Putting Care Back in the ICU

( Human for Gordan & Betty Moore Foundation / Johns Hopkins Medicine )

MARY HARRIS: So where are we?

CINDY DWYER: So, we’re entering the SICU at Johns Hopkins Hospital on Ziad 9 East.

MH: “SICU” is one of those hospital acronyms that makes a weird kind of sense. Because the “Surgical Intensive Care Unit” — the SICU — is the place you end up if you’re really really sick. Like if you just had a liver transplant, or heart surgery. A few months ago I visited Johns Hopkins in Baltimore, and all 12 beds in the SICU were full.

CINDY DWYER: As we go down the hallway you can see we have some dedicated isolation rooms.

MH: This is Cindy Dwyer — our guide to this place. She’s a senior nurse. And she’s been here 26 years.

CINDY DWYER: Now our patients are very sick. Most of our patients are intubated, on breathing machines and a lot of other type of medical equipment in use and yet it still is a little deceptively quiet.

MH: Obviously something pretty bad has to happen for you to end up in the SICU. But it’s also dangerous just being here. The amazing machines and life-saving procedures…. can hurt or even kill you. Completely by accident.

So, ventilators … which keep you breathing… can also give you pneumonia. The physical act of lying motionless in a hospital bed — can give you a deadly blood clot.

And something called a “central line” — an IV into a vein in your neck, chest, or groin. It lets doctors give drugs and draw blood without sticking you with a needle all the time. But it’s also a great way to get an infection.

And if the ICU doesn’t kill you, it might drive you crazy. A third of ICU patients wind up experiencing delirium. But the people who run this unit — including Cindy — are doing an experiment to try to change the odds.

I’m Mary Harris, and this is Only Human. Today, being a human... in the hospital. And making hospitals... more humane. Because like it or not, when our bodies really fail us, this is where we end up.

There’s one guy behind most of the research Johns Hopkins is doing on patient safety: Dr. Peter Pronovost. Chances are you’ve never heard of him. But you might know him as the “checklist guy.” He’s famous for reducing hospital infection rates by creating simple checklists for doctors and nurses.

DR. PRONOVOST: My mom would say to me, this is the research you do? You make checklists, right? And the public almost incredulously saying like, really, that’s like your innovation?

MH: His research was a major innovation. He started with those “central lines” I mentioned a minute ago, the ones that let doctors administer drugs and draw blood more easily.

They can be threaded inside you for weeks or even months at a time. Pronovost found that having doctors take five simple precautions before inserting the tubes — like washing their hands, or draping the patient in a sterile sheet — brought the infections associated with them down to almost zero.

DR. PRONOVOST: These blood streams infections used to kill as many people as breast or prostate cancer so it's not a trivial little issue, it's a major public health issue.

MH: It seemed almost magical in its simplicity and effectiveness. New Yorker writer Atul Gawande wrote an article about Pronovost’s work, and then, a book.

And now that Pronovost has seen how powerful checklists can be, he wants to put them in place for… everything.

DR. PRONOVOST: We said we want to evolve from eliminating one harm like blood stream infections to eliminating all harms, right? A bold thing but patients don't care if you eliminate one and they're harmed from something else.

MH: You heard him right — he wants to eliminate all harms. So anything that could go wrong while you’re in the hospital... his goal is to eliminate it. It all starts on rounds, the daily check-ins on each patient.

Twice a day in the SICU, Dr. Adam Sapirstein and his team huddle outside each patient’s room. Sapirstein is what’s called an “intensivist” — an expert in critical care.

DR. SAPIRSTEIN: So Jordan, are you going to be able to present?

MH: That’s him, talking to one of the three residents who are here with him. They’re pushing computers on carts, so they can click through each patient’s medical records while they talk.

Jordan Talley, one of the residents, lays out why the patient in room 44 is here, in the SICU.

JORDAN TALLEY: alright so, 49 year old gentleman, he’s status post thoracic aortic aneurysm repair and partial heart bypass performed on July 24th 2015…

MH: The patient, Bruce Meeks, came here after an artery in his chest swelled so much it had to be repaired. Then his kidneys failed, and he needed bowel surgery. He’s on a ventilator. He’s being fed through a tube. And he’s on powerful antibiotics to fight off an infection. Every day is dicey.

