Brooke Gladstone: It looks like a pretty bleak winter ahead with COVID cases and deaths spiking around the country. Back in early February, as the virus was raging in China and Italy and elsewhere, but not here yet, we were still grappling with what was to come. We asked science writer, Laurie Garrettt, about an old advisory from our Breaking News Consumer Handbook: Infectious Disease Edition, the one that read, "Hollywood is pretend. Hollywood is pretend."

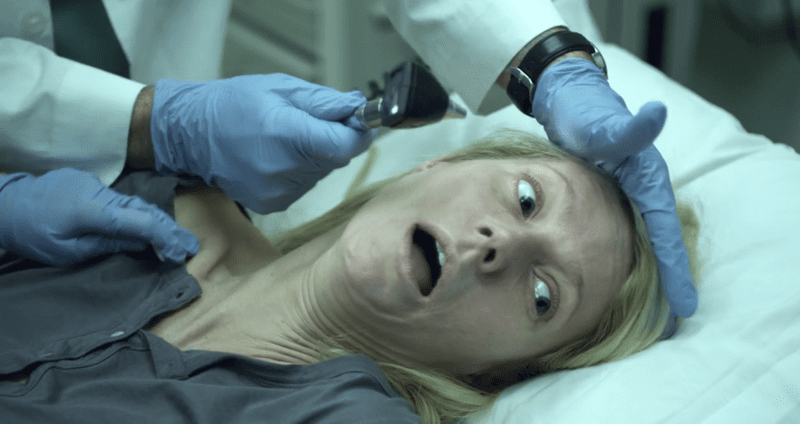

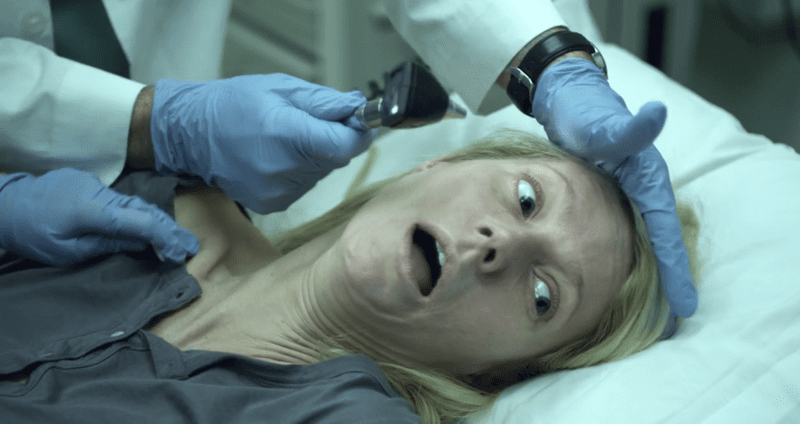

Laurie Garrett: I was one of the three scientific advisors on the film Contagion.

Dr. Erin Meads: Is there anyone else who might have had contact with her?

AIMM Employee 4: This was everyone.

AIMM Employee 2: Aaron Barnes did.

AIMM Employee 4: Barnes, he worked on another floor?

AIMM Employee 2: There were documents she needed to sign. He picked her up from the airport.

Dr. Erin Meads: He picked her up from the airport?

AIMM Employee 2: Yes.

Dr. Erin Meads: Where is he?

Laurie: We went to great lengths to make it as accurate as we possibly could.

Dr. Erin Mears: How are you feeling today?

Aaron Barnes: Pretty cruddy to be honest. My head is pounding. I probably got some sort of bug.

Dr. Erin Mears: Where are you right now?

Aaron Barnes: On the bus, heading to work.

Dr. Erin Mears: I’d like you to get off immediately.

Aaron Barnes: Wait, what? What’s going on?

Dr. Erin Mears: Where?

Laurie: Many of the things that you see in the background in Contagion are things that I've either personally seen happen or that we role-play. The empty shelves in the stores-

Customer: Is anyone even working here?

Laurie: -the robberies of pharmacies, people at gunpoint trying to get food, the breakdown of trucking, shipping, delivery. The "you're on your own, hunker down inside your home".

Wesley Morris: I heard that and I thought, "Well, if this person worked on that movie, I want to go back and watch it again and see how it feels to watch it now."

Brooke: That’s New York Times critic Wesley Morris. When we spoke to him in March, he told us that after hearing our segment, he downloaded the film for a re-watch that was at least initially comforting.

Wesley: It's just amazing how the letters for the organizations and the players in the crisis in nightmare that we're living now are in this neat little dramatic thriller that came out in 2011.

Brooke: I know. It's crazy. Down to the bats.

Dr. Hextall: The virus contains both bat and pig sequences. In the bottom right, you can see the dark green is pig and the light green is bat.

Wesley: One of the things I love about this movie is it's so much about competency, the belief that knowledge is the key to the solution to problems. Now in the real world, we also know that it's true, but we're at a moment where we don't know what to believe, and we don't know what to do in part, because we are in the middle of incredible incompetency for no reason. This movie isn't really about the panic. It is about professional people getting their brains together to try to figure out a solution to a thing that is obviously panic-inducing.

Brooke: As I talked to you, it strikes me that maybe this is a kind of public health West Wing.

Wesley: Yes.

Agent: Mr. President, I need you to don a mask. This is a crush. Put these on, please.

Bartlet: Is this a drill?

