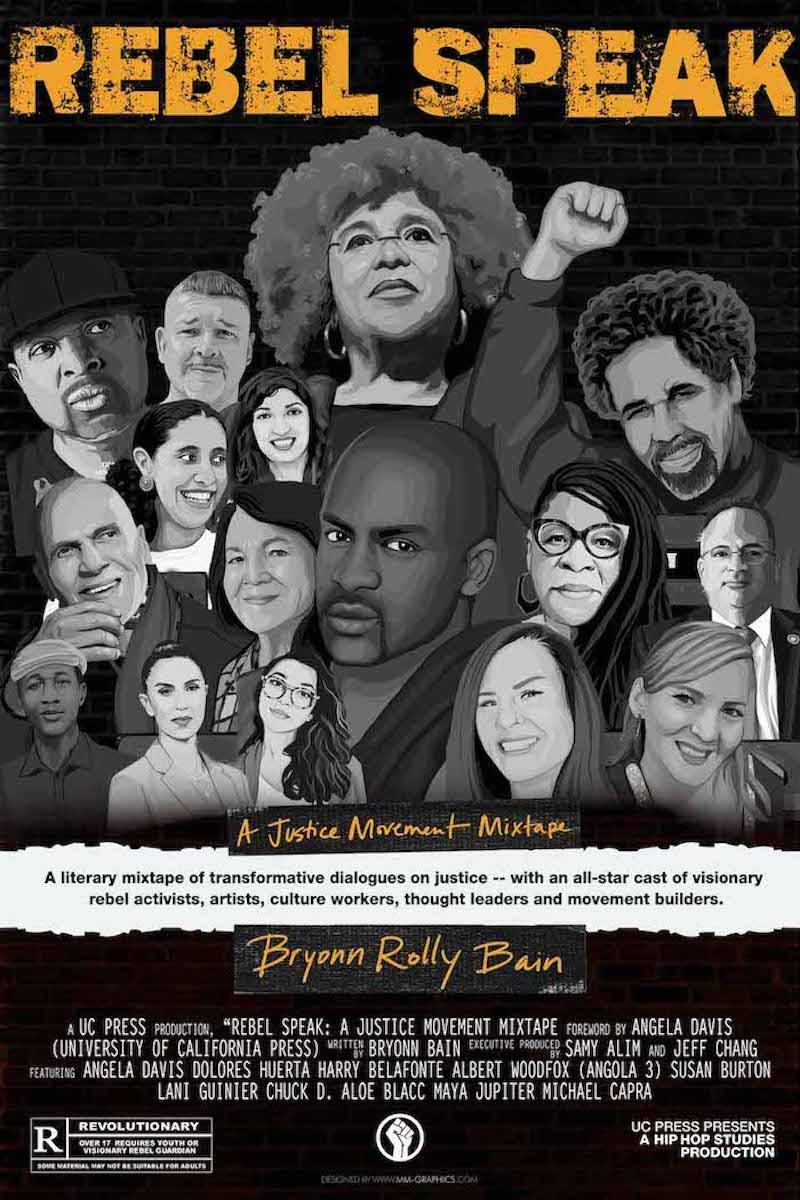

Rebel Speak: A Justice Movement Mixtape

( Bryonn Rolly Bain )

[music]

Melissa: Now, back in my day, the mixtape was the ultimate marker of love or friendship, a personalized soundtrack for relationships that mattered. You knew somebody was your person when they made you a mixtape. In the age of playlists and podcasts, they've been largely forgotten. Lots of team Takeaway has never made a mixtape. Scholar and activist Bryonn Bain remembers the format well.

Bain: The mixtape back in the '80s and '90s, you put together the music, the recordings you love for the people you love.

[music]

Melissa: Bain's new book, Rebel Speak: A Justice Movement Mixtape, replicates the intimacy of mixtapes but with a twist.

Bain: It's a recording of my conversations, interviews, dialogues, and essays with folks I love and have learned most from about justice and some of the leading justice visionaries in the country and in the world. It's my opportunity to give that to the folks I love, for my love of people to be expressed in this mixtape.

