Out of hope? Maybe stop for a sandwich and a song.

[music]

Regina de Heer: Would you consider yourself a naturally optimistic person?

Interviewee 1: I'd say it's a little bit of both. The goals that I want to achieve here are pretty set. If I don't be optimistic, I don't think I'm going to achieve it.

Interviewee 2: Not at all. Actually, no.

Interviewee 3: I'm very optimistic, yes.

Interviewee 4: I feel optimistic about today, so don't have any reason to feel it will be different.

Interviewer: Would you consider yourself a normally optimistic person in that regard?

Interviewee 5: More who I am.

Interviewee 6: Just to know that how many things need to go right every single day for one to get out of bed, go through the day, so I would say in that sense, I would definitely consider myself an optimist, that things are working the way they intend to.

[music]

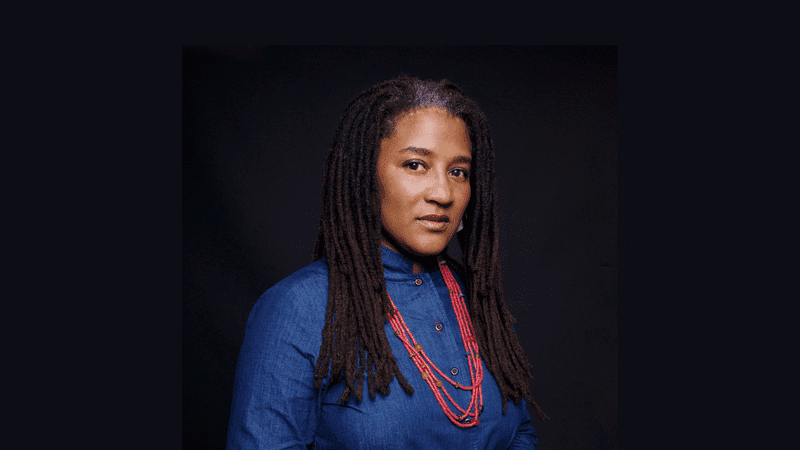

Kai Wright: It's Notes from America. I'm Kai Wright. Welcome to the show. For today's show, I want to share a conversation I had with playwright, Lynn Nottage, back in 2021. Lynn is the still the only woman to win two Pulitzer Prizes for playwriting, which of course is a sad fact, actually. Nonetheless, a statement about the way her work just forces you to sit up and pay attention. Lynn is as much a journalist as a playwright. She's chronicling the American experience and focusing her art on big, hard questions about opportunity and justice, and human rights.

Yet, her work is covertly optimistic. When I first had this conversation with Lynn, she had three shows headed to the stage that season, two of which got Tony nominations in the end. She wrote the book for the musical MJ, about Michael Jackson. She developed an operatic version of her popular early show, Intimate Apparel, and her dark comedy, Clyde's, was all about a group of people trying to find work and build their lives after getting out of prison.

Notably, when Clyde's was on Broadway, it did something really unusual for the industry. Part of the run was streamed online, so people didn't have to come all the way to New York to see it due to the pandemic. Anyway, here's my conversation with playwright, Lynn Nottage. We talked about her career exploring the emotional terrain of class and race, and about the deep lessons she found in a sandwich. Lynn, thank you so much for coming on the show.

Lynn Nottage: It's my pleasure. Thank you.

Kai Wright: You are as near as I can tell, the busiest person in theater.

Lynn Nottage: I am. That is not a lie.

Kai Wright: I'm really humbled that you have made this time for us. I guess before the pandemic, it was unheard of to offer streaming tickets to a Broadway show. Obviously we all started doing unheard of things with screens in the course of the pandemic. It's one of a few ways you've leaned into changing theater and the way it does business. You'd been one of the more vocal artists in that regard that we can't go back to normal when we get back. How do you think it's going?

Lynn Nottage: There's some ways in which we're back and it's status quo, but I do think that a lot of really exciting things that have happened that started during the pandemic, particularly since we were in the midst of this cultural reckoning, and it really forced the industry to begin to interrogate their practices. Some people really stepped up to the table and began shifting the way their theaters look.

Some people is always a resistant to change. I can only speak anecdotally about the rooms that I'm in and the institutions that I'm interfacing with, and it feels as though they heard that they're really trying to figure out how do we create a theater that is more inclusive, that is more welcoming, that really is reflective of the kinds of diversity that we have in our culture.

