5 Years of Deadly Violence Against the Rohingya

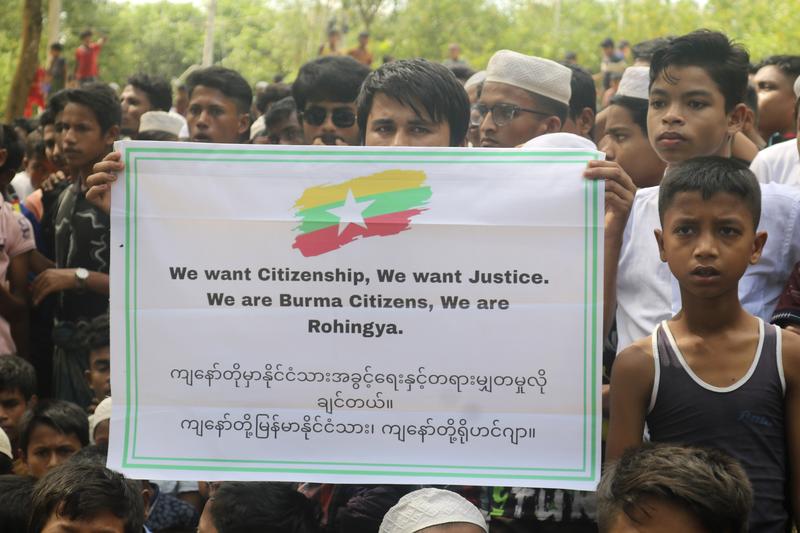

( Shafiqur Rahman / AP Photo )

[music]

Melissa Harris-Perry: I'm Melissa Harris-Perry, and you're listening to The Takeaway. Thanks for being here. Today, we start with the Rohingya people, an ethnic group who are suffering under a violently discriminatory regime in the Southeast Asian country of Myanmar, formerly known as Burma. The most Rohingya are Muslim, while Myanmar is nearly 90% Buddhist. Back in 2017, the Burmese military began a brutal series of attacks against the Rohingya people. In the past five years, this violence has forced more than 700,000 into refugee camps in neighboring Bangladesh, and has claimed the lives of thousands more.

For the first time, in March of this year, the US State Department officially recognized the atrocities committed against the Rohingya as a genocide. Doctors Without Borders recently released a series of interviews with Rohingya living in refugee camps. Hashim Ullah is living in a refugee camp in Bangladesh.

Hashim Ullah: [foreign language]

Melissa Harris-Perry: "We have escaped, but our heart is still there," he said. "Even if our heart wants, how can we go back?" The genocide, which began in 2017, was not the first act of military-backed violence against the Rohingya. The government enacted waves of violence in 2016. Before that, in 2012, and even before that, throughout the '70s, '80s and '90s. The government has also employed civic exclusion, treating the Rohingya as stateless, unauthorized immigrants from Bangladesh, and stripping them of basic rights under the law. A Rohingya refugee named Mohamed Hussein explained what that meant in an interview with Doctors Without Borders.

Mohamed Hussein: [foreign language]

Melissa Harris-Perry: "We're treated as pariahs. That gradual deprivation turned into persecution," he says. "The unjust treatment came to the point where we had to leave." To help us understand more of the history and the current conditions of this ongoing crisis, I spoke to two people who understand that deeply.

Shayna Bauchner: My name is Shayna Bauchner. I'm a researcher at Human Rights Watch.

Raïss Tinmaung: My name is Raïss Tinmaung. I'm the founder and board chair of Rohingya Human Rights Network.

Melissa Harris-Perry: In 1978, Raïss' parents fled Myanmar for Bangladesh, and that's where he was born. The government in Myanmar had launched what was called Operation Dragon King, and mass arrests and deadly violence drove some 200,000 Rohingya across the border. Raïss has lived much of his life in Canada, and says his family was fortunate to escape.

Raïss Tinmaung: My parents were one of the most luckiest Rohingya's out there, and so am I. They had to flee because the discriminatory laws and segregation was getting worse and worse back in northwestern Rakhine. They had to flee by boats, come to the other side into Bangladesh. Very luckily at that point in time, they were not stuffing people into refugee camps, which is what happens today. As soon as you arrive in Bangladesh, you are confined in a refugee camp and you're not leaving anywhere. My parents were able to integrate into the Bangladesh society, like a lot of refugees back in those days. That's how we were able to make it outside of Bangladesh someday, and then finally into Canada.

