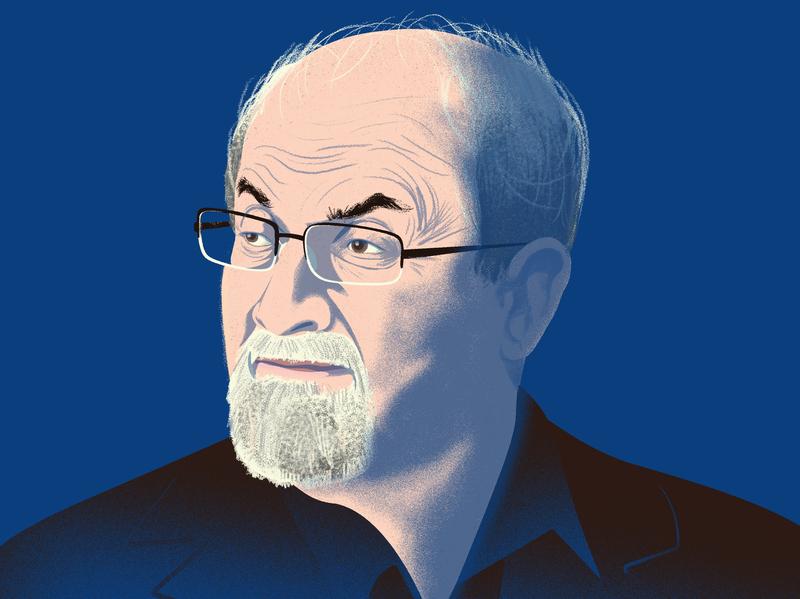

Salman Rushdie on Surviving the Fatwa

[music]

Intro: This is The New Yorker Radio Hour, a co-production of WNYC Studios and The New Yorker.

David Remnick: This is The New Yorker Radio Hour. I'm David Remnick. [music] 34 years ago, Ayatollah Khomeini, then the Supreme Leader of Iran, declared that a novel called The Satanic Verses was a blasphemy. He issued a ruling, a fatwa, ordering the assassination of its author, the Indian British novelist Salman Rushdie. After 10 years of fugitive life in London, and then more than 20 years living freely, and unguarded in New York City, history caught up with Rushdie.

History came in the form of a young man named Hadi Matar, dressed in black, and wielding a knife. Matar attacked Rushdie on a stage in August, stabbing him repeatedly, Rushdie barely survived. First, I need to ask how you are, just how are you feeling?

Salman Rushdie: I've been better. [laughter] Considering what happened, I'm not so bad. As you can see, the big injuries are healed, essentially. This had a knife injury in the middle of it.

David: Do you have feelings in your left hand?

Salman: I have some. I don't have feeling in my thumb and index finger, and in the bottom half of the palm.

David: Can you type?

Salman: Not very well, because of the lack of feeling in the fingertips. The big injuries was here.

David: It's right into your right jaw and neck.

Salman: Yes. On the neck, and up around here, the right side of my face. There was a lot there. There were chest wounds, and the liver was injured.

David: Do we know how many times you were stabbed?

Salman: I wasn't counting [laughter] at the moment anyway. I've read different articles which have had different numbers.

David: How the hell would they know?

Salman: I don't know. Maybe they asked the hospital. I think there must have been somewhere between 15, 20. Again, I only know this from reading the newspapers, but apparently, he had 27 seconds before people jumped on him. That's how much damage you can do in 27 minutes.

David: The hell, it's 27 seconds. It's a hell of a lot. [music]

This is the first time that Salman Rushdie has spoken publicly since the attack. We're going to spend all of The New Yorker Radio Hour today with him, talking about the fatwa, and the near assassination 33 years later. We'll also talk-- This is what he was most eager to do, about literature, about storytelling, starting with his new novel, Victory City, which comes out this week.

Salman: Actually, it's just a piece of good fortune, given what happened. I had actually finished the last bit of editorial work on it. I'd actually had corrected the galley at the end of July, two weeks before.

David: Unbelievable.

Salman: We had the jacket. We actually were beginning to get the blurbs. Everything was ready.

David: Are you concerned that Victory City would be read through the prism of what happened in August?

Salman: Well, I'm hoping that, to some degree, it might change the subject. I've always thought that my books are more interesting than my life. Unfortunately, the world appears to disagree. [chuckles]

David: Your life is--

Salman: Interesting?