Kai Wright: That's an optimistic view. A refreshingly optimistic view. There's so much cynicism about change, in general, in so many spaces in our society.

Lynn Nottage: I'm an optimist, Kai. I am someone that in order to get up in the morning, I have to imagine that I'm going to be facing a day that was better than yesterday. I think I bring some of that optimism with me into the rooms, into the rehearsal spaces that I go into. Just speaking about some of the rooms that I'm in, we've had people in diversity folks who've done training, which has sunk in. The musical that I'm working on, it's probably one of the most beautiful companies that I've ever encountered. It's a large company, and there's a lot of room for dissent and conflict, but because of the work that we've been doing, it really feels quite different than the space might have prior to the shutdown, COVID.

Kai Wright: The musical is MJ the Musical and we'll return to that in some detail a little later on. Let's talk about Clyde's. Let's talk about the show itself. It's a dark comedy set entirely in the kitchen of a truck stop diner run by a tyrant of a woman who only hires people who've been incarcerated. Because they struggle to get hired with a record anywhere else, they are dependent upon her supposed generosity as she lords over them. I guess first off, Lynn, this is not exactly a welcoming Broadway setup to me, a comedy about formerly incarcerated people being abused. Why was this on your heart right now?

Lynn Nottage: I've been thinking about this play for a long time. We originally premiered it in Minneapolis before COVID. It really comes about from the work and interviews that I was doing while I was researching my play, Sweat, in Reading, Pennsylvania. I came across so many people who were open and generous, and who also happened to be formerly incarcerated. I began listening to their stories.

Many of them were incredibly heartbreaking, and I want to figure out how can I tell this story about folks who are in limbo, in a liminal space who really feel stuck and trapped because of their circumstances. Many of the folks that I interviewed had been out of prisons from anywhere from a week to a year. They had one thing in common is that they kept hitting up against the wall when they were looking for opportunity, whether it'd be housing or whether it'd be jobs, or even whether it was reintegrating with their families.

They hit that box that you have to check when you're going for employment that says you're incarcerated. Then it became this door that slammed in their faces. I was really interested in how do people who are in a liminal space really resurrect their lives? How do they get out? I found this space, which was Clyde's, a little box, which is a sandwich shop on this very nondescript stretch of road in Berks County where I could grapple with some of these issues.

Kai Wright: It often left me off-kilter a bit because it's almost a screwball comedy at times, just laugh out loud, funny, almost slapstick. Then also as a viewer, you aren't sure whether you're supposed to be thinking something is funny sometimes. It's a little like, wait, uh-oh, maybe I shouldn't be laughing at this situation. In some ways, that's a homework of your work, isn't it? Do you agree with that?

Lynn Nottage: Yes, I do. One of the things that I love about humor is that it is disarming. It's all those things that you just said, but laughter also is this fantastic conduit, which you can filter through truth. I think that an audience, when they're laughing, in some ways they're more open. The mouth is open, the body is open and relaxed. I think that they're more ready and willing to engage with complicated ideas. I really love using humor, and even plays like Sweat and Ruined which are considered to be tragedies, I think that humor is always threaded throughout it.

Kai Wright: I like that idea, your mouth is literally open. You're laughing. You're ready to take things in. Well, there was a lovely profile of you, or I thought it was lovely in T Magazine. The writer made an astute point in this regard that your work is always really accessible and familiar to audiences in form but incredibly challenging in content. Do you agree with that?

Lynn Nottage: It's interesting because she asked me, do you agree with that? I had to think for a second. I think, yes, it is true. I actually embrace that. One of the things that I am super proud of is that my work really speaks to a cross section of people that is accessible in ways that I feel some of my colleagues work, which is brilliant and challenging, and wonderful, but it's often geared toward one very small group within the audience.

What I feel I endeavor to do is to speak more broadly. I think it has a lot to do with the way in which I was brought up. I grew up in Brooklyn in a multicultural community. I was in dialogue with lots of people the moment I stepped outside of my door. We were economically diverse and we were racially diverse, so I thought of my audience or I think of my audience as those folks who still live on my block.

Kai Wright: Wow. I understand Second Stage is doing some things in terms of the audience to make sure that this play then is accessible to both currently incarcerated and formerly incarcerated folks. Is that right?

