A (Long) History of American Drug Panics

( (Food and Drug Administration / Wikipedia) / Wikimedia Commons )

BOB GARFIELD: This is On the Media. I’m Bob Garfield.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And I’m Brooke Gladstone. The template for the drug war, established by Harry Anslinger in the ‘30s, would play out again and again. Similar stereotypes, enabled by the same breathless media coverage, would power the political discourse around crack cocaine, meth and heroin for years to come. After Richard Nixon, nearly every president would spend more on law enforcement than drug treatment and see prison populations surge. In fact, you could fix the date of our modern war on drugs to Nixon's declaration in 1971.

[CLIP]:

PRESIDENT RICHARD NIXON: America’s public enemy number one in the United States is drug abuse. In order to fight and defeat this enemy, it is necessary to wage a new all-out offensive.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Nixon’s domestic affairs advisor, John Ehrlichman, would later admit to journalist Dan Baum that the president’s position on drugs was a hit job. Quote, “By getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities,” Ehrlichman said. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course, we did.

CRAIG REINARMAN: Because he was trying to signal he was going to stop all the mass demonstrations that were going on, all the insurrections in the inner cities, he was pretty clear that the way to do that would be to come down hard on drugs.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: That’s Craig Reinarman, author of Crack in America: Demon Drugs and Social Justice. And so, Nixon signed the comprehensive Drug Control Act of 1970, which outlined the five-schedule legal classification of drugs we use today.

CRAIG REINARMAN: You had marijuana in Schedule I, which is the most severe category where there’s no accepted medical use and no level of safe use. And, of course, that wasn't true about marijuana. It wasn’t true about LSD, for that matter, either. Amphetamine and the benzodiazepines like Valium and its chemical cousins were treated lightly because they were very widely prescribed at that point. It was a huge winner for the pharmaceutical companies.

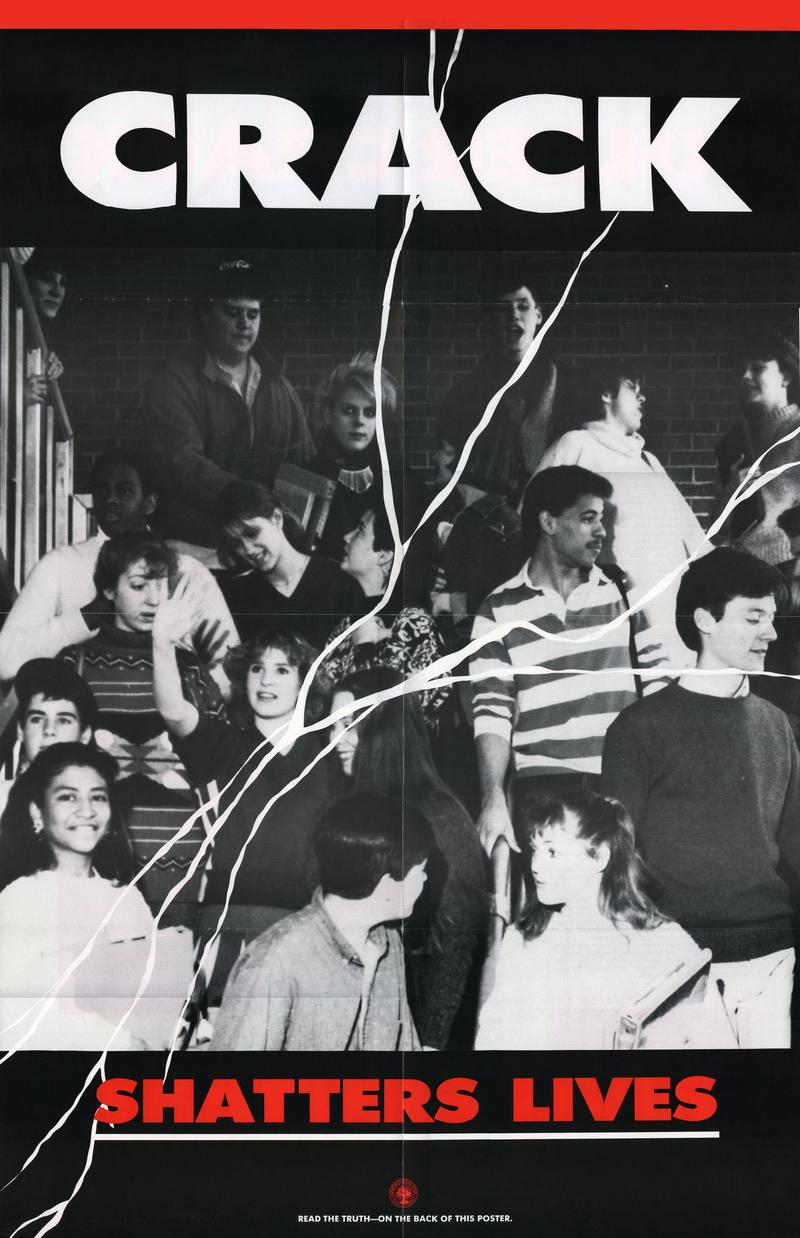

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So let's jump to the mid-‘80s. You say this was a period characterized by antidrug extremism, all centered on crack, launched by the typical media coverage of drugs, magnification of the extreme.

