Serving Up Social Justice

Kai Wright: I’m Kai Wright and this is the United States of Anxiety. A show about the unfinished business of our history and its grip on our future.

[sounds of tennis match ending with cheers]

Announcer: A point to end it. Naomi Osaka wins her second US Open Championship.

Naomi Osaka: It's quite sad that 7 masks isn't enough for the amount of names.

1968 Commentator: There was a furor in this country over a threatened boycott by negro athletes. Then most of them decided that participation in the Olympics would further the cause of civil rights in this country.

Jackie Robinson: The only thing that we're demanding is that we be allowed to move ahead just like any other American citizen.

Announcer: Welcome, your world champions! The defending world champions!

Correspondent: Up until about ten minutes ago, we thought we were going to have a game.

LeBron James: This is a walk of life. When you wake up and you're black, that is what it is. It shouldn't be a movement. It should be a lifestyle. This is who we are.

[music ends]

Kai: I'm Kai Wright and this is The United States of Anxiety, a show about the unfinished business of our history and its grip on our future. This weekend and what will probably be remembered as one of the great moments in tennis. Naomi Osaka won the US Open in a stirring come from behind victory. She had arrived for the match wearing a face mask, bearing Tamir Rice's name. She wore seven different masks during the tournament, each with the name of a person killed an anti-Black violence. Osaka is just one among many, many high-profile athletes who are now willing to literally wear their politics on their sleeves.

Most professional sports leagues, they're dominated by young, Black talent. They are the players, the stars, the source of billions of dollars in revenue, and yet the teams and the leagues in which they play and the huge range of companies that profit from that play too, these are overwhelmingly white. That weird imbalance has always begged uncomfortable questions, questions that are not typically a welcome part of the discussion on game day. Sports are after all meant to entertain us, to be a diversion from the reality of our daily grind.

Now in all these big leagues, racial politics are suddenly as front and center as they are in the rest of society, an unavoidable and explicit part of watching any big sport. It feels to me like it's just on a scale without precedence. For this week's show, I hit up a friend and a colleague who's been preparing for this moment his whole life. Hey, Dave, are you there?

Dave: I am here. Hello.

Kai: How are you doing? Dave Zirin is a sports columnist and host of the podcast Edge of Sports. He's the longtime sports editor at the Nation Magazine and author of several books on sports and politics. He's written about Muhammad Ali, John Carlos, Jim Brown. Dave, the point is you have been a prolific man on this particular topic, but before we get into the politics of it, I want to talk to you about the game itself. It's, as I said at the opening of the show, it's been an exciting week of sports and weekend in sports. What stood out to you? What lit you up as a fan this week?

Dave: What lit me up as a fan this week was Naomi Osaka. Losing 6-1 in the first set to Azarenka and then coming back. I play tennis so, I wrote on Twitter that I want Naomi Osaka backhand for Hanukkah, this work of art and watching her play was such a joy. To know that her politics was informing her play and in such a fundamental way, like she had those seven masks, she wanted to get through all seven rounds of that tournament. She wanted to be able to represent each and every step of the way.

I got to tell you, Kai, there are so many people who said, "Oh, Naomi Osaka, she's distracting herself from the goal of winning, and shouldn't that be what sports is all about? Politics is a distraction and they don't belong in the locker room because it takes away from team spirit and unity and all that stuff that we're told from the time we're in Little League. Naomi Osaka showed that no, you can actually stand up for something and bring home the trophy.

Kai: It intensified her focus it sounds like. How many years have you been covering sports, Dave?

Dave: Since 2003 so that's 17 years.

Kai: A long time you've been doing this. In all those years, have you seen a moment you'd compare to this one? The NFL played the Black National Anthem Lift Every Voice and Sing at the start of its games today. Have you seen a moment like this one?

Dave: Not only have I never seen a moment like this one, I've talked to John Carlos, who was one of the people in 1968 who raised his black-gloved fist on the medal stand in Mexico City, and he has never seen anything like this either. I think we're dealing with history without a compass. I think anybody who says they know where this is going, should not be believed.

I think we should look at this as we should write in pencil, not pen, because we might need to erase our conclusions about what's taking place because we are in pioneer land. We are in trailblazer land. Athletes are doing things that they've never done before. They're using their cultural capital in a way like we've never seen in the history of sports.

Kai: Is there a moment that surprised you? Is there something where you're like, "Now that I thought I would never see?"

