BROOKE: Lenny Bernstein covers health for the Washington Post. After a 12-day reporting trip to Liberia in September, he wrote about the experience in a piece called “Reporting on Ebola: First rule is you don’t touch anyone.” Lenny, welcome to the show.

BERNSTEIN: Thank you I'm glad to be here.

BROOKE: We're talking early in the week. There's still watching to see if you're going to exhibit some symptoms.

BERNSTEIN: The virus can incubate for 21 days and I've been home 11. The last possible day I could have picked up ebola was Sept. 25 in Liberia. So as a precaution, I'm avoiding crowds. I haven't been back to the office. I'm staying away from my wife and daughter. It's just an abundance of caution, I have no symptoms and you can't hurt anyway when you don't have symptoms. You're not infectious.

BROOKE: Take me back to your decision to go to Liberia.

BERNSTEIN: I write a health blog for the Post. And we were following it, doing a lot of stories. And then a fellow on our staff went to Sierra Leone and reported from there. He's the first guy - very courageous guy - who went in. And then it became very clear that the story was moving to Liberia because the number of infections and deaths in Liberia was starting to outstrip the other two country. Sierre Leone and Guinea. And so I volunteered.

BROOKE: I guess there was a lot of competition for that Post.

BERNSTEIN: (Laughs) I don't know if there was a lot, but we were between Africa correspondents so they needed somebody.

BROOKE: Tell me about the reaction from your colleagues, your friends, your family....

BERNSTEIN: Pretty much everybody here in the United States thought I was crazy. My parents were very upset. My friends were very upset. My wife of course have veto power over this. And she concerned but said 'yeah, I understand the pros and cons you should go.'

BROOKE: The advice you received from other journalists was quite different and and pretty consistent. They said 'follow a few rules and you'll be fine.'

BERNSTEIN: 'Don't touch people. Try not to touch your face. Make sure you have chlorine on you at all times to wash your hands and wash your shoes. Be careful where you go when you're near the sick in case they sneeze or they cough. Or worst of all if they vomit. And you're going to be fine.'

BROOKE: But when you were in treatment centers you couldn't touch anything not even a wall, not a desk, not a piece of paper.