It was a very difficult move to leave everything, all of our family behind. We were not able to keep our own language for the longest time because we were afraid we will not be integrated to Bangladesh, we will not be integrated into Pakistan, other countries where we also had to live. We didn't get passports, we didn't get papers. It was a difficult time, but nothing compared to what people are enduring today.

Melissa Harris-Perry: What did your parents understand the trade-off to be, what was facing them if they stayed?

Raïss Tinmaung: Well, the trade-off is freedom. The very sense of being able to move where you want to move, being able to earn a living. Being able to send your kids to education, that is priceless, which is what you do not get in Myanmar. People who are for my ethnicity, that is. People who are marginalized or targeted by the military, who are targets of extermination precisely. They're specifically not allowed to have economic activity. They're not allowed to move from one place to another, obtain medical help or send their kids to school. All of that, which is just very fundamental human necessities, they had to trade that for the their lands, for their homelands. That was a difficult decision take, of course.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Shayna, this language we just heard from Raïss' of targeted for extermination. Can you tell us what happened in August of 2017 to mark that as the beginning for this genocide against the Rohingya people?

Shayna Bauchner: Five years ago in August 2017, the Myanmar military launched a sweeping campaign of atrocities against the Rohingya. We were in Bangladesh at the time talking with hundreds of refugees who were fleeing across the border, who described Myanmar soldiers massacring and raping their family members and torching entire towns. Ultimately, over 700,000 were forced to flee across the border to Bangladesh, where today nearly a million are still in this limbo, in refugee camps.

I think one thing that's critical is understanding that the atrocities that happened five years ago didn't happen in a vacuum. That violence didn't come out of nowhere. It was built on decades of segregation, persecution, and dehumanization that authorities had imposed against the Rohingya because they identified them as a threat to the Buddhist state of Myanmar.

Melissa Harris-Perry: What are the kinds of atrocities that we've witnessed against the Rohingya people?

Shayna Bauchner: During the atrocities of August 2017, and the weeks and months that followed, there was extreme brutality carried out by the Myanmar military against the Rohingya in northern Rakhine, who appeared in Rohingya villages to carry out systematic massacres. The attacks at the time were very much pre-planned. They were methodical. They were designed to expel the Rohingya from Myanmar.

At the same time, in the year since, there are still about 600,000 Rohingya remaining in Rakhine State, and they are facing a different form of violence. They are being held under a system of apartheid and persecution. They face extreme restrictions that are also designed to erode their capacity to survive just in a different way. They are dying from preventable diseases. Just yesterday, there were reports of Rohingya who died at sea while trying to flee the country. It is a different type of violence, but no less extreme.

Melissa Harris-Perry: As we're hearing from Shayna, this notion of a different type of violence, the invocation of an apartheid language, I'm reminded also here of the partition of India and Pakistan. Can you zero in a bit and help us to understand the ways that a colonial legacy in Myanmar is part of what's playing out here?

Raïss Tinmaung: The colonial legacy certainly has played a role. The division and the partition of India, or the formation of the different countries in Southeastern Asia, with land borders that were created haphazardly by Lord Mountbatten and all the players in that arena, it created catastrophes that are trickling down to today, and that will trickle down, hopefully not, but very likely for the next several decades. The Rohingya, who were very similar or spoke similar language to the remainder of eastern India population. However, when these borders were drawn, we became part of Myanmar, which we do not regret at all.

We have a lot in our history. We have a lot of resemblance and a lot of cultural assimilation with the Burmese. Even though the colonial legacy made this partition and separated us from mainland India, of course, just the way they separated Bangladesh, i.e. East Pakistan back in 1947. Even despite of that, the Burmese mainstream population recognized us as an ethnic minority. However, that acknowledgement did not get fully transmitted to the rest of the population.

As time progress, with divide and conquer and with politics, and with increasing right-wing Buddhist nationalism, this division widened further and there we are today. There we were in 2017, 2016, 2012. All the massacres of the early '90s and 1978, when my parents left. All these different massacres that took place, which is a consequence of all these divisions and haphazard boundary creations by colonial powers.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Shayna, I also want to give you an opportunity to weigh in on this history as we've heard it here from Raïss, and particularly in terms of this notion of the Rohingya operating as a threat to the right-wing Buddhist government.

