Russia’s Intentions in Ukraine—and America

[music]

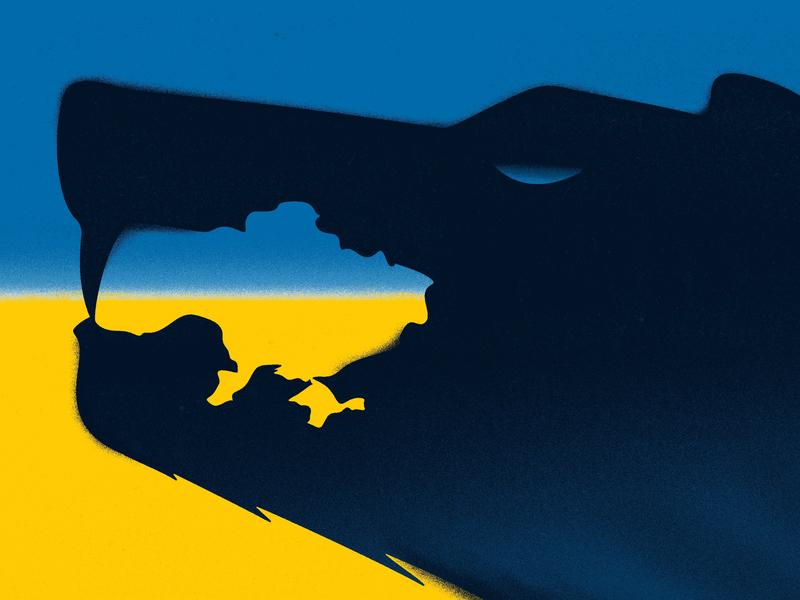

David Remnick: Throughout the long Cold War, which had consequences all over the world, the Soviet Union and the United States and its European allies somehow managed to avoid a full-on military confrontation. 30 years later, that is the prospect we face. Russia insists that the West has taken advantage of its weakness, and is now threatening to invade Ukraine yet again. It's a terrifying prospect. At this enormously tense moment, I wanted to talk with the historian, Timothy Snyder. Snyder is a professor at Yale and the author of the best seller Bloodlands. He's long studied the dynamics of this part of the world, particularly Ukraine, Russia, and the rest of Europe.

Snyder's book The Road to Unfreedom, from 2018, is a study of Vladimir Putin's effort to influence and undermine Western democracies. We spoke last week. Sometimes people seem to forget when they ask, "Will Russia invade Ukraine?" that Russia has invaded Ukraine twice already. First in 2014 to Crimea, and has occupied Crimea ever since. Russian troops are in Eastern Ukraine, they're all over Eastern Ukraine, and many thousands of people have already died. What are the stakes now?

Timothy Snyder: I think it's interesting, the way that Russia has set this up for us, because they are presenting us with this, as it were, shocking new development that they might invade a country. Then the discussion is framed about what we are supposed to do to prevent them from doing that. In that very shock, we forget that they've already carried out an illegal occupation for eight years. Interestingly, this leads us to a difference between how the Ukrainians and, let's say, the Americans react to all this, which can be instructive. The Ukrainians are the ones who are about to be invaded. They're the ones who are facing the loss of tens or hundreds of thousands of lives, of millions more internal refugees.

They're the ones who actually face that, and yet their reaction is much more low-key than ours, which I find interesting. Your question gives a reason for it. They've already been invaded by Russia. Every day, they ask themselves what Russia is going to do next. I think what that helps us to do is to see the artificiality of the situation.

David Remnick: Now, I just spoke to Masha Gessen, who's in Kiev. She said exactly what you're saying, which is that people are quite calm in an almost strange and preternatural way. She's with friends at dinner and they're far less freaked out about this than many people in the United States. Obviously, the lowest form of journalism, much less scholarship, is prediction, but let's indulge it anyway. As you look at what's happening now with over 100,000 troops amassed on the Ukrainian border, with troops in Belarus also poised at Ukraine, with all the cyber capacities that Russia has, what do you think that they will do? What is the leverage of the West?

Timothy Snyder: David, honestly, I don't know. I don't have a solid feeling for it. Last time, it was as though they jacked up the ideology, the propaganda, very effectively and then they pretended they didn't invade. This time, they jacked up the troop presence very ostentatiously. It's as though they're doing the opposite. They've made it very, very clear that they could invade and now they want to talk. I guess my thinking about that is that we have to be very aware of our own psychological reactions before we respond because they push buttons.

