When Opera Meets Autism

( Meghan Cunnane )

MH: I’m in the studio here with our reporter, and Amanda Aronczyk, you brought a recording to play for me.

AA: Yeah, that’s right. And before I play it for you, let me kind of set the scene: Picture a bunch of kids in their teenagers, people maybe early twenties, and they are sitting around in a circle. It's a group therapy session for high-functioning kids on the autism spectrum.

MH: Okay.

AA: They’re working on their social skills, so they’re talking about a book that one of them is writing. In that book there's a wedding scene. And this one kid, who we’re calling Devon, has a question.

DEVON: How about...your friends...how about friends… how about you drive your…. How about you, actually are there any bridesmaids at the wedding?

MH: What’s up with all the laughing?

AA: Well, these guys have all known each other for a long time, so I think it’s pretty good natured laughing. They can all just tell that Devon is having a really hard time getting that question out.

MH: He keeps just saying: how about, how about, how about.

AA: Yeah, he gets stuck.

MH: Yeah.

AA: The researcher who sent this to me, her name is Dr. Michelle Dunn. For years she’s known that this a problem for her patients.

She’s a neuropsychologist and she runs the Montefiore Einstein Center for Autism and Communication Disorders, which is in New York. The patients she sees are high functioning people. So they’re very bright, but they might still have difficulties just talking.

MICHELLE DUNN: We had these kids who had these odd sounding voices or they were not projecting when they spoke or they were just doing strange things with their voices that weren’t working for them in the world.

AA: So Dr Dunn suggested all sort of things she learned from her 30 years of working in this field: she would tell her patients to visualize the problem. Or plan what you’re going to say in advance.

MD: I kept telling them, you need to stop and think and then things will come out better. It’s a relatively good idea, but still was not working.

AA: And what’s the problem with saying, stop and think?

MD: The problem was, that they wouldn’t stop. The problem was that a lot of the kids were already impulsive enough that they wouldn’t stop.

AA: The patients she sees are becoming adults, right. And Dr Dunn worries about this transition. She knows they’re about to lose a lot of the services they get as kids. They won't have the therapy and educational support. And they need to go out on their own. They need to go to college. Get jobs. Make friends. And that can be hard if you don’t talk in a way that’s considered normal.

MH: Yeah, people can be a little bit cruel when you sound different.

AA: And I was told that these kinds of speech patterns can be one of the hardest things to change. So Dr. Dunn had really felt like she had run out of options.

Until…this:

[OPERA]

MH: This is Only Human from WNYC, and I’m Mary Harris.

AA: Today on the show an unusual collaboration between an opera singer and an autism researcher.

Dr. Dunn sings in a church choir, and one day she begins chatting with a fellow choir member, a guy named Larry Harris. This is him singing here.

[OPERA]

AA: He’s a big guy, 6’5”, turns out he was an NFL offensive (AW-fen-sive) lineman in the 1970s, for the Houston Oilers.

1970s Football Game Archive: we’re live from the Orange Bowl in Miami… the Houston Oilers against the Miami Dolphins…

AA: The team’s logo was of an oil rig - Ol ‘Riggy the called it. And, true story: during the off-season, Larry Harris worked on an actual oil rig.

MH: Okay, very different times in the NFL if he’s actually having to work in the off-season.

AA: Yes, I guess probably less lucrative back then. The way Larry tells it, he was working on one of these rigs, he’s 300 feet above the Gulf of Mexico, when he has an epiphany. He’d rather be an opera singer.

[Football Crossfades with Opera]

And so you fast forward many years. Larry quits the NFL and becomes an opera singer and he meets Dr. Dunn in choir at church. And this marks the start of his third career.

HARRIS: You know, I-I didn’t get to explore my brain as a football player. Really. And it was a great experience playing in front of millions of people but, I didn’t get to open up my brain the way I am now.

AA: He and Dr Dunn talked about these speech problems her patients were having. And he had all of these ideas based on his background as an athlete and a singer. They started brainstorming together.

