Should a Lake Have Legal Rights?

( Courtesy of Chuck O’Neal )

Melissa Harris-Perry: I'm Melissa Harris-Perry, and this is The Takeaway. In September 2008, the people of Ecuador voted for a new constitution, which made it the first country in the world to establish legally enforceable rights for nature. The new constitution established that "Pachamama" or Mother Earth has "the right to exist, persist, maintain, and regenerate its vital cycles, structures, functions, and its process and evolution."

In 2010, Bolivia granted nature the same rights as humans. During the past decade, lawmakers in New Zealand and India have also recognized the legal rights of nature.

Back in 2019, Ohio voters passed a Lake Erie Bill of Rights, and a 2018 documentary film, The Rights of Nature: A Global Movement, explores the relevance of legally recognizing the rights of non-animal aspects of nature.

Speaker 2: [Spanish language]

Speaker 3: Nature is no longer seen simply as an object to be appropriated, to be exploited, but begins to be seen as a subject, having rights.

Melissa Harris-Perry: This global Rights of Nature movement instantiates generations of indigenous philosophy and practice into enforceable law.

Chuck O'Neal: My name is Chuck O'Neal, President of Speak Up Wekiva, and I'm a co-plaintiff with Lake Mary Jane, suing a developer in the Florida Department of Environmental Protection for the health and well-being of the lake.

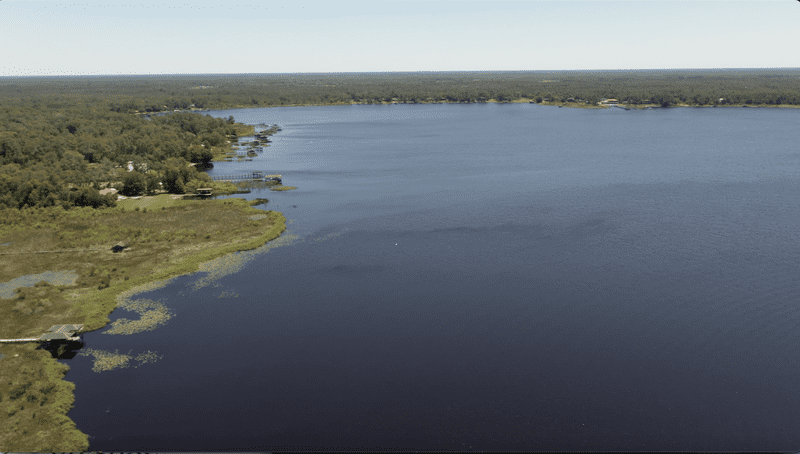

Melissa Harris-Perry: Lake Mary Jane is on the outskirts of Greater Orlando. With Chuck O'Neal as its sole human co-plaintiff, the lake is suing for its right to exist.

Chuck O'Neal: Lake Mary Jane is a fairly good size lake that's joined by Lake Hart through a canal. It's a fairly shallow lake. I believe at the bottom is possibly 13 feet deep. There's a great park on the lake called Moss Park, and it's surrounded by a small number of houses around the northeastern portion of the lake.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Chuck O'Neal first encountered the Rights of Nature movement in 2013. That same year, he started a conservation organization, Speak Up Wekiva. The organization's goal is to defend natural environments under threat in Florida, and he says that Lake Mary Jane as a natural entity provides life to a thriving wildlife and ecosystem.

Chuck O'Neal: There are a number of different wildlife that depend on the lake. There's an island in the middle of the lake called Bird Island, and any time of the day or night, you'll see droves of birds, flocks of birds coming in and out of that island. There are numerous kinds of fish in the lake, as well as alligators, otters, you name it. It is full of wildlife, and every bit is much alive as any corporation.

Melissa Harris-Perry: In 2015, O'Neal's organization sued the state to stop the first sanctioned Florida black bear hunt in 21 years. Now, the lawsuit was not successful, but in 2019, O'Neal proposed an amendment to the Orange County charter, which would give rights to natural bodies of water in Orange County, and the amendment eventually made its way to voters as a ballot initiative in 2020.

