?

Archive Clip, Justice Scalia: So long as it does, as long as it generally and doesn't pick on a particular religion…

Archive Clip, Craig Dorsay: Now, the problem is, is this law and the neutral, quote unquote prescription does affect a particular religion only.

Craig Dorsay: And Scalia at one point said, well, you would agree…

Archive Clip, Justice Scalia: Well, I, I suppose you could say a law against human sacrifice would, uh, you know, would affect only the Aztecs.

Craig Dorsay: You know, I was kind of at a loss for words about how to respond.

Archive Clip, Justice Scalia: I don't know that that, that, that you have to make exceptions if it’s a generally applicable law.

Archive Clip, Al Smith: To me it was just like showtime for them. Who in the hell is Al Smith and who in the hell is he, you know? They could care less of who I am. It’s like, how in the hell did they get so high and mighty? And we, the common people, you know, are just, they don't know you or you or me or anybody else.

Archive Clip: The case is submitted.

Julia: And that was that. The last chance to plead his case, in front of the highest court in the land. Where it went from there all seemed like it would be pretty simple, either Al Smith would get his unemployment benefits or he wouldn’t. For now everyone would just have to wait.

Julia: I'm Julia Longoria. This is More Perfect. And we’ve been waiting on a decision. In the most simple form the question of the case is: are Al Smith and Galen Black going to get their unemployment benefits? Or did Oregon have a compelling enough reason to deny them?

Archive Clip, Justice Scalia: The issue currently before us is whether Oregon’s criminal law against the use of certain mind altering drugs ...

Julia: Justice Antonin Scalia, who authored the opinion, announced the result in Court. The headline?

Archive Clip, Justice Scalia: We reverse that judgment.

Julia: Al Smith lost. The First Amendment does not give him the right to break drug laws.

Archive Clip, Justice Scalia: Permitting him by virtue of his beliefs to become a law unto himself contradicts both Constitutional tradition and common sense.

Julia: Letting Al break those drug laws just because of his beliefs? That would make him a law unto himself.

Archive Clip, Garrett Epps: I'm just curious what your reaction is to seeing what the judge, what the Justice wrote?

Archive Clip, Al Smith: Well, I don't know what they wrote, but, you know, my reaction to that is, what else do you expect? I'm, I'm, I'm an Indian. You know, I've received this kind of treatment all my life.

Archive Clip, Garrett Epps: Right.

Archive Clip, Al Smith: My people have, so what, what else is new? You know? So you lost a case at the Supreme Court?

Archive Clip, Garrett Epps: Mm-hmm.

Archive Clip, Al Smith: Well, sure. Of course I did.

Julia: Al didn’t pursue the case because he thought he would win. He pursued it because he wanted his kids to know he was willing to fight. Steven Moore from NARF had warned him this would happen.

Steven Moore: When Scalia and the majority rendered their decision that was just another insult that was leveled on Indian Country. Like you know, you’re now telling us that we do not, that our religion — one of the oldest, most venerable religions in the western hemisphere has no protection under the U.S. Constitution.

Julia: This was a 6-3 Decision. Steven tried to make sense of what had happened — he even went to the Library of Congress and read Justice Harry Blackmun’s dissent, including drafts of it.

Steven Moore: In the first draft of his dissent that was written by his law clerks, it was typed “I respectfully dissent.” And there was a big X through the word “respectfully.” So Harry Blackmun struck the word respectfully.

Julia: A sort of middle finger.

Steven Moore: That’s as close to a middle finger as I’ve ever seen on the Court.

Julia: And it wasn’t just Al, Steve and Justice Blackmun who were upset by this opinion.

Julia: Of course there was like your dad's case and then the court kind of came out with this decision that became like kind of a landmark decision,

Ka’ila Farrell Smith: Right? Yeah. I don't think I really grasped that when I was younger. Scalia, right? That's the justice that I think ended up being like a real — what do they say in reservation dogs? A shit ass.

Archive Clip, Justice Scalia: The First Amendment prevents the government from quote, prohibiting the free exercise of religion, close quote.

Julia: Scalia went well beyond deciding Al’s case. He made a big sweeping statement about what free exercise of religion means in America. The Sherbert Test? That whole you have to have a compelling interest to deny someone’s religious rights.

Archive Clip, Justice Scalia: We reject that interpretation.

Julia: Yeah, that’s dead.

Garrett Epps: Everybody is sitting around saying, this isn't even, this is not even our case. What, this must be a mistake. They're faxing the wrong thing, or there’re pages missing this, you know, nobody has asked the Court, none of these issues were posed in the briefs. None of these issues were posed in the argument. What, what's going on?

Julia: Professor Garrett Epps again.

Garrett Epps: I don't have insight into Scalia's mind. God knows. But he was on a mission that had nothing to do with peyote religion. He was trying to do something about the general religious picture in the United States.

Julia: Justice Scalia felt uncomfortable with the idea that judges would be the ones deciding what’s a compelling enough reason to throw which religion under the bus.

