The People Who Make Death Their Life's Work

( St. Martin's Press )

Melissa Harris-Perry: Thanks for sticking with us on The Takeaway. I'm Melissa Harris-Perry. Death is the only certainty we all share, but for many, death remains a challenging topic, not just for polite conversation, but even in our own inner musings. Think about this, even during our recent collective experience of the pandemic, which brought so much death, we often turned our attention to life, asking how we could be safe, cheering for healthcare workers saving lives, and celebrating those who survived the ravages of COVID before there was a vaccine or effective treatment.

It makes sense, this enthusiasm for life, but given that death is our certain eventual outcome, there is, perhaps, also value in pausing long enough to ask who does the work of death and should we also acknowledge and perhaps even celebrate those who labor with the dead?

Hayley Campbell: My name is Hayley Campbell. I'm a freelance journalist in London and I'm the host of the Must Watch podcast on the BBC.

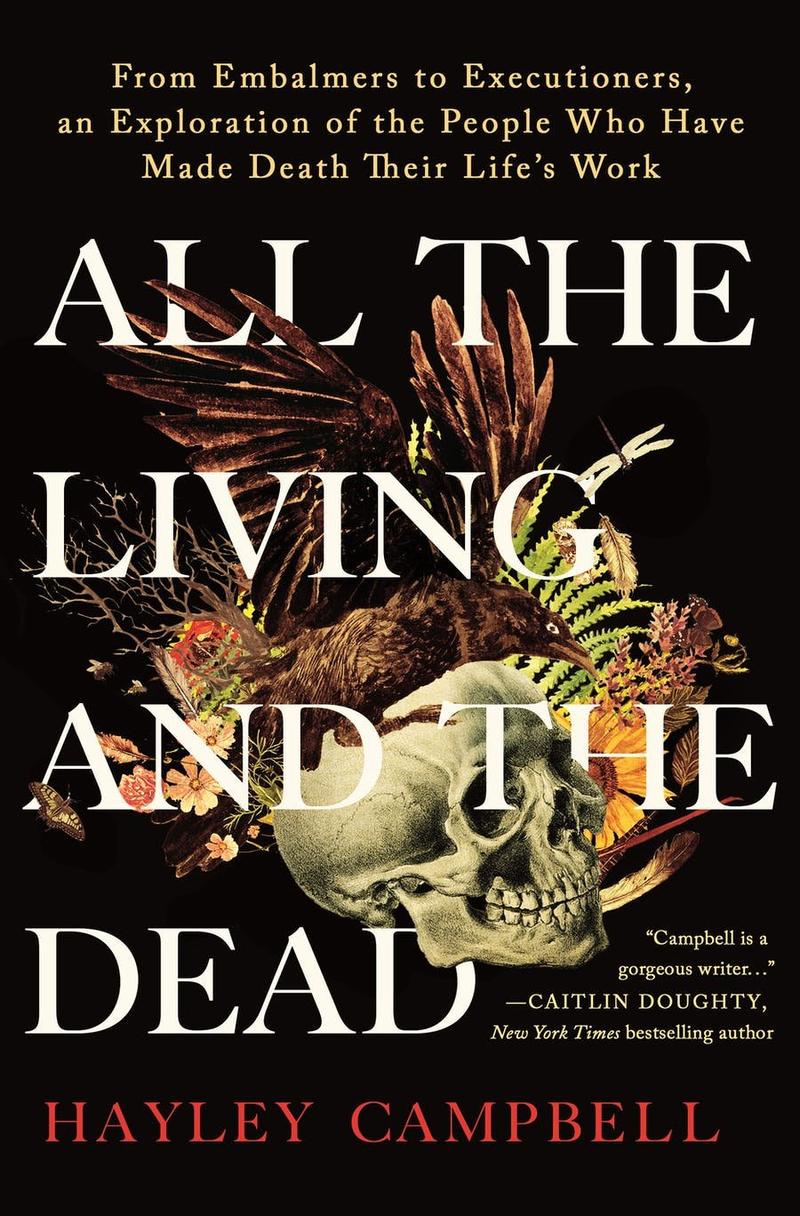

Melissa Harris-Perry: Hayley is the author of a new book, All the Living and the Dead. It looks at those who have devoted their lives to the dead, the people who tend our bereavements, our burials, and our bodies, and whose work is too often unseen. Hayley has been fascinated by this since her childhood. Her father illustrated graphic novels, some of which contained graphic details.

Hayley Campbell: We had pictures of autopsy reports and crime scenes that he was using as reference pictures and I didn't think that these were unusual things to have around the house.

Melissa Harris-Perry: When Hayley was 12, a friend of hers died. It forced her to confront not only what death looks like, but also what it doesn't look like, the parts of it that we rarely see, but that someone somewhere has to.

