Episode 1: The Past Is Present

KALALEA: This episode of Blindspot: Tulsa Burning contains descriptions of graphic violence and racially offensive language.

When I was about seven years old, our house was robbed. It was on Halloween, we just got home after trick-or-treating… And my mom, she unlocked the front door, and then stopped, and took a really big breath.

I remember seeing our stuff thrown all over the place.

It looked like they took everything: our furniture, stereo equipment, even the television. But most importantly to me, they took the pearl necklace my aunt had given me for my birthday.

It was the first time I truly felt wronged.

We never found out who robbed us -- but whoever it was, they not only took, but they gave. They gave me worry and confusion. And I was mad. I wanted my necklace back.

We never talked about the robbery. We just weren’t that kind of family, you know, who talked about their feelings, or took time to revisit certain painful memories.

But that feeling of being violated has stuck with me. It might be the reason why, as an adult, I’ve always made sure there’s a door or some extra layer between the outside world and me.

I still lock my bedroom door, every single night, even some 40 years later.

[SONIC SHIFT]

100 years ago, in Tulsa, Oklahoma, an entire neighborhood was burned to the ground by a massive mob.

That neighborhood was Greenwood: a thriving community where thousands of hard working people lived and worked in the businesses they had built for themselves and their families.

And those people... they were Black.

I wish that didn’t matter so much, but that distinction is important because of the world we live in… because the people who destroyed Greenwood -- were white.

The night of May 31st, and into the morning, hundreds of small children hid under their beds while their homes were being looted and set on fire.

[VOICES OF MASSACRE SURVIVORS IN THE BACKGROUND]

Parents, uncles, aunts and grandparents were shot to death on their porches, or while kneeling down, praying for mercy. Others were shot in the streets as they ran from the fire. Emergency services, like Tulsa’s fire department, let Greenwood burn. Airplanes, deputized by the local authorities, dropped turpentine bombs from the sky.

And when it was all over, hundreds of Greenwood residents were dead -- and 60 people were indicted -- all of them Black. Not a single white person was charged with larceny, arson, or murder, or anything else. Even when they proudly displayed the jewelry, furs, and other belongings they took from their neighbors.

[PIANO MUSIC STARTS]

So when I think about what happened to Greenwood -- to that community of people who looked like me, people whose skin was Brown, like mine, people who liked nice things like me, people who made mistakes, people who struggled and persevered... I just can't imagine how those two traumatic days reverberated in every cell of their bodies -- in every move that they made from that moment forward. And I think about their children’s bodies and how generation upon generation absorbs an event like this -- and how its memory mutates from one descendent to the next.

How did the residents of Greenwood make sense of what was taking place on a hot summer night in 1921? And how are their descendants reckoning with that past today?

[THEME MUSIC STARTS]

From The History Channel and WNYC Studios, this is Blindspot: Tulsa Burning.

My name is KalaLea.

On this show, we’ll look back at the blindspots in our collective memory -- and the histories we might not know, but need to. This season: The Tulsa Race Massacre.

Six episodes that explore what led up to it... and how we’re still feeling the impact of the violence today.

We’ll be going back to one of the most lively and prosperous all-Black towns in American history.

QURAYSH ALI LANSANA: Wealth and economic independence born out of necessity of Jim Crow segregation.

KALALEA: We’ll revisit the founding of Oklahoma, the discovery of oil and the creation of wealth beyond belief…

ELI GRAYSON: basically the Saudi Arabia of the world in those years

KALALEA: … and we’ll find out: What were the forces that allowed Greenwood to flourish? And why did the people outside its borders want them gone forever?

VANESSA ADAMS-HARRIS: In its essence, it’s about moving people off of land for the sake of redevelopment.

KALALEA: We’ll also hear from survivors and their descendents, people whose lives were transformed by the attack. 100 years later, they’re still bearing the cost.

TIFFANY CRUTCHER: When she shot my brother, it's almost like she killed

me too.

KALALEA: The Massacre has affected us all, whether we know it or not. Because the people and policies that threatened Greenwood continue to threaten communities all over the country.

Over the next six episodes, I’d love for you to ask yourself: What would it take for history to stop repeating itself?

[THEME MUSIC ENDS]

Episode 1: The Past is Present

It all started in an elevator.

Only the two people involved really knew what happened there… and their voices are missing from the historical record.

So much of this story has been strategically erased -- cut out of newspaper archives, and kept out of school curricula.

