BOB:This week, the White House held a three day Summit on “Countering Violent Extremism.” Its aim was to forge a multi-pronged strategy to counter extremism of all forms. But the focus on the Summit has been on language: politicians and pundits alike have been harshly critical of President Obama’s choice of words when describing acts of violence perpetrated by ISIS and its affiliates.

MARC THIESSEN: We are not at war with violent extremism…We’re at war with Islamic radicalism. And you cannot defeat an enemy if you won’t even name it.

GREG GUTFELD: This is a very easy way to look at this. They are terror denialists. They deny terror at every place.

BOB: Indeed, the President has been condemned, by both the Right and the Left, for refusing to use words like “Islamic” or “jihadist” in his remarks on acts of terror. Scott Shane is a national security reporter for the New York Times. Shane says that the latest bout of presidential censure is a long-standing political problem.

SHANE: The labeling goes back to the beginning of the Obama presidency when an army psychiatrist named Nidal Hasan had a shooting spree at Fort Hood and killed 13 people, and former Vice President Dick Cheney took Obama to task for not calling that out as Islamic terrorism. There's always been, on Obama's part, a reluctance to put the religious label on acts of terror or indeed radicalism. And there's a logic to that, but I think many Republicans and some Democrats and some counter-terrorism officials at this point would say perhaps the logic has gone a little bit too far.

BOB: The logic being, I guess, that to the extent that each of these acts is characterized as a jihadist act of terror or an Islamic act of terror, it helps spread the narrative that the West is engaged in a cultural war with Islam, instead of with the individuals behind particular episodes, right?

SHANE: That's right. Part of it is that words like jihad and Islam have a huge authority in the Muslim world, and to hand those labels over to Al Qaeda or to ISIS, to affirm that what they call jihad is in fact a jihad in religious terms, would be a real problem and that's why the Obama White House has been very careful not to say that. And that does receive a lot of support certainly in the American Muslim community, but also among a lot of counter-terrorism folks, they say you're in a war of ideas, in a battle of ideas, and you certainly don't want to suggest that Al Qaeda and ISIS are Islam. You want to treat them as a murderous criminal offshoot that falsely claims the cloak of religion, as opposed to conceding that they represent the religion.

BOB: The problem is that shouldn't we all be able to keep two apparently opposing ideas in our head at the same time? One, that terrorists and extremists like ISIS do not represent Islam and its billion some faithful worldwide, but to also hold in your head the notion that they are themselves acting in what they perceive to be the interest of Islam. If you don't acknowledge both, isn't there kind of disingenuousness that the Republicans have seized on?

SHANE: I think that's the problem that has come up and it's partly because us in the media naturally grab for the common sense label that conveys to readers or viewers what an incident is about. So if someone at Fort Hood yells "Allahu Akbar" and shoots up a lot of people and is Muslim and when you look at it seems to have been considering whether attacking his fellow soldiers would be a religiously justified act of jihad, we immediately label that as Islamic radicalism and so on. When everybody else in the discussion, notably everybody in the media, is using these labels of Islamic and jihadist, and the White House is not, it makes their language sound evasive and pallid by comparison. And once that framework is set up, you know, they kind of can't win.