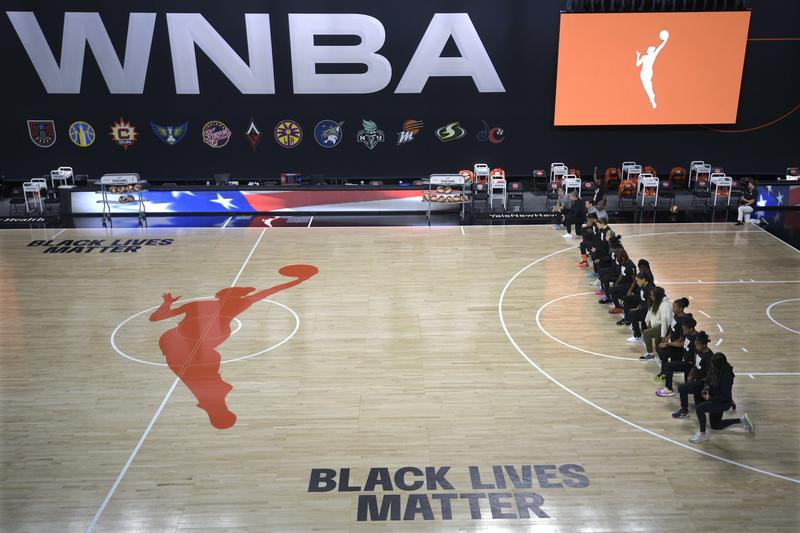

Dave: Yes, absolutely. I never thought I would see Major League Baseball take inspiration from a strike for Black lives that was being put on by the NBA and the WNBA two weeks back in response to the shooting of Jacob Blake in Kenosha, Wisconsin. When that happens, I was inspired. I was glad that the NBA and WNBA were doing it. The idea that Major League Baseball would say, "We should do that too."

That the Milwaukee Brewers said, "We should do that too." Baseball is such a conservative sport. The previous week in Major League Baseball, the big debate was whether or not a young player should have swung at a 3-0 pitch in the ninth inning, because that was seen as showing up to his opponents. There was this big debate about whether or not that broke the cardinal rules of baseball.

A week later, the players are like, "You know what, we're going to go on strike for racial justice." I got to add one last thing on that. The thing that was the true shocker, like already my jaw's on the floor. The thing that then brought me to the horizontal position on my floor was seeing that the spokesperson for the Milwaukee Brewers was a star pitcher named Josh Hader, H-A-D-E-R.

Josh Hader was almost drummed out of the league in 2018 when it was found that he had had a bunch of racist tweets in 2011, and he had to go on a big apology tour and all of the things like that and people doubted his sincerity. It was a big mess. Now here it is 2020 and Josh Hader is actually leading the charge on the Brewers to say, "You know what, the games can not go on."

Kai: I'm going to ask you to look at this in both directions here, let's start with what you are dreaming about, what could possibly come out of all this. You're excited, you're clearly excited. What do you think genuinely could come out of this activism?

Dave: I think the number one thing that can come out of this activism is that it can give-- Frankly, let's start by looking at what I think this activism has already accomplished because then I would argue what I'd like to see is the furthering and deepening of these accomplishments. The first thing is that by these players, and I'm talking specifically about the players going on strike for racial justice, not just Major League Baseball and football, but also the National Hockey league, Naomi Osaka bowed out of her tournament, Major League Soccer didn't play and they accomplished three goals that I thought were incredibly impressive for the time.

First and foremost, they recentered the conversation about Jacob Blake and police brutality and they did it. Remember, at the tail end of a Republican National Convention that was going on and on about how anarchists are going to take over your home and squat in your backyard and set fires to your swing set. The fact that they were able to actually center the conversation where it should be centered was an incredible accomplishment. Second is they brought the question of labor into the Black Lives Matter movement.

This idea of striking for Black lives, this idea, the labor movement--

Dave: Because they're workers.

Kai: Yes, because they're workers in this context and they withheld their labor as a strike. Some people called it a boycott. It was not a boycott. It was a strike and that's an incredible contribution, especially because I would argue that the labor movement has been dormant during this period of uprising since the police murder of George Floyd, very dormant. Then the last thing that they did, which was so important is I think they gave people a sense of hope because I've spoken to a lot of folks coming out of this summer of demonstrations are looking around and asking, "What did we really change?"

Here you have a situation where they said, "Well, maybe we can enact change through the ability of mass action." I think if they deepen those things, if they deepen that, keep the conversation centered where it's supposed to be, keep bringing up the question of labor and what it can do, and keep amplifying the fact that people are still demonstrating. People are still fighting for justice. I think that's just an incredible gift to all of us.