MD: After you’ve been in a field for a really long time and you know, you can burn out. But then he comes in here and he’s so excited about everything he sees and he’s got comments and ideas about every single thing we see and do - it’s exciting, it’s fascinating to hear a whole other perspective.

AA: They start making these short lessons that draw from Larry’s training as an opera singer. And they think there is one young man who might really benefit from this. It’s the same guy you heard at the top of the show.

Remember we are calling him Devon, which is not his real name because his family wanted to protect his privacy. Dr. Dunn has known him for a really long time, since he was about 6.

AA: And what was he like as a six year old?

MD: (laughter) He was a maniac! He was such an interesting kid - he was one of those guys who used to talk about his topics incessantly. He was very interested in marine biology at that point - he would get really stuck

AA: And this is really common for people on the spectrum, to become obsessed with one topic.

MD: And one of my goals with him was to teach him how to talk about other people’s topics. So I remember one session, particularly memorable session with him where we were talking about this idea of, ok you’ve talked about marine biology now for a while, and now we’re going to talk about another topic - it’s going to be my topic and, he started screaming at me. “But why, but why do I need to talk about other people’s topics?, I hate other people’s topics! I only like my topics!” this is what was coming out of his mouth. Screaming so loud that his mother came bursting into the room to see if he was okay and if I was okay.

AA: Dr. Dunn says that another common behavior is being inflexible or rigid. Change can be very hard.

AA: And as a kid Devon had a really hard time calming himself down. He couldn’t make friends. He was in special ed classes. As he got older, he was in regular classes, but there was always a teacher there dedicated just to him.

For years he worked on his social skills with Dr. Dunn.

MD: You know, we teach things all the way from how to greet, you know how to say hi, how to take turns, all the way through to - how do you judge how to enter a conversation when there’s a conversation going on? what do you say when you enter the conversation? You know the idea that you have to be thinking, that there’s a topic ongoing so you have to enter on that topic. There’re so many different things, socialization is so complex, but in fact it can be broken down into a lot of rules that can be taught in a social skills group.

AA: By the time Devon was 18, he could talk about other people’s topics. Not just marine biology.

He’s a bright guy – after high school he was recruited by a very good college to do a degree in bioengineering. But at first it did not go well. Remember, this is what he sounded like:

DEVON: How about...And actually our friends...how about...your friends...how about friends… how about you drive your…. How about you, actually are there any bridesmaids at the wedding?

AA: Because he couldn’t get his words out, no one took him seriously. He couldn’t work in a group. He couldn’t make friends. So Dr. Dunn and Larry offered to try out their new technique with him. They worked on it every week.

MD: Okay. So this is after 5 months.

DEVON: I went to this nice Indian restaurant on my birthday. I also went to the metropolitan museum on my birthday.

MD: Okay so.

DEVON: And I had a really good time there!

MD: Can you tell us something about what you saw?

DEVON: I saw - my favorite thing I saw was the European paintings? They told me about - they told me what the paintings symbolized. I once believed that art was only designed to look nice but now I’m realizing that art has a meaning. It’s like incredibly fascinating - actually are there any art fans in here?

MH: (Reacts) He’s like a different person.

AA: I don’t think he is a different person. I think he’s just communicating his ideas clearly.

MH: He’s more presentable person.

AA: Exactly. I think the way he probably spoke before was very off putting.

MH: Yeah.

AA: I was blown away too. Dr Dunn said in her career she’d never seen something work so quickly.

AA: For you, is that a big deal?

MD: Yeah - it’s a very big deal! Putting a person in a place where they can communicate their ideas and their feelings effectively to another human being is incredible! It’s so, it’s had… well you’ll hear what he says about the effect it’s had on him.

AA: But for you? As the person who’s known him since he was a little guy.

MD: Yeah, it’s very exciting. Cause I’ve known all along the kinds of things he’s wanted. You know-sort of, the relationships he’s wanted. He talks now about wanting a girlfriend, you know. He talks about wanting a real friend who really listens to him.

AA: And now she thought these things might be within reach for him.