David: Yes.

Salman: What I'm hoping is that, people will be able to say, "Oh, he is a writer." I've tried very hard not to adopt the role of a victim. Then, you're just sitting there saying, "Somebody stuck a knife in me, poor me."

David: You don't feel that way?

Salman: Which I do sometimes think. [laughter]

David: It hurts.

Salman: It hurts. What I don't think is, that's what I want people reading the book to think. I want them to be captured by the tale, and to be carried away, and to enjoy being in it, and to want to know what happens next, and to read a book.

David: I remember that line of, I think it was Martin Amos's line that, "Salman has disappeared into the-- Vanished into the front page when the fatwa happened." It's happened again. Let's go beyond the front page. You say you finished this extraordinary novel-

Salman: Just before.

David: -one month before. Tell me a little bit about the history, the origin story of Victory City.

Salman: What had happened, it actually began, thinking about this book really a long time ago. It was very hard to find the voice for it. That's often the way with me. Even when I know what the story is and so on, to find the right door to go into the story, it sometimes takes me a few attempts.

David: Then, you feel the garbage can a bit?

Salman: Yes, I just get it wrong. I start, and sometimes the place where I started, actually, belongs in another place in the book. It's just not the beginning.

David: What was the case with this?

Salman: When I found out, I read something about this little kingdom, where the women had all committed Sati.

David: Self-sacrifice, ritual suicide.

Salman: There is some historical record of that event. It's not exactly as I've portrayed it, but something like that happened. Then my little nine-year-old girl stood there watching it. I thought, "Okay, now I know whose story it is."

David: That young girl became the heroine of Victory City. She's named Pampa Kampana.

Salman: It's one of the things when I've been teaching this strange craft that I have said to students, is the first question you need to ask yourself is, whose story are you telling? Then, you have to ask yourself a "why" question. Why are you telling a story? What's the story?

David: How did you answer the "why" question here?

Salman: For me, in part, it was just a pleasure of world-building, just having a chance to create a big canvas on which there would be-- That the book would also be about somebody who was building the world. It's me doing it, but it's also her doing it.

[music]

David: Pampa builds the world of the story, magically. She has been given a divine power, a bag of seeds to sow an entire city into existence. Now, ever since he published Midnight's Children, his first really great novel in 1981, Rushdie has written Wonder Tales, stories that mix the fantastical, and the historical, and the setting of Victory City is in fact, historical. What he's written is a fable about the founding and the fall of the Vijayanagara Empire in South India, in medieval times.

Salman: A lot of people in India know very little about the Vijayanagara Empire. Yet, for 200 years, it was running most of South India. I remember thinking then, maybe one of these days, I got to pay attention to South India, being myself from North India. I'd had it, and I'd been--

[crosstalk]

David: This is like a New York boy wanting to write a southern novel, isn't it? You're a Bombay boy.

Salman: Yes, or even Manhattan boy wanted to write about Brooklyn.

[laughter]

David: That distant.

Salman: It took 15 years for you to find-

[crosstalk]

David: This is the seed, it just gets planted.

Salman: -the story. What happened is that this girl, my main character, just showed up, she just showed up in my head. I have no idea where she came from.

David: When you say it shows up in your head, we all know from our rock and roll history, Keith Richards having a dream and-

[crosstalk]

Salman: Having the Satisfaction written.

David: -of the Satisfaction written. I don't imagine it's quite as easy as that.

Salman: No, look, here's the thing, the Vijayanagara Empire, it seems to have come out of nothing. Let's just say one minute, it's not there. There's lots of other kingdoms. The next minute, it's the most powerful thing in the place. Just dying like that. I thought that's very strange.

David: For an American reader, you've talked about this a bit before, most American readers are steeped in the tradition of realism. I forget whose analogy this was. Maybe it was [unintelligible 00:09:27] or something like that, that there are two big streams of fiction.

Salman: Yes, it is [unintelligible 00:09:31]

David: You're of the other kind. Which is to say, fantasy and fable, and this is what you grew up reading.

Salman: Yes. I also think that it's just another way of telling the truth.

David: Tell me about that.