And in this, he had a point. Take one uncomfortable case from the ’70s. The Supreme Court sided with Amish families, saying they could break truancy laws that require kids to go to school. One judge wrote:

Garrett Epps: Yes, these are the sturdy yeomen that Thomas Jefferson believed would be the salvation of the American Republic. Of course, you can't make them send their kids to school, but we want to make clear that this doesn't extend to — he doesn't use these words — but it doesn't extend to like hippie sects, you know, or, or strange groups of people from other countries. It, it's these good American people, and it's like, you read it and you want to hide your face.

Julia: Scalia’s stated philosophy was let’s just not have judges make these kinds of calls.

Archive Clip, Justice Scalia: In this job, it's garbage in, garbage out. If it's a foolish law, you are bound by oath to produce a foolish result because it's not your job to decide what is foolish and what isn't. It's the job of the people across the street.

Julia: In practice, it was a philosophy he applied pretty inconsistently. But in Smith, with the rights of Native American religious practice on the line, Scalia decided to stay in his lane and left lawmakers to make laws. There was a new test in town much easier for lawmakers to pass. As long as a law was general, and didn’t target a particular religion, it was fine. You don’t need to have a compelling reason for it to violate someone’s religious beliefs.

Scalia wrote if we had done what Al wanted us to do, the government would have to give people all kinds of exemptions from laws. It would let people get out of everything from compulsory military service, to the payment of taxes, to health and safety regulations, to compulsory vaccination laws. Scalia’s like, you simply cannot have 300 million people all deciding what laws they’re not going to follow based on their beliefs, that would be chaos. Which does beg the question — then why do we have a First Amendment right to freedom of religion at all? What does it get us?

Dan Mach: The ACLU thought the decision was wrongly decided, we still do.

Julia: This is Dan Mach, director of the ACLU Program on Freedom of Religion and Belief.

Dan Mach: Why was it wrong? It leaves minority faiths out in the cold. Justice Scalia said, sure that will disadvantage minority faiths because the political process is not going to respect them, but he called it an unavoidable consequence of democratic government.

Julia: Immediately after the decision came down, there was a huge bipartisan, interfaith backlash to Scalia’s decision. Democrats. Republicans. The ACLU. Christians. All wanted this Court decision gone. The thinking was if this could happen to the Native American Church, it could happen to any of us. The First Amendment needs to mean something.

So almost as soon as Scalia put it out into the world, people have tried from all angles to un-do this ruling. They tried in the courts. They even tried passing a law in Congress. But ultimately, the Supreme Court has stood by the Smith decision. It’s stayed on the books for the last 30 years.

And what that meant if you were a religious person looking for an exemption from a law — at least for the first few decades after the Smith decision — is that you had an uphill battle.

Dan Mach: The exemptions were only gonna be if the majorities deemed it okay. And I thought that was a problem. The key for me though, in these cases is what's the harm of granting the exemption?

Julia: Like is anyone harmed when you let Al Smith eat peyote? Or is anyone harmed when you let Adele Sherbert take Saturday off from work?

Dan Mach: Sometimes the harm is nothing. Sometimes, however, there can be a great harm. And, and that's where I think we're moving these days.

Julia: Lately, the Supreme Court has been handing out exemptions pretty readily to certain religious groups.

[Archive Clip, News footage]: And in fact this term, we’ve seen the court repeatedly side with religious institutions when it comes to COVID restrictions where the court has said no the state cannot burden religious institutions.

[Archive Clip, News footage]: So it's a victory for Catholic Social Services. It's a defeat for the city. But the Supreme Court seems to have gone out of its way here to make this a very narrow ruling. That is not a green light for other organizations to feel that they can now cite religious freedom in violating anti-discrimination laws.

Julia: Today, you might say some of Scalia’s worst nightmares — about everyone becoming a law to themselves, the whole reason behind his decision — are coming true anyway, even with his Smith decision on the books.

But the politics around religious freedom have shifted. For one thing, same sex marriage has been protected in the Courts and by Congress. And the people in front of the Supreme Court now aren’t from minority religions like the Native American Church or Seventh Day Adventists. They’re people from majority religions.

A Christian cake baker who objected to serving same sex couples, A Christian wedding website designer who objected to serving same sex couples. A Catholic foster care agency who objected to serving same sex couples. They all now see a Court friendly to their interests and have all asked if they can break a general law, an anti-discrimination law that doesn't target their religion.

So far, the Court has sided with religious people, and has allowed them to sidestep these anti discrimination laws. In effect, allowing discrimination against queer people.

But these lawsuits have also asked the Court to overturn the Smith decision, something the Court to this point has refused to do.

Justice Samuel Alito wrote it’s time to overturn Smith.

Others fear that going back to how it was before the Smith decision isn’t right either.

Dan Mach: Religious exercise is incredibly important. It's a crucial, fundamental right.

Julia: Dan Mach from the ACLU again.

