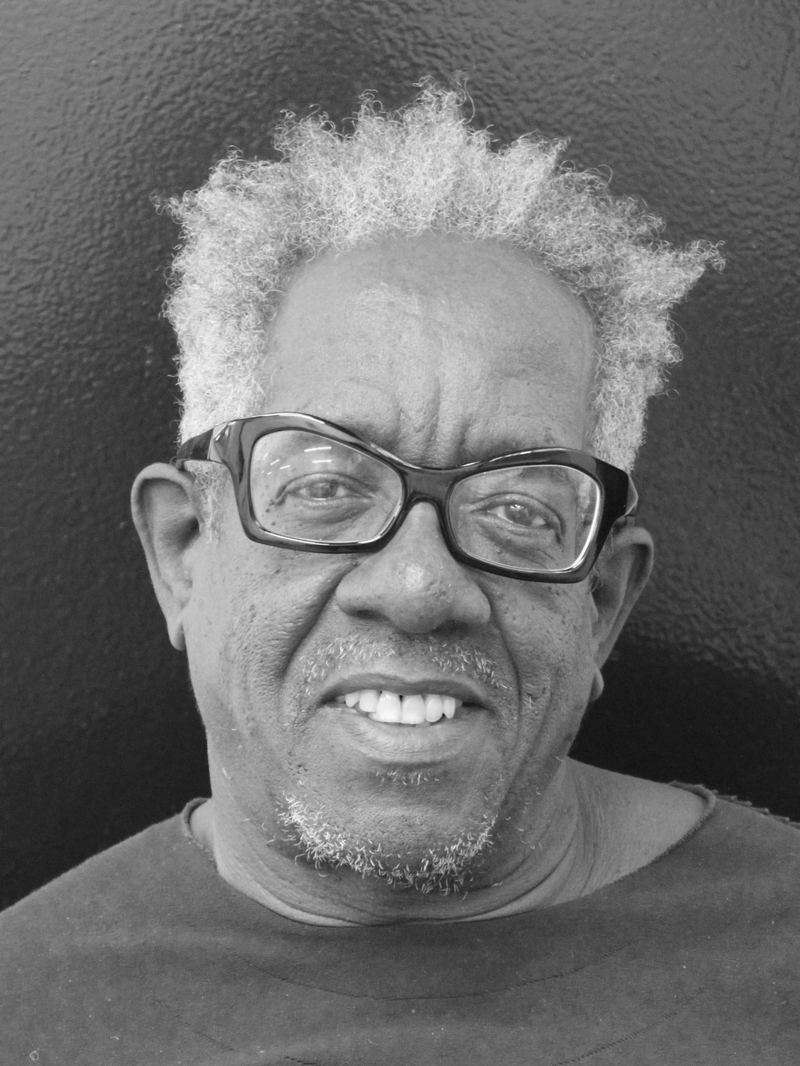

Artist Stanley Whitney on Black Identity and Abstraction

( Miranda Leighfield )

Stanley Whitney Transcript

Stanley: A lot of young black artists like my work a lot. Which I was shocked. You know, we love your work. It sets us free. We can do whatever we want because of you. I was really surprised. You don't even know who love your work.

Helga: His path is along the grid. His use of color and its placement helps to focus our attention on the work itself.

I'm Helga Davis and the biggest challenge visual artists, Stanley Whitney faces each day, is that of the blank canvas.

This steward of color and pigment has been on a journey to free himself and us from the confines of narrative painting. Where I'm allowed to imagine what I could be. Could it be?

He joins us here to talk about the mini turns, roadblocks and evolutions he has made in his life as an artist and as a person.

Stanley: How are you?

Helga: I'm great.

Stanley: Good.

Helga: Here we are with Stanley Whitney.

Hi Stanley.

Stanley: Hi.

Helga: Where are you coming from?

Stanley: A home. Cooper's square.

Helga: Okay.

Stanley: Yeah.

Helga: Have you been in the city for a little bit?

Stanley: No, I've been here. I mean, people say I travel a lot. I don't think so.

Helga: And you also are in Rome a little bit.

Stanley: I have a house outside of Parma, so that's a five hours North of Rome.

Helga: know, my European artist friends work here, and I work there. We're always in search of some kind of other. So here, the dancers, the painters, the singers, they come here, and they work. And then I get to be the American there.

Stanley: Well, you know, for me it's really, it's good to get out of the country totally. So, we've been doing it now almost 20 years.