Shayna Bauchner: Because of the Rohingya's ethnicity and because of their religion, the authorities identified them as this threat. Identified them as something to be designated as an other, as outsiders. That the military and successive authorities would gain more power from segregating and isolating the Rohingya. In 1982, they passed a law essentially nullifying the Rohingya's citizenship despite the fact that Rohingya had lived in Myanmar for generations and generations. Essentially, overnight, they became the largest stateless population in the world. Without that protection of citizenship, authorities were able to peel back all of the other rights that nationality is supposed to ensure.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Shayna, for those who do stay, who do remain, what are the options?

Shayna Bauchner: They are very limited. They face extreme restrictions on a daily basis. Restrictions on their ability to study, to work, to move freely. There's a junta in place, which is led by the same generals who carried out the 2017 atrocities against them. The situation has become even more dire. There are more movement restrictions, new checkpoints being set up, increasing punishments. The junta has arrested thousands of Rohingya just for what they consider unauthorized travel, basically, just for moving around the country.

The Rohingya refugees we talked to in Bangladesh, they want to go back to their homes in Rakhine State one day, but only when they can do so safely and freely. Those conditions just don't exist today, and they can't exist while Min Aung Hlaing is sitting in Naypyidaw.

Melissa Harris-Perry: One thing we know, Raïss, from the history of genocides is that it is not only the active engagement of those committing the atrocities, but also the willingness of so many others to ignore or look the other way. How have Burmese people who are not Rohingya responded to this?

Raïss Tinmaung: The people around us, the neighboring countries, they did not do anything, except for Bangladesh, which is generous enough to take us into the refugee camps. Otherwise, we would've all been massacred or drowned in that river. The neighboring, surrounding ASEAN states, with the exception of Malaysia perhaps, and Indonesia at times speaking a few words, they were all quiet. They called it internal affairs. Even today as we speak, ASEAN, which is the prime coalition of Southeast Asian states of the powers in that region, they are gradually accepting the military regime.

[music]

Melissa Harris-Perry: A quick break. Stick with us, we'll be continuing our conversation about the Rohingya. This is The Takeaway.

[music]

We're hearing about the ongoing genocide against the Rohingya people with human rights activist Raïss Tinmaung and Shayna Bauchner, a researcher with Human Rights Watch. For years, Myanmar's government has been leading a campaign of targeted attacks against the Rohingya people in what has now been recognized by the international community as a genocide.

Raïss Tinmaung: Few have stood up and said something. Canada has been among the first nations to call it a genocide. We contributed funding to support the incoming refugees, so did the UK and the US as well. A lot of nations did not formally recognize it as genocide, and hence there weren't any policies that were put in place to counter what was happening. The Biden administration just in March of this year, after five years of the last massacre, acknowledged it as genocide.

With the slowness of the response, you can see how the rest of the world is indifferent. It's too far from home, so it doesn't bother them. That is how the attitude has been. The perpetrators have a green signal to carry on what they want to do.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Shayna, in July, the UN International Court of Justice did allow a case against Myanmar to move forward around this issue of genocide. Has anything changed since July?

Shayna Bauchner: There have been governments who have announced that they will be supporting this case at the International Court of Justice, which, as you said, was approved to move forward in July. Myanmar had put forward preliminary objections to the case, which the court rejected and decided that Gambia, which had brought the case, does have jurisdiction to move ahead. Since then, Canada and Netherlands, which had previously announced they were planning to support the case, reconfirmed that decision, and we've also heard that the UK and Germany are also going to be intervening in the case and supporting The Gambia's effort.

There are, though, other avenues for justice and accountability, particularly the individual accountability, which can happen at the International Criminal Court, but which needs a UN Security Council referral to happen. One of these key pieces of inaction that Raïss describes has been the Security Council, which has done far too little over the past five years when it comes to seeking justice for the Rohingya. Instead, it's been stuck in inaction. There is concern that a Security Council resolution on Myanmar would be vetoed by China and Russia, but that doesn't mean that they shouldn't even try. They could put forward a resolution, referring the situation to the ICC, and make China and Russia go on the record defending this brutal military regime.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Raïss, what could bring this genocide to an end?

Raïss Tinmaung: As a first step, the Biden administration has the determination of genocide in March. As a first step, it's very welcome and it's a fantastic direction moving forward from a superpower. The United States can utilize a wide range of tools to implement pressure and tactics on Myanmar that would prevent it or deter it from going further, or bring it to listen to the voices of people and have a democratic government in place.