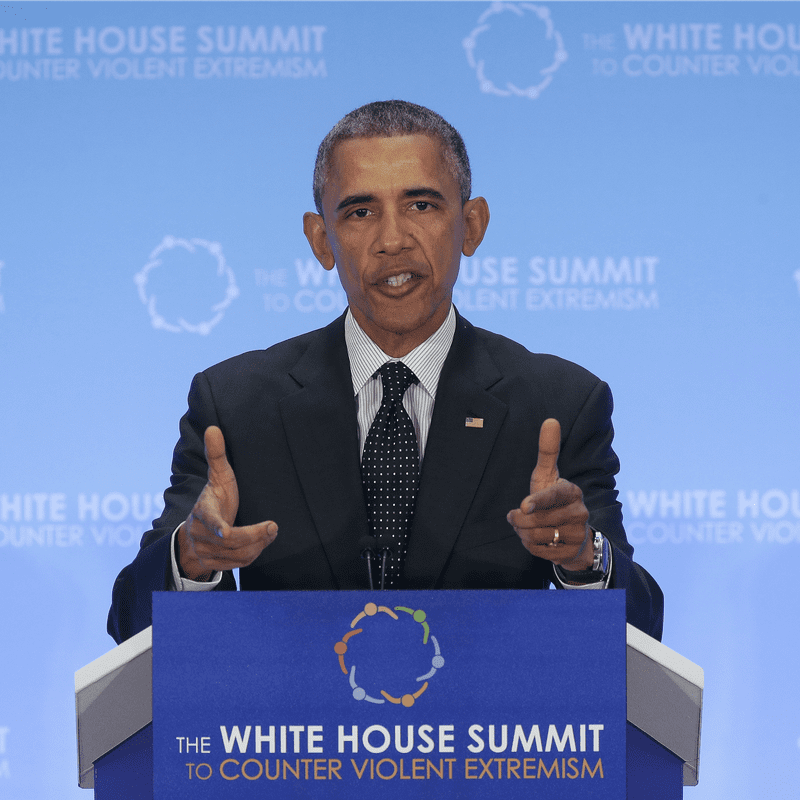

OBAMA: Leading up to this summit, there’s been a fair amount of debate in the press and among pundits about the words we use to describe and frame this challenge...

BOB: Here was the president on Wednesday describing the quandary that he is in:

OBAMA: We must never accept the premise that they put forward, because it is a lie. Nor should we grant these terrorists the religious legitimacy that they seek. They are not religious leaders — they’re terrorists.

BOB: It's understandable, Scott, that the president does not want to give oxygen to terrorists and their perverse ideology. There is the question, though, of what his responsibility is to the American public. Michael Flynn, a retired Army lieutenant general, who ran the Defense Intelligence Agency from 2012-2014, said the president does have a responsibility which he doesn't believe he's meeting. This is him speaking at a House hearing last week:

FLYNN: You cannot defeat an enemy that you do not admit exists. And I really, really strongly believe that the American public needs and wants moral, intellectual and really strategic clarity and courage on this threat.

BOB: Is Flynn right? Does the government have to acknowledge the threat in order to defeat it? Or is actually the opposite true?

SHANE: You know one of the folks that I talked to about this, Akbar Ahmed, who's a professor and chair of Islamic studies at American University, said that there had come to be what he called a "scholastic" feel to some of Obama's language. And that he thought that was a problem. And he said that he came across as sort of making ivory tower distinctions, and that he need to get down into the hurly burly of politics. And several people I talked to about this problem recognize that the White House has a dilemma, but they thought that you could resolve it by saying that this is a strain of Islam that the vast majority of Muslims reject, as opposed to using very generic words like violent extremism and ignoring the claims of ISIS and Al Qaeda, however unjustified.

BOB: So if the president has to worry about all the different ears listening to every word he utters, is there any sense, particularly in the midst of this summit, which ears he's most concerned with?

SHANE: For the most part this is a purely domestic political issue, but the fact is that some of the Muslims he has to avoid offending are much more important than just a relatively small group of ordinary American citizens, and those are leaders of countries, some of which are now our allies in the fight against ISIS. And certainly other places in the fight against Al Qaeda, and many of these leaders regularly say when there are acts of terrorism by Al Qaeda or by ISIS, 'This is not Islam.' Part of what motivates Obama is that he does not want to appear to be labeling this stuff that his allies have said is not Islam as Islamic. So part of what's going on here is any president speaks to an international audience of great importance in addition to his domestic audience.

BOB: Scott, thank you very much.

SHANE: Thanks, Bob.

BOB: Scott Shane is national security correspondent for the New York Times.