"Readiness” for Peace Still Exists Between Israelis and Palestinians

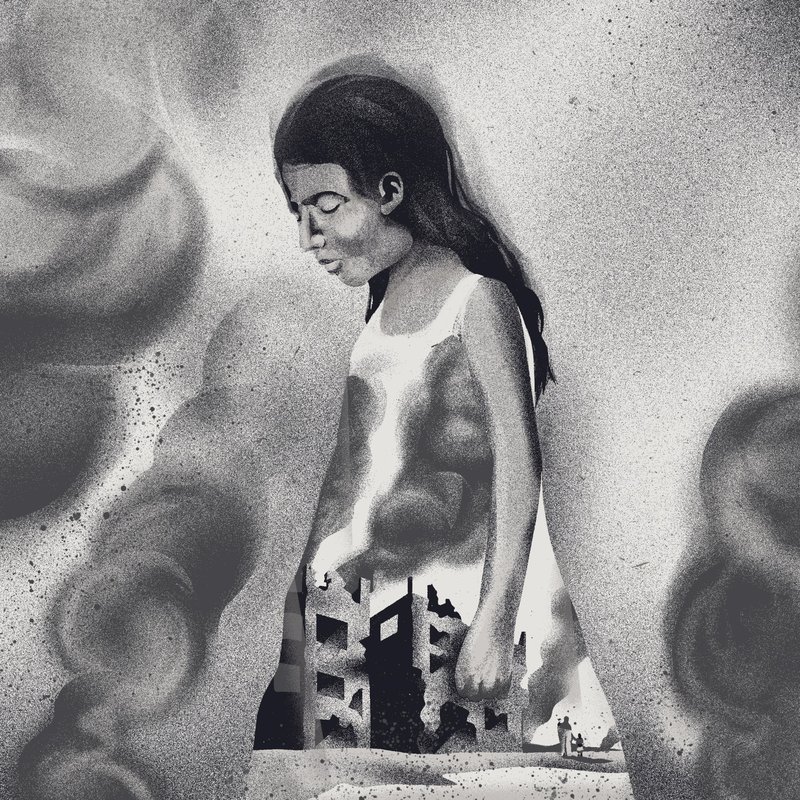

Mosab Abu Toha: The houses in Jabalia refugee camp are too small that the street becomes your living room. You hear what your neighbors talk about, smell what they cook. Many lanes are less than a meter wide.

David Remnick: A few days into the Israeli siege of Gaza, we received an essay from a Palestinian writer named Mosab Abu Toha, a poet. He lives in Gaza, and his family took shelter in Jabalia refugee camp. Abu Toha's account is called The View from My Window in Gaza, and he recorded an excerpt for us.

Mosab Abu Toha: After two days in the camp, on the Saturday morning, my family has no bread to eat. Israel has cut Gaza's access to electricity, food, water, fuel, and medicine. I look for bakeries, but hundreds of people are queuing outside each one. I remember that two days before the escalation, we bought some pita. It is sitting in my fridge in Beit Lahia. I decided to return home but not to tell my wife or mother because they would tell me not to go.

The bike ride takes me 10 minutes. The only people in the street are walking in the opposite direction, carrying clothes and blankets, and food. It is frightening not to see any local children playing marbles or football. This is not my neighborhood, I think to myself. On the main street leading to my house, I find the first of many shocking scenes, a shop where I used to take my children to buy juice and biscuits is in shambles. The freezer, which used to hold ice cream, is now filled with rubble. I smell explosives and maybe flesh. I ride faster. I turn left toward my house.

David Remnick: The poet Mosab Abu Toha, writing in the first days of the siege of Gaza. You can read The View from My Window in Gaza in its entirety at newyorker.com.