Salman: Put it like this, the first kings of Vijayanagara announced quite seriously that they were descended from the moon. The reason they said this was, in the ancient Indian myths in the Ramayana, and the Mahabharata, there are heroes who are supposed to be part of what's called the Lunar Dynasty. That's to say the moon God is their ancestor. When these kings Hakka and Bukka, announced that they're members of the Lunar Dynasty, they're basically associating themselves with those great heroes. It's like saying, "I've descended from the same family as Achilles." I thought, "Well, if you could say that, I can say anything." [laughter]

David: As a storyteller.

Salman: As a storyteller.

David: In other words, the didactic or polemical elements of this, the way some readers, I think mistakenly read novels sometimes is the, "What's my takeaway? What's the news here?" That comes last.

Salman: Yes. No--

David: It's a story, it's the fantasy that you've dipped your cup into the river of story.

Salman: Yes, but there are things about reading about the empire that were very surprising. For example, that the role of women was quite advanced, and that women were allowed, were able to be things, which even today is difficult. There were women generals, there were women lawyers, there were women merchants, there were women doing everything for long periods of time, not always. There were some periods which were more repressive. I thought that's interesting, that this is the 14th century.

David: Is there some point in the writing of a text where the character-

Salman: Takes over.

David: -takes over?

Salman: Completely. She told me how to write it and how it should go, and she really did. I just thought, "Oh, you know exactly what you're doing. I just follow you." She just opened the book up. One of the things I really have-- There was this history professor called Arthur Hibbert, who was one of the geniuses of his time, but he said to me this thing, he said, "You should never write history until you can hear the people speak." He said, "Because if you can't hear them speak, you don't know them well enough, and you can't tell that story."

David: It's a novelist's--[crosstalk]

Salman: I thought, "What a great piece of advice for a novelist." It always stuck with me and been helpful.

David: That happens in the thinking, or it happens in the daily writing-

Salman: It happened in the daily writing. [crosstalk]

David: -pushing all up the hill.

Salman: Daily writing. Some of it is history. There are things in there that, people in there who existed. I don't quite give them--

David: Come out of the bibliography that you provide and--

Salman: Yes. The Hakka and Bukka were historical characters. They weren't quite as I have described them, but they were the first two kings, and they were brothers. I've just taken liberties.

David: Well, why not?

Salman: Why not? [chuckles] They're not going to object. In many ways, been true to the spirit of what was happening then. There were periods of great bigotry, and there are other periods of great openness. I just wanted to say, "Look, this is the history of India. It's not what the BJP says it is."

David: This is a point that's quite important to Rushdie. The BJP is India's ruling party, the Hindu Nationalist Party of Narendra Modi, and that party frames Indian history as one giant battle between Hindus and outsiders, Hindus and Muslim invaders. Good guys versus bad guys.

Salman: It's much more interestingly complicated and confused, and messed up. What people are being interested in, is not just what God you worship, but who's in charge? It's about what public life is about. It's about politics, it's about power, it's about treachery, and all those things which are much more interesting than sectarianism, and to try and reduce Indian history to that sectarian description, first of all, it's wrong, but secondly, it's not interesting. [chuckles]

David: Also, I think it's also what's about many things, but one of the things it seems to be about, and I don't want to over torque on the timing of its publication and what's happened in the last year, but it's an insistence on the permanence and importance of storytelling, as opposed to the impermanence and vanity of the powerful.

Salman: Yes. I think and India knows this because these stories, the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, they're thousands of years old, and yet everybody still knows them. There was a television series made from the Mahabharata that ran for years. It had audiences like 300 million people. [laughter] Then, there's a very famous line of comic books in India, which take the stories of antiquity, and turn them into comic book stories, and so children grow up knowing these stories by reading comics, not by reading the actual original texts.

David: When's the last time you were in India?

Salman: Seven or eight years ago.

David: Is that a possible thing to do?

Salman: Everything was possible until this happened, and now I don't know quite--

David: You don't?

Salman: I don't know about whether I can go anywhere, and I'm just-- Well, put it like this. It's not about whether I can or not, it's whether I'm ready to or not. I'm not thinking long term, I'm thinking short term.

[music]

David: Salman Rushdie, he completed work on the novel Victory City just weeks before the attempt on his life last August. We'll continue in just a moment. This is The New Yorker Radio Hour.

