Why Reporter Nancy Solomon Chose True Crime

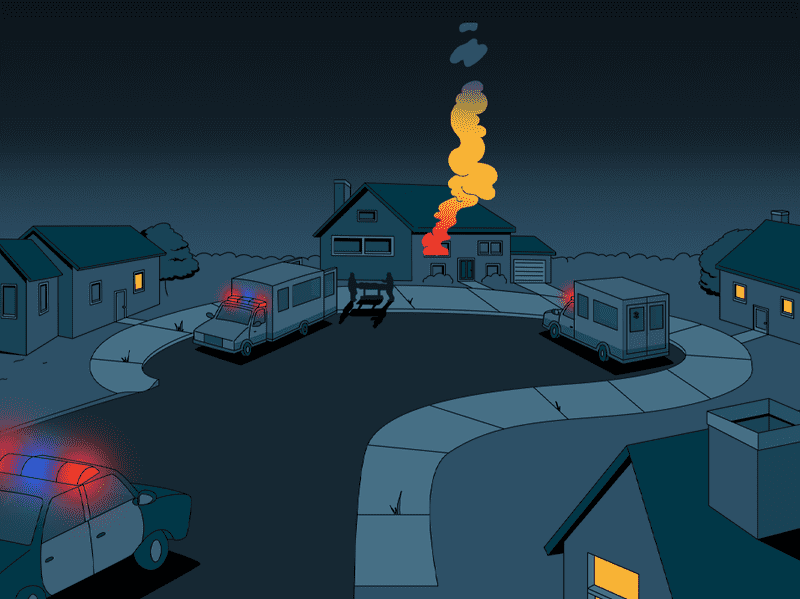

Brooke Gladstone: Earlier this year, the New Jersey Attorney General opened up an investigation into the killings of John and Joyce Sheridan, a well-known couple with personal ties to three governors. In 2014, they were found stabbed to death and their home set on fire.

Reporter: This morning, the mystery deepens over the death of John and Joyce Sheridan, a prominent New Jersey couple with powerful connections and close friends of Governor Chris Christie.

Bob: The first responders who came into the door of the Sheridan home early the morning of September 28th, found what could only be described as a house of horror.

Brooke Gladstone: Local police thought that John Sheridan murdered his wife and then killed himself. That was eight years ago. Why is the Attorney General revisiting the case now? Well, this year, our WNYC colleague, Nancy Solomon, released an investigation into their brutal deaths and found damning evidence of corruption at the highest levels in the Garden State. The series is called Dead End, a New Jersey Political Murder Mystery.

On the big show out on Friday, you'll hear an hour of that spellbinding coverage, but in this midweek podcast, I wanted to hear why, after 20 years of reporting on New Jersey politics, Nancy made the show at all. The idea first occurred to her in 2019. She was working on a project with ProPublica, and she found that a tax break program was being exploited by a powerful family in Camden, New Jersey.

During that reporting, she realized there was more to the Sheridan killings than the public had been told, but that thought didn't make it into that story. Instead, she focused on the political corruption.

Nancy Solomon: I'd spent a whole year working on that reporting, and it never really broke through. It never had what we call legs. It didn't feel like it went anywhere and that it got the kind of attention that I had hoped it would get. Those are hard stories to tell because they're very document-driven and as radio people, we love good tape, and I didn't have a lot of good tape. Those stories were just a bit dry and long and complicated, and so it just left me a little frustrated by the end of the year.

Brooke Gladstone: You said it was a year-long project, and you were looking into many party bosses, but you ended up focusing on the Norcross Brothers, right?

Nancy Solomon: Yes.

Brooke Gladstone: George Norcross was often described by the press as "one of the most powerful Democrats in New Jersey". Is that phrase straightforward or is that code for something?

Nancy Solomon: I don't think it's code necessarily. I think it's true, but it doesn't really tell you anything. I think, for many years, I wondered what exactly that meant. He's powerful. I get that, but how? What kind of power does he have? What levers of power is he able to pull on, and how did he get to be so powerful?

Brooke Gladstone: That started out as a story of outrageous conflict of interest and corruption in a tax break program in the poorest city in America. Somehow you found yourself staring down an old double murder case and that is what Dead End is about. In order to tell the old story and the murder story together, you landed on a new format, true crime, and that was a conscious decision because you love true crime.