Lynn Nottage: Yes. We have this wonderful partnership with Art for Justice, because one of the things that was really super important to me is that we reach the community that the play is directly about. I didn't want it to feel distant and remote. I wanted the folks who are actually going through some of the struggles that the folks on the stage are experiencing to be in the audience. We've been able to invite people in throughout the run of the show. Folks are really responding and feel that the work is actually quite truthful. The play is definitely resonated with the formerly incarcerated. One of the other things that we endeavor to do because we have this opportunity to livestream is to take it to the prisons.

Kai Wright: Wow. I can imagine Broadway theater brought to a prison via livestream. That's a wonderful thing.

Lynn Nottage: I'm so excited. If we do anything throughout this run, that's one of the things I'm going to be most proud of, is being able to reach a new audience that's literally shut in.

Kai Wright: Uzo Aduba is a revelation in this show in Clyde's to me. She manages to be almost a caricature of an abusive boss on one hand while simultaneously lovable to the audience, and having a bit of mystery to her. It struck me that she's herself formerly incarcerated, but she's the only one whose backstory you don't fully tell. What were you up to with her?

Lynn Nottage: I really was thinking of-- the character's called Clyde, and she is seductively wicked is how I like to think of her, is that we enjoy watching her be bad. In some way, she's the one character that doesn't change at all. She's the character who's completely intractable. For those who are in that liminal space, she represents all of the obstacles that they're going to face when they get out. She's constantly tearing them down and they have to figure out ways to resurrect their spirit. I was interested in her as the mischief maker as Isle was, that person, the gatekeeper

Kai Wright: She's damaged herself.

Lynn Nottage: She has very damaged herself, but she's the one character that's really not willing to do that self-interrogation. In some cases, it's the way in which she survives. I'm very interested in characters who are morally ambiguous. People who on one hand are doing something that is apparently generous. She's giving these folks opportunities where no one else will, but once they have that opportunity, she is cruel. She's exacting and she's punishing. I also think every one of us has had a boss at some point who has in some form or another, tortured us. I think that Clyde is very relatable to a lot of people in the audience.

[music]

Kai Wright: Coming up, Lynn Nottage is among the artists who have been credited with foreshadowing the Trump era, most notably in her Pulitzer Prize-winning play, Sweat. I'll ask her what it was like doing research for that play. Stay tuned.

[music]

Welcome back. I'm Kai Wright, and this is Notes From America. You're listening to a conversation I had with two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright, Lynn Nottage, back in 2021. I spoke to Lynn when she had three shows running in one season, which is a pretty incredible feat. One of those shows, Clyde's, we learn a lesson in a surprising place. We got to talk about the sandwiches. The place is a sandwich shop, and the workers have this unreal reverence for making the perfect sandwich. I don't really even have a smart question about it, Lynn. What is with the adoration of sandwiches here?

Lynn Nottage: I was trying to find the perfect metaphor for creativity. For how people reconstitute their lives. The sandwich, I don't know why or how it came to me, but it's something that I love, and food is the one thing that we can all unite around regardless of where we are. I began thinking of the sandwich really as a way in which people can reinvent themselves. The great thing about the sandwich, and I think it's something that is said in the play, is that it's one of the few things in which you can combine relatively ordinary ingredients and have this extraordinary culinary outcome.

Kai Wright: In some ways the metaphor worked for me too. The experience of watching the show, I felt like I didn't really fully appreciate it until the last bite until the sandwich was fully built, I suppose.

Lynn Nottage: Oh, it's lovely. When you think, you just think about savory and sweet, and dissonant, and harmonious, and that the sandwich really can be all of those things is that you can have a grilled cheese sandwich and you can put some chutney on it and a slice of bacon, and suddenly you have a small piece of heaven.

Kai Wright: Ultimately, I couldn't figure out whether it was a hopeful story or a dreadfully bleak one at the end, and without giving away details, I'm still not sure where I landed emotionally on that. What about you? Is it a hopeful or pessimistic story?

Lynn Nottage: I think it's an open-ended. I really invite the audience to be the final collaborator and take away what they will. There's some people who leave and see it as being incredibly healing and optimistic, and hopeful, and there are other people who leave and think, oh my God, the cycle is just going to continue. I really think it's where one is in their life determines what ending they take away.

Kai Wright: I suppose that says something about where I'm in my-- [laughs]

Lynn Nottage: You know where you're glass half full or a glass half empty kind of person.