You have to think, "What button of ours are they pushing here? What are they trying to get us to do? What would it mean if we react to that effort at button pushing?" They're asking us to stop them from invading a country. That's a difficult assignment. You have to ask yourself, "Is it Russia's responsibility to stop us from invading Mexico?" It'd be a terrible thing if we invaded Mexico, it would be senseless. Is it Russia's job to stop us? Is it our job to stop Russia from invading Ukraine? It would be terrible for Ukraine if they did. It would be also terrible for Russia if they did.

We don't want that to happen but we can't really accept the premise that it's our responsibility, which is the button they're trying to push. They're trying to make us feel guilty in advance for the terrible war in Ukraine. They're trying to shift that responsibly unto us, which means that we then say, "Then we have to do A,B,C,D and E, we have to do all these dramatic things." What if we do all these dramatic things and then they invade Ukraine anyway? What if we do all these dramatic things, and then three years from now, they push exactly the same button?

I think our response should be more unpredictable than it's been. I think we should be meeting their proposals with counter proposals that are about completely different subjects like, "Where's your political opposition? Hey, let's work together on nuclear fusion," and a whole bunch of other things. Because what they've done is they've defined the agenda, and we are scared, we're meant to be scared. Whereas the Ukrainians are treating it like real life. It's true that Russia might invade at any moment, but that's real life and so what are you going to try to do to prevent it and what are you going to try to do to make sure you're not being manipulated by this terrifying spectre?

David Remnick: I think it's important to account for the psychology here. We're constantly talking about how Russia feels about Ukraine, how Putin feels about Ukraine, how Gorbachov did, or Shevardnadze or whomever. How do the Ukrainians feel about their neighbor, Russia, since the end of this Soviet Union in 1991?

Timothy Snyder: I think your question points to a very important issue of, let's call it rhetorical hygiene in the US. I think we really shouldn't be having discussions about Ukraine where we invite Russians or American diplomats who spent their career on Russia to talk without having Ukrainians on the panel. I think that we're very conscientious, some of us anyway, about who's on the panel when we think about our own American problems. No one should have been talking about dividing up Czechoslovakia without Czechoslovaks in 1938. No one should be talking about Ukraine's future without Ukrainians in 2022.

Interestingly, getting to your question, Russian imperialism vis-à-vis Ukraine is sharper all the time. It's not actually true, as Putin likes to say, and as people like to repeat, that there's a long history of the two countries always being together, blah, blah, blah. That's not actually true. It's not only much more complicated than that. It's much more interesting than that. What we see is a sharpening of Russian attitudes under Putin, especially in the last 10 years, about Ukraine. They've reached this point where we now are where it's clearly just imperialism, where one country is saying about another country, "You don't really have the right to exist. Your people don't really exist."

David Remnick: What is true? In other words, you're absolutely right, we hear from Putin on one level, but also others in Russia, that Ukraine is the seed of all Russian and Ukrainian civilization, Kiev and Russ and, "We were together in this period of history, we were together in this period of history, and this was a tragic loss, and this is our sphere of influence, so it's in military, in geopolitical terms." What is actually true? What is the basis for the Ukrainian reality and psychology of Ukrainianness?

Timothy Snyder: I'll give that a shot but I want to first make a disclaimer, which is that no one really gets to judge whether the Ukrainians are a nation except the Ukrainians. Those are the rules. There's a distant story, and there's a recent story. In the distant story, Ukraine is not really that different from other European nations. There is a moment of early modern proto nation formation, which actually comes very early to Ukraine in 1648 with the uprising against Poland. At that time, the word Ukraine is actually being used, and at that time you can see Ukraine emerging as something different from the people who speak a similar language to their north and now the people who are Belarusians, and also as distinct from Poland.

Russia is not really in the picture at that point. At that point, in the middle of 17th century, there's clearly a very early assertion of something like Ukrainianness. Then there's an imperial moment. In the Imperial moment, the territories that are now Ukraine are divided up between the Russian Empire and a bit in the Habsburg Monarchy. There's a very typical 19th-century national revival which begins actually in what's now Eastern Ukraine. Then, over the course of the 19th century, largely because of increasingly oppressive Russian imperial policy, ends up in Western Ukraine. After the First World War, there is, again, a very typical attempt to establish a nation-state.