DR. SAPIRSTEIN: So any issues, any issues?

MH: The nurse pipes up.

NURSE: Mentally he’s in a really great place the past two days. He’s able to communicate with us a little bit better. He’s sitting up on his laptop. And I think he’s slowly improving.

DR. SAPIRSTEIN: Great, so we’ll go through the Emerge Platform now and then we’ll do the goal sheet.

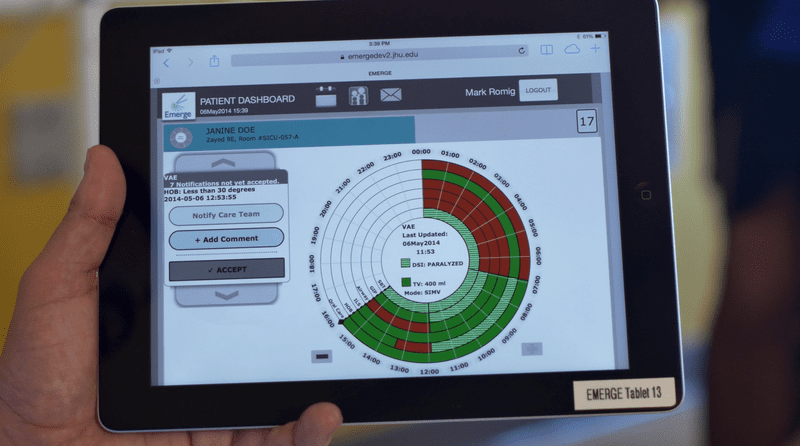

MH: This Emerge Platform Dr. Sapirstein is talking about lives on an iPad, and it’s what makes rounds here really different. Sapirstein is looking at a screen with what looks to be a pie chart on it. He’s flipping through it with a project volunteer.

This tablet takes all the information that’s tracked in a bunch of separate spreadsheets and automatically runs it through all the safety checklists Johns Hopkins has become famous for.

DR. MOHAN: the patient has had a left subclavian line for 35 days, we agreed that that was okay--

MH: Each slice of pie in the pie chart represents something that could go wrong. Right now, it’s alerting the doctors that the patient has had one of those central lines for over a month. The longer that line is in, the higher the risk of infection. The team talks it through, agrees that it’s still safe, and moves on.

DR. SAPIRSTEIN: So why, why is he red here on the weakness scale?

MH: Weakness is another slice of pie. It’s tracking whether patients have been mobile, which fends off weakness. This patient is supposed to get out of bed and stand up for one minute today, which in his state, would be a big accomplishment. He hasn’t done it yet.

DR. MOHAN: The goal was set but no one has reached the goal yet.

MH: The system is really simple — and it saves a lot of time. Without this tablet, the doctors and nurses would have to walk through separate checklists to prevent blood clots and infections. They’d check for signs of delirium. All of which is so time-consuming and complicated that some detail is almost guaranteed to be missed. With this new system, it’s all done automatically.

CINDY DWYER: So everybody who might take care of the patient is going to look at this same visual screen.

MH: Nurse Cindy Dwyer gave me a closer look at how it works. She pointed out that it isn’t just the doctors who can put information into this tablet. Patients and families can, too.

CINDY DWYER: So you know the patient profile these are the types of questions that we ask, things you might like to know about me, it’s a very open ended question, they can put in anything they want.

MH: This might be the most unique innovation. Patients and their families can set their own goals for recovery, and tell the medical team how they’re feeling about their care, or what they’re afraid of. Bruce Meeks’ wife, Diana, let doctors know that her husband likes country music, and wants to get back to things like cutting grass and driving trucks.

Because when this hospital says it wants to prevent “all harms” they mean more than just the physical stuff. One of those slices of pie represents “disrespect of a patient.” Another slice is called “mismatch of goals.” That’s when what the doctors are doing doesn’t match up with what the patient actually wants.

CINDY DWYER: We had a patient that’s family was using this portal that had put in that they had planned to go to Disney.