[music]

20 years ago, I wrote about a man named Sari Nusseibeh, who's been involved in efforts for peace in a Palestinian state for many, many years. Nusseibeh comes from an old and prominent Jerusalem family, and he's a professor of philosophy, early Islamic philosophy. When I profiled him for the magazine in 2002, Nusseibeh was a counselor to Yasser Arafat and certainly one of the most moderate people in the circle of the Palestine Liberation Organization. He is uncompromising in his insistence on Palestinian independence and dignity, and yet he's able to acknowledge reasons for Israel's anxiety over security. His disapproval of violence, whether perpetrated by Israeli settlers or Palestinian suicide bombers, is absolute.

I met up with Sari Nusseib again this month in East Jerusalem. I was trying to understand how the October 7th attack would change the trajectory of the larger conflict in the region, and we followed up on Zoom last week.

Sorry, we've just had a conversation in Jerusalem, but there are things I want to ask you. Do you think the massacre of October 7th was a unique event? Israelis are comparing this to some of the great tragedies of Jewish history, about the Kishinev massacre, about things that go back centuries and there's a particular aspect of cruelty that Israelis talk about. How do you view it?

Sari Nusseibeh: Well, look, I'm not going to deny that human nature is not all good, and some of it is morbid. In general, the massacres and the problems that the Jews had in Europe were really exceptional. They were not to be compared with their history in the context of the Arab world. Now, I'm not saying that there was nothing done to Jews in the duration of the Muslim and Arab world back to the sixth or seventh centuries, but there was never this kind of anti-semitism and this gleeful desecration of Jewish values, Jewish life, as it has been the case in the Western countries.

The problem that we as Arabs, Muslims, and Palestinians have with Jews has nothing to do with their being Jews. It has to do with the political conflict we have with them now on this land. I think there's a major difference. I can see in fact that there is anti-semitism still alive in the West, but it's not the kind of anti-Israelness that I can feel here among Palestinians or in the Arab world.

David Remnick: The original Hamas charter, was deeply anti-Semitic, not much different from Henry Ford or some of the famous documents in anti-Semitic history, that was revised in 2017. How do you view Hamas's particular view on this score?

Sari Nusseibeh: Well, I think that Hamas, as you know, derives from initially as an ideological Islamist movement from the Muslim Brothers. That movement is a newcomer in a sense into the Arab world. You have a mixture. You have the mixture of Islamism on the one hand, and that radical ideology, extremist ideology, and then you have the national ideology, and they mix together Hamas. I see it as part of the texture of our society, but not as one that is necessarily deep in society and not necessarily one that can or should remain to be dominant in our society. You can always have radicals in any society, but I think that they should be controlled.

David Remnick: Now you live in Jerusalem. You have lots of people that you know in, well, all over the region, all over the world, as a scholar, but particularly in the West Bank and elsewhere in the Palestinian community. You seem to tell me the other day that the reaction to October 7th went in stages. That it was not one particular reaction, it evolved as the news came out.

Sari Nusseibeh: There was a disbelief that there was anything serious happening. Then there was the shock that there was something very major happening, which is the crossing over, breaching the wall, and the security belt that Israel had put up. Nobody actually expected this could ever happen, and indeed it never happened in the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Then came the explanation that this was Hamas militants going and sort of having shootings with the Israeli soldiers and taking places over. Then there were the news or the views of the people who came into the Israeli area in the footsteps of the Hamas militants. There were a lot of people that just poured in from Gaza. The distances are very short, as you know.

David Remnick: Just a mile or two, yes.

Sari Nusseibeh: There was a lot of just taking stuff from the kibbutz and the settlements that they could lay their hands on.

David Remnick: You're describing looting?

Sari Nusseibeh: Looting, yes.

David Remnick: Just to break it down, I think what you're saying is initially there was shock but also a degree of celebration at the fact that they broke through, and then when they saw the nature of the violence, there was something else, a different kind of reaction.

