Robin Coste Lewis Talks with Hilton Als

[music]

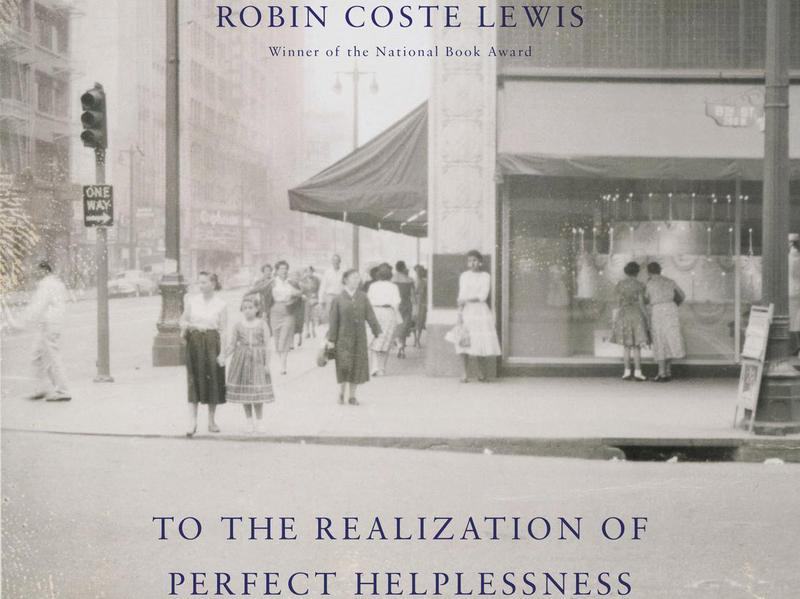

Speaker 1: Hilton Als is a longtime staff writer for the magazine and one of the best cultural critics working today. Recently, Hilton wrote about a new book called To the Realization of Perfect Helplessness. It's by the poet Robin Coste Lewis and it was inspired by a collection of family photographs. It's a book Hilton says about how the dead do not stay dead. Robin Coste Lewis joined Hilton Als on our program in 2016 after the release of her last poetry collection. Her debut, Voyage of the Sable Venus, won the National Book Award for poetry.

Hilton Als: Oh my God, this book is one of the high points of my life. I begged to review it.

Robin Coste Lewis: Thank you.

Hilton: I said, "She's going to win this award."

Robin: I'm glad everybody knew. I didn't know.

Speaker 1: Voyage of the Sable Venus took its name from an 18th-century engraving.

Robin Coste Lewis: There's a gorgeous Black woman on a clamshell-like Botticelli's Venus and she's attended by all these classical figures. It isn't until you really look at that, you realize it's a pro-slavery image because Triton or Neptune is carrying, instead of a Triton, he's carrying a flag of the Union Jack.

Speaker 1: That got her interested in images of Black women in western art, a research project that got much bigger than she ever anticipated.

Robin: It just spurred me on and it was like, well, wait a minute dam it. If this title is so complicated and so rich, what are other titles doing? It just led me on this whole path. I really thought at the time it was going to be a few pages long, and then every time I would do research, it would just get darker and deeper and longer and more horrid. It just didn't stop, it didn't let up. The Western Art Project, as beautiful as it is, it also has such a ugly underside for so many kinds of people.

Hilton: Well, it had to hack away at-

Robin: Absolutely. Absolutely.

Hilton: -other things in order to stand on something, right?

Robin: Right. For me, if I would go into a museum and see some kind of grand historical painting about some emperor doing something fabulous, conquering some land, there might not have been a Black woman in that painting, but the frame might have had Black female bodies carved throughout it in some subservient position. Do you know? We're not supposed to notice that frame and we're not supposed to think about it, but it's there.