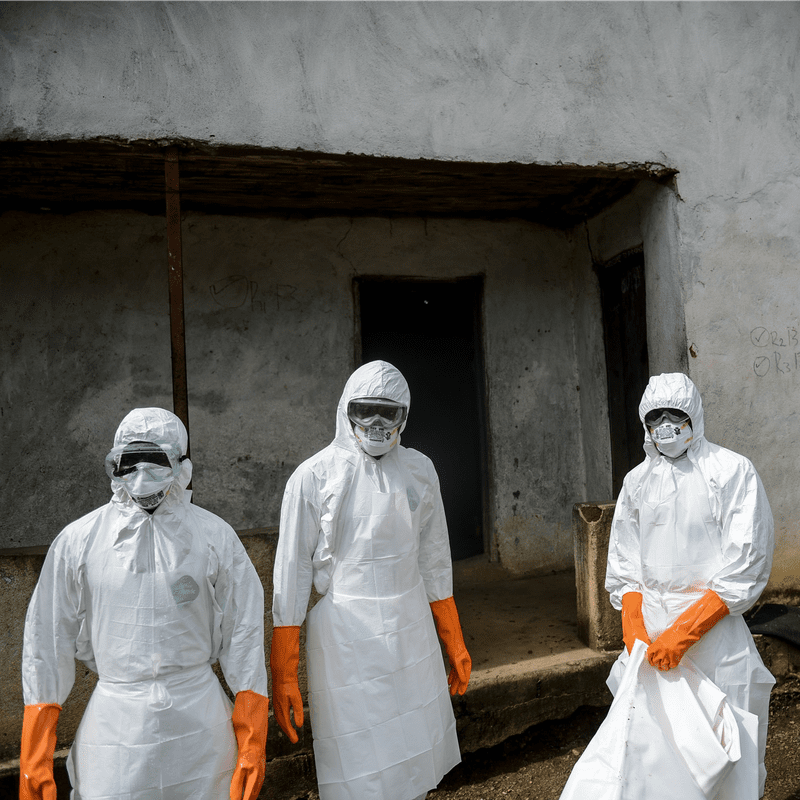

BERNSTEIN: That's if you went inside a facility where you didn't know whether their were sick people or not. So the major treatment center run by Doctors Without Borders, they have fencing there that keeps you away from the sick and you're ok. Once I touched a trashcan, and they said 'wash your hands' but you know, you were fine. But then another time I went into a small, private hospital. It was pretty horrific. Dark and shabby. Nothing that you would call a hospital here in the US. And I didn't know who was in there. I didn't know whether there were ebola patients there or they were just general medical patients there. I didn't know whether there was vaporized blood or other body fluids anywhere near me or on the walls that could harbor the virus even for an hour or two. So best rule there...don't touch anything.

BROOKE: Even if you're in the cleanest facility in the world if the virus gets on a piece of paper or on a piece of cloth and if the temperature is right it can live for days.

BERNSTEIN: Yes. The research on this is all over the map. Under ideal conditions they have recovered virus from surfaces after I think three weeks. I'll tell you a story, when we were sitting in the office of Dr. Jerry Brown - he runs ELWA2 - the treatment center run by Liberians - someone came in and handed him two slips of paper to ask his opinion on a patient who was out there and he looked at what was written down, handed it back and immediately washed his hands. You know it's just really a good precaution to take. Just don't touch. And if you do touch, wash your hands.

BROOKE: And that precaution, you didn't anticipate, would be so difficult. You wrote: 'I was goofing around with a small group of young children outside their home on a muddy, cratered road in the New Kru Town slum here. I made a scary face and the kids skittered, giggling...finally the boldest of the lot, a little girl perhaps five years old approached and stuck out her hand. 'Shake' she offered excitedly. 'No touching, I responded' keeping my hands at my sides. No touching.'

BERNSTEIN: IT's really sad, you know? If you walk down the street and there's a bunch of little kids there and you start playing with them, you're going to touch their head. Or shake if the kid wants to shake. You can't do that over there. You can't touch anybody. And it's very weird. Now, that's us Westerners. The Liberians unfortunately don't have that luxury because while they're odds are still good, we're only talking about thousands of infections among a population of 4.1 million people, they still are putting themselves at risk everyday.

BROOKE: You wrote that they play a daily game of Russian Roulette with their very lives, they press tightly together front-to-back in bus stop lines. They jostle at food distribution sites, they handle their own dead.

BERNSTEIN: They have no choice. They live in very crowded conditions in the city. Tiny little shanties with a lot of people squeezed in there. If one of those people has the infection imagine trying to not touch that person who lives perhaps in the same room as you do.

BROOKE: From your experience reporting there, how would you assess the press coverage here?

BERNSTEIN: I think the coverage has really brought home what is going on. Social media bothers me. The comments on stories are just crazy. You see a lot of racist stuff from people. And then one of the things that really bothered me was a Donald Trump tweet, that said 'We shouldn't let Kent Brantley back into the United States, he might bring the virus here.' Kent Brantley was a physician and a missionary in Africa caring for sick Liberians and he came down with the virus and they were racing him back here he was very close to death. To say that we should not bring this fellow back into the United States` and try to save his life when he was going to be in isolation the entire time. That's just crazy. There's a lot of scared people out there. And they need to tune in to what the actual risk is and how that risk is being managed.

BROOKE: Would you go back?

BERNSTEIN: Would I go back to Liberia. Like, today.

BROOKE: Yeah?

BERNSTEIN: Absolutely. It was a life-altering experience for me. I think the risk continues to be small. And it's a story that's got to be told until this gets under control. I'd go back there tonight.

BROOKE: Lenny, thank you very much.

BERNSTEIN: My pleasure.

BROOKE: Lenny Bernstein is a health reporter at the Washington Post.