Melissa: Now, Bain's mix is comprised of thought-provoking essays and interviews with some very notable trailblazers, such as civil rights activist and singer Harry Belafonte, labor leader Dolores Huerta and legal scholar Lani Guinier, all of whom challenged and reinvented the way we view justice. Bain also sheds light on lesser-known stories of injustice through conversations with everyday people who aren't always given a visible platform.

Bain: Folks who are system-impacted, folks who are formerly incarcerated, folks who are often closest to the problems, are often closest to the solutions. That is really the spirit of the book, is bringing those folks to the center rather than from the margins where we're so often relegated.

[music]

Melissa: For the next installment in our week-long look at the books that have excited The Takeaway this summer, I wanted to focus in on this unique look at art and activism. Instead of chapters, the book is divided into tracks. When I spoke with Bain, I asked him to walk me through the major takeaways from some of those tracks.

Bain: Dolores Huerta and Harry Belafonte have over a century of organizing work. They really talked about how all of these folks who are in the philanthropic world, the foundation world. They were literally at a foundation, calling out the foundation world and saying, "Y'all act like y'all doing something special. This is what you're supposed to do. That's our money. That's the people's money. All these billions of dollars foundations have, that's our reparations money, that's money that is owed to the people for the systems that we are struggling to survive in right now, which many folks have actually capitalized on and profited from, that needs to be returned to the folks."

The systems of genocide, slavery, white supremacy, and capitalism that have generated billions of dollars of wealth on the backs of Black people, Indigenous people, and working in poor folks, those systems have generated wealth that needs to be reallocated to those folks who are most marginalized and most oppressed. They spoke that truth so powerfully, called out the non-profit industrial complex in a way that was undeniable, and a way that you can only do that where you're at that point, Dolores was 83, and Harry was 86. In their 90s now, they're still talking the talk and walking the walk.

Melissa: Track two really had me thinking. You have a conversation in here with Albert Woodfox. I'm a North Carolinian, I know Woodfox's story well, I don't know how much other folks know. Tell us a bit, remind us who Albert Woodfox is.

Bain: Yes, Albert Woodfox is the longest-held solitary confinement survivor in United States history. He did 44 years in a six-by-nine box in the Angola penitentiary. For those who don't know, the Angola State Penitentiary, formerly called the Louisiana State Penitentiary, is called the Angola State Penitentiary because it's where those enslaved Africans were taken from, from Angola to be put on to forced slave plantations owned by a Virginia plantation owner that after the Civil War, went from a plantation to a penitentiary. They basically just changed the sign on the door from Angola State Plantation to Angola State Penitentiary.

Albert was one of three brothers we know as The Angola Three who stood up against what was happening in the prison. He said, "We are sick and tired of seeing these young men and boys come in here and get raped." Over 200,000 men are reportedly raped in prisons around the country. That's not even counting the women, it's not even counting those who have not reported.

When they said, "Enough is enough," they started the first Black Panther chapter in the largest prison in the country, it currently has 6000 people at the prison. They were punished, they were punished for standing up for their basic dignity, for standing up against the sexual assaults that were happening in the prison, and his comrades were put into solitary for decades on end.

What is really a surprising thing for me, a big takeaway for me, a testament to the resilience of the human spirit of Black folks sovereign through the hells we've gone through in this country, is he came out after 44 years, and he came out somehow better and not bitter, and on a mission with a cause to bring to the world's attention that solitary confinement is inhumane and should not happen for even a day, not 15 days as the UN has decided is torture, but not for a single day.

We treat human beings worse than animals in the zoo. That's what happening right now in the largest prison in the country. Albert Woodfox is speaking his truth around the world to let folks know that solitary confinement must be abolished.

Melissa: On the third track, you go to Ms. Susan Burton, who I've had just the incredible pleasure of speaking with many times. She is that stark reminder, as you spoke on Dolores Huerta, that these injustices are so frequently presented as though they are gendered male, but they are not exclusively gendered male. Tell me about your takeaway from Ms. Burton.

