BOB GARFIELD: This is On the Media. I'm Bob Garfield.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And I'm Brooke Gladstone. Fifty years ago this week, just months before the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Supreme Court rendered a decision in the case New York Times v. Sullivan that would forever alter the way journalists practice journalism. Though the First Amendment had already been around for nearly 200 years, it was narrowly focused. News outlets could be shuttered if sued by public figures over minor inaccuracies. The stakes were thus very high in New York Times v. Sullivan.

ANDREW COHEN: This was a story about the civil rights movement. It was a story about the New York Times covering the civil rights movement, and it was the story of local officials, in this case in Alabama, trying to use state libel laws to essentially chill the press.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Andrew Cohen is a fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice and contributing editor at The Atlantic.

ANDREW COHEN: To force reporters either not to cover stories in the state or to cover civil rights stories in a way that was not true and more favorable to local officials than it was to the civil rights movement.

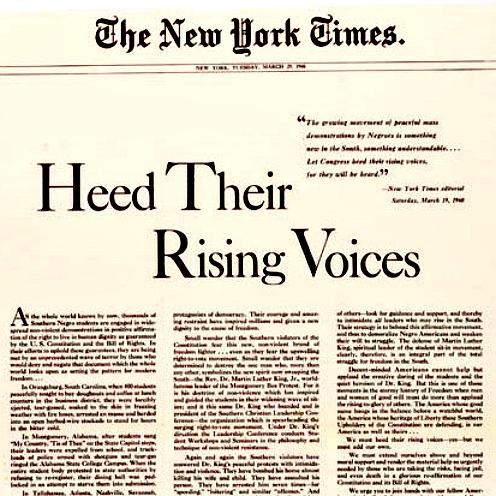

BROOKE GLADSTONE: It begins, as you note in your piece, in March of 1960, and it wasn’t about coverage, it was about a political ad that appeared in the New York Times, broadly criticizing Southern officials for their aggressive response to civil rights protests.

ANDREW COHEN: Right. It's a full-page ad, which essentially decries the actions of local officials in Alabama. It was signed by Martin Luther King; it was signed by Harry Belafonte and other notable civil rights leaders. The New York Times accepted the ad, and it turned out that there were certain minor inaccuracies in the text of the full page ad.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Like what?

ANDREW COHEN: Well, there was one sentence about the number of times that Martin Luther King had been arrested.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: A-ha.

ANDREW COHEN: The figure was off by two. That’s the kind of stuff that was cited by the Public Safety Commissioner in Montgomery, Alabama, a man named Sullivan who, although he was not identified in the ad, said that the Times had libeled him by publishing false material about him.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And the only protection against libel, at the time, was it had to be true. And, in this case, because there were a couple of minor inaccuracies, the Times couldn't argue that.

ANDREW COHEN: That's exactly right. At the time, the First Amendment and libel laws were essentially separate. No court had really firmly linked the two in the context of public officials. So you have this First Amendment that says, Congress shall make no law abridging free speech and of the press, and then you have these libel laws, which were essentially doing just that.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: How did Sullivan argue for defamation, if he wasn't even mentioned?

ANDREW COHEN: So what he was able to do, in Alabama, in the state courts, which, of course, were very favorable to him, is to say, the mere mention of the police, the word “police” linked him in the minds of readers. And that was one of the main contentions that the New York Times in - asserted as the case got to the US Supreme Court, that creating a libel liability in the context where you don't identify the person specifically who was libeled would generally preclude any criticism of any government action, anywhere, by any person working within that government.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So the Alabama state court decided in favor of Sullivan and then the Alabama Supreme Court upheld the decision. Let me play you some C-SPAN tape from 1991 of the late, great Tony Lewis, who had covered the case for the Times.

[CLIP]:

TONY LEWIS: Mr. Sullivan asked for $500,000 in damages, and a white jury, an all-white jury awarded him every penny of the $500,000. And others sued over the ad, including the governor of Alabama, total sum demanded, $3 million, and it was quite clear that if it were up to the Alabama juries, we’d be $3 million in the hole, the paper would. And the New York Times could not afford that kind of money then. It was a barely profitable newspaper.

[END CLIP]

ANDREW COHEN: It wasn’t just intimidating to the New York Times; it was an offensive weapon, if you will, by Southern politicians and Southern officials to try to financially freeze out the reporting that was occurring in the South at that time. There had been circumstances were reporters were basically not sent on assignments in the South because of the fear of these sorts of libel lawsuits. Had this ruling stood, coverage of the civil rights movement going forward would have been far, far less aggressive and, of course, that may have made a difference in the way that public perceptions were altered as a result of that coverage.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So, the Supreme Court took the case, heard arguments that you call “more intense and passionate than most.” We have some tape of Herbert Wechsler, who was the lawyer on the side of the Times.