This is The New Yorker Radio Hour. I'm talking today with the novelist, Salman Rushdie. This is the first interview Rushdie has given since an attack that nearly killed him last August. A number of his books came up as we talked, that I'll mention here, Midnight's Children and Shame, two novels about the subcontinent. The Satanic Verses, of course, which is mostly set in London, and a memoir that he wrote about the fatwa, called Joseph Anton, which was a code name he used while living in hiding. Rushdie's new novel is out this week, and it's called Victory City. You're writing it in a particular years. In the last five years, I don't know how long it took to write.

Salman: I got a three.

David: You're writing in the Trump years. You're writing in the Boris Johnson years. You're writing in a time of illiberalism, to say the least, in India, your three countries of greatest concern. How much is that impinging on the novel?

Salman: Actually, the three previous novels had all dealt with that stuff, about what's happening to us, not just in America, but as you say, all over the place. I just thought, "Enough already." I think I've looked at that really for years now, and I had this desire to go back to the beginning, go back to the kind of storytelling, the kind of book that made me fall in love with books, and to return to that place of love and write a book out of that.

David: What do you think is this stylistic or aesthetic path you've traveled from Midnight's Children to Victory City? How do you, when you stand back and look at your own work?

Salman: I think it's interesting. There's a language thing that's changed., That's say when I started out with Midnight's Children and Shame, and to some extent, even with The Satanic Verses, I was deliberately trying to find something in English that sounded un-English. I remember reading about Joyce trying to colonize the language back, to have an Irish-English, instead of an English-English, like Derek Walcott made a Caribbean English and, of course, America, because America was a colony too.

David: I remember.

Salman: [laughs] You were there.

David: Yes, I was.

Salman: American writers, of course, have made many Englishes, and I thought, "I want to do that. I want to find a way."

David: I just want to locate it consciously before heading into Midnight's Children you made that determination?

Salman: Yes. Because I was very lucky when I was at Cambridge that one of the people I met a few times was E. M. Forster. I met him three or four times, and he actually said something which I treasured, which is that, he said he felt that the great novel of India would be written by somebody from India with a Western education. [laughs]

David: You felt it was a blessing?

Salman: I felt it was, yes, thank you. What I rebelled against was Forsterian English is very cool and meticulous and so on. I thought if there's one thing India is not, it's not cool.

David: It's hot.

Salman: It's hot. It's hot and noisy and crowded and excessive. How do you find a language that's like that?

David: You found that in Midnight's Children, God knows. What I'm asking you is, what's the stylistic path to Victory City?

Salman: Well, what happened is, at certain points, I thought I have done that enough. Certainly, by the time I wrote The Satanic Verses, even by then, I thought, "I don't need to do that anymore. I've done that."

[music]

David: This is The New Yorker Radio Hour, I'm talking with Salman Rushdie. The publication of The Satanic Verses in late 1988, changed everything for him. The fatwa was announced. Rushdie went into hiding in England. Several people associated with the book, translators and publishers in other countries, who were easier to find, were attacked, some even killed.

After a decade though, in 2000, Rushdie moved to America. He began going out, appearing in public, he took a very visible position as the President of Pan American Center, which champions freedom of expression for writers and human rights. One of the things that's so sobering to remember now, is just how many people in the West were really hostile to Rushdie at the worst time.

As I wrote my profile in The New Yorker this week, some people behaved well, but some people behaved disgracefully. Cat Stevens, John le Carré, Jimmy Carter, the Archbishop of Canterbury, the British Foreign Secretary, they all criticized Rushdie in one way or another just as he came under the fatwa, an outrageous and bloody-minded decree. They implied, to one degree or another, that he had brought this nightmare on himself.

Salman: Well, there was a moment when there was a "me" floating around, that had been invented to show what a bad person I was.

David: How would you define the "me", the Salman Rushdie that you've just described?

Salman: Evil, arrogant, terrible writer. Nobody would have read him, if there hadn't been an attack against his book, et cetera. There was a false self that was floating around. I've had to fight back against that false self.

David: Were you forgiving of it? The litany of names of people who behaved badly, and said stupid things at best in the--

Salman: Yes, I remember some of them. My mother used to say that her way of dealing with unhappiness was to forget it. She said, "Some people have a memory, I have a forgettery."

[laughter]

David: You?

Salman: I think as I get older, I'm beginning to develop that.

David: You came here to the States, and you did an amazing thing, you assertively decided, "I'm not only going to live, I'm going to live three years in every year."