Helga: Oh, that's a long time.

Stanley: Yeah.

Helga: I didn't realize it was so long. It's important to you to get out of the country because?

Stanley: Just to be some place that people think differently. And you know, it's funny cause, you know, where I am in Italy, in the country, in little small town Solignano, they think artists are quite special, you know. So, they really embrace you. You're kind of a special being, you know?

Helga: But you're also an African American man living in-

Stanley: Well, that's true, you know? That's true. And that's interesting because they see you more as a human being. I mean, if they have some issues, it's maybe because your people have issues about Africans or people come from Africa.

I mean Italians have a hard time accepting people who aren't born in Italy and been there for centuries, you know? But in terms of being human being, they treat you very well as a human being.

Helga: You don't feel that it's as bad as it is here.

Stanley: No, no, I don't. I mean, I think if you're immigrant or you're- I mean, there's a lot like where I am in the country. There are a lot of Nigerian guys who come there. And they can get in, but they have to beg, you know what I mean? So-

I mean, it's all family oriented. So, people don't rely on government. You rely on family.

Helga: I think about you when you say this thing about people understanding the artist. I think about you in a group of black men who for me have a kind of, or exemplify a kind of freedom of expression, of self-determination. So, let me name the people and then maybe that helps.

Stanley: Okay.

Helga: So I think about Butch, Butch Morris, I think about Henry Threadgill, about David Murray, about David Hammons. That you are all African American men of a generation. Maybe you're born a little bit after World War II. But you come up in cities through Civil Rights and you make a very different kind of determination about who you are as men, who you are as black men, how you're going to live.

Stanley: Yeah.

Helga: What you're going to do, who you want to be.

Stanley: In fact, David Hammons and I, one time we were in Rome. We were singing in a club and someone said, "You guys want to play." We should have done it.

Because you know, you kind of looked the, you know, if you're a black male and you're kind of not dressing sort of, you know, when you say "normal", I guess you're always trying to set yourself apart. And New York really sort of like encouraged you to do that, or it did. I mean, I think New York now is sort of more suburbanized.

When I came in New York too, I was downtown person.

Helga: Downtown where?

Stanley: Well, if you're gonna com to New York, I mean all the artists lived on Bowery. And it was empty. There were lofts that no one really wanted. So, I mean, it was full of, you know, derelicts and drunkards and things like that. People were always drunk on the street. It was a big mess.

Helga: You say it and I feel like you're waiting for me to be surprised. But we pass that every day right now, also. With people just kind of laid out in the streets, so.

Do you feel like seeing that every day, people on the streets, people in your doorway influenced your work also?

Stanley: No, I was just trying to figure out who I was. I was trying to. Figure out sort of what my obligations were to everything. To community, to race, to painting, to contemporary painting, to being in New York, you know? It was like really for me I was trying to figure out everything.

Helga: What did you feel your obligation to the race was?

Stanley: I wanted to paint, you know what I mean? And I was a painter. Everyone was trying to tell people who they were, what they were. And I was fighting to be very independent because my work now, I think. There's a lot of freedom in my work.

I mean, even when I was in school and Kansas City during the riots in the 60s and I couldn't explain myself. I couldn't defend myself. Because if the black Panthers came by and said, "Stanley, you know, what are you doing?" You know, I wanted to be in the basement painting.

And I'm looking at Goya and I'm looking at Edvard Munch and I'm looking at a lot of paintings. So painting seemed to be the thing I had to do. I kind of painted a war, I felt like.

New York was, total freedom. I immersed myself in the art community, you know? It was hard to figure out sort of like- people were kind of like not involved with each other in terms of race so much. Although I kind of really was about trying to figure out myself. I'm kind of a loner. Even now.

Helga: And how does that affect your career? Let's say.

Stanley: It affects your career because, you know, I didn't really, you know, trust people. So, you know, those people I knew who I was involved with in terms of painting and art, looking at art. Then the people I was involved with in terms of really black culture, you know what I mean? They didn't always overlap. You know what I mean?

It was really complicated because you had all the different things going on. And you're sort of looking for where am I? Where do I fit into all this?

Helga: And where did you fit into all of that?

Stanley: I didn't. I didn't feel I did. I sort of made myself up I thought. I kind of feel. But I think as an artist you do make yourself up. So, I wasn't looking to fit in anywhere. I was looking to think about what I, what my needs were. And what my obligations were. And I realized my obligation really was to make paintings.

Helga: Was there an obligation to your family, to the community that you came out of that you felt?

