Piltdown at 100: A Look Back on Science's Biggest Hoax

(

Kevan Davis

/

flickr

)

Transcript

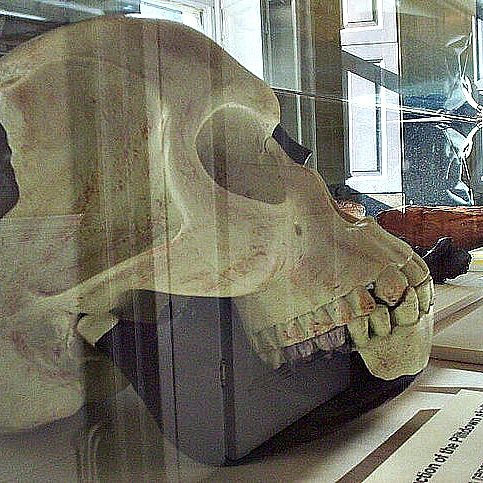

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And now for your delectation, one of our favorite interviews about men messing with biological information. It’s an old case involving a piece of a very old man, garnished with ape. More than a century ago, a skull that looked human and a jaw that looked apeish were presented at a special meeting of the Geological Society in London. The so-called “Piltdown man” became widely accepted as a crucial link in the human evolutionary chain, crucial, that is, until 1953, when the bones were exposed as a total hoax. I spoke to Nova senior science editor Evan Hadingham about this tantalizing example of scientific skullduggery.

EVAN HADINGHAM: Charles Dawson was a well-to-do solicitor who lived in the town of Lewes in Sussex, one of the richest areas in the whole of Britain for geological and archaeological finds. And so, in this town was a thriving group of amateur collectors. They were highly competitive. Dawson had been roaming the downs for decades, and every now and then he'd send some curious discovery to Arthur Smith Woodward, who was a curator at the British Museum of Natural History in London.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And Smith Woodward lent a lot of credibility to the Piltdown discovery, even though scientists suspected that the skull and the mandible actually came from different skeletons.

EVAN HADINGHAM: There was some initial skepticism about the find but every time a serious pointed debate was raised, lo and behold, a piece of fossil would crop up almost miraculously, which answered some of the objections that called the find into question.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But, interestingly, it was foreigners who were more skeptical than the Brits. And this brings us to the political context.

EVAN HADINGHAM: Well, 1912 - it's before the outbreak of the Great War, of course, which shook up the values of all the imperial powers - so it’s still the height of the British Empire. Playing into a sense of national pride was the notion that perhaps England had been the entire center for the origin of humanity. Surely, it was about time that Britain had its own discovery, on par with those that had been found in Germany, with the Neanderthals, and so on; there was probably unconscious racist overtones in that continuing willingness to believe that Piltdown was a true discovery.

In the 1920s, the first discoveries were made of ancestral humans in Southern Africa, and they were very easy to reject because even though Darwin thought that Africa was the probable place of origin for humanity, it was far more comfortable to think of this man ape in England being a formative character in our past, as opposed to a place like Africa.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Since Piltdown was exposed as a hoax in 1953, people have floated theories about who the hoaxer was. Some have implicated Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

EVAN HADINGHAM: The evidence that Conan Doyle had anything to do with this consists mostly [LAUGHS] in parallels in Canon Doyle’s famous tale, “The Lost World,” about a lost colony of ancient humans that coexisted with the dinosaurs on a plateau in South America, in the present day. Conan Doyle did know Dawson. They did lunch together. And Canon Doyle may have chatted to Dawson about his developing idea for this exciting novel, and it’s possible that that actually planted the idea of the hoax in Dawson's mind, not the other way around.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Why did Smith Woodward never begin to doubt Piltdown? Anytime anyone ever found anything, Dawson was always there.