Nancy Solomon: That's right. I guess my very first experience with detective stories was Nancy Drew, who I adored when I was a kid, especially since my name is Nancy.

Brooke Gladstone: That sort of thing matters a lot.

Nancy Solomon: I thought those books were written for me. In more recent years, I'm just a complete Scandinavian noir nerd and I like true crime podcast. All that was rumbling around in my mind in terms of what I actually consume as a reader and a watcher and a listener. I realized that if I could hook an audience with a compelling murder mystery, that then maybe they would stay along for the ride to understand the political corruption at work behind and connected in some ways to the murder mystery.

This spring, as we geared up and got ready to launch the podcast, I would lie awake in bed in the middle of the night, worrying that the audience was going to drop off as soon as we left the murder mystery and tried to explain the political machine and the real estate deal and the tax breaks. I thought, "Oh, people are not just going to not listen, but they're going to be mad at me." That's what I was afraid of.

Brooke Gladstone: You made those inextricably intertwined.

Nancy Solomon: To me, they are inextricably intertwined. That was one of the mind-blowing pieces of new information that no one had ever reported related to the Sheridan case.

Brooke Gladstone: You had all this, you had the somewhat arcane story of taxes intertwined with a, let's face it, addictive mystery about terrible murder. Did the strategy of yours to apply the true crime format to a story you'd visited before, did it work?

Nancy Solomon: Yes, absolutely. We're thrilled with the audience numbers that we're seeing.

Brooke Gladstone: How many listeners do you know that you've gotten?

Nancy Solomon: As far as I know, we're up over 3 million in two months. When I do a story that runs on the air, even if it runs on NPR on the national network, I'm excited if I hear from one or two people. Like, "Oh, I heard your story. It was so good, blah, blah, blah." This has just been unreal.

Brooke Gladstone: Here's the big question. This is a somewhat fraught genre. The gory details are what draw people in, but true crime can easily tilt closer to exploitation than justice. Also, the plot twists that keep people tuned in can feel manipulative and confusing, but, hey, that's the price of admission, as long as it doesn't mislead?

Nancy Solomon: I was really concerned about the Sheridan family and how they would feel about it and what it would be like for them. I was really super happy to hear from multiple members of that family about how pleased they were with the podcast after it came out. One of the other issues is, we thought long and hard about whether we would insert the usual narrative tool that many mysteries engage in, which is the red herring.

They present a solution to the crime that's starting to look like, "Oh, that must be it." You get really drawn in like, "That's the guy who did it, and it's looking like it's going that way. Oh, I'm so smart because I'm figuring this out ahead of what they're telling me." Then, of course, it turns out not to be true, and that person, whatever, has an alibi or didn't do it, and you move on to the next red herring.

I really did want it to unfold like a murder mystery, but I just couldn't. As a journalist, I couldn't put information into the podcast that I knew was not true. I just couldn't live with that. There were limits to how far we were willing to go.

Brooke Gladstone: When our producer asked you if there was anything about Dead End that you didn't want to give away in this conversation, you mentioned feeling a little conflicted about that.

Nancy Solomon: Yes. This is not the way that most journalists talk about their stories. It's a very weird thing to feel like you want the element of suspense and surprise for listeners to stick through to the very end. At the same time, I'm doing interviews and being asked about it, and it's weird for me to hold back information. I'm used to just laying out like, "Here's the story." Even doing it in what us reporters call an inverted pyramid, giving people the most important stuff first.

Brooke Gladstone: You noted in one episode of Dead End that you've covered a lot of bad guys in your career, but you never tried to actually solve a murder. You said that "The story is like a Russian Doll, every question I ask leads to another," but you actually did think you could crack this one, right?

Nancy Solomon: Yes. I guess. I do maybe watch a little too much TV, but I just thought if somebody really spent the time to look at everything and dig into it, maybe I would be able to crack it open.

Brooke Gladstone: Yet another amateur sleuth, so to speak?

Nancy Solomon: Yes, exactly. When you read those amateur sleuth stories or watch the series, you never see the brick walls that they come up against. The fact that they don't have subpoena power, that they can't get the investigative files from the detectives. These are things that don't come up when you're watching those shows, but I certainly came up against them and at a certain point realized that there was only so much I could do.