Salman: One of the things I thought is, there were often-- People were scared to be around me. I thought the only way I can stop that is to behave as if I'm not scared. I remember being in a restaurant in East Hampton with Andrew Wiley, taking me out to dinner, Nick & Toni's, and Eric Fischl came by to say, hi, to Andrew. Then, he looked at me and he said, "Shouldn't we all be afraid and leave the restaurant?" I said, "Well, I'm having dinner. You could do what you like."

[laughter]

David: That almost seemed somewhat, I remember there's a piece in The Times at one point years ago, you're going out, you're doing this, going ballgames, dancing, whatever the hell you were doing, and it was almost a censorious tone.

Salman: Yes, people didn't like it, because I should have died. Now, that I've almost died-

David: They love you.

Salman: -everybody loves me. I was told afterwards, when I became conscious again, that there had been this great outpouring of support and affection, which I'm very grateful for it. I'm not aware of it, I didn't see any of it. My impression is that, suddenly, everybody's on my side, [chuckles] and thank you.

[laughter]

David: We talk a little bit-- Let me ask the horrible question. I think at some point, one of your books you say this, "Security can never be absolute," or some better version of that. Do you feel that you made a mistake in living freely?

Salman: Well, I'm asking myself that question, and I don't know the answer to it. I did have more than 20 years of life. Is that a mistake? Also, I wrote a lot of books. The Satanic Verses was my fifth published book, my fourth published novel. This is my 21st.

David: It is interesting to remember that. That's true. It's a relatively early book.

Salman: Three-quarters of my life as a writer has happened since the fatwa.

David: You wouldn't have traded it?

Salman: No, in a way, you can't regret your life, because, without your life, you wouldn't have had your life.

David: One of the amazing things, and you say it in so many words in Joseph Anton, and you live it, is that you refused to let the fatwa impinge on your imagination, your imaginary life, your writing, but that was a real determination.

Salman: It was. I just thought there are various ways in which this event can destroy me as an artist. One way is that, I should be scared, and that I would write scared books, or not write.

David: What's a scared book?

Salman: Well, a book that doesn't tackle anything important. That shies away from things because you worry about how people will react to them. That's a scared book. A lot of them are around these days. I'm too old for that. The other way it could really wound my work was, if I wrote vindictive books. If I wrote revenge books, because both of those make me a creature of that event. I lose my individuality.

This is my 21st book. I don't know how many there's left, but there's not another 21. I've done my work, and I've been very fortunate, in that, I've found really quite a wide readership, which pays the rent. I've been quite lucky in the way. I had a hit a very big bump in the road with The Satanic Verses, but in general, and go back to your earlier point, people do seem to have got the point of this writing. Whether it's in England or America or India, enough people have got the point of it, to allow me to be a writer.

David: Fatwa was a bump in the road, which is an eloquent way to put it. What is this imaginatively? In other words, no, the event and the way it impinges, or not on your reader as an artist?

Salman: Well, what it is, is something I'm going to have to write about.

David: In the mode of Joseph Anton?

Salman: Well, not in the third person, I think. I've done feel third-person-ish to me. I think when somebody sticks a knife into you, that's a first-person story. That's an "I" story. [laughter] What I'm thinking now, which is, this is my germ on the way to the book is, that one of the things that my books have tended to be, is panoramic. They've tended to be like widescreen, with substantially large cast of characters, sometimes multigenerational, and sometimes set in many places, what Henry James used to call a loose, baggy monster.

David: Big, shaggy monster. This can't be panoramic is what your kind of choice.

Salman: What I'm saying is, the kind of book I haven't written, is the book which focuses on a microscope, and makes the universe from it. Mrs. Dalloway, having a dinner party. The people who write books, where they can take to see the world in a grain of sand.

David: You do that, the idea would be to do it imaginatively in great measure-

Salman: I don't know.

David: -or documentary, because if it's so brief-

Salman: How do you spread-

David: -and you're in the hospital for six weeks. If I look at the clips, there's very little there.

Salman: There's very little there, but there's a lot-[crosstalk]

David: The kid seems to be--

Salman: An idiot. I don't know what I think of him because I don't know him. All I've seen is his idiotic interview in The New York Post, which only an idiot would do. I know that the trial is still a long way away. I guess I'll find out some more about him then. I've always tried to find a thing to do that I haven't done. Why I'm saying this writing about this event in this way is that, that gives me an artistic reason to think about it, to try and do something I've never done, which is a small frame from which you create the world.