But for a hundred years the story has gone something like this: on May 30, 1921, in an office building called the Drexel … in what was then Jim Crow Oklahoma ... a 19-year old African American shoe-shiner named Dick Rowland -- allegedly touched the elevator operator, Sarah Page -- who was white.

Whether he assaulted her, tripped and fell, or they were in a romantic relationship... that no longer mattered. The morning after the incident, Rowland was picked up by police and accused of assault. He was then arrested and locked up in the courthouse jail.

Within a couple of hours, a large group of armed white men -- along with some women and children -- showed up to the courthouse -- threatening to lynch Rowland, something that was happening to so many Black people at the time.

Shortly after, a smaller group of Black men -- also armed -- arrived to defend him.

There are many stories of what happened in the area surrounding the courthouse that evening. Some say that two men -- one white, the other Black -- got into a fight over the Black man’s gun. Others say a random shot went off and all hell broke loose.

What we DO know is that the following morning, thousands of white people crossed over into Greenwood, the Black community, and burned down scores of homes and businesses.

For years, it was called a Riot -- which suggests that the violence was mutual or random.

It was neither.

There are dozens of eyewitness accounts that say that at precisely 5 o’clock in the morning on June 1st, a loud whistle blew, and as if on cue, a hoard of white people descended on the neighborhood, guns firing.

And some of those weapons were enormous machine guns, the kind issued by the military that some white soldiers brought back from fighting in World War I.

This was a coordinated attack.

CHIEF EGUNWALE AMUSAN: Most of the people who consider themselves historians say that a mob invaded Greenwood … that's a lie.

KALALEA: I want to introduce you to Chief Egunwale Amusan -- a well-built, stocky man with a cheerful-looking face. Born and raised in Tulsa, he’s a descendent of a Massacre survivor -- his grandfather, who died some years ago.

KALALEA: Can you tell me about him?

AMUSAN: My grandfather and I, we had a really close relationship. I honored him, I honored his family values, his ethics, you know, everything about him was just beautiful. My grandmother say, he was a man's man, you know?

KALALEA: And for decades, Amusan has been advocating for survivors, descendants and their families. His mission in life is to set the record straight about what happened to thousands of Black Tulsans in 1921.

[AMBI of TOUR TAPE ENTERS]

AMUSAN / TOUR: You have to ask yourself: what was Greenwood? If it wasn’t a street, what was it? By the time we’re finished, my hope is you’ll feel like you walked into a 1921 version of Wakanda, and oil is vibranium.

KALALEA: One of the ways he does that is by providing tours of Greenwood, which he calls The Real Black Wall Street Tour.

KALALEA: I want to know from you, like, what have people gotten wrong? What is the real story?

AMUSAN: One of the reasons we named it the Real Black Wall Street Tour is because there were other tours taking place, but they were watered down. I wanted it to be so tangible that you felt like you were living the experience, as I tell the story. Right, I wanted you to be able to smell Greenwood. I wanted you to be, to hear the music on Greenwood. I wanted you to be able to smell the burning on Greenwood. I want you to have a total holistic experience.

[AMBI of TOUR TAPE HERE]

AMUSAN / TOUR: You could go do any and everything within walking distance in the Greenwood district. Most people have no idea that the original Cotton Club was right here in Tulsa, Oklahoma...

AMUSAN: We start it right in the core, in the heart of Greenwood and I show people. What was, and what is no more…

[AMBI of TOUR TAPE]

AMUSAN / TOUR: This is the location of the Stratford Hotel. In 1918, this was declared the crown jewel of hotels in the United States of America, owned by a Black man...

AMUSAN: I take them to the places where bodies were dumped. I take them to the home of Wyatt Tate Brady, the city founder, Klansman.

AMUSAN / TOUR: He said yes, I’m a member of the Klan, I’m a proud member of Klan, so was my father a member of the Klan.

AMUSAN: ...so that they can see that he built a home that is the replica of Robert E. Lee.

I take them to Standpipe Hill...

AMUSAN / TOUR: They occupied these hills and fought for their lives.

AMUSAN: ...the battleground location, where Black men fought to defend Greenwood.

This explains why it was necessary to bomb Greenwood, because there was a losing battle on the ground.

KALALEA: How do you know this?