Starting from economic tools, for example, crown corporations in Myanmar, like Myanmar Oil and Gas Enterprise, its short form MOGE, utilizes US monetary systems to conduct its transactions, and they're still not sanctioned. A lot of the oil and gas that are state-owned and that are funneling the pockets of the military generals that are conducting the massacres and breakdowns of peaceful protests by civilians across the country. This is now going beyond the Rohingya to all the other ethnicities that are also being cracked down today. All of them are getting funded by these transactions that they're still making in the absence of sanctions.

Melissa Harris-Perry: I want to give you a chance to weigh in on this, Shayna, because of the level of distressing and complicated that is.

Shayna Bauchner: Certainly, the economic revenue that the junta is continuing to bring in that is underwriting the abuses it's carrying out on a daily basis now across the country is key to imposing consequences that, frankly, should've been imposed five years ago and weren't, but are even more urgent today. As Raïss mentioned, the oil and gas industry, which is the junta's largest source of foreign revenue, brings in $1 billion to $2 billion a year, could be targeted. The EU imposed sanctions on MOGE, the Myanmar Oil and Gas Enterprise, but other countries can follow suit. The US, in particular, given how many transactions happen in US dollars, would have significant impact on the revenue flow to the junta and potentially on its calculations.

In terms of avenues for justice, I think looking at the International Court of Justice's decision in July holds a really key piece and message for other governments who are looking at this situation. One of Myanmar's objections to the case was that Gambia didn't have standing to bring the case because it doesn't have direct ties to the Rohingya. In rejecting those objections, the court affirmed that there are abuses that are so grave, including what the military carried out in Myanmar, that every country in the world has a responsibility to protect the people who are facing them and to hold to account the people who are committing them. That is why Gambia stepped forward to bring the case out of this vision of shared humanity. I think the Rohingya, like so many other groups, are tired of hearing, "Never again," when more could have been done five years and could be done to actually keep these atrocities from happening again.

Melissa Harris-Perry As a final note, Raïss, because I never want to leave a people just in the space of being defined by the worst atrocities that have been enacted against them. Can you take us to a close here by telling me about what the contributions with the life, with the joy, what it means to be Rohingya? What is lost in this attempt to exterminate?

Raïss Tinmaung: As soon as you arrive at the refugee camps which you see around, you are children. There are children and children everywhere. You're looking at 500,000. About half the population of refugee camps are under 18. These kids will be all running around you and gathering around you as soon as you get off the rickshaw. I normally take the rickshaw. I go very local and very low-key.

I assume as the rickshaw arrives, you get off, you'll see kids jumping around you, and laughing and running. Some of them without clothes, some of them barefoot. Some of them just a little donated pair of pants that they wear. It's just surprising. It's just so enlivening that they are oblivious to everything. They're just living life with whatever they have, not knowing what will happen tomorrow. Infant mortalities is among the highest in the refugee camps, but they are just being kids.

There is hope. Human beings find hope, and God has given us hope. If we can at least nurture that hope, if we can at least save those children, I don't know if you're aware that the refugee camps in Bangladesh are perhaps amongst the only refugee camp out there that does not allow access to education to children. Education is barred, and so is economic activity. We are considered as transient people and we should not have the "luxury" of economic activity or education. Anyway, if the kids are to be at least provided education, if they're at least to be provided hope for the future, that is something that you cannot take away.

We are still a nation. We are still a people. We are still survivors. We're still breathing loving human beings who love our culture, our roots, our language, and we stand for it. We're not going to take the NRC cards, those cards that are given to us as the Jewish cards equivalent during the Holocaust. We're not going to take labels that you do not belong to us or you do not belong here. We belong there for generations and we are determined to go back. We are determined to contribute to Myanmar because we have already contributed and we are capable, intelligent, hardworking, and proud people, and that you can never take away from us.

Melissa Harris-Perry Raïss Tinmaung is the founder and board chair of Rohingya Human Rights Network and the Canada-based coordinator for the Free Rohingya Coalition. Thank you for being here, Raïss.

Raïss Tinmaung: Thank you so much, Melissa. Shayna Bauchner is a researcher at Human Rights Watch focused on Myanmar and Rohingya refugees. Again, thank you so much for being here, Shayna.

Shayna Bauchner: Thank you both so much.

[music]

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.