[MUSIC]

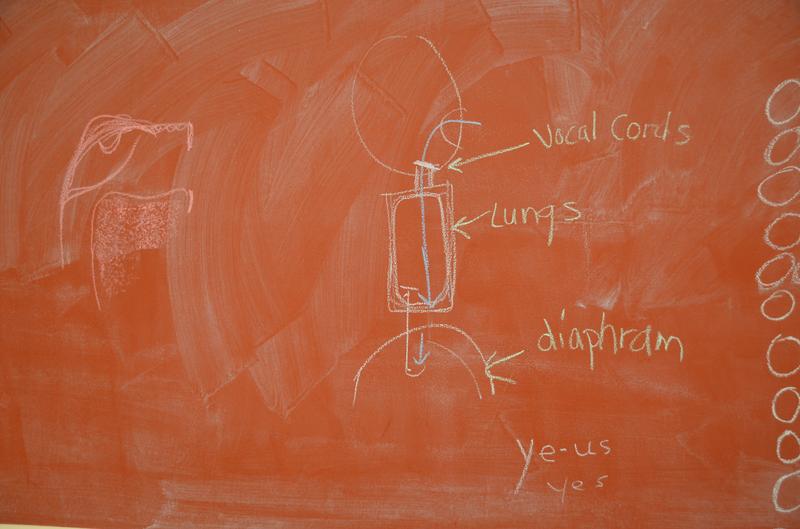

AA: So what were Devon and Larry doing in these hour sessions? Larry was pulling from his opera training.

LH: As an opera singer, you’re not amplified. So you have to project your voice.

AA: To do that you have to be able to control your breath, and to start a sound cleanly. Singers learn to physically feel the opening and closing of their vocal cords.

To show me what it sounds like to sing without fully closing your vocal cords, Larry sang one of Devon’s favorite songs. It’s from the musical “Wicked.”

LH: (sings “For Good” without clean phonation)

AA: And here’s Larry singing the same song while controlling his breath.

L: (sings “for good” from Wicked while doing the breath pause) I’ve heard it said… when people come into our lives for a reason…. (Fades Under)

AA: That “huh” sound forces you to close your vocal cords. They call it “breath pause.”

MUSIC CONTINUES

LH: Okay, that’s enough isn’t it?

AA: Why were you laughing?

DD: Because we should write the words down for him (laughter)

AA: Are those not the words?

DD: Sort of.

LH: Close enough, come on!

AA: Now, Mary, do you want to try making that sound? It’s like a karate chop...

MH: (makes the sound) Huh… Like that?

AA: Now do it again. And this time hold your Adam’s apple, and make the sound again.

MH: Huh.

AA: Do you feel it? (Laugh) You’re supposed to let go.

MH: (Laugh.) It presses down.

AA: Right it presses down. It presses your two vocal cords together.

MH: Okay. So how does this help, though?

AA: Well, Dr. Dunn says they were teaching their patients a physical sensation, that “huh” sound. And that is a cue to slow down.

MD: So it’s just so that they feel the closing of the cords, they feel that the breath has stopped. Then that’s something that helps them to think at that point. But if the breath continues to flow this is what I found, even with all the work telling them stop and think all those kinds of things, if the breath continues to move out, they don’t actually stop and think.

AA: The body tells the brain to pause. If you feel your body stopping, it stops your brain. Because you can’t talk while your breath is paused.

MH: So do you do this in conversation?

AA: Yes. Yes.

MH: You just do it silently?

AA: You do it silently, exactly.

MH: [Gasp.]

AA: Now that I’ve said that to you, you will hear it in the recordings with him. He’s going: Huh.

MH: Really.

AA: As he makes that sound instead of having a thousand words kind of flow out of his mouth, he paused and has to think to kind of think: what am I going to say next? what am I going to say next?

And then what comes out next is more fluent. That’s the idea.

MH: So you basically, stop yourself from talking. Full stop.

AA: Full stop. You close your vocal cords you stop your breath. And it forces you to stop and organize your thoughts.