AMUSAN: You got 150 survivors in the room, and out of 150, 75 are saying, yes, we saw those planes drop things out of the sky. In fact, the most articulate of the survivors, the most powerful one -- Professor Dr. Olivia Hooker, before she passed, she always said, “Yes. We, I saw them drop, uh, things out of the planes.” A little girl saying I saw them drop things out of the plane, not understanding what she's seeing or what's happening.

[PAUSE / MUSIC]

KALALEA: In the early 1900s, Greenwood was referred to as a Black Mecca, a Promised Land for those with darker skin tone. I say this because there were Black people from all over the country who lived in Greenwood, as well as Native people.

In 1921, Greenwood counted two schools, two newspapers, a hospital, more than a dozen churches, a public library, two movie theaters and dozens of other businesses, all Black owned and operated.

AMUSAN: When I do tours, I say, have you ever been anywhere with 600 Black businesses are located -- during a time period like that, right?

No. I have yet to meet anybody who can say that. You have to go to the continent to experience something like that.

I take them to different places throughout the Greenwood district and even around the entire district so that they can see how much was actually burned, because we can’t imagine 10,000 Black people in one place.

KALALEA: The population of Greenwood in 1921, just before the massacre, was somewhere between 10 and 12,000 people -- all living within about 40 square blocks.

That reminds me of Harlem during its heyday. But the difference in Greenwood was that Black people owned a substantial amount of land.

Not sure you can say the same for the residents of Harlem back then.

Chief says that Greenwood was a city within a city.

AMUSAN: The city of Tulsa called it, the white citizens of Tulsa, called Greenwood “Niggertown” or “Little Africa.” Right, if you comparing a community to a continent, it's not a community, right? And that's really what they represented because they were like a little nation.

KALALEA: I’m pretty sure that Tulsans were not complimenting Greenwood on its size or presence. Calling anything “African” back then was a denigrating remark. But I love that Chief took that as a compliment.

[BEAT/MUSIC]

Greenwood streets were lined with Sycamore, Oak and Cottonwood trees. Many of its residents lived in boarding houses, but others lived in more elaborate homes.

AMUSAN: We're talking about two story homes. You had homes that were carports... you know, I mean, most of us don't have houses that exquisite today.

KALALEA: To give you a sense of the kind of wealth there: O. W. Gurley, one of the founders of Greenwood, was worth approximately 5 million dollars in today's money, and J.B. Stradford owned a 54-room hotel which was valued at almost $2.5 million. Both men had a vision for Greenwood and were outspoken supporters of entrepreneurship, self-reliance and Black ownership.

AMUSAN: And then when you look at the photos, I want people to pay attention, look at the houses that didn't get burned down. You know why they didn't get burned down? Because the white people who came into burn could not believe that a Black person lived in those homes. They said it is impossible. So they didn't burn it.

KALALEA: But the whites destroyed the homes and businesses of both Gurley and Stradford, and nearly every other Black person who lived in Greenwood.

AMUSAN: People want to say, Oh, it was the Klan and it was, you know, this mob violence. No, it was the police department. It was the city of Tulsa. It was the state of Oklahoma who failed to protect the constitutional rights of these citizens. That's what we really need to understand.

Because anytime a police department says we're going to deputize 250 plus men, then the Sheriff's department does the same thing. Hundreds of men … that’s state-sanctioned murder, that’s state-sanctioned genocide.

KALALEA: And in pictures taken of the neighborhood from the next day… it really does look like the buildings have exploded - shattered bricks are everywhere -- it’s like a war zone.

But the day after the Massacre, June 2nd, newspapers across the country told a different story. The number of dead varied widely, from dozens to hundreds.

And get this: the LA Times even suggested Communists had infiltrated Greenwood and they were to blame.

The Governor of Oklahoma called for an investigation, which ultimately pointed the finger at two different groups: militant, outspoken Blacks who didn’t know their place, and corrupt law enforcement.

Today, we’d call them “bad apples.”

Basically, the thousands of other white Tulsans who perpetrated the attack were within their right to burn and destroy Little Africa.

KALALEA: What, what impact has it had on, on you and the community? What can you see?

AMUSAN: Well, what we see is the reflection of 1921. And I don't mean figuratively. I mean, literally,

KALALEA: Tulsa is as segregated today as it was 100 years ago. The white and Black communities are divided by two major pieces of infrastructure: One, the Frisco railroad tracks. And, two, I-44, an interstate highway, which was built straight through Greenwood in the late 50s.

KALALEA: And where are things now?

