Re-Sorting the Shelves: A Look at Bias In the Dewey Decimal System

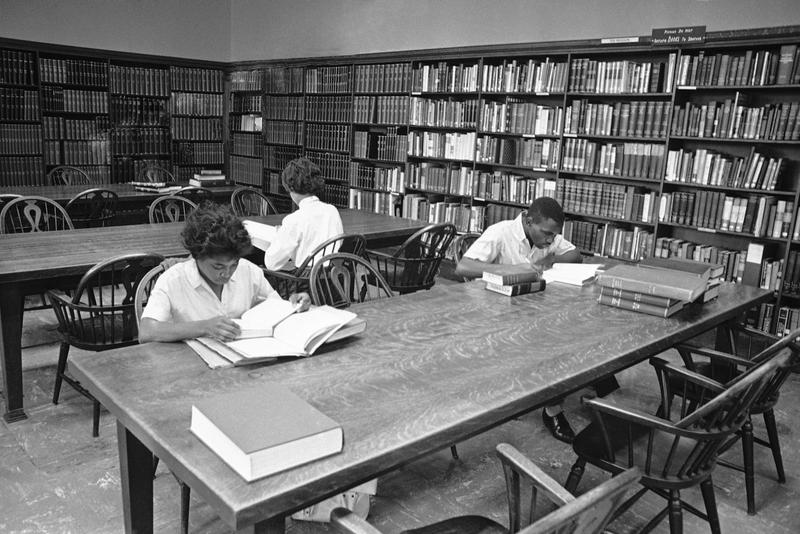

( Horace Cort / Associated Press )

Brooke Gladstone: I'm Brooke Gladstone, and on this week's midweek podcast, we bring you a contemplative retreat from the midterm news with a story that first ran last year. On the Media producer Molly Schwartz tells us the tale of how power has become entrenched quietly through standards in a quiet place — the library.

Jess deCourcy Hinds: I've been there 12 years.

Molly Schwartz: Jess deCourcy Hinds is a writer and the director of the Bard High School Early College Queens Library.

Jess deCourcy Hinds: I founded it. I started it from the ground up.

Molly Schwartz: As the solo librarian, she has to do everything herself, including catalog all the books using the Dewey Decimal System.

Jess deCourcy Hinds: We librarians who work with Dewey are well-versed in these numbers.

Molly Schwartz: For all the non-librarians out there, a quick primer on the Dewey Decimal System.

[CLIP]

Archival Clip: Have you ever watched the way others use the library? There's quite a difference in the way they go about it.

[END CLIP]

Molly Schwartz: It's organized into 10 main classes of knowledge with each class represented by numbers. Philosophy and psychology are the 100s. The 200s are religion. Social sciences are in the 300s; the 400s are language, and the 500s are science. Catalogers can add more numbers to make a Dewey's number more specific to the book it's describing.

[CLIP]

Archival Clip: Each figure in the number is significant. 510 tells us the books deal with mathematics. 520 tells us the books deal with astronomy. 530 is physics.

[END CLIP]

Molly Schwartz: Rounding out the 10 main classes are technology, arts and recreation, literature, history and computer science and other information. It's a hierarchical structure in which all of these classes have nearly endless permutations.

[CLIP]

Archival Clip: You'll be looking for many books in the 800. Do you know what they are?

Archival Clip: Literature.

Archival Clip: That's right. 810s are American literature. 820s are English literature. 830s are--

[END CLIP]

Molly Schwartz: One day in 2010, the Bard High School Early College Library received a large order of books about the Civil Rights movement, which Jess deCourcy Hinds was excited about because:

Jess deCourcy Hinds: Our history section was feeling very white.

Molly Schwartz: But when this big order of Civil Rights books came in, she noticed they weren't classified under history in the 900s but under the 300s.

Jess deCourcy Hinds: The 300s are a grab bag of books.

Molly Schwartz: They include everything from anthropology and sociology, labor studies, political science and folklore, but also some books that could possibly be classified in the 900s, the history section.

Jess deCourcy Hinds: Books on Obama were in 300s. They were separated from books on other presidents, and that was very disturbing to me. And I just didn't understand why our current president was not going to be part of history.

Molly Schwartz: And Obama wasn't the only one stuffed in the 300s.

Jess deCourcy Hinds: When it came to the LGBTQ books and the women's history books and books on immigrant history — all of those were in the 300s as well, and I realized that women, immigrants, and people of color were all being pigeonholed in this very strange 300 section, so we just started moving them.

Molly Schwartz: She and her student interns decided to put President Obama where they thought he belonged, in the 900s next to the other presidents.

Jess deCourcy Hinds: That was the beginning of changing Dewey, of rebelling against Dewey.

Molly Schwartz: deCourcy Hinds wrote about her frustrations with Dewey in a New York Times essay called “Oh Dewey, Where Would You Put Me?”

