The Power of Police Unions

[music]

David Remnick: We always associate the holidays with certain ideas about going home, going home to visit the family or seeing childhood friends. A Syrian artist named Mohamed Hafez has been living in the United States and he's mourning the loss of his home in Damascus to the destruction of the Syrian war. For several years, he has created lifelike miniatures of buildings in Syria. Tiny, intricate tableaus of the homeland he cannot return to and they're incredible to see. His work is the subject of A Broken House, a documentary short presented by New Yorker Studios.

Mohamed Hafez: It's hard to pin down when exactly the war started. My parents hesitated to leave home. It's not until the clashes broke off 100m away and shook our whole house. They realized, "Okay, the conflict is now on our doorstep and we need to leave." They came and lived in my small apartment. I was a very young designer pitching 200, 300, $400 million buildings. I had to keep a straight face at work and still perform, but I was very troubled, extremely troubled. I had o monitor literally on news channels 10-hours a day, I'm working and I'm seeing the Arab world blow up.

David Remnick: Mohamed Hafez in A Broken House. The film was directed by Jimmy Goldblum and it's been shortlisted for an academy award along with five other New Yorker films. You can watch A Broken House at newyorker.com.

[music]

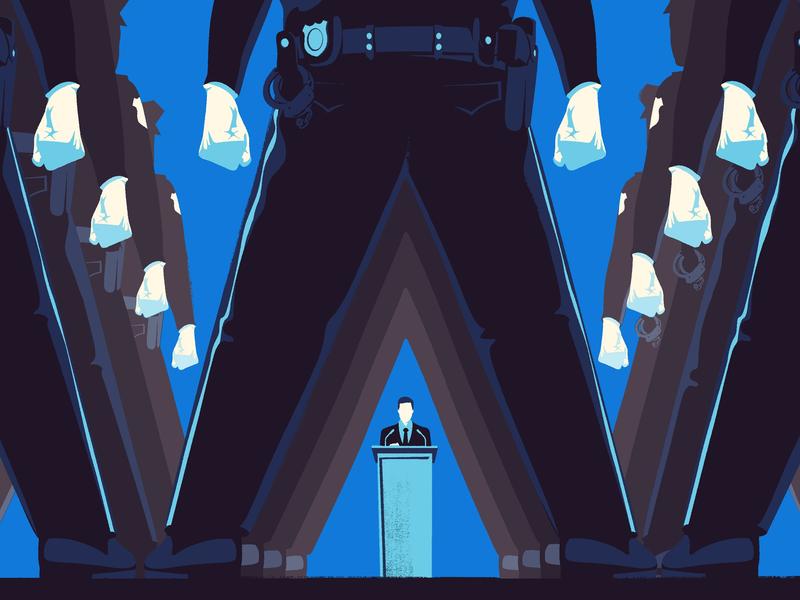

David Remnick: Now, after the intense energy that was focused on policing during and after the 2020 protests, the movement for change appeared to stall during the 2021 elections. In Minneapolis where the defund movement took off after the murder of George Floyd voters then rejected a measure to dismantle the local police department. Here in New York City, Democrats turned away from the more progressive candidates and instead chose Eric Adams. Adams is a former police officer who was once active in reforming the department but in his campaign, he spoke to voters in the familiar language of law and order.

Adams has certainly thought hard and long about the example of his predecessor Bill de Blasio. De Blasio ran for office in the first place promising an aggressive agenda of police reform but after a backlash from the police de Blasio became far more deferential. His administration expanded the use of a state law that shielded police disciplinary records, a law known as 50-a.

Then he celebrated when 50-a was then repealed. By the end, de Blasio was openly hated by his own police force and at the same time proved a great disappointment to its critics. Longtime staff writer, Bill Finnegan, reported for us in 2020 on exactly how the police are able to exert so much influence over local politics. Here's Bill.

Bill Finnegan: We've seen a lot of cases of progressive politicians promising big changes in policing and then not delivering them. To understand how that happens, I think we have to go back to the 2014 killing of Eric Garner on Staten Island, and a warning. You'll hear some disturbing tape.

