BOB GARFIELD: This coming week, the Supreme Court of New Jersey will consider an appeal of a decision in 2008 that found Vonte Skinner guilty of attempted murder. On what evidence? Inconsistent eyewitness testimony and rap lyrics written by Skinner that spoke of violence and life on the street. The lyrics did not reference the victim or any details of the crime. In fact, they were composed before the shooting, in question. But they were still the central piece of evidence that put him behind bars for a term of 30 years.

Professor Charis Kubrin studies the surprisingly common use of rap lyrics as evidence, and countries wrote an op-ed in the New York Times last week called, “Rap Lyrics on Trial.” Charis, welcome to On the Media.

PROF. CHARIS KUBRIN: Thank you.

BOB GARFIELD: I’m no lawyer, but I have seen many, many episodes of Law and Order, and it seems to me that this is the very definition of prejudicial testimony. How did a trial judge ever agree to allow this as evidence?

PROF. CHARIS KUBRIN: The character evidence argument, that’s technically not the way in which they’re allowed to introduce the evidence, but they’re allowed to talk about the evidence as the dependent’s knowledge, motive or identity with respect to the crime. But the way it comes across to the jurors and everyone else involved is that this is sort of character evidence.

BOB GARFIELD: To the casual listener, I guess, it’s not an insane leap to imagine that a rap lyric may actually portray actual events, right, because –

PROF. CHARIS KUBRIN: That is correct, exactly.

[BOTH SPEAK/OVERLAP]

BOB GARFIELD: - part and parcel of a rap artist’s appeal is this whole notion of living the street life that he, usually he, is rapping about.

PROF. CHARIS KUBRIN: Correct.

BOB GARFIELD: But nobody thought Johnny Cash killed a man in Reno just to watch him die, and what may seem logical does not necessarily make it credible evidence.

PROF. CHARIS KUBRIN: People that listen to rap music generally know that a lot of this is marketing pose, that the very definition of gangster rap is to be over the top, explicit, violent, misogynistic. Unfortunately, people in the courtroom, including most jurors, themselves have no idea, because they’re not avid listeners or they don't necessarily appreciate the genre. Judges, prosecutors and others involved treat it as autobiographical confessions because the assumption is that what rap lyrics are is, in fact, these rhymed confessions.

BOB GARFIELD: I think the elephant in the room here is not only the legal question of what constitutes admissible evidence of state of mind, but race baiting.

PROF. CHARIS KUBRIN: Absolutely.

BOB GARFIELD: It sounds to me as if it's very easy to prey on the fears and the stereotypes in the minds of jurors by winning aloud some truly deplorable [LAUGHS] lyrics from a very violent rap song.

PROF. CHARIS KUBRIN: Absolutely. And Erik Nielson and I, in our op-ed, discuss one study by Stuart Fischoff that shows how prejudicial and biased perceptions of rap music, in addition to who makes the music, and here we’re talking about young, mostly minority men, right, from low socio-economic status, how all of that sort of combines to create perceptions that this individual is dangerous. And there’s other research that has shown that when violent lyrics are identified as rap music, compared to, say, country music, they're seen as more threatening and more problematic, and individuals are seen as more blameworthy and culpable than when it's attributed to another form of music.

BOB GARFIELD: How did you get into this particular sub-line of legal scholarship?

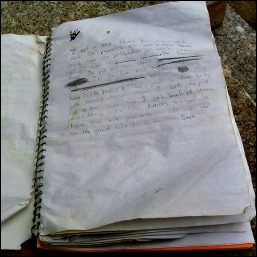

PROF. CHARIS KUBRIN: Well, I was contacted back in 2011 by a lawyer who had come across one of my studied that did a content analysis of gangster rap songs, asking if I would be interested in reviewing the facts of a case involving Olutosin Oduwole, who was an aspiring rapper that was being charged with making a terroristic threat. And basically, what happened was in 2007 Oduwole’s car ran out of gas, leading him to abandon it on the Edwardsville campus of Southern Illinois University, where he was a student. And when the school authorities found his car, among the many items they retrieved was this piece of paper that was crumpled and lodged between the seats. And on one side of the piece of paper were some scribbled rap lyrics, not surprising because he was an aspiring rapper, that everybody agreed were rap lyrics, including the state, And, on the other side, were some rap lyrics, as well, followed by six lines of text at the bottom of the paper, which the state claimed represented a threat, and Tosin, which is his stage name, and his lawyers argue represented the beginning stages of a rap song.

BOB GARFIELD: These lines of text were not benign.

PROF. CHARIS KUBRIN: They were not benign.

BOB GARFIELD: And it’s, it’s not surprising that the police were alarmed. Can you tell me what they said?

PROF. CHARIS KUBRIN: Yes. The six lines of text read something along the lines of, send two dollars to a PayPal account and if this account doesn't reach $500,000 then a murderous rampage, similar to the VT shooting, will occur at another university, followed by, this is not a joke. And, for obvious reasons, they did a search of the apartment, found more notebooks filled with lyrics. Then he was charged with making terroristic threats.

So I was called in to review these notebooks and reviewed hundreds of pages of Oduwale’s lyrics and came to the conclusion, in the context of all of the evidence, that there was a strong possibility that these were the beginnings of rap lyrics, for a number of reasons. I explained that one of the very things we know about gangster rappers is they use this genre convention called an intro and an outro, and these are often non-rhyming words that set up the rap that’s about to occur. And one of the things I discovered reviewing his lyrics is that Tosin liked to use intros and outros a lot in his raps. And so, I argued that this may be an example of an intro or an outro because one of the issues was, well, this doesn’t rhyme, therefore, it can't be a rap lyric.

BOB GARFIELD: What did the jury conclude, that Tosin was an aspiring rapper or that he was an aspiring extortionist and mass murderer?

PROF. CHARIS KUBRIN: They found him guilty.

BOB GARFIELD: Now, it is entirely possible some of the criminal defendants on whose behalf you have testified really are bad actors –

PROF. CHARIS KUBRIN: Mm-hmm –

BOB GARFIELD: - and they really did do the crimes of which they were accused. But it’s one thing to have done something and another thing to have it proven in a court of law.

PROF. CHARIS KUBRIN: Mm-hmm. [AFFIRMATIVE]

BOB GARFIELD: Just to be clear here, you don't even want the actually guilty to be convicted based on irrelevant evidence.

PROF. CHARIS KUBRIN: Exactly. The point is if these guys have done this, you need to find proper traditional evidence to prove that in a court. You cannot have highly prejudicial evidence which is not central to the case, which is irrelevant to the case as the defining factor of the case, which leads this individual to be found guilty. And rap music, no matter how violent the imagery or how misogynistic the views expressed or how offensive you find it, is constitutionally protected speech which has First Amendment protections and should not be used in courts.

BOB GARFIELD: Charis, thank you very much.

PROF. CHARIS KUBRIN: Thank you very much.

BOB GARFIELD: Charis E. Kubrin is an associate professor of criminology, law and society at the University of California, Irvine.