There have been critiques of Melvil Dewey and his system dating back to the early 1900s, and recently some libraries have been ditching Dewey in favor of bookstore-style organization.

[CLIP]

News Clip: Public libraries are rolling out a new system where books are now organized by categories such as animals or computers.

News Clip: People don't come in and go, "I feel like an 811 today." No, they think, "I want poetry."

News Clip: The Greenwood Public Library's ditching Dewey for a shelf system they call Subject Savvy.

[CLIP]

Molly Schwartz: For most of the Dewey Decimal System's 145 years in use, Melvil Dewey has been celebrated as a kind of founding father of American librarianship.

Wayne Wiegand: We're always searching for heroes, and Dewey was an early library pioneer whose influence was very wide.

Molly Schwartz: Wayne Wiegand is a library historian and the author of Irrepressible Reformer: A Biography of Melvil Dewey.

He describes how Melvil Dewey created the Dewey Decimal System in the early 1870s when he was a student at Amherst College.

Wayne Wiegand: The Amherst College campus between 1870 and 1874 was a very white Anglo-Saxon, Protestant, male-dominated world. Dewey pretty much programmed into his system the priorities, of course, which brought also the biases and the prejudices of that world, into his classification scheme. You can tell this very easily in the 200s in the religions, which heavily privileges Protestantism against all other kinds of religion.

Molly Schwartz: In fact, nine-tenths of the 200s are dedicated to Christianity. Like David Starr Jordan, who Lulu Miller wrote about in her book, Melvil Dewey was a late 19th-century eccentric who loved to classify things. In fact, the lives of Melvil Dewey and David Starr Jordan have some other eerie parallels.

They were both born into strict Protestant households in upstate New York in 1851, and they both died in 1931. Dewey also had views that made him, if not an outright eugenicist, at least eugenics-adjacent.

Wayne Wiegand: He was certainly sympathetic with the ideas that the eugenicists put forth. He did not see Black people as equal to white people. He did not see Jewish people as equal to white people.

Molly Schwartz: Books by Black authors were classified in Dewey under slavery or colonization, even a book of poems by James Weldon Johnson, a famous Black writer. When LGBTQ topics get Dewey numbers in the 1930s, they're categorized as abnormal psychology, perversion, derangement, and medical disorders.

Emily Drabinski: That system will reflect the ideology of the people who designed it.

Molly Schwartz: Emily Drabinski is the interim chief librarian of the Mina Rees Library at CUNY.

Emily Drabinski: You can add new language and revise old language, but essentially, you are always putting a new item into a preexisting system.

Molly Schwartz: The Dewey Decimal System is like the original YouTube algorithm. Its power comes from the fact that it groups books next to other books on related subjects so that when you're browsing the shelves, you're basically recommended other books you might like. Dewey wasn't the first person to think of this idea, but he was a brilliant businessman who found himself in the right place at the right time.

Wayne Wiegand: Andrew Carnegie was donating millions of dollars to put up thousands of public libraries across the country, and it was in a rare community that did not have a public library by 1920.

Molly Schwartz: Dewey was poised to supply them with an organizational system and an army of librarians to implement it.

Wayne Wiegand: And his scheme was there, and it was being promoted by his students and the library press and the library organizations.

Molly Schwartz: For Dewey, his classification was always meant to organize all the knowledge in the world, but of course, times change, new technology gets invented, cultural norms evolve, geopolitics shifts, so the Dewey Decimal System is regularly revised. For a long time, those revisions happened within a kind of black box, but according to Caroline Saccucci, who works at the Library of Congress where she spent nine years as the Dewey Program manager, it's become more democratic over time.

Caroline Saccucci: A lot of work has been done to really promote this community engagement aspect for the Dewey classification, which I think can only make it better and make it stronger and have community members take ownership of it as well.

Molly Schwartz: Since 2019, proposed Dewey revisions are posted online and open to public comment. Librarians can even contribute Dewey numbers back into the system. Of course, an especially frustrated librarian can always just go rogue.

Caroline Saccucci: There's no library police that can come out and tell the library they've done it wrong. Libraries are always free to arrange materials according to the way they want them and that will best serve their users.

Molly Schwartz: That's easier said than done.

Caroline Saccucci: Anytime there's a major change to a classification system, it could [wreck] havoc with the collection because it means that all the bibliographic records have to be changed, but then all the physical items have to be re-labeled and then re-shelved, and then signage has to change. There's just a whole lot that has to happen in order to reclassify large swaths of material.

Molly Schwartz: Aside from Dewey, there are other library classification systems, including the Library of Congress Classification System. It's one of the other largest systems in the world, and it's the brainchild of another white man that's beset with some of the same problems as Dewey.