MH: So has he been able to use it in his everyday life?

AA: Well, that we will get to after the break.

MH: Okay, this is Only Human and I’m Mary Harris.

***********************

[MIDROLL]

Last week I spoke with Peter Grinspoon, a doctor who was addicted to painkillers for years. Eventually he got caught and went to rehab. These days he’s careful about how he writes prescriptions. He tells his kids drugs are evil.

One of our listeners, Jen O’Neal, wrote in to tell us she disagrees. Jen has Ehlers-Danlos [EH-lers Dan-loss] syndrome, which affects the connective tissue between her bones and skin. She’s been through a lot of surgeries and she’s in pain every single day. So she takes painkillers. A lot of them.

Jen says the way we talk about drug addiction means people like her are stigmatized. She writes:

I don’t have any power in the situation between me and my doctor. Especially with chronic pain, when it’s not obvious – they think you’re faking it.

Right now I’m going to school, I need to get home to walk my dog and make dinner. I don’t want to be high. Opioids are not the best thing, they’re just the best we have right now.

Jen tells a lot more of her story at onlyhuman.org. So check it out. And while you’re there, tell us YOUR story.

***********************

MH: I’m Mary Harris and this is Only Human. I’m here with Amanda Aronczyk. And we’re talking about a teenager, we’re calling Devon.

He was the first to try out a new technique, inspired by opera training, it might help people on the autism spectrum speak more effectively.

AA: Yeah and I think now might be a good time to bring up a saying in this field, which is: “if you’ve met one person with autism, you’ve met one person with autism.”

MH: So everyone is different.

AA: Everyone is very different. The spectrum is called a spectrum for a reason. And it’s range is very wide. So what works for Devon, might not necessarily work for someone else.

MH: Sure.

AA: You know how I said before that I wasn’t able to speak with Devon directly?

MH: Yeah, his family wanted to protect his identity.

AA: Mmmhmm. Dr. Dunn was willing to interview him on my behalf. So now I’m going to play you her interview. It was recorded when Devon was 19, about a year after he started trying the technique.

MD: What happens when you try to speak?

DEVON: Stuttering - saying um and like too much.

MD: Why do you think it’s important to have better fluency?

DEVON: (breathing) So people take me seriously.

MD: What have you been doing to work on fluency with Larry?

DEVON: I’ve been learning to take calming breath and breath pause. I’ve been learning to think of what I, think about what I’m going to say and pause more often when I’m speaking. I feel like I’ve really mastered this now.

MD: (laughs) Right at the moment it sounds great. When your fluency is improved, how does that change your life?

DEVON: It makes people care about me more, it makes people value what I have to say more.

MD: Has anything changed in your relationships?

DEVON: They’ve gotten better.

MD: How?

DEVON: Just, I’m able to connect to people better.

MD: When you had a voice with a more nasal sound. How do you think that made people feel? How did that come across to other people?

DEVON: It came across as being not very attractive. It came across as being almost annoying.

MD: I think sometimes it would just startle me. Sometimes you would start speaking in that nasal voice and I would jump. So how do you think you come across to people now with this more aural sound?

DEVON: I come across to people more normally.

MD: More normally, ok.

DEVON: How do you think my timbre sounding now?

MD: You sound beautiful now.

MH: You know it’s funny, I can hear him in that tape. Making those little huh sounds.

AA: It still doesn't come to him totally fluently. It’s still kind of hard.

DEVON: I just think that my life is kind of strange with relationship to other people’s lives, it seems.

MD: Really?

DEVON: My life is all about acquiring skills now. That’s what it seems - that my life is all about acquiring skills, whereas other people’s life seems to be about actually doing something.

MH: You know, he is much easier to listen to, and understand now. But what are the downsides here? He’s essentially hiding the fact that he has autism.

AA: Yeah. I know. I talked with Dr Dunn about this at length. She said that society demands a certain amount of adapting. If you are in the supermarket and you yell, people will move away. And if you can’t talk about anybody else’s topics, it’s hard to make friends.