Hayley Campbell: Sitting there in that church, staring at my friend's white coffin, I knew that other people had pulled her from the water, dried her, carried her there. Other people had cared for her where we could not.

Melissa Harris-Perry: I spoke with Hayley about her book and the people in it, both the living and the dead.

Hayley Campbell: Because I've been fascinated with death, I've always wanted to know what happens exactly to a body once it becomes a dead body and who looks after it. Again, it's one of those things that is secret, and as a journalist, I'm quite a nosy person. My favorite thing is to go to museums and ask a curator, "What have you got in the back room that you can't fit out here and can I see it?"

This was sort of me doing that again because I think there is this whole group of people who are hidden to us, and what they do is so important in terms of the management, not only of the dead, but also of our feelings. They do so much that they never tell us about. Each person I interviewed, there was some small little detail that they barely mentioned to me and I had to go, "Wait, tell me that again."

One funeral director told me about the fact that when people come, when they bring the bag of clothes that they want their family member to be buried in, they always forget the underwear, and so he has a collection of underwear and socks in different sizes because he can't find it in himself to bury people who aren't fully dressed, and no one would ever know, but he would know and he couldn't live with himself. Everybody I spoke to has these little things that they do that no one would ever notice. I think more generally, no one notices just how much they do.

During COVID, in the very early lockdowns in London, we had a thing where everybody stepped out onto their doorstep at about six o'clock every night and bashed on pots and clapped, and that was all for the doctors and the nurses and the key workers, but I don't think anyone was clapping for funeral directors.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Why do you suppose? Is it just the fear of death?

Hayley Campbell: It is the fear of death. No one ever wants to think about it, but I think not thinking about it makes it worse. Part of my book is just-- I always think that if we speak in euphemisms, and the funeral industry is rife with euphemisms and they're trying to deal with our feelings, but I think once you start speaking in euphemisms, you're giving your imagination space to run wild and it will fill it with horrors.

With my book, I didn't set out to tell you how to feel about death and dead bodies, I just wanted to go behind the scenes and see what was happening and tell you the truth, tell you what it was like. Parts of my book are brutal and some of it is really tender and sweet, but it runs the whole gamut of human emotions because that's what happens behind the scene.

This book isn't something to assuage your fears, I think it's something to help. I'm noticing with lots of readers, it's kind of a Rorschach test how people take it, and I thought that might happen because death is so subjective, so people bring all sorts of baggage to it.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Let's talk about the brutal and the, perhaps, a bit more tender on the brutal side. You talk with executioners.

Hayley Campbell: I wanted to speak to an executioner partly because this was the one chance I was going to get, I thought, and he didn't quite fit into my scheme of people who care for the dead, but executioners and the whole execution team are like people who work with the dead, they're hidden from us. When we hear about capital punishment being argued about, when we hear about executions going through on the news, nobody's talking about the people who had to carry it out and then drive home to their families and go to sleep and wake up the next day and go to work.

I wanted to find somebody who did do that and to ask him, "How do you deal with this?" I found, Jerry Gibbons was his name. He was the state executioner for Virginia for 17 years. I found him because, you might remember some years back, the State of Arkansas was trying to rush through a series of executions in a very short space of time because the lethal injection chemicals were approaching their use by date, and so lots of people who worked in prisons and who worked on the death teams wrote this letter to the governor pleading with him, "You can't do this because it puts so much emotional stress on the people you are employing."

Jerry was one of many people who had signed it, but he was the only person who-- It said wardens, chaplains, and he was the only person who said executioner. We all know that executioners are historically anonymous. They wear the big hood, we don't see them, and so I wanted to know what happened. He didn't mean to out himself, somebody told a local paper, which is how his wife found out, because for the whole 17 years that he held that position, he never told his wife. Whatever stress he was carrying, she would then carry too and he didn't want her to go through what he was going through.

When I spoke to him, he really seemed like a man who was struggling with some kind of PTSD that he wasn't quite acknowledging. I asked him how he dealt with going to the executions. He killed 62 people, and he said he could eat breakfast on the execution morning, that was no problem, but he would never look at it himself in the mirror on the day of an execution because he didn't want to see himself as the executioner.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Another point of brutality was difficult for you, encountering the autopsy of an infant. Can you tell us a bit about that experience?

Hayley Campbell: Well, I had gone to see the autopsy of an adult, and I was fully prepared to see that, and seeing the autopsy of an adult was completely fine. I even held his brain. While that was happening, there were other autopsies happening in the room, one of which was a little baby. They were doing an autopsy to figure out if the mother had killed him or if he had died in his sleep because SIDS is only ruled until everything else is ruled out.