Chuck O'Neal: The charter amendment established four rights, which were the right to exist, the right to flow, the right to be protected against pollution, and the right to maintain a healthy ecosystem.

Melissa Harris-Perry: The voters of Orange County pass the amendment with 89% of the vote. Like the 2008 Ecuador Constitution, Orange County's charter amendment allows anyone to take legal action on behalf of natural bodies of water in the county, and is now the legal basis for Lake Mary Jane's lawsuit against the proposed development project, which will convert 1,900 acres of the surrounding wetlands into homes, office buildings, and lawns.

Chuck O'Neal: Just north of the lake are forested wetlands that feed filtered water into the lake, developers want to pave over a hundred acres of those wetlands and build houses directly abutting the wetland streams. This is going to impact not only the quality of water flowing into Lake Mary Jane but also the quantity of water flowing into it.

Melissa Harris-Perry: O'Neal says, because the lake is already relatively shallow, any further reduction of water flowing into the lake will threaten the wetlands, fragile ecosystems, and wildlife there.

Lake Mary Jane and O'Neal are suing two defendants in the case: Beachline South Residential, the developer of the project, and the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, which issues the dredge and fill permits that the project requires. Now we were unable to contact the developer for comment on the case, and the Florida Department of Environmental Protection said that, "The Department does not comment on pending litigation." Instead, they forwarded to us a copy of their motion to dismiss the case, which we will make available on our website.

Chuck O'Neal: In our case, in Orange County, we created and bestowed this lake with these four rights. It's not rights of personhood, so to speak, but there are rights for, I like to say, naturehood for the lake to be the lake, for the lake to be able to function as a part of nature as it should. This is what the Orange County voters voted upon. This is what they passed, and this is what we believe sets the right tone for water bodies within the United States, for them to be able to function in their own capacity, in their own abilities, wherever they are, and not be destroyed or polluted or drained to the extent that they are no longer functioning ecosystems.

Melissa Harris-Perry: We're going to take a quick break, but when we come back, we'll continue our conversation about the legal rights of nature in Lake Mary Jane in Florida. Stay with us.

[music]

Welcome back to The Takeaway. I'm Melissa Harris-Perry. We've been talking about Lake Mary Jane in Orlando, Florida, which is a natural entity, that's filed a lawsuit in a US court to protect its right to exist.

Joining us now is Steven Meyers. He's a lawyer based in Orlando, Florida, representing Lake Mary Jane in court. Steven, thanks so much for joining The Takeaway.

Steven Meyers: Thank you for having me.

Melissa Harris-Perry: You were suing, or Mary Jane is suing for the right to exist, to flow, and to be protected against pollution, and to maintain a healthy ecosystem. Are these rights instantiated into either state or federal law for the lake?

Steven Meyers: They're actually in our Florida Constitution under the natural resources provision Article 2, Section 7, and we also believe that Orange County has the right to sue under the state constitution, under the home rule provision.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Help us to understand how a lake brings suit. What's the role of the co-defendants and the role of you as the attorney?

Steven Meyers: Well, back in 2020, the Orange County Charter Review Commission passed a clean water initiative, a County Charter Provision, which is the Orange County Constitution that gave the rights to all Orange County water bodies to have the right to exist, to flow, and to be free of pollution. Shortly after that provision passed, Beachline, LLC, the defendant in this case, applied for a permit to pave over 115 acres of wetlands out off near the beach line, which would affect at least five different water bodies, which are the plaintiffs in our case.

We sued Beachline Development, the developer, and we also sued the State Department of Environmental Protection, because the State DEP actually issues the wetlands permits now in Florida, which would allow the developer to pave over these wetlands.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Okay. Help us to understand the reasons that many progressives have been quite critical of the language of corporations as persons, suggesting that persons should be as we think of them more traditionally, people who can in fact have opinions, is there a possibility that by rephrasing or reframing personhood to include natural but inanimate beings like lakes, rivers, mountains, that we create a circumstance where you could have basically people, bringing lawsuits on behalf of almost anything, rocks, blades of grass that you've cut too low, anything like that?