Eric Garner: "For what? I didn't sell anything."

Bill Finnegan: Eric Garner was a Black man, 43-years old, six kids, allegedly selling loose cigarettes on the street. When he was approached by police officers he denied doing anything wrong, shied away.

Eric Garner: "I'm minding my business. Please just leave me alone. I told you the last time, please just leave me alone."

Bill Finnegan: The officers were determined to arrest him and tackled him. Officer named Daniel Pantaleo put him in a chokehold, got him on the ground. He cried out. There's a videotape his friend took of this whole thing. 11 times he cried out, "I can't breathe." They took their time handcuffing him and within the hour he was dead. His death was ruled a homicide by the medical examiner.

Woman: On camera, these cops committed a chokehold. Despite it being on camera, they still refuse to indict the murderer's act.

[protesters chanting]

Bill Finnegan: The killing of Eric Garner became a national story, the focus of a lot of protests. It got much more intense when a grand jury on Staten Island declined to indict Daniel Pantaleo for the killing.

Journalist: Two days after a New York City grand jury cleared a white police officer in the chokehold death of an unarmed Black man, the protests are growing larger and spreading across the country.

Bill Finnegan: People were really angry after that. The Garner family seeking justice and all their supporters versus the police. In that situation, Mayor de Blasio expressed sympathy for the Garner family and he told a story about his son Dante who's biracial.

Mayor de Blasio: Chirlane and I have had to talk to Dante for years, about the dangers he may face. A good young man, a law-abiding young man, who would never think to do anything wrong, and yet, because of a history that still hangs over us, the dangers he may face. We've had to literally train him, as families have all over this city for decades, in how to take special care in any encounter he has with the police officers who are there to protect him.

Bill Finnegan: This story which to many people just sounds like common sense, a sad fact the conversation that most Black families need to have with their kids in America was really unpopular with the police. The people who speak for the rank and file tend to be the union leaders. They're five unions and the biggest is the Police Benevolent Association, represents the rank and file, 24,000 members. The president is Patrick Lynch.

Patrick Lynch: What police officers felt yesterday after that press conference is that they were thrown under the bus. He needs to support New York City police officers. He needs to say that teach our children, every last one of our children, our sons and daughters to respect police officers. You cannot resist arrest because resisting arrest leads to confrontation. Confrontation leads to tragedy. That's the support we need.

Bill Finnegan: Shortly after this very uncomfortable confrontation, a guy with a long criminal record came to New York and saying that he was avenging Eric Garner killed two police officers and then killed himself. That day really poisoned the relationship between de Blasio and the police unions.

Journalist: A shocking moment. As New York Mayor, Bill de Blasio, entered the hospital Saturday where the mortally injured officers were taken, fellow police turned their backs on him, a powerful and divisive message to the mayor of this major city who has lost their trust.

Patrick Lynch: There's blood on many hands tonight. Those that incited violence on the street under the guise of protests that tried to tear down what New York City police officers did every day. We tried to warn it must not go on, it cannot be tolerated. That blood on the hands starts on the steps of city hall in the office of the mayor.

Bill Finnegan: These events, this humiliation really seemed to break de Blasio. That was when he felt the hatred and power of the police unions. His reformist spirit when it came to criminal justice and the police seemed to wane. When it came to section 50-a that secrecy statute in New York state that prevented the public from viewing officer disciplinary records, de Blasio continued to pay lip service to wanting change, but he really never did anything. Michael Sisitzky works on a police transparency and accountability project at the New York Civil Liberties Union.

Michael Sisitzky: After Daniel Pantaleo killed Eric Garner, request went into the Civilian Complaint Review Board to produce a summary of any prior substantiated complaints that had been lodged against that officer. The administration refused to release those records, cited 50-a to block the release and that was a decision that ultimately was upheld in the courts.

Woman: Now I'm going to bring up Gwen Carr, the mother of Eric Garner.