AMUSAN: If you come to North Tulsa, it looks as if the burning had just happened because there's nothing left. If you come there today, it will look as empty as it did the day they burned it

KALALEA: North Tulsa is predominantly Black and South Tulsa, a short drive away, is predominantly white.

In white Tulsa you’ll find large multi-story homes, manicured lawns, and high-end shopping malls.

But just as Chief Amusan mentioned, in North Tulsa, Black Tulsa, it’s as if someone hit the pause button. While some areas have been rebuilt, there are also vast empty stretches that extend for miles. Plywood tagged with graffiti covers the windows and doors of homes, shopping plazas and other commercial spaces.

And you can still see the damage the burning had on the land.

[AMBI of TOUR TAPE]

AMUSAN / TOUR: It is a reminder of the damage that Greenwood...it’s like

Greenwood is still burning

KALALEA: There are also blocks and blocks where nothing has been rebuilt since the 1920s. Staircases leading to homes that don’t exist anymore. Steps that lead to nowhere. Those stairs are a constant reminder of the harm inflicted not by some storm or distant enemy, but by Greenwood’s neighbors, employers and city officials.

AMUSAN: And then you deal with it on a psychological level, right?

Myself and other descendants that I personally know. We've examined how a lot of this has been internalized because when you're abused and you keep it a secret, what happens? Right? You turn in on yourself or each other.

[BEAT/MUSIC]

KALALEA: Many of the Black people who stayed in Tulsa after the massacre say they received threats that if they talked about it or sought restitution, it would happen again. And keeping this tragedy a secret meant that their loved ones were protected. You can’t be afraid of something if you don’t know it’s possible.

And for white people, many were ashamed or scared to expose their more violent neighbors. Or even that they would be held accountable for the actions of their parents or grandparents.

The result: generations of Tulsans didn’t know about the massacre at all.

CRUTCHER: To be quite honest, Black Wall Street, that's not something I

really knew about growing up in Tulsa.

KALALEA: James Baldwin once wrote: “people are trapped in history and history is trapped in them.”

This is Blindspot.

[MIDROLL]

KALALEA: This is Blindspot: Tulsa Burning. I’m KalaLea.

CRUTCHER: For me, life was good. Didn't know anything about racism. Didn't really realize that there was a racial divide. I just remember growing up having a good life.

KALALEA: Meet Dr. Tiffany Crutcher. Tiffany is a physical therapist who has the most beautiful smile. She was born and raised in Tulsa.

CRUTCHER: You can't come to Tulsa without going to a barbecue joint and

eating a barbecue bologna sandwich. You can't come to Tulsa without

having Coney Island. You can't come to Tulsa without --

KALALEA: Wait, wait, what's a Coney Island?

CRUTCHER: Island is a hot dog joint with some petite Coneys with this really great chili sauce. And it's just simply amazing.

KALALEA: Mmm… I love hot dogs.

[BEAT]

For Tiffany, growing up in Greenwood was kind of idyllic. Her home was the neighborhood spot. You know, the kind of place where all the kids wanna be... Where there's food, and warmth and lots of love...

KALALEA: So I want to talk a little, just go back to like, what was it like growing up in Tulsa in the... seem like... must be like, late seventies, eighties? What was that like?

CRUTCHER: I was raised in a typical, I would say lower-middle class home, mom and dad worked really, really hard. My dad worked for the city of Tulsa and my mom was a music educator. And life was really good. You know, I'm one of four children, the only girl and what I remember is playing outside in a community, in a village, where the neighbors knew who you were. And there was always a lot of children at our house. And the North Tulsa community, the Black side of Tulsa, was just ripe with tradition, heritage, legacy.

KALALEA: Except when it came to one key incident.

Tiffany says she went to some of the best schools in Tulsa, but she didn’t learn about the events of 1921 until college -- at Langston University, an HBCU.

CRUTCHER: When people from Chicago or Detroit, California, New York would ask, where are you from? And, uh, I would say Tulsa, Oklahoma, everybody would say, Oh, Black Wall Street, or the Tulsa Race Riot. And I had no idea what they were talking about.

KALALEA: Finally, she asked her dad what happened in Tulsa in 1921.

CRUTCHER: And that's when he shared with me that his grandmother, my great grandmother, Rebecca Brown Crutcher - we called her Mama Brown - um, her community was burned down and she had to flee in fear of her life.