What ultimately happened was that I became increasingly frustrated with the fact that the Attorney General's office, which does have subpoena power, wasn't doing these things. I started to realize like, "Wait a minute, why am I trying to solve this murder? They should be trying to solve this murder."

Brooke Gladstone: You did uncover a web of corruption connected to the killings. You say, "My north star is not just about individuals, the good ones or the bad ones. It's the systems and the laws that got us here that we pay attention to." What did the Sheridans' deaths signify for you?

Nancy Solomon: A real collapse in the function of the state that is so critical which is to investigate and get to the bottom of suspicious behavior and activity that it appears to be riddled with, at the very least, conflicts of interest, if not fraud and extortion. I love being a reporter in New Jersey because it is so crazy and wild, and there is so much corruption, but you got to wonder at a certain point, like why? Why does New Jersey have more problems than other places?

To me, this was a big answer to that question, that we, the state of New Jersey, had a Division of Criminal Justice at the Attorney General's office, which had been set up to take on the biggest and most important cases, whether that was a murder of a prominent citizen that was quite suspicious, or whether that's a fraud case, or whether that's mob activity or extortion, whatever it is, the big, big problems in the state are supposed to be taken on by the Division of Criminal Justice, and it isn't doing that job.

That a prominent politically connected family in New Jersey couldn't get the Attorney General's office to intervene and investigate a case that was clearly mishandled by the local detectives. That was like a huge red flag, like, "What is going on here?" During the Republican administration of a governor, Chris Christie, a leading Republican is murdered and the Attorney General's office doesn't intervene. That to me is just a gaping hole and a big question that needed to be answered.

Brooke Gladstone: Even though you shrank from saying it, I will say that it certainly seems clear that your investigation did prompt the state Attorney General to take over the case and open an investigation. Now, given your experience with Dead End and the fact that your theory that the true crime format could get more people to care about political corruption really does work, has your approach to reporting changed at all?

Nancy Solomon: I was working with two masters of the craft, Karen Frillmann and Emily Botein, and I feel like I really did learn a lot about how to craft a stronger narrative. I've been a news person my entire career, and that sort of like short and sweet and get to the point and deals with the facts, generally. Whereas I think with something long-form like this, the place where I was coming up against my habits and my skills was that I would tend not to ask people how they felt about something. I'd ask, "What happened? What do you know? Where were you? When did this happen?" I didn't ever say, "And how did you feel about that?" Which makes me feel like I'm a therapist or something whenever I ask that question.

Brooke Gladstone: Maybe it just makes you feel like you're intruding.

Nancy Solomon: Yes. That too. That was one of the big lessons was to dig in a little more with people and push them to bear their souls a little more. There was a lot more of putting me into the story that I'm comfortable with. I think it really paid off. I think people really liked it.

Brooke Gladstone: You know one reason why they really liked it, Nancy, I think they really liked it because a listener, myself as a listener, could tell that you didn't love that part. That you did not want to make this about you. That you're fundamentally kind of shy, and I have to say that when there's somebody leading you through a radio piece, you don't want them to be this big character. There was nothing in your demeanor that suggested you wanted anything but to get to the truth of the situation. I think how you were made it so much more compelling.

Nancy Solomon: Well, thank you. That's nice to hear. Here I am in these waning years of my career and it was a huge lesson. I'm never comfortable calling attention to myself in that way, and I think I see now that it really helped tell the story. It really helped listeners attach to me as their narrator. It's interesting because, as you and I know, there is a real generational divide around putting yourself into the story and having a perspective and letting the audience know your perspective, and I'm quite steeped in the old school. This was a real leap for me into this newer kind of journalism, and so you can teach an old dog new tricks it turns out.

Brooke Gladstone: Nancy, thank you so much.

Nancy Solomon: Thanks, Brooke.

Brooke Gladstone: Nancy Solomon is a reporter at WNYC and host of the podcast Dead End, a New Jersey Political Murder Mystery. Coming up on Friday, you will hear a one-hour condensed version of Dead End, a multipart series. It is really worth hearing all of, but in the meantime, thanks for listening to this midweek podcast, and Nancy, thanks again.

Nancy Solomon: Oh, I'm super happy to be here. Thank you.

[music]

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.