EVAN HADINGHAM: He really charmed Smith Woodward. Smith Woodward also invested a huge amount of his reputation and career in Piltdown. For over 20 years, he dug every summer, rather sadly, never finding anything again. So during Smith Woodward’s lifetime, it was very unlikely that anybody would critically examine the remains. But in 1948, he died.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So that brings us to the late forties and early fifties. A couple of scientists tried to assess the Piltdown remains. What sort of high-tech CSI techniques were available to them at the time?

EVAN HADINGHAM: They ran the relatively newly discovered radiocarbon test, and the shocking truth finally came out. It was a modern jaw of an orangutan and the skull fragments belonged to a modern human, possibly from a medieval cemetery. And once suspicions about the date were raised –

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm –

EVAN HADINGHAM: - they did something really basic, which was to really examine the teeth of the jaw under a magnifying glass.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

And, lo and behold, it was obvious that they’d been filed flat, and that was why they didn't resemble an ape’s tooth. The most obvious piece of the fraud was a canine tooth that was found in 1913, planted by Dawson a year after the first remains. Because you can't stain a tooth the way you can bone, the hoaxer actually used paint on the root of the tooth.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

What looks obvious today wasn’t at all obvious to the specialists back then, because of their expectations.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So in terms of scientific hoaxes, is there anything that compares to Piltdown?

EVAN HADINGHAM: Not really. Piltdown still stands as the preeminent story of scientific skullduggery.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Pun not intended? [LAUGHS]

EVAN HADINGHAM: Sorry. Anyway, it really did have an extraordinary influence on the way we saw human evolution. It fooled the scientific community for four decades, and there’s been nothing like that ever since.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: What drew you so deeply into the Piltdown story?

EVAN HADINGHAM: It's the ultimate Agatha Christie story.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

Charles Dawson had a well-documented and burning ambition to make his mark on the scientific world. People have looked at the other things that Dawson collected, and at the present time I believe the count of fraudulent objects is 38.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

Spanning a couple of decades, Dawson had forged not just bones and stones but Roman statuettes, and there was even a sea monster that he claimed to have seen crossing the English channel.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

All of these things form the picture of a very smart but compulsively dishonest and manipulative collector. We really don't know the fine details of how Dawson did this. You can get completely lost in the search for hints in letters and so on. For anybody who loves Masterpiece mystery –

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

- you can find all of that in the Piltdown story.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Thank you very much.

EVAN HADINGHAM: [LAUGHS] Thanks, Brooke.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Evan Hadingham is senior science editor at WGBH’s Nova and, as far as I can tell, an anatomically modern human.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And now for your delectation, one of our favorite interviews about men messing with biological information. It’s an old case involving a piece of a very old man, garnished with ape. More than a century ago, a skull that looked human and a jaw that looked apeish were presented at a special meeting of the Geological Society in London. The so-called “Piltdown man” became widely accepted as a crucial link in the human evolutionary chain, crucial, that is, until 1953, when the bones were exposed as a total hoax. I spoke to Nova senior science editor Evan Hadingham about this tantalizing example of scientific skullduggery.

EVAN HADINGHAM: Charles Dawson was a well-to-do solicitor who lived in the town of Lewes in Sussex, one of the richest areas in the whole of Britain for geological and archaeological finds. And so, in this town was a thriving group of amateur collectors. They were highly competitive. Dawson had been roaming the downs for decades, and every now and then he'd send some curious discovery to Arthur Smith Woodward, who was a curator at the British Museum of Natural History in London.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And Smith Woodward lent a lot of credibility to the Piltdown discovery, even though scientists suspected that the skull and the mandible actually came from different skeletons.

EVAN HADINGHAM: There was some initial skepticism about the find but every time a serious pointed debate was raised, lo and behold, a piece of fossil would crop up almost miraculously, which answered some of the objections that called the find into question.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: But, interestingly, it was foreigners who were more skeptical than the Brits. And this brings us to the political context.