CRAIG REINARMAN: Right, you take the most extreme case because it's the most dramatic. In 1986, Len Bias, this all-American basketball player, destined for a great pro career with the Boston Celtics, we’re told that he died of a crack overdose. So if this is a drug that can kill instantly a great athlete, surely all of our children are at risk. Well, it turns out he never took crack. He drank 7 grams of cocaine in a soft drink and died of an overdose. But that set things in motion.

All three major television networks did shows within a month or so of each other, in ’86. The first was “48 Hours on Crack Street,” and you had Dan Rather reporting in a very dramatic way.

[CLIPS]:

DAN RATHER: This is the typical tiny bottle for the new illegal drug of choice in America, crack. Vials like this one are turning up empty and discarded in the streets, in the parks, in the schoolyards around the nation, and many of the people who use crack are turning up with blown minds and blown bank accounts and worse.

CRAIG REINARMAN: And not to be outdone, NBC did one called, “Cocaine Country.”

TOM BROKAW: Cocaine Country is not any one city, not any one generation or ethnic community. The plain fact is it's almost everywhere these days. Crack is probably the fastest-growing drug menace and also the scariest.

CRAIG REINARMAN: Followed quickly by ABC doing one.

PETER JENNINGS: These are the images that cocaine brings to mind, a drug that causes death and devastation and reduces its victims to a whimpering animal-like state.

CRAIG REINARMAN: Crack was unknown, unheard of. In only three or four major cities did you have any experience with it at all. By the time those three shows were done within the course of a month, about 100 million Americans knew what it was and knew that it’s something about a full-body orgasm.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Newsweek around the time quoted a drug expert who said that crack is “the most addictive drug known to man.”

CRAIG REINARMAN: Yeah, this was a claim made before about certain forms of distilled spirits. It was made with regard to morphine. It was made with regard to heroin. And it’s been made since about meth.

Myth number one was that it was new, and it wasn’t. It was a marketing innovation because usually you’d get cocaine, it would cost a $100 to get a gram of powder. Crack was sold in base form in $5 and $10 units. And so, it meant that a whole new market segment, meaning poor people in the inner cities, could get the most intense rush they've ever experienced for five or ten dollars.

Another myth was that it was spreading to all segments of the population. It turns out that was sheer nonsense. It never spread very far outside of the most vulnerable parts of the population. But these were communities that were already reeling from severe unemployment, cuts in social services. I remember now where six years into the Reagan administration, it was systematically dismantling almost all the programs that made even a little bit of difference in the lives of poor people.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: In fact, cocaine use had quadrupled a decade earlier. In the ‘70s, people were freebasing it, which is essentially the same as smoking crack, and yet, there wasn't a cocaine scare of this sort in the ‘70s. There weren’t myths about cocaine babies.

CRAIG REINARMAN: That’s right but this was mostly among professional athletes, rock stars, Wall Street wizards. When it starts to spread to the inner city, as William Bennett put it, “we want to make sure that they know that there's a prison cell waiting for them.”

BROOKE GLADSTONE: [LAUGHS] Hence, Reagan's 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act.

[CLIP]:

PRESIDENT RONALD REAGAN: Today, there is a new epidemic, smokeable cocaine, otherwise known as crack. It is an explosively destructive and often lethal substance, which is crushing its users. It is an uncontrolled fire.

[END CLIP]

CRAIG REINARMAN: And that gave five-year mandatory minimum sentences for tiny amounts of crack that you could hide in a matchbook, if you had 50 grams, a still very small amount, a 10- year mandatory minimum. If you happened to have a prior felony drug conviction, you’d get 20 years to life for having small amounts. It eliminated parole. It terminated tenancy in public housing if anybody in a tenant’s household or any guest sold drugs near public housing. So the results, quite predictably, were mass incarceration, disproportionately, of black people and Latinos.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So Reagan's Act was passed in 1986. You jump ahead to 1989. George H. W. Bush holds up a bag of crack during a prime time national TV address from the Oval Office.

[CLIP]:

PRESIDENT GEORGE H. W. BUSH: This, this is crack cocaine seized a few days ago by drug enforcement agents in a park just across the street from the White House. It could easily have been heroin or PCP. It's as innocent looking as candy, but it's turning our cities into battle zones.