KALALEA: Tiffany's father grew up not knowing about the massacre either. It wasn’t until he was a young man, in 1968...

CRUTCHER: He came back from Vietnam, and Martin Luther King had gotten assassinated and riots broke out, you know, all over. And that's when his grandmother, she whispered and said, something like, that happened here.

KALALEA: The cause of the unrest was vastly different, but the threat of violence was still so fresh in her mind. And so Tiffany's father listened to his grandmother tell the story of her escape from Tulsa after one of the deadliest massacres in U.S. history.

CRUTCHER: They jumped on the back of a truck with a neighbor and they fled to Muskogee, Oklahoma, which was a neighboring county, fleeing, trying to get out of harm's way.

KALALEA: How old was she around that time, do you know?

CRUTCHER: Like, uh, like a teenager maybe around 19 or, or 20. Yeah... so she definitely could have been able to tell the stories, but my grandmother never shared because she was forced into silence...

KALALEA: Were there people sending death threats, or, describe... What do you mean?

CRUTCHER: She shared with my dad that they told us we better not ever say anything. If you do, you're going to be lynched next, you'll die next. And that's what I've heard from a lot of family members, a lot of descendants, that same story. And a lot of them just didn't want to talk about it. They blocked it out of their mind. They deal with a lot of internalized grief.

KALALEA: Tiffany never got the chance to learn more about her great-grandmother’s experience. Because she died when Tiffany was in junior high school.

CRUTCHER: What was my great-grandmother thinking as the violence was taking place? Um, what was it like seeing your entire community destroyed in the era of Jim Crow and Klansmen and -- with airplanes dropping bombs and, and police officers allowing deputized Klansmen to, to, to shoot at innocent Black men with their, their hands up. It's just, man. I wish I would have asked her more questions.

Thank God she survived, or I wouldn't be here today.

[PAUSE]

KALALEA: I want to pause for a second on something Tiffany said: “innocent Black men with their hands up.”

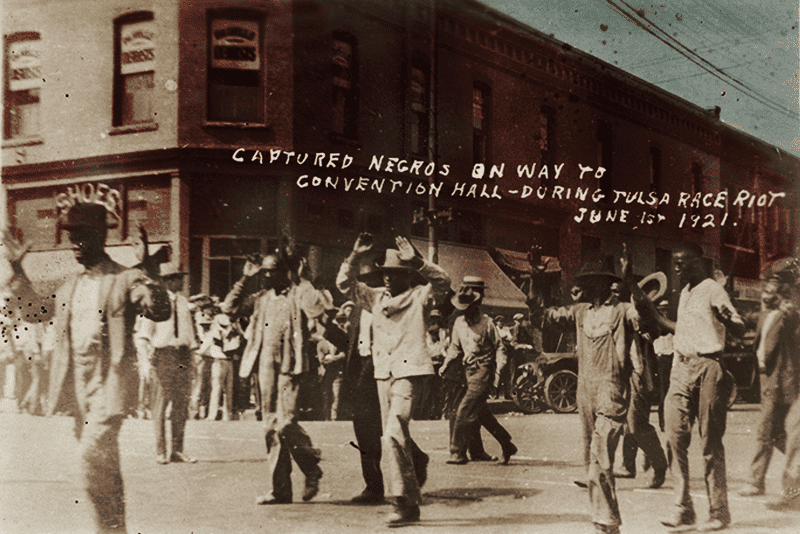

There’s a photograph from 1921 I keep coming back to. It’s one of several images documenting the aftermath of the massacre that were made into postcards -- much like the postcards produced and distributed after a lynching.

This picture was a souvenir for some of the white people to send to their families and friends.

It shows a group of Black men with their hands up in the air as if they were under arrest. The men are walking in the middle of a street, their eyes cast downward, one man’s hat is falling off his head.

And written by hand across the top of the image, it reads: “Captured Negroes on the way to convention hall during Tulsa race riot, June 1st, 1921.”

The men are walking to one of the makeshift internment camps.

They don't look like rioters. They look helpless -- even compliant. Like people who just lost everything.

CRUTCHER: Then I, I fast forward to what happened to my twin brother, Terrance in 2016. And I see that same visual with the helicopter.

KALALEA: Can you tell me what happened?

CRUTCHER: I remember it, KalaLea, like it was yesterday. Uh, it was a Friday.

KALALEA: She was sitting at a restaurant waiting for a friend when she got a call from her cousin.

