Richard Brody Makes the Case for Keeping Your DVDs

[music]

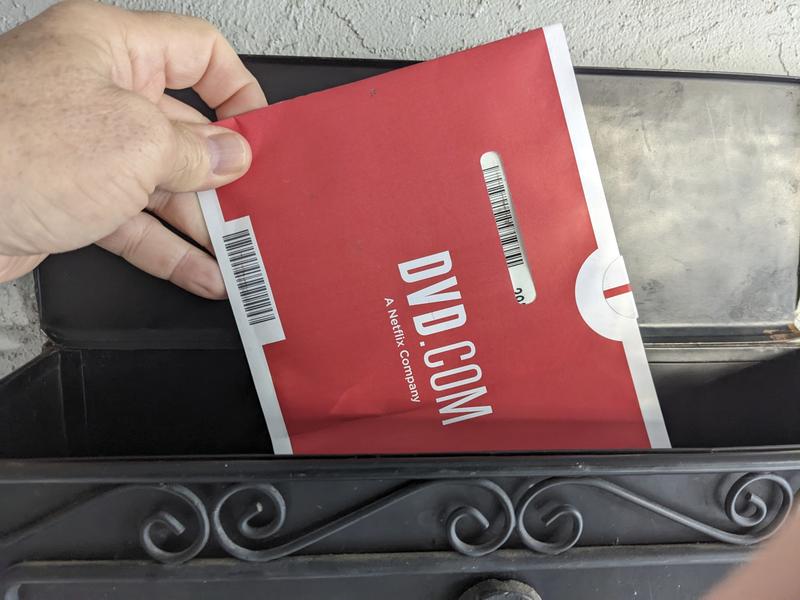

David Remnick: At the end of this month, after more than two decades, Netflix is phasing out its DVD rental business. Yes, its DVD business. For a casual movie fan, this seems like just an inevitable step toward the ubiquity of streaming, but keep this in mind. Streamers like HBO Max and Disney+ drop titles from their platforms by the dozen all the time, and they don't give you a lot of explanation or warning, and so, for real movie fans, that's not good, and they're taking the Netflix news hard.

Speaker 1: Hi. How can we help you, sir?

Adam Howard: Hi, we're here for Richard Brody.

Speaker 1: Okay, one second. Our producer, Adam Howard, went the other day to commiserate with The New Yorker's Richard Brody.

Adam Howard: Hey, Richard.

Richard Brody: Hey, hi.

Adam Howard: Thank you so much for letting us invade your home.

Richard Brody: Nice to meet you.

Adam Howard: I really appreciate it.

Richard Brody: Oh, please. Come on in. Welcome. Well, you are welcome.

Adam Howard: [laughs] Thank you.

Richard Brody: It's good to see you.

Adam Howard: Good to see you.

David Remnick: Richard Brody writes our column, The Front Row. As an obsessive cinephile, his apartment and his desk at work, I can attest, are stacked to the ceiling with DVDs.

Adam Howard: As I'm sure you know, Netflix has decided to discontinue their disc rental service. I think for a lot of people, this news might be greeted with a shrug, but I imagine for someone like yourself, who's a film critic and a film enthusiast, you might greet this news with a little bit more concern.

Richard Brody: Well, Netflix's discontinuation of their DVD rentals is indicative of the overall demise of physical media. Physical media is what protects us from being at the complete mercy of streaming services for our movies and our music. It's like having a library at home.

Adam Howard: When it comes to physical media, is there an ideal format? Some folks back in the day used to have laser discs.

Richard Brody: I was pretty excited when VHS came in because it didn't just mean rentals. In fact, VHS were hardly ever meant for purchase, except for the wonderful knockoffs you'd find at convenience stores. That's how the first VHS I ever bought was Orson Welles's The Trial.

Adam Howard: Oh, wow.

Richard Brody: A complete and total bootleg. It cost me $2, and the film wasn't really available in other forms.

Adam Howard: Where would you have found Orson Welles's The Trial?

Richard Brody: Duane Reade, CVS.

Adam Howard: That was at a Duane Reade?

Richard Brody: Yes.

Adam Howard: [laughs] You think it's fair to say that getting a DVD player or a VHS player is still a worthwhile investment?