Stanley: I didn't feel so, noa because I came from a very small block community that- they were sort of backwards people you say. But they lived in- outside of Philadelphia and Bryn Mawr. And the they kind of worked at estates and they kind of built Bryn Mawr College, Haverford College, Villanova. Then they got to stay there because it was a safe haven.

No, they had no idea. I was a radical. They had no idea what I was doing.

Helga: I'm just trying to think about- or put myself in the place of your parents.

Stanley: My parents were very supportive in the sense they didn't know who I was, but they never got in my way. They didn't know what art was. We didn't ever go to an art museum. We never looked at art. We didn't do any of that.

We lived above my father's store. We were pretty poor and very rich neighborhood outside of the black community. And then my father was a small businessman on Main Street, and we lived above the store. Which was a big thing.

But they, they never got my way. I mean, they didn't know what I was doing, you know? I didn't know what I was doing. I just knew I wanted art school. I always drew my whole life, you know what I mean? I always drew, always drawing. But I had no idea.

I could think really well when I painted. I felt that was my home base. So, then I was trying to figure out sort of what that was. I didn't know any black artists, you know what I mean? I didn't know anything in terms of art history. So, I spent all those years really educating myself, you know and New York seemed to be the best place to come to educate myself.

Because I didn't even know the kind of painter I was.

How come?

Because I was seeing work I liked, but I didn't know really what that meant to me. You know, like you would see a Barnett Newman painting, which would just be like, you know, maybe blue with a red line down the middle. And I would think, you know, coming out of European painting about the European School, what that was. I had to really work hard to figure out sort of really how I was involved.

I was a colorist. I always was a colorist. If I didn't know what that meant in terms of subject manner. I didn't know the color could be subject matter at that point. So, the thing that really kept me focused were the musicians. And the music seemed to be, that radical black music seemed to be the thing that I identified the most with. I mean, I kinda think in my paintings as that.

Helga: Did you go to Vietnam?

Stanley: No, I didn't go to Vietnam. I went to art school and I got a student deferment. I think because everyone else had got drafted. Actually, it's funny, in my community and our high school, maybe there were like maybe 10 black people. That's all.

But in my high school and my class, there were three, three, three of us who were artists. Like this guy, Jimmy Phillips, who teaches at Howard. Harry Pala, who was just so talented, but just recently died. He was- I was in school with him. He was fantastic artist, but he never got past the neighborhood. And myself. And we were artists, you know?

Jimmy came to New York cause he was the last carrying name of his family, so he didn't get drafted. This guy Harry Pala who called, we called "Flubby", he came to New York too. But he got drafted immediately. You know, he didn't go to Vietnam. It was early on '64 so he went to Germany.

I went off to art school and I think because there were enough people who were getting drafted, they left me alone. So then when I came out in '68 art school, I came to New York.

And by that time the war was winding down and I got out because I had asthma as a child and I got a doctor who was Anti-War to write me a letter, saying I still had asthma. So, I got out. But you know, it hung over your head the whole time.

I think my friend Flubby, when he tried to get out '64, he told them he was a black Muslim. He told me he was gay. And the FBI came to the neighborhood, you know, and went down everyone's house and asked about him.

remember my father said the FBI came. You know in the black community, when the FBI showed up, they're like, whoa, whoa!

And they assured him, "Oh no, he's a very sweet guy." So, he got drafted. You know?

Helga: Oh.

Stanley: Because they said, "No. He's not a black Muslim. He's a good Christian. No, he's not gay." You know? So, he got drafted.

Helga: Do you remember when your school was integrated?

Stanley: I went to an integrated school my whole life.

Helga: Oh, you did?

Stanley: Yeah. But they were integrated in the sense that from kindergarten to high school, there were never more than.10 of us, at the most in the school. At the most. So, it was a very small black community. Very small.

Helga: And what was that like?

Stanley: We went to school and that was it. You never heard about yourself.

Helga: And you never saw yourself.

Stanley: Well, you only saw yourself. There weren't even, even the janitors weren't even black in those days. The bus drivers couldn't get a job. The kitchen people weren't even black in those days. You couldn't get a job.

But the thing about the black community, you know, is there's a thing about song and laughter. And, and playfulness that you can deal with these things and, and still have joy in your life, you know.

For me, you know, I think the way we all survived is through the music. You know? I think we wouldn't have survived without the music. The secret of black song and laughter. I think it's the music, you know? So, to me, the music is very important.