[music]

David: Salman Rushdie, speaking about the knife attack that nearly killed him last August, and the book that he might write someday about that. My profile of Rushdie covering all this ground and more appears in The New Yorker this week. This is The New Yorker Radio Hour. More to come.

[music]

This is The New Yorker Radio Hour. I'm David Remnick. In this week's New Yorker, I wrote a profile of Salman Rushdie, which you can find at newyorker.com. Just before Christmas, Rushdie and I sat down for a long interview at the office of his literary agent, Andrew Wiley. This is the first time he spoken publicly since he was attacked.

The assailant was a New Jersey man named Hadi Matar, who parroted the claims of Ayatollah Khomeini that came out more than 30 years ago, claiming that Rushdie was an enemy of Islam, and that his novel was a blasphemy. Rushdie suffered multiple injuries, and he lost the sight in his right eye.

Salman: I'm able to get up and walk around, when I say, "I'm fine," there's bits of my body that need constant checkups. It was a colossal attack.

David: In your days now, obviously, you're not writing, you're not at a desk eight hours a day, and you're doing some physical therapy. Your days are spent how?

Salman: I'm trying to slowly get back to a writer's life, and I'm-- Reading, trying to write.

David: You can read?

Salman: I find it easier to read on an iPad, because it's lit, and because I can affect the size of the type. I've been reading more on an iPad than actual books.

David: How's your endurance? How's just your ability to get through the day with sleep and--

Salman: It's getting back. I've always had, my great gift is sleep. I can always sleep. There have been nightmares, but not--

David: Of the incident?

Salman: Not exactly the incident, but just frightening, and those seem to be diminishing. We haven't really talked about it, but there is such a thing as PTSD.

David: How has that played out for you? What is it?

Salman: It's a number of things, but one of the things it is, is that I've been-- Found it very, very difficult to write. I sit there to write, and nothing happens. I write--

David: It's like terrors, it's blankness.

Salman: It's a combination of blankness and junk, should stuff that I write that I delete the next day, there's been a lot of that. I'm not out of that forest yet, really.

David: You blame anybody?

Salman: I blame him. I think, I'm here now, and I'm always been, one of the ways in which I've dealt with this whole thing is to look forward and not backwards. What happens tomorrow is more important than what happened yesterday. My main overwhelming feeling is gratitude.

David: Who saved your life?

Salman: A number of people. There were doctors in the audience, who came and did immediate stuff, waiting for the helicopter and then--

David: If you got stabbed in the neck that you didn't bleed out is something--[crosstalk]

Salman: There were people putting thumbs over it.

David: You were saved by a thumb?

Salman: Yes, somebody's thumb, and then the helicopter, and then this extraordinary team of surgeons. There was a seven, eight-hour surgery. There's a lot of me that was just lucky, because the amount of injuries was such that, it was more probable that I would not survive. It was a very close thing. It was a very close thing, but fortunately I came out the right side of the close thing.

I haven't wanted to talk to a journalist for four, it's just over four months, and you can't imagine or if you can imagine the amount of journalists that have-

David: I can.

Salman: -wanted to-- I just thought not ready, and to be able to come here to talk about books, to talk about this novel, Victory City. To be able to talk about the thing that most matters to me.

David: That you're here to do.

Salman: That I'm here to do. With this one, as you said, first of all, I get more and more interested in the pleasure principle. That the purpose of art is to bring joy.

David: That's extremely evident here.

Salman: I think it was a book that--

David: You thought otherwise earlier in your life.

Salman: I thought so, that's not the heart of it. When I started out, I guess, Midnight's Children in Shame really were an attempt to deal with the world that I'd come from, and to try and make it artistically mine. The Satanic verses was about, what it's-- It's a novel about London, it's a novel of thinking, "Well, okay, now I've dealt with where I came from. Let's talk about where I came to," and so I was thinking about that thing. Now I'm just thinking about joy.

David: What are you less patient with? What do you feel yourself less able to do than when you were 32 at the page?

Salman: I used to be faster. I used to write a lot more in the day, but it needed to be rewritten a lot. Now, I write much less in a day, but it's closer to--

David: That shift is a tribute to age in both senses. and experience?

