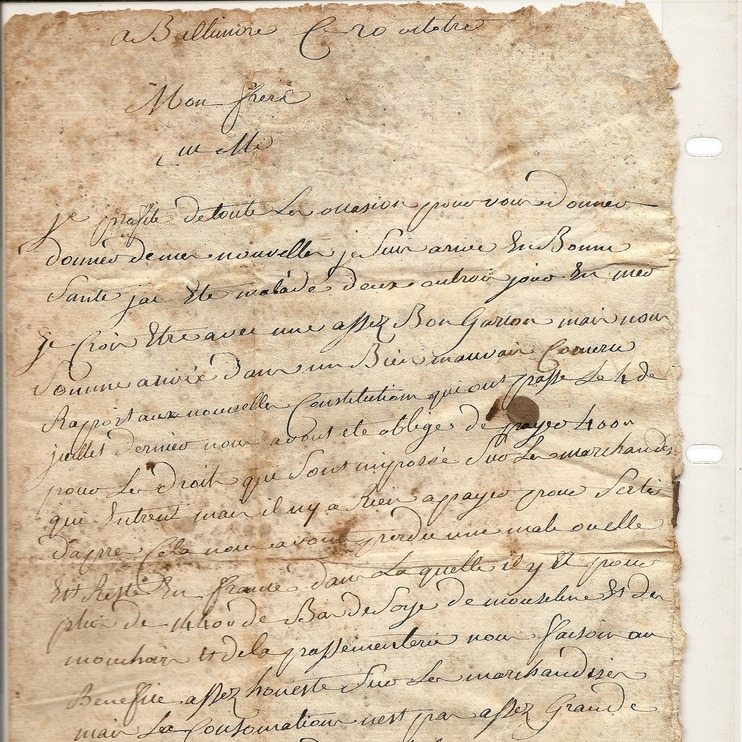

BOB GARFIELD: Okay, so drop everything you’re doing and just wire me $2,000. Don’t worry, I just need to get access to a vast fortune left to me by a distant relative who just happens to be a Nigerian prince. I promise that when I get the money, you will get a big cut. An oft-told tale, that one, the notorious Nigerian e-mail scam. Seems like a product of the Internet but, actually, it is just the latest iteration of a con game dating back centuries. Case in point, the “Spanish prisoner” scheme, prominent in the 19th century, during the Napoleonic Wars. In that scam, the letters, though often penned by conmen in Britain, seemed to have come from Spain. The letter recipient was entreated to send funds to a man imprisoned or otherwise confined who would use the money to get access to his fortune. Once he did that, he vowed to share the wealth with his benefactor.

Robert Whitaker is a PhD candidate in the Department of History at the University of Texas at Austin. He wrote about “Spanish prisoner” letters for the history journal, The Appendix. My esteemed PhD candidate Whitaker, my most enthusiastic salutations of the day.

ROBERT WHITAKER: Thanks unto you, too.

BOB GARFIELD: Your favorite in the genre is one you found written by a person who called himself, Luis Ramos. What was his pitch?

ROBERT WHITAKER: Yes, so Luis is stuck in the military fortress in Barcelona, or so he claims.

READER: I have been condemned by my political enemies to 16 years of penal servitude that I must extinguish in this fortress, where I am suffering so bitterly that I am deprived of all communication outside, even with my daughter.

ROBERT WHITAKER: He’s come to know their address either by looking up obituary notices or by looking in the phone book. And he’s offering up his marks 37,000 pounds in return for some help with some legal fees. He's offering up also his 14-year-old daughter. He wants the mark to care for this child.

BOB GARFIELD: You’re talking about his target, his sucker.

ROBERT WHITAKER: That’s right, yes.

BOB GARFIELD: And, it worked?

ROBERT WHITAKER: Well, it depended. He’s writing in a pre-Internet age, and so, he doesn't really have a good sense as to where his marks are actually located. In some cases, he sends it to the wrong address. There were several cases were Ramos actually sent a letter to somebody who'd been dead for a number of years. In some cases also, Ramos got the name of the potential mark incorrect. For instance, instead of writing to Mr. Harry Robinson, he wrote to Mr. Robertson Harry –

[BOB LAUGHS]

- and said that he knew Mr. Robertson Harry through his wife, Mrs. Mary Harry.

BOB GARFIELD: You mentioned the Internet. When we’re speaking of Nigerian cons, those email blasts go to millions and millions of people, of whom one might likely be enough of a sucker to bite. The handwritten Spanish prisoner letters couldn’t have reached more than a handful of prospective victims. How in the world [LAUGHS] could these things have paid off?

ROBERT WHITAKER: Even though Ramos had to do more work in order to try to get that money, this was his profession, right? He was a career criminal. You know what's amazing about Ramos's letters is that they’re so well-crafted. In addition to the actual letter, he also supplies supporting documents, evidence that he's actually in prison and that his story is true. The initial notice of arrest for Ramos, newspaper articles saying that Ramos has been arrested and then, also eventually, because the nature of the Ramos drama, it also includes Ramos's death certificates.

BOB GARFIELD: Now, the “Spanish prisoner” goes back at least a couple of hundred years. Going back only a century, you say that the early part of the 20th century saw a huge surge in this scam.

ROBERT WHITAKER: Well, one of the main reasons why it happened was because Spain, in particular, the origin point for most of these letters, was going through a major period of political disruption, first caused by the Spanish-American War at the beginning of the 20th century but then also leading up to the Spanish Civil War in the 1930s. And going along with this kind of political upheaval was a favorite trick for these Spanish prisoners. They’d write their own stories, borrowing from the headlines, making it seem like they and the reader were playing a part in this political drama going on in Spain.

Another reason why this con became more common in the beginning of the 20th century was because, in particular, in Britain, you saw the publication of Who's Who. This is kind of a progenitor of modern-day Facebook, where the British elite would apply to being in Who's Who and they would share their personal details, and also include their addresses. So one of the later con artists that I look at, by the name of Vincente Olivier, used a copy of Who's Who to send “Spanish prisoner” letters to the British elite during the 1930s and 1940s.

READER: I am taking the greatest chance of my life, entrusting you such a delicate matter as this, but the strange and unfortunate position in which fate has placed me has compelled me to trouble you. I cannot count on friends or acquaintances because the majority of them became my enemies since my disgrace, and I do not wish them to know my terrible predicament, neither I know which one to trust. So I decided to trust you all my secret, depending on your loyalty and absolute discretion and imploring that you realize my situation and save me.

BOB GARFIELD: We tend to think of scams like this as something that, that bubbles up and then everybody gets wise to them, and then they just sort of vanish from the face of the earth. But no, the “Spanish prisoner” con is a steady state. Why is that?

ROBERT WHITAKER: Well, my argument is that people are attracted to easy money, but also they're looking for a good emotion, a compelling story, right? You’re receiving this letter from a desperate person, either in prison or somehow else indisposed, and it's up to you, you alone, to help them. And, you know, in many of these cases, the prisoner is not only talking about their own life but also the life of maybe a loved one, like a 14-year-old daughter. And so, I think, in many cases, it's not so incredible to believe that somebody would buy into this scam, because they get caught up in the emotions and the drama of the story presented by the criminal.

BOB GARFIELD: Bob, thank you very much.

ROBERT WHITAKER: Thank you.

BOB GARFIELD: Robert Whitaker is a PhD candidate at the University of Texas.