MD: A lot of what we’re doing is helping them to pass. They try to go get jobs after they go get out of college and they can’t speak in a normalized kind of way. They speak in a very disfluent way or their voice sounds really unusual and people shut them down right away. They don’t even look at what their abilities are. Lots of times if you say, “I’m autistic, and that’s just it,” that doesn’t mean that people are going to accept you.

AA: Dr Dunn says for her patients with autism, typical social behaviors don’t come naturally. But with some work they can try on new behaviors. Put them on, check them out, see how they work. I wondered though, did she think that could be exhausting.

MD: I think that that’s the case sometimes - I think some of these guys also become so aware of the rules that they’re monitoring themselves a lot, and maybe monitoring themselves too much after a while, um, that that’s exhausting for them. But that’s part of what we deal with too - helping them to understand when their skills have reached a certain level where they can let go and relax and just be social and understand that there are all kinds of social mistakes that every one of us makes everyday and that they’re going to make them too and that’s okay. People will tolerate that.

AA: And to think - oh if only we had a world that accepted people who are different more easily-

MD: Wouldn’t that be nice? That would be so nice. (laughs)

AA: A few weeks ago, I asked Dr. Dunn to interview Devon again to see how he was doing. It’s been two years since he first started learning the technique and now you’ll hardly hear the “breath pause.”I sent a list of specific questions and I knew some of them would be hard, but Dr. Dunn faithfully asked each one.

MD: How old are you now?

DEVON: Twenty, that was an easy one.

MD: How is school going?

DEVON: I really like all my classes so far.

MD: Do you think that people can tell you are on the autistic spectrum?

DEVON: Yes.

MD: How do you think they tell that?

DEVON: Just, my voice sounds a little strange sometimes.My behavior is a little strange sometimes.

MD: Do you envy people are you jealous of people who don't have to work so hard at speaking well.

DEVON: Yes. Yes, I am a lot of times. It just seem like it comes naturally to most people. I often do feel envious of people who are not on the autism spectrum.

MH: It’s kind of heart breaking, to listen to. I feel like that’s what kind of comes through to me. That he knew exactly what he was missing, he just didn’t know how to get there.

AA: I think he just gets to choose now. Right?

MH: Yeah.

AA: He can present in a way where people don’t necessarily know. And he can choose who he tells and when he tells them. He’s able to communicate in a way that he can to the second and third and fourth conversation, as opposed to having everything shut down at the first.

DEVON: I did this club and I’m meeting people there.

MD: What club?

DEVON: Build on.

MD: What do you do there?

DEVON: I help people with… I help people with education and help, and help improve schools in like poor areas. By fundraising and and community service.

MD: That’s awesome.

DEVON: I’m also in a genetics club. And there’s going to be a Valentines themed...

MD: Wait, a Valentine’s Day themed what?

DEVON: Genetics of attraction.

MD: You’re kidding, the genetics of attraction for Valentine's Day.

DEVON: Yes.

MD: Sounds like a bunch of scientist at this Valentine's party.

DEVON: Because that's what it is. That's what it is. That's what it is.

MD: Okay, let me ask you a question. You’re making a lot of friends at this school. That's what’s happening?

DEVON: Yeah, that’s what’s happening.

MD: That’s pretty cool. How does that feel?

DEVON: Very nice. I like, think about a lot of other people like a lot now.

[Music]

AA: And what Dr. Dunn said is you can’t see is that he had a huge smile on his face when he said the last thing.

MH: I feel like I can hear the smile.

AA: I know...

[Larry’s Opera Singing]

MH: Dr. Michelle Dunn and Larry Harris have used this technique successfully with ten patients now. They are finishing up a teaching guide based on their work it’s called “The Music of Speech.”

If you or someone you know is on the autism spectrum,what do you think about this technique? Tell us your story.

Messick doesn’t want me to thank her this week, but I’m going to do it anyway. She helped us launch this show and this is one of the last episodes she had her hands on. We can’t thank her enough for her work here. Knock ‘em dead at Gimlet.