Sari Nusseibeh: Yes. As the different media came through, you were not only seeing the Palestinian but also the Israeli point of view. There were clearly problems. People started questioning the nature of what is happening to the Israeli civilians themselves. Of course, when the news came out from the Israeli side that there were massacres and lots of people killed-- By the way, to tell you, this wasn't something that on the Palestinian side was taken as necessarily true that there were so many people killed or so many civilians killed. Day after day, people stopped, looked again at the scenes, and decided, yes, there must have been wholesale killings of people, civilians, and that raised, of course, worries and concerns among a lot of the people who were very much in favor of the breaching of the security wall in the first place.

David Remnick: What were the worries? Was it moral concern? [crosstalk]

Sari Nusseibeh: Yes, a moral concern. Things were going out of hand. This is not what should be happening. It is not something that people associate the better natures with you. The thing is that you can't really dissociate between the two. You have a conflict. You have people killing each other. You may be happy that your side is doing the better killing of soldiers on the other side, but then there are the civilian casualties. I think there's even more knock realization that no, this was definitely a crime to go around killing people like that.

David Remnick: Occupation has been going on now for 56 years. Some people still argue that there were opportunities for peace. You have deep roots in the national movement. At one time you were even an advisor to Yasser Arafat, a distinctly moderate one. People say, look, they were not perfect agreements. They were flawed in many ways, but they look back and all these opportunities seen in the rearview mirror to a lot of people, like totally missed chances. Do you agree?

Sari Nusseibeh: I agree. I mean missed chances by both sides, by the way, because it was always, is now also, and will be in the future, in the interest of the two sides to actually make peace together. I feel that only two sides have always been the readiness to make peace, but every time they took steps forward towards one another, they just didn't make it. They gave up very quickly. For instance, in Camp David 2000, they got together and then each side went out to the room by themselves. Clinton came out against everybody, the Palestinians, the Israelis. Barak came out against Arafat. Arafat came out against the Israelis and Americans.

The population that was ready at that time for a peaceful solution between the two sides suddenly was thrown into the black hole of the universe. By the way, the populations have over time consistently been ready on more than one occasion. For instance, I remember after Camp David 2, the initiative it was a grassroots informal initiative that I participated in with an Israeli counterpart [unintelligible 00:13:22], you probably know him to get signatures from both sides on six principles. It's half a page paper on six principles.

They had more than a million signatures that's total between Israelis and Palestinians. Can you believe that? This is one single document. No other document actually had as many signatures, but it was a time when in theory, people were apart from one another. I think it's the responsibility of the leaders when they get to the point to actually, what you say to make a closure in the deal between them. The example between Olmert and Abbas is one such example. There's no reason why it shouldn't have just been built upon. Why they couldn't have met the following day and the day after that, and why they couldn't have pursued it.

David Remnick: I'm speaking with Sari Nusseibeh, a professor and longtime diplomat involved in peace efforts. We'll continue in a moment. This is The New Yorker Radio Hour.

[music]

David Remnick: This is The New Yorker Radio Hour. I'm David Remnick, and I'll continue now with my conversation with Sari Nusseibeh, who had been an advisor to Yasser Arafat and the PLO, certainly one of the most moderate in the circle. He's a professor of philosophy and a former president of Al-Quds University as well. Sari, you express a degree of optimism that people, that both populations are always eager for a peace agreement. At the same time, we've just seen what happened on October 7th, and in the aftermath. We're watching a horrific bombardment of Gaza now and a probable ground war.

On the Israeli side, the government is more reactionary, more right-wing, more pro-settler than ever before in Israel's history and Hamas remains as a dominant force, a fact of politics in Gaza and even the West Bank. In fact, you said something very interesting to me the other day, that Hamas is more popular in the West Bank and the Palestinian Authority is more popular in Gaza. The reason is matters of governance. The whole recipe, sorry, does not bode well to me for a peace settlement.