Emily Drabinski: The Library of Congress Classification System comes from Thomas Jefferson's collection of materials. The Library of Congress, the initial collection for Congress burns down; Jefferson makes a donation to the state of his personal collection, and the classification reflects his original order for his own materials.

Molly Schwartz: Instead of using numbers to classify books, the Library of Congress system uses subject headings. In 2014, a student at Dartmouth College named Melissa Padilla was doing a research project on undocumented youth organizing. She went to meet with Jill Baron, a Dartmouth librarian, to find resources, and they noticed a subject heading that Melissa found disturbing.

Jill Baron: There were pages and pages of variations on the term "illegal aliens.” This was the term had been used to categorize this particular book.

Molly Schwartz: That's Jill Baron in the documentary Change the Subject. A group of Dartmouth students protested the use of the term "illegal alien,” but they discovered that the problem wasn't with Dartmouth.

Jill Baron: We didn't realize that it was like a national database that applied to every institution. It was, in some ways, our naive understanding of systems.

Molly Schwartz: So the students filed a petition with the Library of Congress to change the subject heading and the revision was accepted, but this was 2016, a year when the question of immigration was at the center of a contentious presidential race. Republican members of Congress got wind of the proposed change and decided to block it.

[CLIP]

Reporter 3: Cruz, one of four Republican lawmakers to sign a letter urging the Library of Congress not to eliminate the term "illegal aliens" from search terms and cataloging.

[END CLIP]

Molly Schwartz: Here's Diane Black, a then Congressional Representative from Tennessee.

[CLIP]

Diane Black: Can you believe that the Library of Congress would make a decision with a bunch of liberal students from Dartmouth University who sent a petition to them to say that this was a dehumanizing or an inflammatory term? And take that decision on political correctness to change something that has been in the lexicon there at our Library of Congress since back in the early 1900s is just unbelievable to me.

[END CLIP]

Molly Schwartz: The change was successfully blocked and to this day, "illegal alien" is still an official term in the Library of Congress subject headings, but the incident breathe new life into a movement among librarians who want to reform cataloging, even when that requires working through slow-moving bureaucracies.

Emily Drabinski: It's an intellectual infrastructure.

Molly Schwartz: Emily Drabinski.

Emily Drabinski: Most people don't even know it exists, much less get exercised about it. It's an incredibly difficult ship to maneuver.

Molly Schwartz: In 2013, Drabinski published an article called “Queering the Catalog: Queer Theory and the Politics of Correction.” She considers herself part of a group of so-called critical catalogers, but libraries with their committees and careful processes are a poor match for the speed at which cultures change and evolve.

Emily Drabinski: You have a system that cannot keep up with the rapidly changing language that LGBTQ+ people use to describe themselves — So that you'll have remnants of old language, and that will be the only language that's there, so “gay men,” “lesbian,” but there are many, many other words for people in the contemporary moment, and none of them are in the system. The language is never right; it's never correct, because it's always delayed, if language could even be correct in the first place, which I think it probably can't.

Molly Schwartz: She points out that in the Library of Congress Classification System, the one her library uses, the problem isn't only how things are named, but that some things aren't named at all.

Emily Drabinski: Another example of how bias is in the system is if I want to look up “African American women's history,” I do a search and it comes up. What if I wanted to do research into the history of white women? “White” is an unmarked category. It doesn't even appear. It's impossible to retrieve, so the normal is not named at all.

Molly Schwartz: For decades, proponents of critical cataloging have been showing the ways that library classification reflects systems of power that are at play outside the library walls and also reinforces them. Some librarians critical of classification systems want to burn them all down and start over, but they're not in the majority.

Emily Drabinski: I always wonder when people say, "Burn it down," if they've ever built anything. It can be very, very difficult to build things. The interoperability piece is super important, and if we want libraries to be able to share, we need those systems to continue functioning.

Molly Schwartz: Part of the reason classification is so problematic is because it's inherently reductive. Numbers and language are always flattening the thing they're trying to describe, shrinking big ideas into small codes that can fit on the spine of a book. Talking to library catalogers, I realized this isn't an exact science, it's a craft, one that's at bottom about making sure we have access to the ideas of others.

Emily Drabinski: The most magical thing that libraries do is share. I use OCLC and my records are there, and then I have colleagues on the other side of the planet who are using those same systems as well. It means that we can go back and forth borrowing and lending between each other, so that interoperability is really important.

Molly Schwartz: In a world without order, our classification systems will always be imperfect approximations, but the shelves of a library will always be a place that try to give our humanity some structure, some sense, or at least help you find the book you're looking for, which will have a call number on it between 0 and 999. For On the Media, I'm Molly Schwartz.

Brooke Gladstone: That was On the Media producer Molly Schwartz. Thanks for joining us for the midweek pod, and be sure to tune into the big show on Friday for a whole hour about America's newest battlefield, the library.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.