That's what was so fascinating to me, is that there are so many Black women in exhibitions all over the world in every time period, in every country, every continent, it's everywhere, but you wouldn't think of it because who would think to look at the carving of a comb closely or the face of a button for an emperor? Why would someone need to carve a Black female body onto the button of an emperor? Why? Then when you start looking just for that, that's when it begins to emerge. I don't know that I would have seen that had my brain not slowed me down and made me look more slowly.

Hilton: I know that you began writing poetry because of something that happened. Would you mind talking about it?

Robin: Not at all. Not at all. I was in what they call a catastrophic accident. I fell through a open stairwell and I--

Hilton: What does that mean? There were no stairs.

Robin: There was no rail.

Hilton: There was no rail.

Robin: That I didn't know and it was a dark room. I was going to get my coat in a restaurant and they failed to tell me there was a hole in the middle of the floor and I walked into air.

Hilton: Where was this?

Robin: In San Francisco. I was at a conference and I was just having dinner with a friend and I got cold and I asked for my coat and they led me back to this room and said, "It's over there." I could see my coat hanging on a wall, but I couldn't see the hole on the floor.

Hilton: Oh, my gosh.

Robin: I fell through, and for the last, I guess it's 16 years now, 16 years I've been doing a lot of rehab and recovery and somewhere--

Hilton: What was the effect of the falling?

Robin: Oh, thank you. I was diagnosed with permanent mild to moderate brain damage, so a traumatic brain injury.

Hilton: Oh, my God.

Robin: Then I had all kinds of injuries all over my body. I still have so many surgeries to have that I'll be going into soon. The most devastating part of it was the brain injury. At some point, I couldn't read or write and I was very, they call it exquisite hypersensitivity. Everything triggered some kind of symptom. Talking, walking, seeing, hearing, smelling, you name it, anything that had to do with the senses would send me into a spiral where I would end up sleeping for days upon days. My memory, I fought really hard for a year to teach myself the alphabet again. It took a year just to do that because the language center of my brain was badly damaged.

I hate to be that person that is always looking for the green side of something, but it turned out to be, in many ways, a blessing in disguise, a brain damage, the gift that keeps on taking.

[laughter]

Robin: I joke with my friends that this book is actually about brain damage. I know I would not have written this book had I not had that accident partly because if I'm going to die, I can write whatever the hell I want.

Hilton: Exactly. You're free.

Robin: I'm so free and there's no one to care about much in terms of pleasing. Also, the doctors told me I can only write one line a day and I could only read one line a day. That, of course, spiraled me into an incredible depression for several months. Then at some point-- You know how that voice of grace just comes into your mind? This voice just said to me, "Okay, then. It's going to be the best damn line I can think of." Every single day I would spend in bed thinking of the best line. I couldn't write because my hands were all in different casts and all kinds of splints.

Hilton: Were you a mother when you had this accident?

Robin: No. No, no, no.

Hilton: No.

Robin: They also told me I couldn't have a kid. [chuckles] They told me I could never write again, teach again, read again, and not become a mother

Hilton: You've done all those things.

Robin: I've done all those things. [crosstalk] I was annoyed. I was enraged.

Hilton: There's nothing like being annoyed to get [crosstalk] the juices going.

Robin: Oh yes. Absolutely.

Hilton: Tell me about your son and how did that miracle occur to you?

Robin: Oh, my God. What do you mean how did--

Hilton: Well, I know how it happens.

[laughter]

Hilton: Well, the decisions and--

Robin: There's a bird and there's a bee.

Hilton: Yes, exactly.

[laughter]

Hilton: There's a stork and a dipper.

Robin: Exactly.

Hilton: How did you decide to become a mother?

Robin: This is such a great question. I have been haunted with being a mother all my life.

Hilton: Really?

Robin: Yes. I'm one of those crazy women who just always wanted to be a mother. When they told me I couldn't have kids, I really had to think about it and I thought about it for a decade. What does it mean to be a disabled woman and to have a child and don't be selfish and mess with this kid's life if you can't really raise him or her well? Then one day I was walking down the street in Boston. I was doing major rehabilitation at the time. I was in occupational therapy, speech-language therapy. Just going outside would hurt.