[music]

Kai Wright: Clyde's was based on research. Lynn Nottage did in Reading, Pennsylvania, a Rust Belt town that has experienced a great deal of pain with the end of the manufacturing economy. That research also informed her earlier play, Sweat, for which she won one of her two Pulitzers. Sweat debuted in 2015 and made it to Broadway two years later. By that point, the story felt prescient. You're thinking a lot about working people and the cross-currents of race and gender within this particular class of people, a group that has always been fetishized in all these weird ways in American politics. I think it's rightly been said that Sweat foreshadowed the Trump era in that regard. Was that on your mind when you wrote it?

Lynn Nottage: Oh, I actually get asked that question a lot. I could never have foreseen Trump coming. I don't think any of us in our wildest of imagination could have imagined that we would've had four years with Donald Trump as president. What I did see when I was doing a lot of the interviews in the Rust Belt was the level of disaffection, particularly from working-class white people who felt like the American dream was slowly slipping between their fingers. Rather than interrogating their own practices and thinking about how they were contributing to their own downfall, they were pointing fingers and beginning to blame others. I thought that their disaffection was beginning to metastasize and turn dark and ugly.

Kai Wright: What was that owing to that you were observing in people? How would you diagnose it?

Lynn Nottage: I can tell you very directly how I would diagnose it, is that one of the questions that I always asked when I was in Reading, Pennsylvania is, how would you describe your town now? People would inevitably say, "Reading was", and I thought, oh, we have a really big problem because we have a group of people who can't imagine themself in present tense and in future tense, is that they're always looking backward. There's a line in Sweat which a character named Stan says, is Nostalgia is a disease and it's slowly eating away at us. I think that what I found is a lot of people are holding on to American ideals that no longer existed or didn't ever really exist.

Kai Wright: Lynn's new show, Clyde's, is a bit of a follow-up to this conversation she began out of her research in Reading, because one character, he's actually the only white character in the show, is someone who we first met on stage in Sweat.

Lynn Nottage: They have one character named Jason, who is the most unresolved character in Sweat when the play ended. I felt like there were still things that I want to investigate with his character. He somehow wandered into this particular play and he stayed. He is the outlier in Clyde's. He enters the play in the third scene and he's somewhat of a disruptor. In Sweat he commits a very heinous hate crime.

The question is whether someone who has done that can actually be forgiven. I think that when he enters the sandwich shop, he enters with a great deal of shame. I was just interested in how that moves through his body and whether someone like that really can find a new way through the world and be transformed. Is he going to be able to get out of that space or is he perpetually going to be trapped?

Kai Wright: He was such a powerful character.

Lynn Nottage: Yes.

Kai Wright: It's really interesting to think about then if you're saying that as you talk to people to develop Sweat, You heard all of this past tense, people who couldn't think of themselves in present tense, and then Clyde's is so about imagining a future.

Lynn Nottage: Right. I just felt, at least on a very personal level after dwelling in the world of Sweat, which is dark and it's not optimistic, that I personally needed to go someplace where I felt hope, where I felt that the characters who were experiencing real hardships had the opportunity to transcend and to forge community, and to touch something that was beautiful. In this case, it is a sandwich. For me, on a very personal level as an artist, I felt that I needed to share at least my hope and my optimism with audiences and hope that in some ways they would respond to it and be in conversation with what I was writing.

Kai Wright: Why this interest in class in this way? You really, as an artist, are spending a lot of time in this space of where class and race, and gender come together. Why is that something you're drawn to, you think?

Lynn Nottage: It's interesting, because I recently had a revelation about this, because I was like, why am I so interested? Why do I constantly want to tell stories about working people? Number one, I'm a working person. I don't think that folks often think of artists as working people. We're folks who've experienced a lot of economic hardship and we work very hard for very little reward. There's a real connection between what we do as artists, craftspeople, and folks who are working in factories and working for a minimum wage. We understand that.

That's just the bottom line. I recall when I was growing up, we had some hardship in my life and our circumstances changed very, very quickly. I watched my mother who was this incredible woman having to work 24/7. She'd get up at 6:00 in the morning, she'd be out the door, and she didn't finish working until nine and ten o'clock at night. That, as a child, really makes an imprint. I think I wanted to tell her story and the story of my grandparents and the people who I encountered who were working people. I thought, I don't see those stories that often, and I don't see the people like my family drawn in ways that are three-dimensional and compassionate.

Kai Wright: You grew up in Boerum Hill in Brooklyn. You said earlier that's where that family was. If I'm not mistaken, you attended the High School of Music & Art, right?