Helga: I love that you are talking about your work in terms of color being it's subject, at a time when like we really need to see ourselves in places.

Stanley: It's true. And I think if I can say the danger is, is who says who we are, if we take charge of saying who we are. And not what people were supposed to be.

Like when I was in high school, I was small guy and they wanted me to be on the crew and be the guy who says, you know, "Stroke, stroke, stroke" you know. And I said, "Black people don't do that."

I mean, now why do I have this idea what black people do or don't do. You know what I mean? Who's told me that, or where'd I sense that, or where'd I get that from?

So I think, you know, I mean, even my paintings when I used to first showed them in a place in Austria. Someone said, "You did that?" Cause it's like, who's owns what? Who owns what? So I think, you know. Or I've had even black collectors who said, "Oh, Stanley Whitney's black. I didn't know he was black."

Helga: What does that do to you Stanley?

Stanley: I think it's a good thing. I think it would be- yeah, because I think it opens up who we are. And what we are as human beings. I mean, we're really there in the world right now. Who owns what? This is my land. This is my border. This is, you know, you can't come here. You're illegal.

So, I think art really put everything in the question. So, I wanted to make art really that put everything in the question. You know what I mean? Everything who I am in my work. And I think, you know, I grew up with freedom, freedom, freedom, freedom. So, I have paint a lot of freedom. My work is totally open and free.

Helga: You have a son?

Stanley: Yes. I have a son. He's 25 and he's a writer. And, he seems to be very happy and healthy. And that's really important.

Helga: Where's freedom in his life?

Stanley: Well, I think, you know, it's very, it's very hard with that because things change every generation. So, what my experiences are and what his experiences are totally different.

I mean, one time he did come home late one time out of high school at some party and he ran and I said, "Look, never run. I don't care how late you are, I never run." He ran from the subway home. I said, "No, you can't run. Never run."

But my parents raised me so I didn't come a bitter, you know what I mean? They kept us away from things, you know what I mean? I never saw anybody talk bad to my mother or my father, you know what I mean?

So I raised my son, he has a sense of what it is, but he's never had a bad experience, you know what I mean? He's never- I don't think he's ever had an experience like I have, you know what I mean? He's never been arrested, or he's never been, you know, confronted in any kind of way. I was in Kansas City during Wallace’s, you know, when he was running for president and I was in Columbus, Ohio, so I was arrested a couple of times.

Helga: For what?

Stanley: Well, one time in Columbus, I was picked up supposedly for robbing somebody, but then and I wasn't.

Helga: And what else?

Stanley: And then in Kansas City, I had some big party and we all got thrown into the jail.

Helga: For what?

Stanley: Well, it was a big party, cause it was mixed, really. Lots of white- it was mixed. And we had, we had my roommate he was white, I was black. We were living outside of the artist community.

And we had this big party and I invited a lot of the black community people there. So, we got- everyone went to jail that night. But-

Helga: But Stanley, this is extraordinary.

Stanley: Not taking the story. It's a funny story too,

Helga: Well come on with it.

Stanley: It's a funny story because me and this a guy who was my roommate, we had this Arthur Murray dance studio in Kansas City. But next door was a burlesque house. And so, we were really poor so we said, let's throw a party where we invite, you know, people will bring food, you know, and stuff like that. So, we invite the whole art school. Students came, faculty came, and I also invited people from the black community.

Helga: So, where they, were these, were there other black people in your art school or, no?

Stanley: No, not many. But I was used to situation where I'd be one or two or three. That was my whole life experience, right. You know, the negro by the door, you know what I mean? That they use you for, "Oh, that room's integrated."

Helga: For the record, I've never heard that expression before.

Stanley: What's that?

Helga: The negro by the door.

Stanley: Well, the expression in those days was that if you're going to integrate, right. So, the idea is you take one black person, put them in the room and it's integrated.

In art school it's not so much about black or white because in arts school- school is a big equalizer. At least it was in the 60s for me.

School is a big equalizer. You're a good painter, you're a bad painter, you know what I mean?

Helga: Well, how can it be an equalizer if you're the only black person?

Stanley: Because people aren't questioning you so much and people aren't really giving you a hard time. You're just a human being and you see yourself more as a painter. So you're living sort of like this kind of like, in some sort of fantasy world.

You know it's not real. It's school. School is not the real world.

Helga: All right? So, you have this party.

Stanley: I have this party. The cops who are in the real world bust the party. Paddy wagons come. Everyone goes to jail.