Salman: I think so.

David: Or the processors work a little differently than they did before?

Salman: It just happened over the years. When you are young, you have to fake wisdom, and when you're old, you have to fake energy.

[laughter]

David: At somewhere around your age, maybe younger. I remember Updike was asked, when you look down the rear view mirror of your work, even though knowing there's more ahead, how do you assess it, in terms of what you think will last, and what you think the best of it is? Writers hate this question for obvious reasons. He was very clinical about it. He said, "Well, it's very clear. It's the X number of stories, and-

Salman: For sure, Rabbit.

David: -and Rabbit," and I think he had an affection for some other, I forget the other title. Can you answer that question?

Salman: I just hope something lasts. [laughs] You don't know, do you? I remember there was a moment, not long after the death of Anthony Burgess when--

David: Who wrote how many books?

Salman: Who wrote a yard of books, where every book he had written was out of print, except for A Clockwork Orange. If something lasts, you should be grateful. I think Haroun and the Sea of Stories might last, because when children love a book, they take it with them through their life, and that's been a book which has had the most wonderful life in the world

David: Because of its quality, but also because who it's pitched toward a little bit.

Salman: I thought there must be a way of writing, where you don't ask yourself if the book is for children or for grownups. There are movies like that. I said, if you can make The Wizard of Oz, if you can make Who Framed Roger Rabbit, if you can make The Princess Bride, if you can make Star Wars, you don't ask yourself who the audience is. The audience is everybody who likes it, and that's everybody.

I thought there must be a voice, where you can do that with a book where grownups will read it in a grownup way, and children will read it in another way. That was the hardest thing about writing that book, was to find that, I would write it, and I would think, "That's too childish." I would write it and I think, "That's too grown up."

David: You were writing it at--

Salman: At the worst moment.

David: At the worst moment, or in the second.

Salman: Yes, the moment before the worst moment. Also, I was helped by the fact that I was writing it for my son, whose middle name is Haroun. I thought this is happening to him too, and so I have to keep-- I had made him a promise that I'd write a book he would want to read.

David: Salman, you once said some years ago, or maybe you wrote it, that the great wound in your life was how you and your work were treated in India, and yet your imagination is very much lodged there. What's changed on that front?

Salman: What I can't do is, I can't do anything about it, either side of that. I can't do anything about what's happened with my work in India, and I can't do anything about the fact that I still want to write about it. [chuckles]

David: What are the circumstances for your work in India? I was at the Jaipur Literary Festival, I forget how many years ago, and you were going to come, and then you couldn't. Then, you were going to broadcast in, and then you couldn't. It was horrible to witness.

Salman: Well, look, there's a double thing in India. One is that, I have a lot of Indian readers. That's very nice. A lot of those Indian readers are young, and that's very nice.

David: They can get all your books?

Salman: Except one

David: Satanic Verses, obviously?

Salman: Yes. Which is a shame, but everything else is there. I know that when, I've been told by Kashmiri journalists and writers that when Shalimar the Clown came out, the response to it and Kashmir was very positive. It's the only book of mine which got any kind of an award in India.

David: Really?

Salman: Sold a lot of copies and was pirated.

David: Which is a better award, but, yes.

Salman: It was pirated, and the pirates sold so many copies. I have no idea how much, but your ₹10 instead of $10. The pirates started sending me greetings cards. [laughter] I would get a birthday card.

David: God bless.

Salman: I thought that really is rubbing salt in the wound.

David: Matters are getting worse there politically.

Salman: Yes, they are.

Salman: Terrible.

David: Are politics and events in India on a one-way journey to worse and worse?

Salman: Yes. Except that I never believe anything is permanent. I think one of the things about this study of history, is that it shows you that history can make enormous changes at the last minute to quote Grace Bailey's title. [crosstalk] If we had been sitting here a couple of months ago in the year 1989, and I had said to you, "The Soviet Union will not exist at Christmas." It would have seemed crazy. This thing which looks permanent and immutable and powerful, vanishes, I'm saying that the world can change-

David: Related to India?

Salman: I mean, the problem in India is this, that the current government, which to people of my way of thinking, is alarming, is very popular. It's the difference, for example, between India and Trump. That Trump was only just about popular, and his level of unpopularity was at least as high as his level of popularity. That's not so in India, because the Modi government is very popular, has huge support.