Kai: This is what we're going to talk about for the rest of this show, because it really speaks to a core question, when they get to the point where they really have to start giving things up where they really have to sacrifice, is that going to be sustainable? What's interesting about all of this is that we have in the world of sports right now, just a bit of a case study in what it's going to take to make meaningful change, which the question I've heard more than anything else is as Dave just said is over the past few months, is something in this moment of awakening of race consciousness, is it real? Is something really going to come out of it?

History suggests it will depend heavily on how those of us who have something to lose are willing to sit in discomfort. White people, rich people, men, anybody who benefits from the status quo, which is a lot more of us than we care to admit. What are we willing to give up? How long are we willing to endure the tension that real change requires? Maybe what's going to happen in sports leagues in these coming months will be a kind of harbinger of what's going to happen in society at large.

Dave is going to be with me throughout the hour, both as we talk about the potential and the pitfalls. A little later, we're going to talk about the history of sports activism and its impact on Black political consciousness, and we're going to take calls from all of you, so get ready. Dave, first before we do all that, Renee Montgomery, who plays in the WNBA for the Atlanta Dream made headlines this summer when she announced she was skipping this season and dedicating her time to activism. We're going to meet her after the break, but can you just quickly set her up for me, who is Renee Montgomery in the NBA, her career, and her role in the league?

Dave: Oh, my God, who isn’t Renee Montgomery? First and foremost, she was playing for the Atlanta Dream of the Women's National Basketball Association, the WNBA. She was a national champion with the storied UConn Huskies and she's been very outspoken on the question of Senator Kelly Loeffler, who's an owner of the Atlanta Dream, who's also a very right-wing senator from Georgia, who's been very outspoken against the Black Lives Matter movement. Renee Montgomery has been I think, giving confidence to a lot of people in the WNBA to say, "Why are you a part of this league if you're coming to it with this kind of approach towards Black lives?"

Kai: We'll meet Renee Montgomery of the Atlanta Dream right after the break. I’m Kai Wright, this is The United States of Anxiety. We'll be right back.

[music]

Hello, Renee.

Renee: Hello, there.

Kai: First, your decision to sit out, you wrote an open letter and in the beginning of it, you tell this story that really touched me about how you had this “aha” moment about it where you called your mother while you were watching what was happening out your window in Atlanta in Buckhead. I wonder if you can quickly just tell that story here.

Renee: I was watching on the news, just like everyone else, the protests and they started downtown in Atlanta. I'm like, “Man, this is crazy, but I get it.” I got the protest, and then the protest shifted. As everyone knows, the military came in, shut it down downtown, so the protest moved to Buckhead. I live in Buckhead. For me, I was looking at the protest from outside of my window while looking at it on TV. I'm like, “What is going on?” I've never experienced it in my life.

I've obviously seen it, different documentaries and things of that nature but when I'm watching it live, it's just a different feeling. I do like any other human would do. I call my parents and I'm like, “What is going on? I need some help, what should I do? Should I evacuate? Should I just go somewhere?” My friends live here. I could drive 30 minutes and stay at their house for the night.

I was just calling to get advice, and then that's when my mom started telling me stories. Like, “Oh, that's just what people do when they don't feel heard, baby.” She was like, “Don't worry.” She was telling me, she was in Detroit. She was young then, but she was in Detroit during the Detroit riots. She was just telling me different things that happened in her life that I didn't know, I'm finding out for the first time at 33.

Kai: Really? You guys hadn't talked about it?

Renee: No, we hadn't talked about it. These are all stories I'm hearing for the first time. If she had told me when I was younger, then maybe it didn't resonate with me as it did as an adult but I'm pretty sure they just hadn't told me. Just hearing that my mom was involved in a walkout in high school, because the staff wasn't making the white students treat the Black students properly. By just hearing those things, I'm like, “This is my own mom. This is my mom that we're talking about.” It really just lit a fire in me. I would say that those things affected me tremendously, and then that led to me opting out.

Kai: Also, in your open letter you wrote about Atlanta, specifically in your relationship to Atlanta. I read into it, that it's been a special place for you, and particularly in terms of putting you in touch with your blackness in a different kind of way, which is true for a lot of people in Atlanta.

Renee: A lot of people don't know, but I moved to Atlanta nine years ago. I started playing for the Atlanta Dream three years ago, but I've been living here six years before that, which is what brought me to play for the Dream because I wanted to play where I actually lived. The WNBA lifestyle is we play in the WNBA, and at that time, I was playing for the Minnesota Lynx, and then you go overseas afterwards. You probably have two weeks in between both seasons.