Lynn Nottage: Yes, I did.

Kai Wright: A true New York local. What's your relationship to the city? True New York locals have quite a relationship to the history of this city. What about yourself?

Lynn Nottage: I love this city. I feel sometimes like a small town girl because I haven't for any length of time lived anywhere else. I actually live in the house that I grew up in. I think that the city is just my lifeblood. I love the complexity of it. I love the diversity of it. I love that there are arts that are so accessible and that every single day I get on the subway, there's something that happens that blows my mind.

Kai Wright: Do you remember when you first decided, I want to turn to the arts, I have things to say that I can only say through art?

Lynn Nottage: I was really fortunate to have parents, from the time I was very young, who were deeply invested in the arts. If you come to my home, there were always incredible works of art that were on the walls. They took me to see the theater and they took me to see music when I was very young. I just had this really delicious moment when I was watching Summer of Soul, that documentary that Questlove made. In one of the first few frames, I saw my mother in the crowd enjoying music, and I thought that's who she was and that's who [crosstalk]--

Kai Wright: Wait, literally?

Lynn Nottage: Literally.

Kai Wright: Oh, wow.

Lynn Nottage: It was really, really cool. I haven't seen my mother in motion in 24 years. It was just like this Easter egg. It was this wonderful thing. Seeing her just reminded me of what they gave me. You talk about living in the city, and what they did is they gave me the city. I grew up at a time when as kids we were like free-range chickens. You opened up the doors and you just went outside.

You didn't come back in until the street lamps were on. We explored. Thankfully we weren't just playing out in the street, which is what we did, but we went to movie theaters. We went to the theater. We went and we heard music in the park. There was this kind of vibrancy that I wanted to keep alive for the rest of my life. I think that's why I make art and that's why I make theater.

Kai Wright: You had that background. You went on and got degrees in Brown and Yale Drama School. Then you got a job at Amnesty International after school. I wonder was that just one of those out-of-school jobs or does that tell us something about the foundation of your work?

Lynn Nottage: No, I think I got that job for very intentional reasons. When I was at the Yale School of Drama, it was during a very difficult moment in our country. It was the height of the AIDS epidemic. It was the height of the crack epidemic. I was watching classmates die not only from AIDS but from drug addiction. Suddenly the notion of writing a play felt very decadent to me. I really thought, I have to do something. I have to be in conversation with this culture in some other way. It was really a struggle for me to figure out how as an artist I could affect any kind of change. I deliberately looked for a job where I could do something that felt tangible.

I began working at Amnesty International as the press officer during a key moment in human rights history. I look at those years that I was there as my second graduate school experience. I was there when Nelson Mandela walked out of prison, which was an extraordinary moment. I was there when the Berlin Wall came down. I was there when the Guilford Four got out of prison. It felt as though human rights work was really doing. One of the things that we did when I was at Amnesty is really introduce the notion of human rights as the language of Detton. Prior to that, when presidents and prime ministers sat down, human rights wasn't necessarily something that was placed on the table as an issue.

Kai Wright: Certainly that background makes me think of your show, Ruined, which you won your first Pulitzer Prize for in 2009. It's set in the Democratic Republic of Congo among a group of women who are trying to survive the ravages of war including rape. Again, not exactly an easy setup for a night at the theater, but ultimately I see it. Others have said it's a story of resilience. I guess I just want to prompt you to talk about that, this idea of human resilience in your work, in that show in particular.

Lynn Nottage: 2004, 2005, when the war in Democratic Republic was raging as we know, that war ended up taking like 6.5 million lives. It was the largest armed conflict since World War II, and yet it was not really registering with people outside of Africa. I went with director Kate Whoriskey and my husband to East Africa and began interviewing women who were fleeing that are in conflict. One of the things that we found is that all of them had been raped and had been abused. It was something that I wasn't necessarily reading in the newspapers. I thought this is a story that I want to tell.

Originally, we had gone there to do a modern adaptation of Mother Courage, which is Bertolt Brecht's play, but when we began interviewing women and hearing their stories, we realized that there was a story that was unique to Africa. To answer your question, I would sit with some of these women and they tell me stories which were absolutely heartbreaking about what they went through. What I really clung to was the way in which they were able to find hope and optimism and smile. I saw embedded in their stories is this incredible resilience. One of the questions that I used to always ask them is, what do you think of when you think of the words "mother courage"?