Gwen Carr: My son was murdered on New York Streets in Staten Island. The de Blasio administration, they blocked everything we tried to do, tried to get records exposed. I'm just here today to say, when this is not going away, we are here and we are going to be here and we are going to see that justice is served correctly.

Bill Finnegan: Even beyond the Garner case, the de Blasio administration continued to ramp up enforcement of 50-a.

Michael Sisitzky: The NYPD ceased a 40-year practice of publicizing records from NYPD disciplinary proceedings. They used to put the outcomes of those cases on a clipboard at one police plaza, where you could see which officers were promoted, which officers were disciplined and that was available to the public, to members of the press to know what those outcomes were. In 2016, the de Blasio administration made a deliberate decision to take down that clipboard, claiming that for 40 years, unbeknownst to anyone else, the city had been violating 50-a.

Bill Finnegan: Now it's hard to say why exactly Bill de Blasio and his administration became so much more sympathetic to the police. When it came to 50-a, the unions were very vocal about the fact that they did not want these records released, and traditionally the police unions get what they want in New York State and New York City.

Kirk Burkhalter comes from a real police family. His father and his brother were cops. He joined the force at 21. He was a member of a series of unions as he got promoted. First, the PBA, when he was a patrolman on up to the Detective's Endowment Association, where he was a union delegate before he retired. He's now a law professor at New York law school.

Kirk Burkhalter: What's important to remember is that the police unions represent their membership. They do not represent the public. They are not in a position, arguably, nor should they be in a position to lobby, one way or another, for reform. They certainly lobby on behalf of their members. I think where the rubber meets the road is this discussion of what is good for the membership is that also good for the public? That's where the debate really lies.

Bill Finnegan: Being a public sector union, it's different. Private sector unions are negotiating. It's basically, workers versus management. Those are the two parties. Whereas public sector unions are more like there's a government and there's the membership, again, the workers, but you have this invisible third party, as I think of it, the public, what's the public interest here?

Kirk Burkhalter: That has to be taken into account, cannot be so myopic as to just say, "Hey, I have this job and it's all about me and it's not about anybody else." There is this third party there. Now, does that mean all unions are averse to the public? I can see how the public might have that perception, but at the end of the day, and this sounds like a radical concept, but we serve the public, the public being the person that the police arrest as much as the victim. They're all the public and they all have rights.

Bill Finnegan: In the Garner case, we saw the unions, the PBA in particular come out and defend their member even contradicting the medical examiner about cause of death and whether he applied a chokehold. They circled the wagons around Pantaleo and defied the public call for justice.

Patrick Lynch: It was not a chokehold. He was a big man that had to be brought to the ground to be placed under arrest by shorter police officers. Sometimes the use of force is necessary, but it's never pretty to watch.

Bill Finnegan: Although Eric Garner was killed in 2014, the story just goes on and on. The NYPD took five years before it finally fired Daniel Pantaleo. This sense of impunity that the police seem to feel and express through their unions is just kind of shocking.

Kirk Burkhalter: What makes police unions different from many other unions? They are the first line of support for our elected officials, no politician on the local or state level is going to get re-elected again if crime goes up, we see it all the time. You can imagine just one day in New York City, imagine one day if the police took off. It'd be similar to the movie the Purge, just complete anarchy. I believe this is an extreme source of power for police unions. Elected officials need them.

Now, there are laws against the police union striking, but that doesn't necessarily affect the ability for police unions to conduct some form of job action such as slowing down, and that absolutely could result in a rise in crime and a lack of safety for the general public. Politicians need the unions very, very much, and that is their source of power.

Patrick Lynch: Over the last number of years since this Mayor walked into city hall, I've stood at this podium and said, his decisions will have a chilling effect on New York City police officers. While the criminal advocates have gotten what they want, the police department is frozen. The police department can't stop the killers. They can't stop the criminals. They can't effectively do their jobs.

Bill Finnegan: The language of anarchy, that fear-mongering about what will happen if we don't do our jobs, these unions have often used it in argument and in contract negotiations with mayors, and for that matter with police chiefs. You always need to keep that distinction in mind between the police unions and the police department. Police unions can be a police chief's worst nightmare.