I just was never here, but once I started playing for the Atlanta Dream and I got to live here and be in Atlanta, I just started to see that some of the most successful people were minorities, and some of the most successful people here were women. I was like, “Wow. This place is different. This place is different and this place is lit.” You hear about New York and it's the concrete jungle where dreams are made up, I felt very empowered as a woman being here in Atlanta. Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms is running the show down here, and she's running it.

Mayor Keisha: We have gathered in our streets to demand change, and now, we must pass on the gift, John Lewis sacrificed to give us. We must register, and we must vote.

Kai: You are not alone in that sentiment about the city. You mentioned playing for the Lynx. Back then in 2016, you and your teammates, and this was early in the politicization in sports. You and some of your teammates wore shirts that said, “Change starts with us on the front” and then they had the names of Philando Castile and Alton Sterling on the back. You guys were all fine for that back then.

Renee: It was a struggle in 2016, and it was new for everyone. It was new for us. When we were doing it, we had to talk to the coaching staff and the ownership because we didn't want to do something that put a stain on the program, the Minnesota Lynx. It's a very powerful organization, and since the fanbase shows up, it shows out, the organization treats us first class. We didn't want to ruin a good thing. We wanted to make sure that we talked to everyone, we let everyone, we had a press conference to make sure everyone knew what our shirts were all about.

[clip] Rebekkah Brunson: We have decided it is important to take a stand and raise our voices. Racial profiling is a problem. Senseless violence is a problem.

Renee: We had a police shield on the back of our shirts just to make sure that people understood we weren't protesting the police, we weren't protesting America.

Kai: Did it help?

Renee: It helped none. The police walked out on us. They didn't get it. At that time, it just wasn't an understood thing. They felt disrespected. They didn't like it long story short, and the police said they weren't policing our games anymore. It was different then and that's why I tell people, progress is a beautiful thing. I've seen it firsthand. In 2016, I was on a team that fans were confused.

The police were confused. No one understood what we were doing as a Minnesota team, and now fast forward to 2020 you see the NBA, the WNBA, they have Black Lives Matter on their shirts. That's pretty crazy in four years. If you're always looking at how far we have to go, yes, we got a long way to go. We do, we get it but we've come a long way.

Kai: What changed in sport in that time? Like, the NBA, the NFL, some of these leagues frankly, the male leagues that have been slower to come along than the WNBA and other women athletes?

Renee: I would say, what's changed is the feel of the threat, almost. I think that a lot of athletes around the world are like, “What is going on?” We've always known that things were a certain way but I think that when you just see it live on TV, obviously, I think the pandemic had a lot to do with it because we all-- Everything stopped and we're all sitting still in our thoughts. We have to think about Breonna Taylor, we have to think about Ahmaud Arbery, we have to think about George Floyd.

When you have to sit and your thoughts and think, I think it resonated with a lot of athletes, and they felt like, "This is the time. It doesn't matter about sponsorship, it doesn't matter about ownership, it doesn't matter about dollars, this is not that type of thing anymore. All that matters is the fact that we need to do something," and I think that you just saw it across the league where athletes wanted to do something, and we did.

Kai: I'm struck from the outside at least and it just seems like it’s such a concrete sacrifice you've made here. It feels like such a small window to do the things you want to do in your career. Eventually, your bodies are not going to do the things you want them to do, and then I have to say as a Black woman, I imagined too, just earning potential. What do you think you're sacrificing?

Renee: I stand to lose my career. To what you're hitting at, farther time is undefeated. Everyone knows that as an athlete, you have a window where you're going to be athletic. Your skill-set can always be there, but your athleticism will die off at a certain point. We know that as athletes. I'm blessed to make it to 11 years. A lot of athletes don't even make it past four or five, that's the normal lifespan. I'm sitting at 11 with the opportunity to do 12 next year.

Commentator: A new WNBA record, Renee Montgomery.

Renee: Having said all of that, the game I love, I still feel like it was very worth it to opt-out. I'm thinking about, "Wow, this is amazing. What's going on in sports. I hope we can prolong this moment." I think about, can you imagine, like once we're four years past now and we look back at what's going on in 2020, can you imagine how far we will come? Like 2020 is changing everything. In the WNBA right now, there's a game about every other day. Every team is playing just about every other day.

Kai: We don't think about that. It's a lot of work.