Richard Brody: Well, VHS, I don't know. Depends on what you've got. I mean, I had hundreds, maybe thousands of VHS tapes, most of which I had recorded off TV, but I got rid of them over time. The ones that I needed, I would simply copy from VHS to DVD, and then I gave them away or threw them out, depending, but DVD player? Absolutely, because that format, I think, is going to be around for quite a while.

Blu-ray, I don't know. I mean, Blu-ray has something almost hyper realistic about it. Sometimes when I watch a Blu-ray, I feel like I'm seeing things that would never have been seen had I been watching a movie in a theater. It's like watching a microscopic view of a movie.

Adam Howard: It's definitely making a lot of toupees much more evident, which is unfortunate for a lot of people. One of the things I sort of miss is, when I was a kid, just going to the video store and just looking at the boxes and taking a chance on something that looked cool. I'm curious how much you think has been lost from that transition from the experience of walking into a store and renting a movie or buying a movie, talking about it with your friends, to just sitting at home and scrolling.

Richard Brody: Well, it's funny how the idea of the communal has regressed. When home video came in and people started renting movies and watching them at home, a lot of people lamented the fact that the communal experience of theaters were being lost in favor of people sitting alone or privately and watching movies at home.

The first DVD I ever bought was also a convenience store knockoff. It was of the musical The Pajama Game, probably for $2. The beauty of it was that this was a print that was put onto a DVD with no restoration. I felt like I was sitting at the old repertory house Theatre 80 on St. Marks Place, watching a beautiful yet beat-up old print.

[MUSIC: Pajama Game: Small Talk]

Babe: I've got to buy me a dressy dress

The one that I have is such a mess.

Sid: Small talk.

Babe: Who would you vote for next elections?

How do you like the stamp collection?

Sid: Small talk.

Read in a book the other day

That halibut spawn in early May

And horses whinny and donkeys bray

And furthermore

The Pygmy tribes in Africa

May have a war.

Adam Howard: Yes, you mentioned some of your own collections. We wanted to talk about what your most precious items are. Theoretically, if there was a horrific fire and you had an opportunity to save films from your apartment, what films those would be and why?

Richard Brody: The first is a homemade. It's Godard's King Lear, which I consider the greatest film ever made, literally. I think it made about $0.33 when it was released. I mean, I saw it three times the week it opened, and I think I multiplied its box office significantly. It's a great movie. It has Molly Ringwald. It has Burgess Meredith. It has Peter Sellers, the theater director, playing William Shakespeare Jr. the Fifth. It has Norman Mailer. It has Woody Allen.

Adam Howard: It's an insane cast.

Richard Brody: It's a great movie.

[MUSIC: King Lear: Soundtrack]

Actor: What do you think will happen now?

Actress: Before seven years have passed, the Americans will lose everything they have in France in a great victory, which God is sending to the French. I say this now so that when the time has come, it will be remembered that I have said it.

Richard Brody: It not only did not do well, but it got terrible reviews. It's sort of a film monde, a film that its greatness is in diametrical disproportion to the reviews that it got at the time, which is not available on DVD.

Adam Howard: Really? Not in any format?

Richard Brody: Not in any format.

Adam Howard: Okay, so how did you get it?

Richard Brody: I got it because it was broadcast on this channel that was called Uptown, and I recorded it on VHS. Then when I feared that the VHS tape was going to get old, I transferred it to DVD.

Adam Howard: Let's see what's next.

Richard Brody: Well, one of the most important things about home video is that it makes available movies that are rarely available in any other form. One of them is Chameleon Street, Wendell B. Harris, Jr.'s 1989 movie.

Adam Howard: Amazing movie.

Richard Brody: It's a very loose adaptation of the real-life story of a man named Douglas Street who was a famous impostor. He was a Black man in Detroit who had enormous intellectual ambitions, was stuck working in his father's small business, and made his escape by way of pretending to be a lawyer, a doctor, a student. He even performed surgery successfully before he was caught.

Wendell B. Harris: I'm so far ahead of you. I know what you're about to say. I know what you're thinking. I know what you're writing on those evaluation papers. I know that you're wearing an incredibly cheap toupee. I could sit here and punch all the right buttons and make you think you're a genius, correctly analyzing this complex, exotic, notorious Negro, but-- Notorious Negro. That'd be a good name for my autobiography.