Now, activists, people working to make policing less abusive, more accountable, go up against police union power and have no illusions about it. Joo-Hyun Kang is the director of Communities United for Police Reform.

Joo-Hyun Kang: Yes, I think that there's a difference between blocking reform in terms of swaying the public versus blocking reforms in terms of having elected officials be afraid to pass important reforms, and too many elected officials, it really doesn't matter what party they belong to. Too many elected officials are scared of the power of police unions. They're are scared of being leafleted when they run for election or re-election. They're scared of being lambasted by the police unions.

We're in a period right now, I think in the country, not only in New York City, where many members of the public and more than what the police unions would make it seem, want to see fairness, and they don't want to see people brutalized by the police and they don't want to know that this is happening to themselves or their families or their neighbors.

[protests]

Bill Finnegan: Everything changed around these issues in many places and including New York after the killing of George Floyd and the enormous protests at the end of May, into early June Black Lives Matter really on the march. In Albany, what that meant was that this repeal of 50-a, that movement which had been getting nowhere. The act had not even been voted out of committee, suddenly moved, and along with other police reform, new ban on chokeholds. Governor Cuomo said, "Whatever you send me I'll sign," and they sent him a lot and he signed it and 50-a was repealed.

Governor Cuomo: Morning, everyone. We have Gwen Carr with us, who is the mother of Eric Garner. We have Valerie-- The New York state legislature has quickly passed the most aggressive reforms in the nation. I'm going to sign those bills in a moment.

Bill Finnegan: It was as if the police unions were just blindsided, suddenly they weren't there telling their legislators what to do.

Joo-Hyun Kang: The police unions aren't done and they certainly intend to continue fighting and trying to roll back even this repeal. I think that what we saw in June was that maybe they were somewhat caught off guard, but they were certainly still lobbying to try to make sure that it wasn't a repeal. I think the difference was that in spite of their huge megaphone, people power and organizing actually won.

We heard people across the state in New York City at rallies chanting repeal 50-a which is kind of a dorky chant but was our hashtag for many years, it was a dorky hashtag. Is a dorky chant, but it really says something when you have something so in the weeds capture the imagination and the understanding of large sectors of the public.

Bill Finnegan: The police unions, whether they were blindsided or not, were really furious that they didn't have a seat at the table. Michael O'Meara is the head of the Transit Police Union in New York.

Michael O'Meara: I am not Derek Chauvin. They are not him. He killed someone, we didn't. We all restrained. You know what? I'm saying this to all the cops here because you know what? Everybody's trying to shame us. The legislators, the press. Everybody's trying to shame us into being embarrassed about our profession. Well, you know what? Stop treating us like animals and fox, and start treating us with some respect.

Bill Finnegan: Right now there's this real question of whether the tremendous amount of energy around change and reform will even affect the police unions. The unions have always been an arch-conservative force in city politics, but they're not static politically. NYPD is now a majority-minority force. Older white officers are retiring. In my conversations, plenty of people suggested that the union leadership will eventually reflect the membership with more ethnic and perhaps political diversity.

On the other hand, as Kirk Burkhalter points out, the unions see themselves and are the only line of defense for their members in an increasingly hostile political climate. Maybe this is point is kind of trench warfare, statute by statute, and maybe one can only expect so much reform to come from inside the unions themselves.

Kirk Burkhalter: I think it's highly unlikely that the union leadership would lose the support of the rank and file. Imagine as a police officer, when you turn on the television, the only one you see advocating your position, ready to go down in flames for supporting you is the union leadership. Would that ever be someone that you are likely to not support?

[music]

David Remnick: The New Yorker's Bill Finnegan spoke with Kirk Burkhalter, Joo-Hyun Kang, and Michael Sisitzky in our story aired in 2020. In August, New York Governor Cuomo resigned after a series of scandals, and Bill de Blasio ended his term as mayor on Friday. Eric Adams, a former police officer, is New York's 110th mayor. I'm David Remnick. Thanks so much for listening. A happy new year to you, one of health and happiness. See you soon.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.