MH: Not many of us tell our doctors our vacation schedule. In this case, the doctors were able to sit down with the family and say: that trip might not be able to happen when you want it to.

CINDY DWYER: Just knowing that piece of information kinda let us start that dialogue, which to some people those family plans are just as important as how long your central line has been in. So it’s nice to have that live somewhere where everybody, everybody can see it.

MH: In fact this whole project hinges on doctors and nurses putting patients first. Think about what checklists do: they catch mistakes. In a system that revolves around checklists, everyone caring for a patient has to learn to be okay with being corrected.

They have to learn not to take it personally. Because catching mistakes isn’t about making a doctor or a nurse look bad, or punishing them. It’s about keeping a patient — a person — from getting hurt. Cindy says the shift has been huge.

CINDY DWYER: We’re actually much more empowered to point out things that aren’t safe or that even potentially aren’t safe . We now track near misses as opposed to phew we got along with that one! luckily that didn’t happen!

MH: But that must be hard too! When you have a near miss you want to forget about it, and be like oh, it was a near miss!

CINDY DWYER: You do, but we’ve really trained and empowered our staff that those are just as important. You know, our reporting process isn’t punitive at all. It’s like we want you to feel comfortable and feel empowered to report these things, so that we can track them.

MH: Coming up: why a hospital that keeps its doctors and nurses humble might be a safer one.

DR. PRONOVOST: The doctors said “Peter, you can’t have a nurse question us in public, it hurts our credibility it looks like we don’t know something,” to which I said “Okay, welcome to the human race, we all don’t know something.”

MH: And we find out whether all those pie charts and checklists are actually making a difference.

--

MH: Thanks for listening to this week’s episode of Only Human.

If you like what you’re hearing, check us out on Facebook — search for Only Human podcast. Keep up with what’s happening on the show.

A listener who calls herself Sarah E. got in touch after hearing last week’s interview with Bishop Gwendolyn Phillips Coates, about helping people think through how they want to die.

“My dad just passed away 2 weeks ago,” she said. “I was so glad I knew his wishes in advance. I want everyone to listen to this episode and have these conversations. They'll be so thankful later on that they did.”

We love hearing your feedback, so please keep it coming. And thanks!

--

MH: I’m Mary Harris, and this is Only Human. After visiting the Surgical ICU at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore, I wanted to talk to to the checklist guy again — Peter Pronovost. I had few questions for him. Starting with: if the goal is making an ICU as safe as it can be, why spend so much time on softer things, like knowing a patient’s vacation plans?

So I walked across the campus to his office, where he was getting ready for a big meeting. And I asked him. He gave me a two-part answer. First, it’s just important, hospitals should treat people well. Period. But also: he believes treating patients humanely helps them get better.

DR. PRONOVOST: What we see is that when patients are more engaged in their care and they’re more respected, they heal faster, they have better outcomes and ironically the clinicians are happier.

MH: You’re making it sound obvious that it would improve things, but is it?

DR. PRONOVOST: You know, the structures that make us make safe decisions are the same ones that allow us to treat each other respectfully and the same ones that allow us to have empathy for our patients. It’s interesting that you say that, because as our work has evolved, we used to see focus on safety, focus on staff engagement, and focus on patient experience, as three different groups, and as we were students of this, what we’ve seen is it all fundamentally boils down to the same thing and that is, this empathic care, where we’re humble and curious and where we respect each other and where we’re accountable.

MH: Okay, so if we accept that an empathetic place is also a safer place, how do we get there? Pronovost says you have to change something fundamental to how hospitals have historically functioned: you have to be able to question the authority of doctors. I wanted to know: how hard is it to overhaul the hierarchy of a hospital?

DR. PRONOVOST: I’ll share with you a story. When we first were trying to get some of this culture work done. I started saying okay we’re going to invite patients on rounds and we want to make sure the nurse is present on rounds because they have valuable input, and if the nurse isn’t available we’ll go to a different room and come back.

MH: So picture this. Instead of having doctors huddle outside of a patient’s room relying on written reports by the nurses, they’d now go out of their way to make sure the nurse and the patient or the patient’s family were able to be there. And that might mean the doctors wouldn’t do rounds in the orderly way they were used to.