Agent: No, sir. The environmental hazard monitors detecting an unusual pattern of airborne particles.

Brooke: An idealized view of how it's supposed to work.

Wesley: It's even smarter to think about it that way, because that way you don't have to deal with Aaron Sorkin having written it. There's no romantic speech, and yet it is this romance of efficiency and of government as the solution to national problems. Watching all these women being in the basis and minds of the solution to this problem too, is also really fascinating.

Brooke: You said that watching movies stars being world savingly smart, really does lower your blood pressure, but the title of your piece is For me, re-watching Contagion was fun until it wasn't. When wasn't it fun?

Wesley: Halfway through the movie, watching Elliot Gould lose it in that restaurant, watching the glasses being cleaned, and the people coughing, but near the water. There was just something about the everyday-ness of a thing that a professional scientist might appreciate. Then I think I'd gotten a text from a friend of mine who was saying that another person had died. I just thought about the way that art can crystallize your confusion and answer your questions without really being the solution to a problem.

I felt in that moment that I was watching no longer, like a very entertaining worst case scenario, but a crystallization of a thing that is happening all over the world right now, which is that people are living their lives and people are dying. I know that that's the thing that happens every day. But under these circumstances, when we really ought to be thinking more about how we should be living our everyday lives, because people are dying, it got heavy for me.

Brooke: I was glad-- We could argue whether it could have been handled better, but I was glad that at least the issue of class and nationality was addressed. When the village outside of Hong Kong was really set to be extinguished because they would be at the bottom of the list that they decided to take a desperate measure.

Dr. Leonora Orantes: What's going on? Sun Feng, what's going on? Where are you going?

Sun Feng: You stay here with us until they find a cure.

Dr. Leonora Orantes: How is that going to help?

Sun Feng: You're going to get us the front of the line.

Wesley: It becomes clear that they are your usual Asian bad guys. They do tell a party line in terms of their skepticism about the seriousness of the virus, but then there's a plot twist. The plot twist to me is entirely moral. It winked at it, because the movie isn't about this class discrepancy, but it's not really about any one particular problem at all. It's about the number of ways in which a pandemic can bring out problems that already exist in societies.

Brooke: Unscrupulous journalists, the fundamental problem of supply, the ever-present concern of both under-reaction and military overreaction. It was a regular steaming bucket. You set this movie against 28 Days, the zombie film and the incredible novel Station Eleven, the AIDS documentary, How to Survive a Plague. I notice you don't mention the old Dustin Hoffman flick with the great chimp beginning.

Wesley: Outbreak.

Brooke: I'm just wondering in the Pantheon of bio apocalyptic films that you've seen, you thought it had what, the most gravity?

Wesley: I think it's the one that most directly overlays onto the moment.

Dave: My wife makes me take off my clothes in the garage. Then she leaves out a bucket of warm water and some soap. Then she douses everything in hand sanitizer after I leave. She's overreacting, right?

Dr. Erin Mears: Not really, and stop touching your face, Dave.

Wesley: It’s the most ideal movie of this sort to watch at this particular moment. This isn't pandemic porn, it is something much more considered in terms of this system having to work completely, all the agencies having to work with each other, maintaining, and I think this is really important, maintaining a tone among the agencies that keeps people from freaking completely out. The best of this style of movie is something like Invasion of the Body Snatchers, the one from 78.

Matthew: What is this supposed to do?

Kibner: Just a mild sedative to help you sleep.

Elizabeth: I hate you.

Kibner: We don't hate you. There's no need for hate now or love.

Matthew: There are people who will fight you, David.

Elizabeth: They'll stop you.

Kibner: In an hour, you won't want them to.

Wesley: I like myself, a really good allegory, but we don't have the luxury at the moment if we want to get the sense of how bad this can go, of being too existential, because I think we're still in the phase of procedure. We want a procedural explanation for what ought to happen. This movie is entirely procedural. There's not an existential question really in it. I truly honestly believe that there is something about watching people do their jobs well, people who don't get paid a lot of money to do those jobs, who are doing their work because they believe in it, and because it's the right thing to do, and because there are lives on the line and if you mess up, people will die.

It's your responsibility to get your stuff together, to help solve these problems. We are in a moment right now where that is not happening. Part of the reason people are going to keep dying is because the system isn't working the way it's supposed to. People whose job it is to keep us safe and to give us answers, they, at the very least, aren't giving us the answers, and the tools that are meant to keep us safe and tell us how much in danger we are don't seem to be working quite right.

You turn to a movie like this and you see not just so much how it could be because this isn't even a moral movie, it's entirely ethical, but it becomes moral when you watch it feeling that there's a lack of competence happening on the other side of the screen. I'll just say one other thing, which is that-- We should go back to 2011 for a second because when the movie came out, it just was another thing to go see on Friday night, and you can't go to the movies right now.

Brooke: [chuckles] Right.

Wesley: I wonder how we come out on the other side of this.

[music]

Brooke: Wesley Morris is critic-at-large for The New York Times as well as co-host with Jenna Wortham of The Time's podcast Still Processing. We spoke to him in March. Join us on Friday for the big show, and in the meantime, why not head on over to the donate button on our webpage onthemedia.org. For a small monthly donation, you can get your very own On the Media branded mask. Me of 8 months ago couldn't have imagined a world in which I'd be hocking face masks, but here we are. What a world. I'm Brooke Gladstone.

[music]

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.