CRUTCHER: She said, have you called home lately...

KALALEA: ...She was living in Montgomery at the time...

CRUTCHER: I said not in a couple of days. And then she paused, and she finally said it's about Terrence. And I said spit it out. She said I heard he was shot... and they say he's dead.

I really didn't believe it but I had that feeling of sickness. I was just praying ... God, please don't let this be true. Please don't let this be true.

KALALEA: Then her father called.

CRUTCHER: My dad, my hero, my father on the other end of the phone hysterical just screaming:

“They killed my son. They killed my son and they won't let me see my son. We're in the hospital. They're treating us like criminals. I'm so upset.” And I said "Dad, who killed Terence?” And he said, the police. And I just lost it.

I lost it because I remember when Freddie Gray got shot, when Mike Brown got shot, I was one of those people who said we have to do something about this when Trayvon Martin was killed, you know, I was glued to the TV screen and never in a million years would I have thought that I would be in their shoes.

KALALEA: Early the next morning, Tiffany was at her parents' home in Tulsa when homicide detectives arrived to explain what had happened to her brother.

They said that on the evening of September 16th, Tulsa city officer Betty Jo Shelby -- who is white -- saw Terrence standing in the middle of a 2-lane road, a little ways from his stalled car. The officer approached him and told him to get on his knees. He didn’t respond to her commands and instead stood with his hands up. Shelby believed he was under the influence of something or having a mental health issue. She called for back-up and drew her gun.

A helicopter arrived and recorded the final moments of Terence’s life.

Less than thirty seconds after back-up arrived, an officer tased Terence, and then Shelby shot him once in the chest, while another officer tased him again.

The police left his body on the side of the road for more than two minutes before anyone checked on him.

The whole encounter lasted about a half an hour.

Terence T. Crutcher, Sr., father of four, was pronounced dead at the hospital.

He was 40 years old.

CRUTCHER: My brother had his hands in the air. My brother wasn't committing a crime. My brother wasn't suspected of committing a crime. My brother wasn't a fleeing felon. My brother was in crisis mode. He needed help, but instead he got a bullet. And… when she shot my brother, it's almost like she killed me too.

KALALEA: In recent years, the Tulsa Police Department has been under investigation for corruption and misconduct. But a jury acquitted Officer Betty Shelby of 1st-degree manslaughter. She resigned and ultimately found a job as a deputy sheriff in another county.

And the Crutcher Estate, they filed two lawsuits against the city of Tulsa for Terence’s wrongful death. One was dismissed, and the other is still pending.

Tiffany left her physical therapy practice to be a full-time activist.

CRUTCHER: There's a historical context to this, to police brutality. This has been happening since we've been brought over here, uh, from Africa, you know, during the slave trade. And so this era of police brutality is just a continuation of racial terror violence, uh, that Blacks in America that we've been experiencing in this country for centuries. The laws that are written, give police officers the authority to commit legal murder.

As a woman who stands on the shoulders of our ancestors, of the community of Greenwood and Black Wall Street, I refuse to stand by and allow lies to be told.

KALALEA: For the descendents of the massacre of Greenwood, there has been no justice, no restitution. The people who were responsible have never been held accountable.

But right now, the city of Tulsa is confronting its past like never before.

Public schools are finally including the massacre in their history curriculum. There’s a new lawsuit calling for reparations. And archeologists have discovered mass graves that they believe contain bodies of massacre victims; and what they find could answer questions that have haunted the city for a century...

What would it take to make it right? To allow Tulsa to truly heal from this painful past?

And what would the city -- and our country -- look like if they succeed?

That’s this season, on Blindspot.

[THEME MUSIC]

Blindspot: Tulsa Burning is a co-production of The History Channel and WNYC Studios, in collaboration with KOSU and Focus Black Oklahoma. Our team includes: Caroline Lester, Alana Casanova-Burgess, Joe Plourde, Emily Mann, Jenny Lawton, Emily Botein, Quraysh Ali Lansana, Bracken Klar, Rachel Hubbard, Anakwa Dwamena, Jami Floyd, and Cheryl Devall. The music is by Hannis Brown, Am’re Ford, and Isaac Jones.

Our executive producers at The History Channel are Eli Lehrer and Jessie Katz. Raven Majia Williams is a consulting producer. Special thanks to Andrew Golis and Celia Muller.

I’m KalaLea, thank you for listening.

###