EVAN HADINGHAM: Well, 1912 - it's before the outbreak of the Great War, of course, which shook up the values of all the imperial powers - so it’s still the height of the British Empire. Playing into a sense of national pride was the notion that perhaps England had been the entire center for the origin of humanity. Surely, it was about time that Britain had its own discovery, on par with those that had been found in Germany, with the Neanderthals, and so on; there was probably unconscious racist overtones in that continuing willingness to believe that Piltdown was a true discovery.

In the 1920s, the first discoveries were made of ancestral humans in Southern Africa, and they were very easy to reject because even though Darwin thought that Africa was the probable place of origin for humanity, it was far more comfortable to think of this man ape in England being a formative character in our past, as opposed to a place like Africa.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Since Piltdown was exposed as a hoax in 1953, people have floated theories about who the hoaxer was. Some have implicated Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

EVAN HADINGHAM: The evidence that Conan Doyle had anything to do with this consists mostly [LAUGHS] in parallels in Canon Doyle’s famous tale, “The Lost World,” about a lost colony of ancient humans that coexisted with the dinosaurs on a plateau in South America, in the present day. Conan Doyle did know Dawson. They did lunch together. And Canon Doyle may have chatted to Dawson about his developing idea for this exciting novel, and it’s possible that that actually planted the idea of the hoax in Dawson's mind, not the other way around.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Why did Smith Woodward never begin to doubt Piltdown? Anytime anyone ever found anything, Dawson was always there.

EVAN HADINGHAM: He really charmed Smith Woodward. Smith Woodward also invested a huge amount of his reputation and career in Piltdown. For over 20 years, he dug every summer, rather sadly, never finding anything again. So during Smith Woodward’s lifetime, it was very unlikely that anybody would critically examine the remains. But in 1948, he died.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So that brings us to the late forties and early fifties. A couple of scientists tried to assess the Piltdown remains. What sort of high-tech CSI techniques were available to them at the time?

EVAN HADINGHAM: They ran the relatively newly discovered radiocarbon test, and the shocking truth finally came out. It was a modern jaw of an orangutan and the skull fragments belonged to a modern human, possibly from a medieval cemetery. And once suspicions about the date were raised –

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm –

EVAN HADINGHAM: - they did something really basic, which was to really examine the teeth of the jaw under a magnifying glass.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

And, lo and behold, it was obvious that they’d been filed flat, and that was why they didn't resemble an ape’s tooth. The most obvious piece of the fraud was a canine tooth that was found in 1913, planted by Dawson a year after the first remains. Because you can't stain a tooth the way you can bone, the hoaxer actually used paint on the root of the tooth.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

What looks obvious today wasn’t at all obvious to the specialists back then, because of their expectations.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So in terms of scientific hoaxes, is there anything that compares to Piltdown?

EVAN HADINGHAM: Not really. Piltdown still stands as the preeminent story of scientific skullduggery.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Pun not intended? [LAUGHS]

EVAN HADINGHAM: Sorry. Anyway, it really did have an extraordinary influence on the way we saw human evolution. It fooled the scientific community for four decades, and there’s been nothing like that ever since.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: What drew you so deeply into the Piltdown story?

EVAN HADINGHAM: It's the ultimate Agatha Christie story.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

Charles Dawson had a well-documented and burning ambition to make his mark on the scientific world. People have looked at the other things that Dawson collected, and at the present time I believe the count of fraudulent objects is 38.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

Spanning a couple of decades, Dawson had forged not just bones and stones but Roman statuettes, and there was even a sea monster that he claimed to have seen crossing the English channel.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

All of these things form the picture of a very smart but compulsively dishonest and manipulative collector. We really don't know the fine details of how Dawson did this. You can get completely lost in the search for hints in letters and so on. For anybody who loves Masterpiece mystery –

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

- you can find all of that in the Piltdown story.

[MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Thank you very much.

EVAN HADINGHAM: [LAUGHS] Thanks, Brooke.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Evan Hadingham is senior science editor at WGBH’s Nova and, as far as I can tell, an anatomically modern human.

Hosted by Brooke Gladstone

Produced by WNYC Studios