Helga: Why do they bust? Why?

Stanley: Because they saw blacks and whites mingling together.

One of the guys who taught at Kansas City, Kelly, his brother was a police chief who became head of the FBI. And so, because of that, and because the newspaper didn't get a hold of it and the school was totally freaked out, they didn't press charges and they let me go. And they told me you had to leave, I had to leave the next day.

Helga: Is there something about the word, the label artist that is protected you?

Stanley: Yeah. You have to really make yourself the artist or really claim yourself as the artist, you know what I mean? But once you become the artist, I think that's true.

It's funny cause my neighbors in Italy who were just farmers or were farmers or just workers, now they will tell you you're a very special person. You're an artist.

Helga: Do you think you could not have made yourself an artist if you only lived here in the United States?

Stanley: I think only United States can I become an artist? I think if I were in Italy, I couldn't have been, I wouldn't have ever been an artist. It'd be pretty hard to do it in Italy. And the thing about the States-as bad as it is, as racist as it is, how awful it is, how sexist it is. As an individual you can do a lot of things.

There's so much freedom, which I think people have a hard time with. If you're an immigrant, I think you see it. You can how you would want to come here, you know? Who will do anything to get here. Because really you can really make yourself up, you know?

And yeah. So, I made myself up. I don't think that I could've made myself up any place else. Fine.

Helga: So, I got, this is- Donald Judd's writings. First of all, I think it's a beautiful object, but here's a thing in here that I would love for you to respond to.

Stanley: All right.

Helga: Artists are generally treated and sometimes act like unowned serfs waiting for an owner. The patronizing attitude includes interference in the production of the art, pressure to make saleable kinds of art, and suggestions as to how to live. It is a disgrace to work for nothing. To have your desire to make art used against you. It's a disgrace to be cheated, to be played with, and to be patronized.

Stanley: Yeah, that's true. I mean, that's Donald Judd. Yeah, that's- I agree with some of those things. Yeah. I think, I mean the New York art world, even when I got here in '68 was a smaller world, you know what I mean?

Helga: Yea, but at a certain point, you started making money and something in your life changed.

Stanley: I'm trying to hold the line. I see myself as really- I've been painting so long, by the time they got to me money-wise, my habits are so strong that I'm in the studio and the money's not there. The studio just stays the studio, you know?

People now want the work. People are interested in the work. I'm not sort of a front room kind of artist. I mean-

Helga: I don't think any of this is true. Something has to change Stanley, because literally-

Stanley: How does it change?

Helga: If you, if you want to not be in the studio for three months cranking out things that you hope will sell.

Stanley: I couldn't not be in this studio.

Helga: But let me finish this. And you want to be in your little village in Italy helping your neighbor mow his or her lawn. And you can play at farmer. You can be a tourist at farmer for some months. That's a huge luxury. And that has to have changed something.

Stanley: The studio hasn't changed. Outside of the studio? Yeah. I mean, if I want to go out and buy whatever I want to buy, I can do whatever I want. But the studio hasn't changed.

Helga: But how is that possible?

Stanley: Because the studio has always been the same studio. Whether it's money or no money. I'm facing that blank canvas no matter what.

The thing about it is, if you become a successful artist, you know, and you make money, you can support yourself and there's nothing in your way I can work to my potential. But the studio hasn't changed.

Helga: Well how is that possible?

Stanley: Cause I'm trying to deal with great art. I kind of want the art to be placed next to great art. I'm not thinking about, well how much is it going to sell? Whether they're going to sell. That's not the issue.

The issue is what it looks like next to de Kooning? What looks like next to any great artist you want to pick. That's the issue. That's the only issue.

The fact that someone buys and takes her to the house or whatever. That's great and everything, and you want to have something that's, you know, I kind of feel I can sort of radicalize people if they take my painting and put it in their house. Because the art world's a secret world.

Learning what the gallery scene was, you know what I mean? Learning how galleries work, learning how dealers worked, learning how- what money was. I'm not going to try to fit in. I'm not going to be who you tell me to be.

I'm going to take everything and do everything and do everything I want to do on my terms.

Helga: And that's what you're doing? I mean, that's how I feel.

Stanley: Yes. Yes.

Helga: But that's also what you do.

Stanley: Yeah. Yeah. And you risk everything. It's, it's big risk. It's big- it doesn't have to happen. But you know, I'd go to my studio and I would say it's worth it. You know, I like what I'm doing.