Many more Ukrainians actually struggle for a nation-state after the First World War than, let's say, Czechs or Slovaks, but they're defeated because of the Red Army and the Bolshevik Revolution. Then you have this grappling on the Soviet side with what to do with Ukrainian national question. Lennon doesn't doubt there's a Ukraine. Stalin doesn't doubt there's a Ukraine. The question is what do you do with this Ukraine? It's mainly because of Ukraine that the Soviet Union is established as it is, not as some unified thing, but a nominal Federation. It's worth stressing that although in the Soviet Union Ukrainians die, sometimes by the million, because of the Ukrainian question, no one in the Soviet Union actually doubted that there was a Ukraine.

This business that there's no Ukraine and it's just brotherly nations, that is an extreme position which can be identified with contemporary Russian rhetoric, but which hasn't really been. That extreme Imperial position is actually something new and when Putin says, "I say this because it goes back a thousand years," one should just really ignore that. One could interpret the last 1,000 years in various ways, but the idea that this new Russian Imperial has somehow always been what even Russians thought is just not true.

David Remnick: Now, Russia, in many ways it suffers from a sense of weakness. Putin, most of all, suffers from a sense of weakness and the greatest defense that a Barack Obama probably gave to Russia is when he called Russia and a regional power. That was taken very hard in Putin's circles. What is it that Putin wants now? Doesn't e have enough internal difficulties with whether it has to do with his own really sinking ratings or a monoculture economy? Doesn't he have enough problems that foreign adventures, which are extremely expensive in in blood and treasure? What does he need this for?

Timothy Snyder: I tend to try to think of this in cultural rather than in personal terms because, as you know, it's very easy to get swept away by the mystique of the dictator. Then you find yourself thinking in a dictatorial or an Imperial way yourself. Structurally speaking, Russia, although of course it's a cultural superpower and it's a hugely important country in many ways, it has some self-imposed problems. The self-imposed problem is oligarchy or kleptocracy. The Putin regime is based upon the state and the oligarchs being the same thing. That has a certain functionality, but it means that you can't really have domestic policy.

If you have all the wealth concentrated in the hands of the people who actually run the country, you can't have meaningful reform, you can't have meaningful redistribution. Without the rule of law, Putin is basically, or anyone at the helm of a system like that, is stuck with spectacle, is stuck with distractions, the old bread and circus idea, but also is working from a situation where you want to bring other countries down to your level. You want Russians to think that the organized mendacity and perfidious and apparently irresistible inequality, you just want them to think that's normal. That America's the same way, Britain's the same way, the EU is the same way.

Your foreign policy is designed to bring everyone else down to your level. With that, you can understand their intervention in our elections or the way they talk about us. They want to bring out the elements of us, both rhetorically and in reality, that are most like the way they run the country.

David Remnick: Let me do it for Russia here, as a matter of our argument. If I'm in that position, the Russian position, I get to say, "You're lecturing us about interference in your elections. Haven't you done that in elections and political processes around the world? You're lecturing us about possibly invading or having invaded a sovereign country. Haven't you done that repeatedly in modern history?" What is the American answer? What is the moral retort to that, as well as political?

Timothy Snyder: I think this is a good example of that argument. That argument from hypocrisy is an example of how they try to bring everything down. They're not saying, "You shouldn't do stuff like that." They're saying, "Everybody does it." It's part of their general attempt to extract value out of all conversations of international and domestic policies. I'm happy to concede that the US should not have invaded Iraq, and that was completely illegal. I'm happy to concede that we interfered in elections in Latin America. That was a desperately wrong thing to do. I grant you that, but when I grant you that I'm granting it to you and affirming the standard.

Their conclusion is because the United States sometimes does bad things, therefore there are no rules. Therefore, anything goes. I think it's very important not to fall for that argument from hypocrisy, because of course sometimes people break rules, but when they break rules, what you do is you affirm the rule. You don't affirm anarchy, which is where their diplomats want us to go.

David Remnick: I'm talking with the historian, Timothy Snyder, the author of The road to Unfreedom on tyranny and other books. We'll continue in a moment. This is the New Yorker Radio Hour. We're talking about the crisis in Ukraine and Russia and Europe with historian, Timothy Snyder. Now, Snyder is one of the best writers I've ever read on that region. His history Bloodlands was about Ukraine and other countries that were caught between dictatorial regimes before and during the Second World War. In a book called The Road to Unfreedom, Snyder looks at autocracy in our time and at the strategic reasons for Putin's meddling in the United States and other democratic countries.