Renee: That's a lot of work. This year in the Wubble is a unique circumstance. I don't know if people know, but the WNBA season has the same amount of games, but a shortened amount of time. For me, it would already been hard under regular circumstances and the WNBA to try to do all the things I'm doing now. Now with this condensed season and the Wubble, there just really wouldn't have been time.

Kai: Which is to say, it's not just about making a statement to sit out, you're doing activism, you're doing work instead.

Renee: I have a whole Moment Equal Momentum campaign. My mom was a college professor for 30 years. She helped me basically break down what my thought process was. I'm like, "I want to just change people's thoughts," and she was like, "All right, you can go education," and we broke it down. I have a campaign. Remember the 3rd of November and the Last Yard where, there are two things that are close to me, the voting campaign that's going on right now, everybody, we can't have 60% of people voting like in 2016. We need higher numbers than that.

Then the Last Yard is an HBCU initiative where I think HBCUs, they need to get advanced in tech, in the tech space and be innovative with coding and the minority communities were way behind in that. Those are two areas that I want to focus on.

Kai: Let me ask you about that specifically. Part of it is, and as I understand it also, you're specifically raising money for Morris Brown, which is a historically Black college in Atlanta. What does that have to do with George Floyd? What does that have to do with the death of George Floyd? Why HBCUs?

Renee: I'm glad you asked that because a lot of people probably wonder that. For me, everybody's looking for solutions right now and I don't have the solutions. I don't know how to fix police brutality. I don't know how to fix the prison systems right now. I don't know how to fix the health systems right now, but I know how to build and create a good environment and cultivate. I was just thinking, "So what can I do in the immediate time right now while we're trying to figure everything else out?"

I'm like, "Let's just build. Let's just help." That's how I got to the while police brutality is breaking down the Black community, I'm looking to build it up on the other end so that Black and Brown kids can go to these HBCUs. Honestly, white kids can go to the HBCU, but I want those HBCU to have the same appeal as the big D1s, to have those tech spaces, to have that coding, to have that esports program. That's my goals.

Kai: It's really striking. There's so much conversation about our deficits as Black people. Particularly in these moments, we think of so much about ways in which we oppose Black, people are unopposed. It's just interesting that you've taken this moment to, as you say, instead build Black power, to build Black agency.

Renee: Exactly.

Kai: Before I say goodbye to you, what scares you in all this? Listen, I'm hopeful some days, I'm terrified some days, I'll be honest. I hear so much hope and determination in you, where’s the part where you're not sure about?

Renee: There's some people that don't want anything to change. As we're talking about all these changes that we want to happen to America and all these cultural shifts and all these perspective changes, you got to think there's some people that love America right now and love how things are and love the racism and love the injustice. The more strides that we make to get to an equal playing field and an equal platform, there's going to be other people on the other side making bold gestures, going to a protest, and shooting people, just to make a point and that's what scares me.

There's so many things that need to change, that I don't want to just sit around and wait to see how are we going to fix things. I want to be involved in doing something right now.

Kai: That was two-time WNBA champion, Renee Montgomery, who has chosen to sit this season out entirely so she can devote her time to racial justice activism. Coming up, we want to hear from you, if you're a sports fan and you've been watching this, how has the Black Lives Matter movements showing up inside the sports you watch, how has that changed or shown up in your conversation about the game? 646-435-7280. Again, 646-435-7280. I am with sports columnist and Edge of Sports podcast, host David Zirin.

Dave, you have written that we should all be wary of any hard and fast analysis about where this is headed. You said it earlier in the show, but let's try to look at some history for examples of where it might head.

Dave Zirin: Sure.

Kai: You coauthored John Carlos' memoir of his activism. As you mentioned, he was one of the Black track and field athletes in that iconic image from the 1968 Olympics in which they stood with their fists raised in solidarity with the Black Power movement. Tell us about what were the consequences of that for John Carlos and Tommie Smith? What did John tell you that they lost because of that?

Dave Zirin: They really did lose everything. These were amateur athletes, that's the way the Olympics operated in '68. You could not make money from external sources. You were in a position where your only hopes for any making a living by being a world-class track and field star would be to get then get a job, say, as a coach, or get a job with the United States Olympic Committee, something like that. This was an entirely different kind of operation for John Carlos in his life after raising his fist because those avenues were cut. Here he is, this world-class athlete, somebody who was once timed running the hundred-yard dash in nine seconds flat.