They'd say, yes, mother courage. They'd hold those words in their mouths and repeat them. I thought, yes, that's the story I'm telling, is about mother courage, is about resilience. I went home and I wrote Ruined. I know a lot of the critics asked, why do I end the play which is about something that's so dark, which is gender-specific human rights abuses with optimism? I thought, because that's what I experienced, is that no matter what these women went through, they had mother courage, is that they were going to persevere and they were going to resurrect their lives in beautiful ways.

Kai Wright: It's so interesting because that was the truth, because optimism is actually the truth which is so hard to wrap your head around in today's world.

Lynn Nottage: Yes, absolutely. I think just the experiences of us as Black folks in America over the last 400 years. What we have is this incredible ability to reach for optimism, and we're incredibly resilient. I think that's not recognized enough.

Kai Wright: It's really not. I often say easily the most optimistic forward-looking progressive people in this country are Black people and immigrants. For all the talk about we are supposed to be victims, we are easily the biggest believers in a better future.

Lynn Nottage: Amen to that. It's so true. I want to explore that more deeply.

Kai Wright: Thank you so much, not only for this time but just for all your work and your contribution to theater.

Lynn Nottage: Thank you so much, Kai. I listen to show and I really love your show. I'm super, super delighted to be here with you.

[music]

Kai Wright: That was my conversation with playwright Lynn Nottage from 2021. Up next, we'll stay in the theater world with another artist who has made some waves on Broadway. David Byrne. We revisit my conversation with him from 2022 about his musical American Utopia and the challenges of human connection.

[MUSIC - David Byrne:Slippery People]

Kai Wright: It's Notes for America. I'm Kai Wright. We're going to revisit a conversation I had with artist, David Byrne, back in 2022. This is his song, Slippery People, which he originally wrote with his band, Talking Heads. It's a song that evokes thoughts about faith, not just about religion, that's in there too, but I mean faith like faith we put in people, in each other, about how we all try to navigate the challenges of our lives together.

That might be why this song is a good fit for Byrne's show, American Utopia. It's a live Broadway show in which he performs his music, almost as a catalyst to a wider conversation about living in a plural society, you, me, us, and what's possible, if we can make that work. I was lucky enough to talk to David Byrne about his music, about the show, and about the musical democracy that is on his mind. David, thank you so much for this time.

David Byrne: Thank you. Thank you for arranging this.

Kai Wright: I want to start with, you spoke with a friend of mine, actually Rich Benjamin for The New Yorker, and you said something to him that really stuck with me. You were talking about the love that you feel coming from the audience while performing American Utopia. You said, though, that you try not to take it personally because you know it's not really about you, but you also nonetheless, try to reciprocate it in the moment.

I have to say that almost made me cry because while it's really beautiful to me, it also sounds like a lonely thing to experience. I bring that up because it just reminds me of how I felt watching the show in general and your work in general of having these overlapping, often conflicting emotions. I don't know, I just want to start with asking you to say more about that feeling you described around love.

David Byrne: Like a lot of whether it's actors or musicians, performers in general, we as audience members, we confuse that person's work with the real person. To a large extent, it's the work that they love that is affecting them. I'm the delivery service for that. Okay, maybe I'm doing a pretty good job of it, but I also feel like there is a little bit of a difference between the work and what that means to people and me as a person.

Kai Wright: American Utopia in general seems to me to be interested in the contradictions and challenges, and joys of being social creatures. That's a lot of what I take from it, craving connections as humans in the complications of that, is that right?

David Byrne: Yes. A lot of us, it's the journey of this person embodied by me and based on a lot of my own experiences, from being socially awkward, and gradually over decades, finding oneself in a little community where you feel comfortable. In my case, that might be a band, and then gradually becoming comfortable enough that you can engage with strangers, and also become socially engaged, socially active in terms of issues and things like that. For me, anyway, I find that that's a step-by-step project. The show starts with me holding a brain.

[MUSIC - David Byrne:Here]

So it's I'm living inside my head. Then by the end of the show, we're talking about the whole society.

Kai Wright: Along those lines, when you introduce the song, Everybody's Coming to My House.

[MUSIC - David Byrne:Everybody's Coming To My House]

You say in the show that when people cover it, it comes off as this happy celebration, but for you, it was all about anxiety that everybody's coming to my house. Tell me about that. It's interesting, even that you notice the difference.