Bain: Well, Ms. Burton was one of the first folks I met after moving to LA in 2015. I learned very quickly why folks call her the 21st Century Harriet Tubman. Susan Burton had her son killed by the LAPD at five years old, and unsurprisingly spiraled into alcoholism and addiction and found herself in and out of prison over the course of two decades. She was devastated.

Somehow she also found the resilience, found the community support, and spirit to actually rise up out of that and to become a beacon, a safe haven for women coming home from prison. Many folks don't know women have been the fastest growing demographic to be incarcerated for several decades now.

Susan Burton has been one of the few folks who built a whole organization, a New Way of Life Reentry Project in South Central, Los Angeles, modeled now in four states around the country, there's other models based on New Way of Life coming up. She has shown us that with the proper networks, the proper support, the property community backing, that folks who come home can stay home, and women need to be focused on.

This is something that the research bears out. We know that when we invest in women, we invest in community, we invest in family. Muhammad Yunus's work showed the women actually returned their bank loans more because they didn't go drink and gamble the money off like the men often did. In Susan's living example, she shows that investing in women goes a long way. It's a model that needs to continue to be emulated around the country.

[music]

Melissa: Let's pause here for a moment. More Bryonn Bain social justice mixtape in a moment.

[music]

Melissa: I've been speaking with scholar and activist Bryonn Bain about his book, Rebel Speak: A Justice Movement Mixtape. Now, Rebel Speak is built around a series of conversations that Bain conducted with social justice leaders for many different generations. Together, these tracks reframe many of our society's commonly held beliefs about what justice looks like.

In the fourth track, you engage the work of the late Lani Guinier and have us think about mental health and trauma in the context of mass incarceration. What is your track four takeaway?

Bain: Melissa, for a long time, I really thought mental health was something white people talk about. I was like, "Are you going to a therapist, you're going to a counselor? You must be crazy." Now I know if you're not seeing somebody, not talking to somebody about your problems, you actually might be crazy because you're not doing that.

I really learned a lot about mental health through Lani. Lani came to Harvard Law School same time I did. I learned about Critical Race Theory, Critical Gender and Class Theory from Lani. I learned it's something that's in law schools, which most folks from my country don't talk about. It actually should be in not just law schools, but in colleges and in high schools and in middle schools, folks need to be learning about Critical Race Theory and Critical Race studies around the country.

Lani showed me that. Seeing her in her last few years, have the experience of developing Alzheimer's and seeing what that meant, the loss of memory, the loss of family, the things that meant so much to her and made her who she was, made her one of the top voting rights expert in the world for a very long time, first Black woman to be tenured professor at Harvard Law School.

She was like Auntie Lani to me. She took care of me in one of the most alienating environments in my life. Lani took me under her wing and really showed me so much love, and so to see her have her own mental health challenges really opened up for me the need for all folks, Black folks, Latinx folks, queer folks, folks who are experiencing--

We all experience trauma. If we do not find ways to address our trauma to actually develop healing modalities to look at our trauma, regardless of our race, our gender, our class, we're going to suffer from that and continue to suffer from that. Lani's experience, my experience with Lani, the love she showed me, and the last years of her life, we bid her farewell just this January, and it was a heavy loss, but I've learned so much from that. I weaved in the voices of other folks I've learned from.

It's truly an intergenerational mixtape because you have folks like Lani and their inspiration, their influence on me, and then you have all the folks in this generation and the generation Z and the millennials, who are all involved in this global movement to reimagine justice.

Melissa: Your fifth track is beyond the bars, and bars here, you're clearly taking multiple meanings because you start delving a bit into art with these conversations with Jennifer and Wendy. Tell us about them.

Bain: Wendy and Jennifer were two of the brilliant students in the very first classes that I started at the California Institute for Women, the oldest still functioning prison for women in the State of California. They both have come home, and they've had serious struggles. It's not been easy.