He found himself on the outside looking in of any opportunity or anything he could do with that talent. He suffered, his family suffered. He couldn't find work. He told me a story once of having to take an axe to a table in his house so they would have firewood so they would stay warm. He worked a lot of low-income jobs and there's no shame in that, but it was a sacrifice that he had to make. The gap between Olympic glory and then what he had to do with his family was very difficult. Then this is a very difficult part of John's life, but of course, his first wife, she took her own life after a few years.

Obviously, there are myriad reasons why something that horrific would take place. He does in his own mind link it to the pressures that they were under after 1968.

Kai: What do you think they achieved as a result of this? What do you think came out of it?

Dave Zirin: One thing is certain. Again, I'm going to quote John Carlos on this. He says that a lot of folks from 1968, that the people who have regrets aren't him and they're not Tommie Smith, they're the people who were there and did nothing. They're the people who have regrets. The people who were part of those Olympics, even 50-plus years later, they're asked the question, "Hey, were you supporting those folks who raise their fist?" and they have to say "No," they weren't.

John believes, and I know for a fact that Colin Kaepernick believes this too, that John sees himself as a gardener, as a horticulturist, as he puts it, somebody who is planting the seeds for what we're seeing today. Sure enough, like I'm doing a book right now where I'm interviewing all these young kids who took a knee after Colin Kaepernick and did so in 2016. These are people who are like, even now, like they're 20 years old, 21 years old. They referenced John Carlos and Tommie Smith.

There's one girl who took a knee with her softball team. She talked about how that when she and her friends who were both taking a knee, they would walk into class. Their history teacher would say, "Hey, look, it's John Carlos and Tommie Smith. Thank you for gracing us with your presence." What they achieved, which is so important is a touchstone that says it's possible to resist as an athlete. It's possible to bring the politics of resistance and as a Black athlete, you can raise a fundamental question.

I'm quoting from their documents that was put out. Their organization was called the Olympic Project for Human Rights. They said, why should we run in Mexico City only to crawl home? That statement to me is at the heart of why so many Black athletes are protesting right now. To put it in another way, why do you love us with the uniform on but don't care about our lives when the uniform's off?

Kai: I'm talking with Dave Zirin, sports columnists, and host of Edge of Sports podcast about the past, present, and future of racial justice activism inside the world of sports. Let's go to Tom in Bensonhurst. Tom, welcome to WNYC.

Tom: Hi, good evening, guys. I'm excited to ask Dave's Zirin a question because he's one of my very favorite writers, but Kai-

Kai: I'm glad we could make the match.

Tom: -Wright, first, if I may, I'd like to ask you a question. I called in the show two weeks ago and I spoke about how the Republican Party has been almost nothing but corrosive and racist and murderous for 60 years.

Kai: I remember you, Tom.

Tom: I noticed online that they censored that call when they put The United States of Anxiety, the recording or podcast online, they completely censored that call. I don't know if that was you or if it was your bosses. Can you reinstate the call? I don't understand why you would want to censor your listeners, especially when we're talking honestly about racism in this country.

Kai: Actually, Tom, we cut that call from the podcast because we were asking for Republicans to call in and your answer wasn't from the perspective of a Republican. Thank you for your call and thank you for calling back again. Do you have a question you want to give to Dave?

Tom: Can you reinstate the call? Why would you want to censor what happened on the show from your listeners--

Kai: I'm going to let you go, Tom. I'm sorry about that. Let's go to Michael in Office Park, New Jersey. I'm sorry, Cliffside Park, New Jersey.

Michael: Hello.

Kai: You're welcome to WNYC.

Michael: I think it's great that Black Lives Matter started. The only thing is, I think they're only looking at it from one side and you got to look at things at both sides. 4,600 people were shot in the city of Chicago, 95% of them were Black, 763 of them died from their wounds. Now it's good that they're showing, with this police brutality or something, it's good to expose it. The thing is more Black people, as the mayor of Atlanta said, "More Black people are being killed by Black people than by cops," and nobody ever brings that to the attention of the public. That's all they keep saying the police, the police, the police. Look, on 4th of July weekend, 200 people were shot in Chicago. Hello?

Kai: Yes. Can I ask you a question, Michael?

Michael: Let's do both sides.

Kai: First of all, can I ask you a question just about first off in the world of sports. If you're watching sports, are you saying that you want to hear a wider range of conversation from athletes?

Michael: I want to see the athletes say enough killing. I don't want police brutality. I don't want Black people killing Black people. I'm sick and tired of seeing the pictures of Black babies, Black children being gunned down by these gangbangers and nobody ever brings it up. It's enough with the killing. I don't want to see any more killing done by the police, and especially by Black people mass-murdering, committing a genocide against Black people and that's what's happening.