Steven Meyers: No. We hear this argument all the time. What we're doing is we are giving legal rights to nature, and you brought up the point about corporations. I can create a corporation on my cell phone in about 15 minutes, and that corporation now has the right to bring a lawsuit, sue or be sued to make political contributions, that sort of thing.

Rights of nature is really primarily in the legal context, just an opportunity for people to defend nature, just like they could defend a corporation, just like an estate can bring a lawsuit, even though an estate is not animate in any sense. It's not some big, scary thing. We hear, well, all these different water bodies and entities and types of natural entities could start suing people but the reality is, first of all, you have to have some enabling legislation like we do in Orange County.

Secondly, there has to be an actual case in controversy. You have to have the resources to actually hire experts, hire lawyers, marshal your evidence together. These are not easy things. They're typically very complex, and frankly, very expensive things to do.

Melissa Harris-Perry: I want you to say a bit more about this notion of the failure of regulations versus the potential involved here with Lake Mary Jane and other bodies of water, other natural entities, having rights. Why is it, in your opinion, potentially more effective for those legal personhood arguments than these regulation arguments?

Steven Meyers: Sure. Let's just start with what's the condition of our waters in Florida currently, and specifically, in Orange County. This started as an effort to protect the Wekiva River and the Econlockhatchee River, two iconic rivers in Orange County. Once it got into the charter review, and the charter review committee started looking at things, they learned that in Orange County, almost every significant lake and river is classified as impaired. Every single one by the state's own system. That means they have inappropriately large levels of nitrates, lead, coliform bacteria. Those sorts of things.

The starting point I think is that our current regulatory system at the state level is a complete failure. We're not even getting into the horrendous toxic algae blooms that pour out of Lake Okeechobee that are wrecking our estuaries and our coastlines. The fact that we have now thousands of manatees starving to death in the intercoastal waterways, which biologists, by the way, say are no longer sustainable, meaning they are in a point where they're collapsing to the point where they can't sustain life.

Our own Lake Apopka has been dead for years. Lake Okeechobee is effectively dead. The state and local governments have spent about $280 million or so, unsuccessfully attempting to clean and restore Lake Apopka.

Our water bodies in Florida are in a state of critical collapse, and yet we keep doing the same thing. We have a state regulatory agency where most of the control over the pollution of these water bodies is under the auspices of the state Department of Environmental Protection, who ironically, were in court two weeks ago, defending the developers, bringing all their power and might to the courtroom to try to enable the paving over of 115 acres of pristine waterways in Central Florida. The system doesn't work, and it's proven not to work for decades. That's why we need rights of nature and a different philosophy and a different legal approach to protecting our waterways.

Melissa Harris-Perry: How optimistic are you about the case?

Steven Meyers: I have reasonable optimism. I want to be transparent. We're trying to make new law in one sense. On the other hand, we also have very solid basis under Article 2 Section 7 of the state Constitution and the natural resources provision for the judge to rule on our favor. Essentially, what that says is that Florida laws shall make adequate provision to protect our waterways, to abate water pollution. We can prove easily that those laws are not making adequate provision to protect our waterways. All we have to do is look at the state's own system. We see that they're all impaired. We're reasonably optimistic that we will be able to move this case to the next level which would allow us to present proof.

Melissa Harris-Perry: If your reasonable optimism turns out to be right, and you win the case, what could this mean?

Steven Meyers: We have now given hope to other people throughout the State of Florida, the whole United States, and actually the world, that they can enact similar types of local legislation and hopefully at some point, a state constitutional amendments or even federal constitutional provisions, which give protections to water and other ecosystems, and that we can start changing the philosophy and our laws in the way they view our natural world, so that we have a system in which we can defend waterways and other natural ecosystems, and not be entirely dependent on state regulatory agencies to do so, which have proven to be complete failures.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Steven Meyers is a lawyer based in Orlando, Florida, representing Lake Mary Jane. Thanks so much for joining us, Steven.

Steven Meyers: Thank you. It was a pleasure.

[music]

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.