I remember I walked into CIW prison, and I heard they were singing in the auditorium. I was like, "Nobody told me Beyonce was up in here." Wendy was leading the choir. [laughs] Blew my mind. So much talent. Jennifer was someone who had doubts about her ability to be in a UCLA class, being she'd only had community college up to that point, but then she became really the leader of the group, the creative writing workshop that adapted this hip-hop theater, spoken word version of The Wiz that I've written with former incarcerated folks on the East Coast.

We adapted it on the West Coast and performed it. They got to come and see it at UCLA after they were released with the Last Poets opening up the show, Rosario Dawson in the audience that day, and just to see 500 people in the room performing work that they worked on while they were incarcerated. It was a really special experience for us to share.

Their story, when they came home, it was really important to me to sit down and just process with them what the difference was between their life now, what their life was before, to really give some insights into other folks coming through the pipeline, who actually are coming home and trying to stay home and try to learn from the lessons of other women who've had their experience.

Melissa: I think one of the, I don't know, maybe most surprising aspects of this mixtape is this conversation you have with the Warden of Sing Sing. Go ahead and tell me about this.

Bain: This is what Angela Davis, who I was so blessed to have write the foreword for it. She talks about this chapter as an outlier. She says, "Even in the mixtape, you might have some things that go against the grain of everything else in there, but it helps you to see things in a different perspective."

The Warden of Sing Sing, you would not think of a warden as somebody who's a rebel. This warden, who I know because Harry Belafonte actually brought me in. He brought in folks like Whoopi Goldberg and Julian Bond. I think Usher was there last time I was there. He brings in all these folks. I brought in Deebo from Friday. We did TED Talk before Deebo passed. I brought him in, and the brothers were so open that we brought Deebo in.

This warden has been particularly open to arts and education. I did TED Talks there with Academy Award winner, Jonathan Demme, directing before he passed. We've done a lot of work with Carnegie Hall there, a lot of innovative programs. Sing Sing is the closest prison to New York City. It's 56 minutes off of Metro North up in Ossining, New York. It's the maximum security prison that folks prefer to be in because it's closer to home if you're in the five boroughs.

He's led a lot of projects and programs that many other prisons have not. Changes are happening now, but for years, for decades, he's been doing that. One of the things that really got me thinking he should be a part of this conversation is that there was an incident where the COs, one of the guards in the prison, was caught on tape violently beating one of the incarcerated men, and Warden Capra actually went and testified against his own CO.

That was a move that he was certainly not celebrated for when he first came to the prison. He was a New York City cop. He took pride in kicking down doors and all the things that Black folks trying to stay away from. He was applauded when he walked in, but after he testified against his own CO, his own prison guard, folks didn't want to look at him, didn't want to have too many words with him. He had to go back, and he's still there now doing the job.

Because of that experience, this was the week after he testified, I said, "We need to have a conversation. What was that about?" We got into it. I was able to ask him questions that I've been thinking about for a long time, like why is it that in most of Europe, the life sentences are not for life. It's 20 years max. I think the fact that they have something that doesn't look like our prisons here at all. It's not the largest number of people incarcerated, being tortured, and terrorized in these human cages.

He said they have not had the history of different racial groups, basically, and that the conflict between different racial groups that we've had here. That was interesting because he didn't-- I wouldn't have said it that way, but it did get me to begin to think and reflect more deeply about how the history of racial violence in this country has never been dealt with.

Even this reckoning over the last two years has been a reckoning mostly in rhetoric more than in substantial structural changes, more than in the redistribution of resources and wealth and power and privilege that's really necessary. That conversation with Warden Michael Capra at Sing Sing helped me to bring a lot of things to light by seeing how he sees these issues through his eyes.

[music]

Melissa: Bryonn Bain, thank you for Rebel Speak: A Justice Movement Mixtape. Bryonn is, of course, not only the author of Rebel Speak but also co-director of the Center for Justice at UCLA. Bryonn, thanks for being here.

Bain: Thank you so much, Melissa.

[music]

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.