While the autopsy was going on, I was far enough away that it didn't seem real, but it was at the point when the baby had all been sewn up and they were washing it in a little tub. He had bubbles up around his shoulders and he started to sink under the water, but something just threw me because it wasn't an autopsy in a hospital scene anymore, it was just this scene of something domestic gone horribly wrong and it took me weeks to get out of bed, really.

I just came home, went to bed and only crawled out when work demanded it, but a way of figuring out why I felt like that and what I was supposed to do with it was I contacted a baby loss charity because I thought, "I want to speak to a midwife." Something I had never considered was that a midwife is a life worker and a death worker because not every pregnancy ends in a bouncing baby.

This charity put me in touch with a woman called Claire Beasley, who is a bereavement midwife, and she delivers only dead babies or babies who aren't going to live very long. Of all the people I spoke to, I think she is the most hidden and one of the most important. I never would have come across her unless I myself had a baby who died. She had been at the birth of a baby who was so premature he wasn't going to live. The mother knew this, but even so, when he was born, he was breathing, so there was a little bit of hope. She said to Claire, "Please do something."

At that point Claire was this young midwife and she didn't know what to do. It was only years later when she did a course in bereavement training that she realized that she could do something. She couldn't bring the baby back to life, but she could make the situation better for the parents.

Melissa Harris-Perry: You also write about the bodies of the dead, ourselves, our bodies after our death, and the ways that they can still even in death tell our stories.

Hayley Campbell: That's the whole point of doing an autopsy, it's to make sure that nobody died for reasons we didn't know. That's why autopsies are done in murder cases, they're done even in cases if you die spontaneously in your sleep and you haven't seen a doctor for a while and so they can't say how you died. You are, like the TV show is called here in the UK, it's called Silent Witness, you are a silent witness, you are giving up the evidence that you have to say how you died.

There are cases where I was asking the autopsy women, and it is all women down there, weirdly, cases that stuck with them in their minds, and Laura who does them, she said that there was this one woman who came in who had died and her family said, "Oh, she's a drug addict, so this is just a formality, really." Laura approaches every body with an open mind, "Tell me your story yourself." She opened up this woman and she said there was no part of her body that hadn't been touched by cancer. This poor woman was self-medicating with drugs. She was in pain.

Laura found that the point where the cancer had started was in her uterus, and there is a strong genetic component to gynecological cancers. She urged the family to go and get tested to see if this could happen to them. That's a way that the dead is helping the living.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Is our ability to talk about confront death about being desensitized or is there some other way you might define it?

Hayley Campbell: The thing I found with everybody I spoke to was that not one of these people who see death and dead bodies and horror and trauma every day, not one of them was desensitized to it, but each of them had a way of dealing with it. They weren't detached in a cool way, they were detached in a way that merely helped them to function and do their job. They all have their limits that they wouldn't cross and each of them was personal to them. What I really liked was hearing how everybody who does these jobs in the death industry has another idea of another job in the death industry that they could never do, they think it's too far.

When I worked in the crematorium for a day, pushing coffins into the fire, I was telling the old man who worked down there, and he'd been doing this job for 30 years, I was telling him very excitedly that I had recently dressed a dead man for his coffin and found it to be this profoundly moving experience. He looked at me like he was repulsed. He said, "Oh, I could never do that. That's spooky." I'm like, "You've been in this basement with coffins for 30 years and that's your limit?"

The women who do the autopsies, they can take a body apart and literally hold a heart in their hands, but they won't read the suicide note that comes in the coroner's report because it's too emotionally connecting for them to the body, and if they are connected to this body, they can't do their job properly.

Melissa Harris-Perry: You spoke at the beginning of our conversation about discovering that this book is a bit of a Rorschach test for your readers. What is this Rorschach test telling you about us your readers?

Hayley Campbell: I think there are people who are so curious but come in with so much baggage that they can't see what I'm telling them. I think what it tells me most is that the preconceived notions that society has put upon us are so ingrained, it is going to take so much work to try and untangle them. I've seen people saying, "I appreciate this book, but I felt that she found too much joy in the work that she was seeing done." The joy that I show in the in the work is because I'm sharing in the joy that these people are doing with their work. They feel like they're doing something good in the world.

I think the idea is that people who work in death must be somber and it must be depressing and it must be dark and bleak. That's just not the case. All it tells me is that we really need to just sit down and see what is going on and try and make up our own minds because there is far too much in the world that is telling us what to think and what to do and I don't think it's doing us any good.

Melissa Harris-Perry: Hayley Campbell, freelance journalist and host of the BBC podcast Must Watch. Also, author of the new book, All the Living and the Dead. Thank you for joining us.

Hayley Campbell: Thank you so much for having me.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.