Kai: I'm going to let you go, Michael. Thank you for calling. Dave, I think in that, you hear something that I do want to put to you. As people who are engaging with sports, they show up with a wide variety of political perspectives in the first place, this argument about both sides that you're hearing from Michael there. That's something we've heard in the political realm. We've heard conservatives, we've heard Republicans try to advance that idea in reaction to a Black Lives Matter argument as though that they are somehow separate things.

That somehow that has to be either or you can't value Black life in all realms. I guess the question that begs is, is sports a place where you can have the level of sophisticated conversation that this topic requires, or is that a dumb way to think about it?

Dave: It's not a dumb way to think about it and I'll resist talking about what a ridiculous canard it is. The whole concept of "Black-on-Black violence" is a ridiculous reactionary and racist canard. I also won't point out the number of African-American athletes who do work in poor communities, and that's what they are. They're poor communities where this violence takes place. Doing this work that's completely unheralded to try to talk to young people about not picking up guns, about not hurting one another.

I mean, that work happens in the world of sports. I think what sports has the power to do is to start conversations and that doesn't mean athletes have the capacity, the ability to finish conversations but they can start the conversation. They can start the conversation that happens in your house. They can start the conversation that happens with your father-in-law who might have a different political bent than you. Gee, I wonder who I'm talking about. I'm talking about myself.

It's one of those things where because of sports, I can talk to my father-in-law about Black Lives Matter in a way that if it wasn't for sports, and he's a huge sports fan, we wouldn't have that common language to even broach the discussion. We would all just be manning our respective political barricades. I think that's what sports has the capacity to do. I think that the discussions that have started out of the athletes doing this is actually incredibly healthy for this country.

Kai: Let me ask you about that, your own story there with you say sports allow you to talk to your father-in-law. Where did this start for you? Where did this idea that sports is a great place to start to begin political conversations come to you?

Dave: There was an explicit moment but then looking back, there was also a subconscious moment. I think for me, I grew up in New York City in the 1980s and '90s and that was the time of Yusef Hawkins. That was the time of Bensonhurst. That was the time of Howard Beach. People probably know what these instances refer to, racist killings and the city felt so divided and so on edge, and I was a basketball player. I would go to the courts, and I would be part of a culture playing basketball that other people I knew who were white were not a part of.

Therefore, they also weren't privy to how Black and brown people were speaking about what was happening in terms of Howard Beach, Crown Heights, Bensonhurst. That was a huge eye-opener for me politically, of just understanding that my views as a white person, in my perspective, were not the be-all and end-all of how the world worked. Then when I was in college, there was a basketball player named Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf of the Denver Nuggets, who made the decision to not stand for the flag.

Then his remarks about why he made that choice was so political and so smart and so deep and so informed by his own intellectual journey that, that just absolutely exploded my mind because I was a huge sports fan, and all of a sudden, here I am seeing this athlete bring the politics of dissent to the world of sports. I just thought to myself, "You know what, this is something I want to write about and explore."

Kai: Let's go to Fran in New Rochelle. Fran, welcome to WNYC.

Fran: Hi, thank you. Thanks for having me on the show. I was very moved by everything that's been said so far. Unlike Dave, I'm not as connected with sports now as when I was young, and a boy. I'm now a transgender woman. I don't find that I'm as connected with sports, but I can say that I was very moved by a dribble march, which was Black Lives Matter march that happened in New Rochelle last Saturday. I was invited to attend it. I walked down the main street of the town. It was the first Black Lives Matter march I was in.

I walked down with a group of about 80 mostly Black people dribbling basketballs and it was very peaceful. There were sayings and slogans that were said during the March, but I was very much impacted by how loving and smiling everyone was, and I felt like I was finally connected to the movement which I felt in my heart. I've gone on to set up a Zoom program in October, called judging people unfairly where we're going to explore this in more detail.

I think that my white friends and family who are avid sports fans seeing that they need more of an opening of their heart, and I agree with Dave, is that it could be done through conversation. It doesn't have to necessarily be sports-driven but in my case, being part of that dribble march was the catalyst that got me to really feel more deeply about my connection to doing something positive for other people.

Kai: Thank you so much for that call. Fran, I hope you'll call back. Dave, I want to get to your thoughts on Muhammad Ali within all of this because you have written a book about Muhammad Ali as well and when we talk about conversation starters, he seems to sit at the center of it. You have called him, "The most important athlete ever to live" which is strong words. Why was he so important in this conversation?