DR. PRONOVOST: And you would have thought that it is written in the Bible that you must go in order room 1,2,3, 4 and 5 because when I said you know it’s okay, we can like walk the 10 feet down to room five and then come back, it was this, you could see people cringing.

MH: Pronovost calls changes like this “small acts of creative transgression.” They’re part of his attempt to change the culture of the hospital one step at a time.

DR. PRONOVOST: It tapped into an innate need that every one of our doctors and nurses were feeling. And matter of fact, uniformly you could kind of see people perk up and it’s rewarding for them and and it’s rewarding for patients.

MH: But is it working? A year and a half into the project, clinicians in the SICU have used it to care for thousands of patients. Johns Hopkins can’t say for sure, yet, that this system is better. But key markers ARE moving in the right direction. Delirium and blood clot rates have gone down. There are more meetings, now, between doctors, patients and family members to make sure everyone is on the same page.

And there are plans to expand the program. An intensive care unit at the University of California’s Medical Center in San Francisco has started using it. And Johns Hopkins is partnering with Microsoft to start pilot programs around the country next year.

Back in the SICU, Dr. Sapirstein is nearing the end of his shift. He’s the first to admit -- they still don’t know if this system will work, at Johns Hopkins or anywhere else. But he believes in the goal of engineering better care.

DR. SAPIRSTEIN: Everybody wants to have Peter Pronovost be their intensivist. But the quality of your care shouldn’t be dependent on exceptional human performance.

MH: He says, you have to make exceptional care part of the system. Early on in planning this project, a colleague said to Dr. Sapirstein, “I get why you’re trying to bring infections down and reduce blood clots. But why red flag something as abstract as ‘mismatch of goals’?” Dr. Sapirstein said this:

DR. SAPIRSTEIN: We are really really good at preventing people from dying in the ICU. And often times patients and family members know that what someone really wanted was to be cured and to have a normal life and they never wanted to be preserved in an ICU without the hope of having that.

MH: Suddenly, I realized we were having a conversation about how we die. And that might be one of the most interesting side effects of this project. Re-engineering the ICU to make the patient's point of view central leads to an existential place. At a hospital like this, it’s easy to throw a lot at a patient — keeping them alive with machines and surgeries. Until one of those slices in the pie chart glows red. Suddenly these doctors find themselves asking: is this actually what the patient wants?

As for that patient we heard about at the beginning of the episode ... Bruce Meeks… he spent more than four months in the intensive care unit. He was released to a regular hospital floor just this month. And last week, something really special happened. This is his daughter, Tiffany.

TIFFANY MEEKS: I had a white gown on and I had my bouquet of flowers, dad held my left hand, and we walked down the aisle together. Well, of course he was in a wheelchair.

MH: Meeks got to see his daughter… get married. The wedding was planned for next Fall, but Tiffany decided they shouldn’t wait. The ceremony was at the hospital chapel. The staff arranged for violins, a choir, flowers and a wedding cake. There were silver bows on the seats, and a reception after.

TIFFANY MEEKS: Every girl wants their dad to walk them down the aisle and at one point in time I didn’t think that it was going to happen and it happened.

MH: Another thing she wasn’t sure she’d see — her dad leaving the hospital. Johns Hopkins plans to send him to a rehab facility soon — bringing him one step closer to going home.

--

We want to know about your experiences with hospitals — as a patient or a family member. Have you worried about things like infections and medical mistakes? Did you feel like doctors were treating a whole person — or an illness? And what about just being in the hospital got under your skin?

Share your story with us and we might use it in a future show. Send an email to onlyhuman@wnyc.org, or find us on Facebook.

Only Human is a production of WNYC Studios. This episode was produced by Paige Cowett and edited by Molly Messick. Our team includes Amanda Aronczyk, Elaine Chen, Kenny Malone, Fred Mogul and Kathryn Tam. Our technical director is Michael Raphael. Our executive producer is Leital Molad. Jim Schachter is the Vice President for news at WNYC.

Special thanks this week to Winn Periyasamy and Lena Walker. You guys have been such great help over the last few months, and we’re sorry to see you go. I’m Mary Harris. Talk to you next week.