That makes it possible for them to get away with everything, to create this very autocratic state which is unkind to minorities, which is fantastically oppressive of journalists, where people are very afraid. Which in a way it's getting to be difficult to call it a democracy, because a democracy is not just who wins the election. It's whether you feel safe in the country, whether you voted for the government or not. India has a problem. The way in which this book tries to just marginally engages with it-

David: Only marginally?

Salman: -is that it takes on the subject of sectarianism, and tries to say, "This is not the history of India." The history of India is much more complicated than that. It's not that there was an ancient culture that another culture came in and destroyed. That's a false description of the past. As we know, we live in a world in which false descriptions of the past are being used everywhere to justify terrible behavior in the present.

England pretending there's this golden age before any foreigners showed up and completely ignoring the fact that they were fucking over foreigners in their countries, in order to make possible their wealth and affluence at home. America talking about being great again. I want to know when was that, what was the date? [chuckles] It was obviously before the Civil Rights Act, was it before women had the vote?

Was it when there were still slavery? What are we harking back to? A fantasy past becomes a way of justifying bad behavior today. I want to say that the history of India, I'm a historian by training.

David: You read history at Cambridge?

Salman: Yes. In the last year at Cambridge, you just choose three special subjects, and that's all you do. I did one on Early History of Islam, where I heard about an incident called the Incident of The Satanic Verses. I thought, good story. [chuckles]

David: It is.

Salman: Yes. I found out later how good. [chuckles] I did American History from 1776 to the end of reconstruction. I did Indian History from the Indian Rebellion or uprising 1857 until Independence in 1947. That's three things I studied. All three of them have featured very largely in everything I've written since.

David: That is for sure.

Salman: India-- Look, I love India in a way that you can only love the country of your birth. I always will.

David: You feel loved back?

Salman: By enough people, nobody gets loved by everybody.

David: No.

Salman: The things that I feel offended by are times when cultural gatekeepers in India have described me as not being an Indian writer. There were people who felt that they didn't-

David: Authenticity versus not.

Salman: Look, on the whole, I would have loved to spend more of my life in India. I used to go every year, every year I would go. After the fatwa, for a very long time, I was not allowed to go.

David: Salman, you got visited by-- It's still a lot that's unclear about this guy, but fanaticism certainly visited you in the most terrifying way. The same time in Iran--[crosstalk]

Salman: Amazing things happening.

David: Amazing things are happening. If you look at things, the granular almost killed you, and yet something-

Salman: Is happening.

David: -is happening.

Salman: I have nothing but huge admiration for those young women, and not all of them young, and for the men who have supported them. I worry about the Iranian soccer team, because all of them stood up for the demonstrators. Every single one of them, from the captain speaking at a press conference at the beginning of the World Cup. Now, they're back in Iran.

I don't know if they're okay. Has anybody followed the story? I haven't seen it. It's a very brutal regime. I'd like to feel it's a tipping point. I don't know. I've become very hesitant to forecast. The world seems unforecastable.

David: Would you have forecast in any way, or was it out of mind what happened in August?

Salman: I won't say that I hadn't thought about it over the years, I had. I had come to feel that it was a very long time ago, and that the world moves on. That's, I guess, what I had agreed with myself was the case, and that it wasn't.

David: Go ahead.

Salman: I have a lot to think about as a consequence of that. I haven't finished with that thinking, and I don't quite know where it comes out.

[music]

David: Salman Rushdie's new novel, his 21st published book is called Victory City. A profile of Salman Rushdie appears in this week's New Yorker. Our conversation lasted almost three hours, so we've edited and condensed it quite a bit for today's program. This is The New Yorker Radio Hour. Thanks for joining us today. See you next time.

Outro: The New Yorker Radio Hour is a co-production of WNYC Studios and The New Yorker. Our theme music was composed and performed by Merrill Garbus of Tune-Yards, with additional music by Louis Mitchell.

This episode was produced by Max Balton, Britta Greene, Adam Howard, KalaLea, David Krasnow, Jeffrey Masters, Louis Mitchell, and Ngofeen Mputubwele. With guidance from Emily Botein, and assistance from Harrison Keithline, Mike Kutchman, and Meher Bhatia. The New Yorker Radio Hour is supported in part by The Charina Endowment Fund.

[music]

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.