Dave: Muhammad Ali was so important for the simple reason that he had one foot in the Black freedom struggle and one foot in the anti-war movement against the war in Vietnam. This was at a time when those two movements were actually on different tracks. I mean, towards the end of the '60s, they came together, and you saw the Black Freedom struggle inside the anti-war movement, but the anti-war movement started very white and you saw Muhammad Ali though, as the most famous athlete on Earth. Literally the physical embodiment of bringing those two movements together, that's his importance.

I also think he becomes this very helpful touchstone for understanding what's happening today. I was asked the question about Colin Kaepernick and comparing him to Muhammad Ali and, and I said, "One thing that's very similar is that when Colin Kaepernick took that knee in 2016, he was very much alone on an island, only a couple other players did it as well. Now by 2020, he's really regarded by athletes as a prophetic voice." Muhammad Ali, similarly, when he said he wasn't going to fight in Vietnam was the most despised athlete in the country.

It only took a few short years for the country to actually be on Ali's side. That wasn't because of his individual charisma. That was because the country itself had turned against the war in Vietnam. There's a way in which Ali's relevance is something that stays with us to this day.

Kai: I love a quote I saw on one of your columns. Ali said, "Some people thought I was a hero. Some people said that what I did was wrong, but everything I did was according to my conscience, I wasn't trying to be a leader. I just wanted to be free."

Dave: I love that quote. I also love his quote, when he joined the Nation of Islam, he was asked, "How can you do this? You're supposed to be the heavyweight champion, you shouldn't be joining this organization." He said, "I don't have to be what you want me to be." I think that slogan could be applied to 2020 and these athletes as well.

Kai: Quickly, who do you see as the Ali or the John Carlos of today, of 2020?

Dave: Naomi, Osaka. Let's go full circle. The fact that Naomi Osaka would enter this incredibly country clubs sports, which is dominated by Whiteness, from the uniforms at Wimbledon, to the people who play and walk in there, and say, "Not only is this who I am, this is what I'm going to represent." By representing the politics of Black liberation, it's actually going to make my game stronger. That to me has a tremendous echo of Muhammad Ali.

Kai: Dave Zirin, who is host of Edge of Sports and a columnist, a sports columnist and sports editor of the Nation Magazine, author of several books on sports and politics. Dave, thanks for joining us.

Dave: It's my pleasure. Thank you so much.

Kai: Something else we're doing here on the show is we're thinking about what brings us joy. As I worked on this episode, I have to share what brought me some joy. I did not know that Muhammad Ali almost won a Grammy in 1964. He had an album of poems, so it was actually when he was still called Cassius Clay, and his poem, I am the Greatest was nominated for Grammy as a comedy album. It's not as political speech, but you also just can't take away this man's ability to dance with words and I just love it. I want to play it for you. Check this out.

Ali: Yes, I'm the man this poem is about.

I'll be champ of the world, there isn't a doubt.

Here I predict Mr. Liston's dismemberment.

I'll hit him so hard, he'll wonder where October and November went.

[laughter]

[applause]

Kai: That was Cassius Clay on his Grammy-nominated album in 1964. A little bit of joy for you to start the week. That kind of wordplay, it's fun too. He went on as Muhammad Ali, to change the world in all kinds of ways, and to pave the road for the kind of sports activism that we're seeing today. Thanks to all you sports fans for hanging out with us this evening. I hope whatever team or player you're behind wins. I am definitely here for Naomi Osaka's US Open victory. Listen beyond sports, we've asked our podcast subscribers to send their own stories about something they've been willing to give up or a stress they've been willing to endure as they stand up for racial justice.

I'd love to hear from all of you, as well. Just record a voice memo and email it to anxiety@wnyc.org. That's anxiety@wnyc.org. United States of Anxiety is a production of WNYC Studios. Engineering help this week from Jared Paul, George Wellington, and Matthew Marando. Kevin Bristow was at the board for the live version. Our team also includes Carolyn Adams, Emily Botein, Jenny Casas, Marianne McCune, Christopher Werth, and Veralyn Williams.

Our theme music was written by Hannis Brown and performed by the Outerborough Brass Band. Karen Frillmann is our executive producer. I'm Kai Wright. You can keep in touch with me on Twitter @kai_wright that's K-A-I Wright like the brothers. And if you can join us next week for the live show, I hope you will. That's Sundays at 6:00 PM Eastern. Stream it on wnyc.org. Or tell your smart speaker to play WNYC. Until then, thanks for listening and take care of yourselves.

[music]

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.