Cause I would go to my studio and think, "Look Stanley, you don't have to do this. You can do something else. You can, you can make your life." And I would say, "No. I like what I'm doing. I'm going to keep doing it."

It's like believing- it's like really believing in yourself, you know? Totally believing in yourself.

Helga: Do you have some practices, some things that you do every day that are kind of pedestrian that before you, before you get to the canvas?

Stanley: Not so much anymore. I used to do that a lot more. You know, I used to, early on I would get- I lived when I lived in Tribeca and I had a studio in Coopers Square I would get up, I would look at like, maybe a Cézanne book or different art books. I'd play some music and I'd walk through Soho and I go look at all the galleries. And I'd get to my studio and look at my art and said, "Stanley, you know, you know what they like, you can do that, and you keep talking this." And I'd go, "I'll keep doing this."

Now I get up and I just go to the studio. You know, I just get up and I either- I have a studio in Bushwick. I either drive to the studio or take the subway to the studio. And I can go to the studio- I go to the studio every day.

Helga: [00:25:49] You go every day?

Stanley: Every day I go to the studio. I cannot even be in the mood to paint, but once I get in the studio, I paint.

If I don't paint, I can get a little crazy. You know what I mean? You sort of developed an addiction. And I think better when I paint. I have a sense of space. I just, I'm just a better person if I paint. I move better. I have a sense of myself better if I paint.

Helga: Does it matter to you who owns your work?

Stanley: No. Once you put it out in the world, you put it out in the world and it's kind of gone. It's not, it's not in your hands anymore. I have a dealer, I show at Lisson Gallery in New York and London. And they said, "You know Stanley, the thing about your paintings are the people who buy your paintings seem to be really people who are really, people who really care about life. Certain kind of people buy your painting. Which I'm happy to see.

I mean, I had a painting once, a woman who was dying of cancer, and she had a small painting of mine, and she really liked that a lot. To have it, you know, cause she knew she was dying. But no, I don't really, I can't control that so much.

I don't have that kind of power yet to say who can have it, who can't.

Helga: Does it matter to you whether or not black people buy your paintings or can buy your paintings?

Stanley: Honestly, no, it doesn't matter. You know, I think you know a lot of people who have money, and I don't think the black community so much has embraced art or artists.

Helga: Why do you think?

Stanley: People don't see how art will better the community. Now I think they do. But there's still want to see images of themselves, you know what I mean?

Helga: But how do you think we develop a community or an audience of people who see it as a necessity?

Stanley: I think that's happening in terms of what's happened the last oh 10 years in terms of black artists from anywhere. From Africa, anywhere in the world who are showing in the world. Things have changed radically.

So it's happening, but it's slow. A lot of young black artists like my work a lot. Which I was shocked. You know, "We love your work. It sets us free. We can do whatever want because of you." I was really surprised.

Like artists are very delicate. You know, artists can go into the studio and they can kill themselves because they think they're on their own. No one cares. And then they die and people go, "Oh, we loved that artist's work." You don't even know who loves your work. You know what I mean?

But no, my work is to touch people. Whether they're Black or White or Indian or Chinese or Korean. I see myself as someone hard to get to.

You can walk in someone's house and you can look at their art and you know who they are. You go, "Oh, ok. I know who you are." You know? It'll tell you everything. I don't think it's that easy to get to my art cause you- there's no story there. You have to be free about it.

And I kind of want a hard to get to. It's just where I am. It's like what I want to be. The kind of freedom I want. It's kind of like you have to bring something to it. The work doesn't just say, "Oh, here." It's not religion, you know what I mean? It's not a Church, you know. It's not religion. And you sort of like, you have to sort of face yourself.

What is that? What am I? Who am I? What am I doing? What are my beliefs? A question, question, question, question.

Which I think is a good place to have and people have in their house. So, I tried to paint paintings at people in their houses. People, if they look at them and live with them, and every time they see it's going to be different and it raises a question. It's a good place to think. It's like mentally wandering.

Helga: Thank you, Stanley.

Stanley: Yeah, sure.

Helga: I'm Helga Davis and that was my conversation with Stanley Whitney. Helga is produced by Krystal Hawes Dressler, and myself. Our technical director, composer, and sound designer is Curtis Macdonald. Lukas Krohn-Grimberghe is our Executive Producer. Special thanks to WNYC's Program Director, Jacqueline Cincotta and Alex Ambrose.

Be sure to visit us online at wnycstudios.org/helga.

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.”