Dan Mach: But it's not just a free pass to harm other people. It was meant to be a shield to protect religious adherence, not a sword to be used to discriminate and harm others.

Garrett Epps: You know, I wanted, I have wanted, I spent years wanting Smith to be overturned. Be careful what you wish for.

Julia: Professor Garrett Epps again. He says courts like the Supreme Court aren’t exactly set up to parse nuance. And even though they might have gotten a reputation over the years for being the protectors of minorities, Garrett says they don’t have a great track record of that either.

Garrett Epps: Congress has done much better at protecting minority rights than the Court. And you know, we’re seeing episodes now where the court’s gonna step in and say to the state of Colorado, you can’t protect gay people against discrimination. You know, you can’t protect same sex couples. The court's record is not particularly good. And if you ask yourself why that is, it's clear. So like, these are nine well fed, well educated lawyers. And if I wanted some deep social pronouncement about how to make America better, I wouldn't ask nine well fed lawyers. Protectors look ahead. They see the danger that's coming. They try to diffuse it. That's not what judges do. I love them, bless their hearts, but it's not what they do.

Archive Clip: It’s now a great honor and pleasure for me to introduce Mr. Al Smith.

Julia: Back when the decision first came down in 1990, Al Smith was asked to give a talk at Berkeley.

Archive Clip, Al Smith: Good afternoon. Well, I'm really surprised and pleased to be here. Glad you showed up. Before I get into expressing, uh, what I need to say at this time, I, I want to speak to my brothers and my sisters that are in this audience and perhaps others that may be listening to a tape.That I, I wanna apologize to you my brothers and my sisters of, uh, who are Natives of this land. If any way, uh, this case has harmed you, I apologize for that.

Julia: In the Smith opinion, Justice Scalia basically told Native Americans, take it up with Congress.

And a few years later, they did. Native Americans convinced Congress to pass an amendment to the American Indian Religious Freedom Act, which read, quote “the use, possession, or transportation of peyote by an Indian for bona fide traditional ceremonial purposes in connection with the practice of a traditional Indian religion is lawful, and shall not be prohibited by the United States.”

Today, the fear from Native Americans of taking their case to a Court that is hostile to their interests is very much alive. This term, the Supreme Court could strike down a decades old law — the Indian Child Welfare Act. Tribal experts fear that would threaten all of tribal sovereignty. We’re still waiting on a decision — stay tuned for that.

But for Al’s purposes. All he wanted was for his kids to know was that their dad was somebody who would stand up for what was right. Even if the odds were stacked against him.

Ka’ila Farrell Smith:When I travel and people in Indian Country, oh my god, they're like, yeah, because of your dad that can do all of this. Ceremonies, like practicing their art. I understand how important it's from, like, what other people tell me.

Julia: Ever since Kai’la moved back to where Al was born, on Klamath lands, people tell her they got protection for the sacred medicine because of Al’s fight.

Ka’ila Farrell Smith: I've had intense dreams where he like shows up. Like, I'm like, oh my god, my dad's here. You know? Like that has definitely happened since I've been home. And I don't know, you know, and it's good, you know, sometimes I wake I woke up in a dream and it was like, he was real, like he was right there. I remember just like hugging him and it was like, and I woke up like crying. I like, oh my god. It was like I got to see him again. Like, right now I'm getting emotional, like thinking about it.

So I told, you know, I kind of made a pact with my dad, I was like, okay, well when I'm making art or doing art, like that's when we can hang out . And I was like, or in the water. So that's why I spent a lot of time kayaking and that's like my way of like, being with him.

I've taken my mom down, you know, the Williamson River kayaking and there'd just be huge bald eagles that just just like fly right over you and land in the trees. And, you know, she's like, that's Al! I'm like, sure.

The water, this land, this place, Al was taken at age 7 years old. There is hard stuff. I'm just like, everything doesn't have to be such a hard memory, you know, like, let's make new memories.

This episode was produced by Julia Longoria with help from me, Alyssa Edes. It was edited by Whitney Jones and fact-checked by Tasha A.F. Lemley.

Special thanks this week to Samuel Moyn, Andy Lanset, Tasha Sandoval, Micah Schwartzman, Shlomo Pill, Raphael Friedman, Connie Walker, Mary Hudetz, Samantha Max and the University of Oregon Libraries.

The More Perfect team also includes Emily Siner, Emily Botein, Gabrielle Berbey, Salman Ahad Khan and Jenny Lawton.

The show is sound designed by David Herman and mixed by Joe Plourde.

Our theme is by Alex Overington, and the episode art is by Candice Evers.

If you want more stories about the Supreme Court, we’ve got lots. Go to your podcast app, subscribe to More Perfect, and scroll back for more than two dozen episodes.

Supreme Court audio courtesy of Oyez — a free law project by Justia and the Legal Information Institute of Cornell Law School.

Support for More Perfect is provided in part by The Smart Family Fund and by listeners like you.

Thanks for listening.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.