One day I'd gone to do something and there was a woman, this gorgeous woman in power wheelchair wheeling down the street at what felt like to me 60 miles per hour with two of her kids in her lap.

Hilton: Wow.

Robin: She was high talented. They were having such a good time. I was like, "You idiot. If this woman can raise her kids, you can have a kid. She was such my inspiration. Then I was hellbent and I tried and tried and tried for many, many years and then it finally happened, finally happened. The deep irony for me is that my father was the first person to tell me way before my accident, "I think you really should have a Baby Robin. You want to be a mother. You should just do it." My father was incredible. He was funny too.

Hilton: I love him already.

Robin: Oh, he was so good. The deep irony is I found out, after years of trying to get pregnant, I found out I was pregnant four days after my father's funeral-

Hilton: Oh, wow.

Robin: -which felt so magical to me because I always told him, "When you die, you better take me with you because there's no reason I'm staying without you." When I found out I was pregnant, it felt like he stayed with me in some way.

Hilton: How does the accident impact you today?

Robin: Well, I've grown comfortable with being brain-damaged. It's become familiar. You know that saying that human beings can get used to anything?

Hilton: Yes.

Robin: I got used to it.

Hilton: You work around it.

Robin: I work around it. I've learned how to take care of myself. I was just at a party on Friday in Miami at the BookFest and I was starting to get symptomatic and I was like, "You should just go. You have a reading tomorrow, and if you don't go and go to sleep, by the morning your face will be numb. Your left arm will be numb. You won't be able to remember how to spell your name or even where you are so just go to bed." In those ways, but then also in lovely ways. I don't know, I still very much appreciate that my brain has become a odd little bad fellow with me. We love each other. I'm like, "You're a freak brain," and that's sexy to me.

I like that you see these things that other people aren't seeing, but keep it to yourself and we'll try to turn it into art at some point.

Hilton: Yes. It changes your perspective profoundly.

Robin: Absolutely and I--

Hilton: Does it help you parent in a different way do you think?

Robin: Absolutely. It helps me put it in fifth gear every day from the gate. I'm--

Hilton: As you wake up with him and it's like, "Look, we're here."

Robin: Absolutely. Also, this is the [unintelligible 00:10:23] part, supposedly, my brain won't last as long as most people's brains will last. I know that and I think that's also why I push myself so hard to write. Then there's a certain urgency I feel like I'm fighting the clock until my brain starts to rot. I try to have a lot of fun. I try to parent him for the future. I've already-- I have a whole library for him once I'm gone. I have friends sign books to him for the future because I know there's going to come a time where I won't be able to be present in the same way that I am now. I just--

Hilton: Do you talk to him about that?

Robin: I do. I had to because I guess my disability is invisible. The way I described it to him when he was younger, I said, "It's like mommy's brain is in a wheelchair." Sometimes, it's hard because he's a gregarious, precocious, fabulous child.

Hilton: He's about eight now.

Robin: He's seven and I have to tell him sometimes to be quiet, that's a drag. That's just a drag or I can't-- I'm sad that he doesn't know the person before my accident because I was a huge audio file, music collection that's brilliant. I can't listen to music and have people talking at the same time in a room unless it's a lot of people talking. Things like that, I'm constantly [unintelligible 00:11:45] I'm constantly repressing his little spirit in ways [crosstalk] in order to stay asymptomatic and take care of him or make dinner. In those ways, but it's also okay because I feel like he's getting to learn about the ways in which bodies are different.

Hilton: Those are the ways in which life curtails us.

Robin: Absolutely.

[music]

Speaker 1: Poet Robin Coste Lewis. She spoke with the New Yorker's Hilton Als in 2016. Her new book is To the Realization of Perfect Helplessness.

[music]

[00:12:29] [END OF AUDIO]

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.