Sari Nusseibeh: Apparently, that's how it is. The popularity and lack of popularity has really more to do with governance. How the different authorities are governing their constituencies and the sense that they're not doing all they can. Look, people get very angry. I can understand the Israelis and the Palestinians now, today wanting vengeance and wanting to regain the image they have of themselves and wanting their rights and all of that. I think both peoples know deep down that it doesn't lead anywhere to continue shooting at each other, and that there must come a point when they have to come to terms with one another and to find some kind of form of coexistence between them.

Although the Israeli population has been pushed to the right and on the Palestinian side, have been pushed towards Hamas. Nonetheless, I think this is a temporary thing. I think that they will come soon when it'll be possible again to build for peace. It can be done with sufficient also help and intervention by the international community.

David Remnick: The other day you said to me that the idea that Israel thinks it can eradicate Hamas is a delusion, and you said instead of thinking you can shoot and kill them, you can reverse the situation by refusing to shoot, by giving the other option the air it needs. You get what you want by addressing the national concerns, and Hamas, in a sense, would wither away.

Sari Nusseibeh: Hamas represents what you might call active resistance to the occupation in the Palestinian community. The Palestinian Authority, if you like, represents the pursuit of the dream of a peaceful solution with Israel. Now, these are the two options that we have before us. If the peace option succeeds, I think that the support that Hamas has as a movement that wants to continue to have active resistance will simply die down. I'm not saying that everything to do with Hamas, their ideas, the Hamas people who support it will disappear. I think they will be reduced once again, like they did before, to a kind of acceptable minority in the community.

Likewise in Israel. In Israel, you have a radical right now in control but I think it can be reduced, not necessarily wiped out, but reduced to have a role within the overall context of a population that's driving towards peaceful relations with its neighbor. Everywhere where the governments are not actually addressing the people's needs, is going to be a situation. There's going to be a situation where people will rise up against that government. You have to have governments that actually are governments there for the people, that they respect the people, they respect their dignities, and they offer the services and the needs that they want. That's not what you find in the Arab world today, in general.

David Remnick: The other day I spoke with David Grossman, a great novelist. David said that this is going to intensify the right-wing drift in Israel. There'll be more valorization of the army despite the army's failures. He was very pessimistic. Also, Israel, considering the geography of where it is, while being a power compared to the Palestinians regionally feels under assault. All this also augurs, at least in the short term for an extended period of not only violence in Gaza, but of a weariness of any kind of settlement with the Palestinians.

Sari Nusseibeh: Well, I agree that in the short term, this is exactly how the Israelis now feel and will continue to feel concerning the army, concerning the security, and so on. Also in the short term on this Palestinian side, also people will feel Palestinians have to be revenged, military resistance has to continue, and so on. I think it will not be like that in the long term.

At the end of the day, whoever you are on the Israeli side, from the extreme right to the extreme left, or on the Palestinian side, whoever you are, you really want to have a nice, common life to live. You want to feel secure about your children. You want to have their schools over there, and you want to have their gardens in public space. This is what you want. This is true of every Israeli, including the most extreme of them, and of every Palestinian, including the most extreme Hamas, if you like militant of them. You have to give them options. People have to be shown or provided with options.

David Remnick: You don't think there'll be a wider war, a regional war?

Sari Nusseibeh: It's quite possible. It's quite possible. If Iran and Hezbollah and I don't know what, they're going to become involved, yes, it will turn into a Third World War. I hope it does not, and that people have enough sense to contain it, who are in leadership positions everywhere. I hope people will come to their senses and try to temper down the emotions surrounding what's happening now.

That some ceasefire will be reached with people in Gaza and on the West Bank, and some vision of a possible peace in the future can be presented that needn't be implemented immediately, but that can be shown to be workable, and shown to be one that addresses the concerns of the Israelis and the Palestinians. We have to work in order to bring it about. We don't have the option of being pessimistic, David, really. We can't sit back and say, "That's it." We have to continue working in order to make it happen.

David Remnick: Sari Nusseibeh, thank you so much.

Sari Nusseibeh: Okay. Thank you, David.

[music]

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.