Now, when Russia invaded Ukraine in 2014 and occupied Crimea, it was supposedly on behalf of the country's Russian speaking population. Let's pick up there. Tim, help us here on what's got to be confusing for a lot of people. In Ukraine over the past 30 years, since the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991, you've had a back and forth between leaders who were pro-Russian, who want to be allied with Moscow, and with pro-Ukrainian or nationalist leaders who are seen as pr-Western or pro-NATO. This also the factor in this whole question of ethnic division and linguistic division.

When I go to Ukraine to write about nationalism in the late '80s and early '90s, certainly Western part of the country spoke Ukrainian almost exclusively. You could see how culturally distinct it was from the regions east of Kiev, which are more Russian speaking, or at least they were then. What dynamic do these divisions of ethnicity, of culture, of language, play in the current argument?

Timothy Snyder: Countries having different political orientations in different regions is not such an unknown phenomenon. If you look at Italy, for example, the south and the north are very different. I would say more different than east and west Ukraine, but it's still one country. It doesn't make Ukraine stand out and it's not an excuse for us to say, "It's not really a country." On the second question about language you're right, of course, that if you start at the far west of Ukraine, almost everybody's speaking Ukrainian and people will speak Russian, but at this point they can't really spell, they can't really write it anymore.

They will watch the TV, they watch the movies, they can speak it, but they can't really write it. Whereas, and if you go all the way to the east, you'll find people who are deliberately learning Ukrainian, but whose native language is clearly Russian. That's all true, but we and the Russians both have trouble with the idea of a bilingual country. The Russians, that's one of the buttons they push. They say, "Well, if they're Russian speakers, then they must somehow be Russians." We're English speakers. That doesn't mean we're English. The Austrians are German speakers, doesn't mean they're Germans. Then with the presidents, here's what happens with Ukrainian presidents.

You run for office on the idea that you're going to calm things down with Russia and you win on what is, in American terms, a Southern strategy. That is you appeal literally to the south of the country and you talk about cultural issues. On that platform, you win. That's how Kravchuk won. That's how Kuchma won, that's how Yanukovych won and that's how Zelensky won. Then when you're in office, you move, so to speak, west and west and west and west. You try with Russia, it doesn't work out in a more or less dramatic way. Then your second diplomatic move is to go to the west, and then when you run for office for your second term, your electorate is now in the west part of the country rather than the east part.

That's happened over and over and over again. That pattern, it's cranky and weird, but it's much more interesting and truer than to say, "Well, there are the Russian speaking ones and Ukrainian speaking ones, and there's just the east and there's just the west." It's more like that. It's a collage. Zelensky started out much more an east Ukrainian figure and over his first term, he's had to move in both senses towards the west. Zelensky went to Russia with peace proposals. As you know, Zelensky was elected to make peace with Russia by a war weary nation. Then he tried, and Putin's response was 150,000 troops on the border.

David Remnick: The president of Ukraine is an absolutely fascinating figure to me. Volodymyr Zelensky. What are his options?

Timothy Snyder: Zelensky is an interesting guy. Just to stop on a couple points about him, a former-- [crosstalk]

David Remnick: [crosstalk] turned president of a crucial European country.

Timothy Snyder: Yes. He's like some slightly better universe's version of Trump. He's an entertainer, he's a comedian. He actually made it up from the bottom as a comedian.

David Remnick: I would have said Al Franken, maybe. More generous.

Timothy Snyder: [laughs] Yes. I'm thinking also about the way they comport themselves just in terms of their comedic delivery, I meant. Zelensky is an authentically, very talented personality, hugely talented, who had a show which was called Servant of the People. Then he ran for president bringing his own fiction into reality, and won by a huge margin. One thing Zelensky is, is that he's an affirmation of democracy. Democracy brings things you don't expect. The second thing is that he's Jewish. Just worth keeping in mind because the Russians are going to pound the vulnerable sectors of German and American public opinion with this notion that Ukraine is a terrible right-wing country and make us feel bad about the Holocaust if we talk about Ukraine.

They're going to go for that. For them, the Holocaust is just a button to push and they will push it regardless of what the realities are. Then the third thing about Zelensky which is interesting is that he's a Russian speaker. There's this whole thing that Putin gives us about how they're brotherly nations, blah, blah, blah. Of course, if you don't know who your brothers are, that means you're having an identity crisis. If you confuse your neighbors with your brothers, that means you're having an identity crisis. Basically everybody in Ukraine, as you know, is bilingual to some degree or another, but Zelensky leans pretty hard in the Russian speaking direction.