David Byrne: Yes, we invited a high school choir in Detroit, to cover the song, to do an interpretation of it.

[MUSIC - David Byrne:Everybody's Coming To My House]

I don't know exactly what they did, but the feeling I got from their song was very different from the feeling I got from my recording of it. In my recording, you could sense that this is a guy who's a little bit apprehensive about having to deal with socially with a whole bunch of people. Whereas these kids when they did it, they couldn't wait to have a bunch of people over. They were just welcoming everyone and inviting them to come over. I thought that was wonderful, and maybe I can learn something from this.

Kai Wright: The show grew out of your 2018 album. Obviously it was conceived before we all experienced a lot of the hard stuff that complicates our American utopia, as it were now; COVID, the near collapse of democracy, the reaction to George Floyd's murder. What were you seeing in our lives that did creep into this show as you were conceiving it back, because it's not a literal statement about utopia in America.

David Byrne: No, it's not that, and it's not to be taken that way. You hear this saying that we live in a Utopia, or me giving prescriptive directions like, this is what we need to do. We touch on immigration, we touch on race, we touch on voting, we touch on a lot of subjects that have since then become the main focus of our lives in some ways, but it was definitely in the air already. As with a lot of things, the pandemic just threw things into bigger relief. It was more the tour.

When I started thinking about how to perform this material, and mixing some older material, I became very concerned with what I saw happening in the world, in the country that I live in. I thought I need to at least acknowledge that. I'm not going to provide everybody with a lot of answers, but you have to acknowledge what's going on in the world that we live in, and not only provide an entertainment, although that's kind of have to do that too, otherwise people are just going to walk out.

Kai Wright: It is ultimately quite a joyful celebration. That's the experience of it, at least watching it, people literally dance in the aisles. I watched it, I watched the HBO version, which was directed by Spike Lee. My boyfriend and I danced on the couch instead of in the aisles. The film version really does still capture how much fun the audience appears to be having throughout the show. How important was that to the experience as a whole?

David Byrne: I thought it was very important that people experienced that utopia that we're talking about, just a little bit. They just get a little taste of it, whether it's dancing or the joy that I see in the audience. A lot of what the show does is not prescriptive or descriptive. It's not me telling people, this is what's going on, this is what I see and this is what we should do. I want them to witness it. I want them to witness what's possible. That's, to me, what a lot of the show is about. They see what we can be. Granted it's just a show, but it's still very affirmative that way.

Kai Wright: Along those lines, I'm struck by the mobility of the performance. For anyone who hasn't seen the show, all the musicians including the drummers are equipped to walk and move freely anywhere on the stage as they play. How did that format then shape what you were trying to achieve?

David Byrne: That was something I'd been building to for many years. I myself had gone wireless for a while, and then on a tour that I did with St. Vincent, we had a brass section, and the brass section was completely mobile and wireless. I just thought, can we take this further? Can we have everybody, even the drummers, keyboard player, can we have everybody mobile? When we did that, these other things happen. One thing is that the stage becomes more democratic.

The drummers can come to the front. They're not relegated to a platform in the back. They can be in the front, and I'm in the back. We're constantly in motion so that everybody's at the front at some point. That's a big thing. The other thing is that by eliminating all the stuff that's on stage, it really does become about the people, how they relate to one another and how they relate to the audience. It's not about special effects and video screens, and all the other stuff that we often use in shows.

Kai Wright: It's stripped out. Again, for people who haven't seen it, the set is also quite stripped down. Gray suits, gray background, without shoes. All of that I gather then is about this point of it's us as humans together.

David Byrne: Yes. If we take everything away, all that's left is us.

[music]

Kai Wright: It's a large company of musicians. It must be said that it seems like an intentionally kaleidoscopic company to me in terms of race and gender, and background, but also styles and instruments, and roles, and it's a beautiful chaos on the stage. I have to assume that is also intentional.

David Byrne: Yes. Obviously we want to show the diversity that exists in this country. That isn't always represented on stage, but it's there. The talent is out there. A lot of the musicians I work with, we'll take the drummers. The drummers, in order to get all these different sounds like what we'd have on recordings, they started bringing in Afro Latin instruments and Brazilian instruments, and all kinds of stuff. There's a real drum and percussion symphony going on back there to achieve all these sounds.

[music]

Kai Wright: Now that having heard you talk about the democracy of the stage, it's also a democracy of sound, it feels like, that there's moments where it's almost cacophonous.