[CLIP]:

HERBERT WECHSLER: This action was judged in Alabama by an unconstitutional rule of law, a rule of law offensive to the First Amendment and offensive on its face to the First Amendment. What it amounts to is that a public official is entitled to recover presumed and punitive damages subject o no legal limit and amount for the publication of a statement critical of his official action or even of the official action of an agency under his general supervision.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Now, arguing Sullivan’s side of the case was M. Roland Nachman, Jr., and he said that the precedent that would be set by letting the Times off would be far too dangerous.

[CLIP]:

M. ROLAND NACHMAN, JR.: We think that the defendant, in order to succeed, must convince this court that a newspaper corporation has an absolute immunity from anything it publishes. And we think that’s something brand new in our jurisprudence. We think that it would have a devastating effect on this nation.

[END CLIP]

ANDREW COHEN: You know, what he was saying was, don’t create this new rule. What the court did was to say, look, we are going to recognize a First Amendment protection here. Public officials aren’t going to have the same protection under libel laws that private people would have. And that means we’re going to allow the press to make mistakes. We’re going to hold the press to certain standards, actual malice, so we’re going to try to make it clear to news organizations that they have certain responsibilities to try to be accurate. But, when there is a mistake, we’re not necessarily gonna jump to a huge punitive libel award.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Talk to me about the actual malice standard. How is it applied and how is it argued?

ANDREW COHEN: Yeah, well that's a whole other conversation. [LAUGHS] The justices knew that they were extending First Amendment protections beyond where they had gone before, and so, they wanted to do it in a way that they thought fairly balanced the interests of news organizations and First Amendment interests, but also to make sure that certain libel actions could succeed, if there were particularly egregious factual mistakes or if there was some intentional libeling of a public official.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And so, the attorneys on both sides found themselves arguing the issue of intention. Here's Wechsler.

[CLIP]:

HERBERT WECHSLER: And at the time when the publication was made, the New York Times had nothing by way of information to indicate that the statements were false.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And, on the other side, Nachman, speaking for Sullivan.

M. ROLAND NACHMAN, JR.: We say that on the facts of this case that there was the kind of recklessness and abandon and an inability to look at facts before publication, which could be the equivalent of intent.

[END CLIP]

ANDREW COHEN: This was a weak case on the facts for Alabama, and you wonder if history would be different, if the decision would be different, had the advertisement been incorrect in more material ways. You see in the argument made by the Alabama lawyer, talk about recklessness, this is an advertisement, right, signed by leading figures.

The Times was essentially saying, we had no duty to give it the kind of thorough fact checking that we otherwise would, and to require us to have a duty to do this and to get every single fact right, in every single thing we print is simply something that the Constitution doesn't require. So you see in this exchange the recognition, I think, by Alabama [LAUGHS] that it wasn't gonna win this case on the facts. It was gonna win this case on the fact that the law had been a certain way for many, many decades and that it shouldn’t change.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: There was plenty of investigative reporting before Times v. Sullivan and lots of criticism of the government. So why was this so crucial?

ANDREW COHEN: Talk about the criticism of the CIA and the NSA and all of the major debates we have now, those debates would be very different if the public officials involved in them felt that they could sue successfully under state law to prohibit people from criticizing them for one or two or three minor mistakes. You know, sometimes when you look at the context of New York Times v. Sullivan, you don't wonder about the ruling, you wonder why it took so long.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

Six score, seven score, [LAUGHS] eight score years after the Bill of Rights is enacted, you have this very strong ruling that says, listen, there is a place in America for public dissent against public officials. They’re not going to be able to use these libel and slander laws as offensive weapons to chill speech.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And yet, there are states that have passed food libel laws, so if you say something bad about a piece of steak, you can get sued.

ANDREW COHEN: Yeah, those laws do implicate the First Amendment, in some respects. I think those laws are gonna be challenged. I think the Supreme Court is very different today, obviously, in terms of its ideology than it was back in 1964. But Sullivan is still good law.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Andrew, thank you very much.

ANDREW COHEN: It's my pleasure.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Andrew Cohen is a fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice, contributing editor at The Atlantic, and analyst for CBS Radio News.