Adam Howard: I actually was introduced to this movie in college because of a VHS tape, because some friends of mine randomly bought it. I think they thought the box looked cool. They watched the movie and then they were like, "You should see this movie because this main character reminds me of you." They said, "This character reminds me of you," which is always a weird thing to hear. Then when I saw the movie I was like, "Well, this character is very cool, so I'm excited about that."

Richard Brody: I both love the movie and love the fact that it's available to me at my disposal on DVD any time I want. Also, I should add that I had the honor of having this DVD inscribed to me by Wendell B. Harris himself.

Adam Howard: Yes, that's an amazing choice. I'm very excited about that one. Okay, let's take a look at this next one.

Richard Brody: This is a set that came out very recently of another pair of American independent films. The two films are called Stranded from 1965 and The Plastic Dome of Norma Jean from 1966, which is also, by the way, the first film that Sam Waterston appeared in. The director is Juleen Compton. Stranded is one of the great American independent films. I think that if I had seen it in a timely way, if I had seen it in my youth, it would have changed my life. For the better, I should add.

Adam Howard: Why do you say that?

Richard Brody: It's a movie that shows what an American filmmaker can do with a particular European artistic sensibility in mind. It's essentially an American new wave film, an American and French new wave film, with Compton herself playing the lead role as an American woman in Europe, going from one adventure to another, very free-spiritedly.

Adam Howard: Can I see what the full collection is called, the title? Cinematic Journeys: Two Films by Juleen Compton. Yes, I've never heard of her.

Richard Brody: Her work is virtually unknown, and this only just came out. It's a fact that should change the future course of film history, that people can readily see her films.

Adam Howard: Wow, that's a lot of enthusiasm, so that makes me want to check it out. What else have we got?

Richard Brody: I'm a John Cassavetes freak.

Adam Howard: Sure. I mean, I like him, too.

Richard Brody: Cassavetes is, in effect, the quintessential American independent filmmaker, someone who already made a career as an actor in Hollywood, but knew that he wanted to direct and did so in unusual ways. His first feature, Shadows, was done with the 1950s equivalent of Kickstarter. He went on the radio and solicited funds. People would

subscribe to the movies for $5.

Adam Howard: That's crazy.

Richard Brody: He would use the money that came in to make the film. Then because of their investment, they would have a ticket to see the movie. Cassavetes is a very personal director. Most of his great movies were made with his wife, Gena Rowlands, who is, in my opinion, the greatest living American film actor. Very personal films about domestic life, about family life, about the frustrated passions of American middle-class men. For the longest time, his films were very hard to see.

Criterion put out a box maybe 10, 15 years ago of five films, Shadows, Faces, A Woman Under the Influence, The Killing of a Chinese Bookie, and one that was among the rarest, Opening Night, that never got a proper release. He released it himself. When it was released, it was not reviewed by any major publication, including The New Yorker.

That is the profoundest film about the life of an actor, about the work of an actor, that I've ever seen. It culminates in a spectacular sequence in which Cassavetes and Rowlands are on stage together doing a play that she doesn't want to do and that she transforms improvisationally into a kind of psychodrama in real time.

Gena Rowlands: When were you ever funny?

John Cassavetes: When was I ever funny?

Gena Rowlands: I never heard you tell one stinking joke and you never laugh at anyone else, never.

John Cassavetes: I used to be funny. I used to be very funny.

Gena Rowlands: When?

John Cassavetes: When I was a kid. [laughter]

Adam Howard: Yes. That's a very intense movie, in a good way.

Richard Brody: The possibility that these films should be unavailable seizes me with terror. I would take these with me in a fire.

Adam Howard: This is a very random overshare, but true story. That box, that was on my wedding registry, because we had an unconventional wedding registry, because we had more than enough pots and pans when we got married. We put things on it like this, and so this John Cassavetes box set was purchased for my wedding, so we have that at home.

Cool, this is an amazing collection. I really appreciate you giving us a little window into your world and sharing this sort of private stash with me.

Richard Brody: Oh, it's my pleasure.

David Remnick: The New Yorker's Richard Brody, speaking with producer Adam Howard. Netflix's DVD service officially ends on September 29th. The company says that subscribers can keep their final batch of discs. In fact, they probably insist on it.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.