The first few weeks and months when he was president of Ukraine, he was still dropping Russian phrases into his English and into his Ukrainian. He's gotten that under control a bit better now, but he was doing a lot of that. His comedy was mostly in Russian. He's a Russian speaker. Putin's idea that you have to invade Ukraine or do something about Ukraine because the Russian speakers aren't free, a Russian speaker is president. A Russian speaker could run for president. Russian speakers in Ukraine are a lot freer than Russian speakers in Russia are in pretty much every respect. A Russian speaker in Ukraine is much freer than a Russian speaker in Russia.

As far as his options, he is playing this an interesting way. He's saying the things that we've been saying, "They've already invaded once, we're prepared as well as we can be prepared. We could really use some help. Folks should help us." I think that's probably appropriate.

David Remnick: What's your evaluation of the Biden Administration so far in terms of this?

Timothy Snyder: I tend to think that this is about the Biden Administration in a pretty fundamental way. If we take a step back from NATO and we think, if your goal is to undermine NATO, let's accept that that's their sincere goal, who do you want to be president of the United States? Trump would be the United States. Trump made it pretty clear, especially in the second half of 2020, that if he was president again, he would try to withdraw the US from NATO. What is the effect of this crisis in the US? It puts Biden in a very bad position. It's very hard for Biden to look strong. At least the way that they've approached the crisis so far, they've been on the back foot.

Then Ukraine itself is an awkward issue in American domestic politics. I tend to think that, insofar as there's a strategy here, it's about dividing NATO members and about putting pressure on the Biden administration right now.

David Remnick: Maybe you disagree with me, but it seems to me that some part of this is an attempt not only to attack Ukraine, but to exploit a crisis of democracy in the United States. Not that Putin is necessarily looking at the situation in Georgia and the secretary of state and the granular details of that, but he knows, witnessed January 6th and witnessed many other things, that we are undergoing a crisis of democracy so much so that the dialogue lately, and I believe legitimately so, is in terms of civil war. A civil war of a kind, at least. Is Putin not trying to take advantage of that moment in the utmost way?

Timothy Snyder: Yes, I agree with you. On the 30th anniversary of the end of the Soviet Union, the piece that I wrote was about how the United States could come to an end and how we should be looking at the end of the Soviet Union as an unexpected systemic collapse rather than as a moment of triumph, and that the lessons of the end of the Soviet Union for us might be a little bit different than what we think. You look at this one way, and I look at it one way, and I'm sure Putin looks at it a different way, but I agree with you completely that he is thinking about putting pressure on our system, however he would define it.

For example, January 6th they pushed very hard because they love January 6th. They're big fans of January 6th. It gives them so much grist for their mill about how democracy is just fraudulent. They have a lot of fun talking about how these are just legitimate protesters and so on and so forth, and we're hypocrites because we don't let these legitimate protesters protest. I think this is exactly why we have to use this as a moment to go big and continue this idea of a foreign policy, which is about democracies and for democracies and for democracy.

David Remnick: Forgive me for interrupting, Tim, but I think what you're getting at is the possibility that in Putin's mind, insofar as we can define it, that he would like to see our December 25th, 1991, when the Soviet Union finally collapsed. He wants to see that happen in the United States in somewhere between November and January in 2024.

Timothy Snyder: Yes, of course he does. He would put it differently, but there are two things that he understands, I think, basically correctly. One is that our system is vulnerable, and the other is that democracies rise and fall together. Trying to divide NATO is also a way to weaken democracy in general. Pushing the Biden Administration up against the wall and doing your best to make sure that it's Trump who comes back in some installation, rather than an election scenario. Of course that's what they want. They're right to think that that's a risk. Their perspective can be very helpful, like that of an evil physician. He wishes you ill, but his diagnosis may nevertheless be correct. I think you're right.

This all goes back to the point I was trying to make earlier about relative success and failure. Russia can only deliver so much to its population. The existence of a democratic alternative from Kharkiv in eastern Ukraine to Vancouver in Canada, that whole thing, what they call the Collective West, that whole thing is a problem in Russian domestic politics. That whole thing, the existence of that rival, of that other way of living, more sensitive the closer it is, more successful, maybe, further away. The existence of that is a problem for a regime like the Putin regime.

It's not just they have ideological differences or they have resentments. It's also that the existence of this democratic alternative or this rule of law alternative is a problem. It's not that we threaten them by what we do. We threaten them by our existence.

David Remnick: Tim Snyder, thank you so much.

Timothy Snyder: It's been a pleasure. Thank you for having me.

[music]

David Remnick: Timothy Snyder is a professor of history at Yale University, and his books include Bloodlands, The Road to Unfreedom, and On Tyranny.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.