David Byrne: We tend to see it as being very organized, but yes, there's a lot of grooves going on.

Kai Wright: Toward the end of the show, you cover Janelle Monáe's protest song, Hell You Talmbout.

[MUSIC - David Byrne:Hell You Talmbout]

Why'd you choose to include that?

David Byrne: We included that in the tour before we did the Broadway show. I felt like as an artist, as a human being, we have to reflect the world that we live in. Although we want to be entertaining, we want to also reflect what's happening around us.

[MUSIC - David Byrne:Hell You Talmbout]

I heard that song a little bit before that and just thought it was very moving and beautiful in that it doesn't tell you what to do, it just tells you this happened, don't forget these people. These are all human beings whose lives have been taken. I thought that that was a beautiful way of putting that forward. She liked the idea that we were doing it. That meant a lot. We just kept doing that when we moved to Broadway.

Kai Wright: It's followed by One Fine Day, the song, One Fine Day which is just this gorgeous coral rendition.

[MUSIC - David Byrne:One Fine Day]

Part of me, David, wanted to reject that song, if I'm honest. It was too beautiful and too hopeful of a response, but of course I couldn't because it is so beautiful and it is so hopeful. I just wonder how you reacted to my experience with that.

David Byrne: We had exactly the same experience when we were on tour. We would do Hell You Talmbout as an encore number, and we couldn't follow it with anything. We felt like, no, we can't follow this with anything else. We're going to leave people with this. Then for Broadway we thought, no, let's experiment and see if we can leave people on a slightly more hopeful note. We present them with reality, but then offer them the idea that we can actually move on from this. We can be better than this.

We tried a whole bunch of different endings. We did out-of-town tryouts in Boston, and I think we had three different endings for the show, and that's the one we ended up with. It does take away some of the punch that you've received, the punch in the gut you've received from Hell You, but it also gives you the sense that no, we can actually do something. This is not impossible. There is actually possibility that we can actually move on from this.

Kai Wright: We talk a lot on this show editorially on our team about not leading people down dark alleys, and leaving them there, given the stuff that we cover so often, and it sounds like a similar conversation.

David Byrne: That's a really good way of putting it. You want to let people see the dark alley, but you don't probably want to leave them there.

Kai Wright: At least the version that I saw you, the encore does become the classic talking heads song, Road to Nowhere.

[MUSIC - David Byrne:Road to Nowhere]

Maybe that's just a crowd pleasing encore, but I'm guessing not from the way you think about your work. Why did you decide to end a show called American Utopia with a song called Road to Nowhere?

David Byrne: [laughs] It is a crowd-pleaser. Despite the title and the lyrics it's actually very uplifting. That's one of those songs that does that where what it says and how it makes you feel is a contradiction.

[MUSIC - David Byrne:Road to Nowhere]

Kai Wright: This is what I said at the beginning. Honestly, for me, that's almost definitive of your music in general. Is that a fair take?

David Byrne: Yes, it happens occasionally. I love that about music. It can hold contradictions like that, or it can hold different feelings and ideas. At the same time, I've often felt that in a lot of Latin music, for example, the lyrics can be really sad, very melancholy and tragic, but the music is giving you hope. It doesn't say anything in words, but it gives the singer and the listener hope. You have these two different things in balance, trying to achieve a balance between each other. I thought music can do that. You can't do that in too many forms.

Kai Wright: Does that song-- how does the meaning feel now compared to when you first wrote it?

David Byrne: It has stayed as being uplifting despite what it says. If we took it literally, people would think, oh, he thinks we're in a hopeless situation, climate change, everything else. We're just going to hell in the hand basket. He's just saying, it's been a nice ride. Here we go. We're all going down with the ship here. I don't think that's what comes across, but as I said, that's what music can do.

[music]

Kai Wright: That was my conversation with David Byrne in 2022. If you missed the Broadway run of his show, American Utopia, you can catch a filmed version directed by Spike Lee on Max. Notes from America is a production of WNYC studios. Follow us wherever you get your podcasts and @noteswithkai on Instagram. Theme music and sound design by Jared Paul. Matthew Mirando is our live engineer. Our team also includes Regina de Heer, Karen Frillmann, Suzanne Gaber, Rahima Nasa, David Norville, and Lindsay Foster Thomas. Our executive producer is Andre Robert Lee, and I am Kai Wright. Thank you so much for joining us.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.