[END CLIP]

CRAIG REINARMAN: A very interesting story behind that bag of crack that he held up. It originated in the mind of a speechwriter. But, of course, it turns out there was no crack being sold or used in the park right across the street from the White House and so, they had to make it happen. So they made several calls, from the top of the administration's chief of staff on down. And then they had to lure a young teenage dealer to Lafayette Park across the street from the White House, and he had to be given directions how to get there because he’d never been there.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So did public opinion change after George H. W. Bush's speech?

CRAIG REINARMAN: Oh yeah. The number of people who in public opinion polls would say that drugs are, you know, the number-one problem, the most important problem that we have to deal with skyrocketed, beginning in ’86, going through ’88, ‘89.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And yet, a year after Bush's speech the same magazine that five years earlier had called cocaine “the most addictive drug known to man,” Newsweek wrote, “Don’t tell the kids but there's a dirty little secret about crack. As with most other drugs, a lot of people use it without getting addicted. In their zeal to shield young people from the plague of drugs, the media and many drug educators have hyped instant and total addiction.”

CRAIG REINARMAN: That's right. I give them credit for a course correction there. And the Washington Post, by 1988, ’89, they talked about a “hyperbole epidemic.” The New York Times phrase was “overdosed on oratory” and that the idea that there was such a thing as a crack baby, the minute they did the epidemiological research, they discovered it was not true. Crack babies, it turns out, couldn't be distinguished from other babies who grew up in great poverty.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: I still can't quite understand why being tough on drugs became a political necessity in America. When Clinton came in, in 1994, he signed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act. That was the infamous “three strikes rule.” So why?

CRAIG REINARMAN: Clinton had a strategy to steal the thunder of the right. You got to remember that local governments were very hard pressed and in fiscal crisis because of all the cuts under Reagan and Bush, so Clinton starts a new stream of federal funding to local law enforcement. And the only criteria used to determine whether they would deserve more funding was, did you make a drug arrest, not distinguishing between some kid on a street corner who’s got a joint and a kingpin controlling big sales. So you saw skyrocketing under Clinton of marijuana arrests. Ninety percent of them were for possession, alone. You have a criminal record. You’re stigmatized when it comes to housing and employment, thereafter. And so, there's a way in which you could understand low-level marijuana arrests as a kind of “head start” for prison.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Obviously, we have to talk about meth. We were told that it was the most addictive drug, ever.

[CLIPS]:

MAN: Speed, crack, crystal, by any name, meth is today the most talked about drug in America.

WOMAN: It eats away not only at your teeth but every bone, your eyes. It, it kills you.

MAN: From my experience, crystal meth is the most dangerous drug. It is the most addictive.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Was this just a replay of the crack scare?

CRAIG REINARMAN: And other earlier drug scares, to be sure. Methamphetamine, when it — particularly when it is injected or smoked, again, you get a very intense rush, and there are people who go on these binges. But these were people, by and large, who were from small dying agricultural towns across the Midwest. There was no real national epidemic but towns would be devastated, small cities. What gets lost is the ordinary controlled users, the long-distance truckers who use amphetamine to survive, or the professionals who go to their shrink and they get a prescription because you have adult-onset ADHD.

But the kind of stereotype that we get is somebody who had long dirty hair, razor thin, teeth destroyed. This became the kind of iconic figure of the meth epidemic. These were people who were already with their toes up on the edge of the abyss, and then this powerful drug comes along and pushes them over the edge.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: A couple of years ago, you wrote that, quote, “Opiate addiction is on a rampage, from OxyContin to heroin. Overdoses have quadrupled since 2000 and are now the leading cause of injury-related death.” And you said, “If asked to design headlines to fuel the war on drugs, one could hardly do better.” So why is public support for the drug war at its lowest in decades?

CRAIG REINARMAN: We really have figured out now, after watching prison populations soar, that we’re not gonna incarcerate our way out of our drug problems. We’ve had more or less incessant drug war since Nixon openly declared it in 1971. Still, we have these problems. And, at the same time, you have medical science saying, wait a minute, this is not an issue of deviant behavior and it’s better framed and understood as a health issue.

And so, the consensus has fractured. It’s not clear what's gonna take its place but you’re seeing more and more harm reduction policies, like syringe exchanges, so that you can stop the spread of AIDS. You have all kinds of medical marijuana across the United States and a variety of other policy experiments that are not really about lock ‘em up and throw away the key.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Craig, thank you very much.

CRAIG REINARMAN: Brooke, it's a pleasure. Thank you.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Craig Reinarman is a professor emeritus of Sociology and Legal Studies at the University of California, Santa Cruz.