Infinite Scroll

( Rick Bowmer / AP Photo )

DOCTOR WHO The library. Every book ever written. Whole continents of Jeffrey Archer and Bridget Jones. Monty Python's Big Red Book.

BROOKE GLADSTONE On this week's On The Media: Libraries. What they’re after and who's after them.

EMILY DRABINSKI It's not about the book. It is about wanting the library itself to disappear.

NITISH PAHWA It's about how we view books and how we view writing and how we treasure and arrange knowledge.

GYULA LAKATOS People can lose a lot of stuff. Humanity in general can lose a lot of knowledge out of nowhere for no reason.

BREWSTER KAHLE We can actually achieve the great vision of everything ever published, everything that was ever meant for distribution, available to anybody in the world.

EMILY DRABINSKI So I've never worked in a library that didn't have a bucket under a leak or a tarp over the archives.

BROOKE GLADSTONE The dream of accessing the knowledge of the whole world. And the risk of losing it all on the next On The Media from WNYC.

[END OF BILLBOARD]

BROOKE GLADSTONE From WNYC in New York. This is On The Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone. On the ballot in this week's midterm elections, where candidates and legislation that will define this nation's values, not just in Washington, but in every community. And this year, of course, we've seen some of the toughest battles fought in what once may have been seen as havens safe from it all.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT Libraries across the country say efforts to ban books have reached unprecedented levels.

NEWS REPORT A recent study found hundreds of books, mostly focused on LGBTQ themes or racial issues, have now been forbidden across the country.

NEWS REPORT Five years ago, this was anointed the best small library in America. Today, the trustees are facing a recall.

COMMUNITY-MINDED CITIZEN What I hate to see is my community torn apart like this.

[END CLIP]

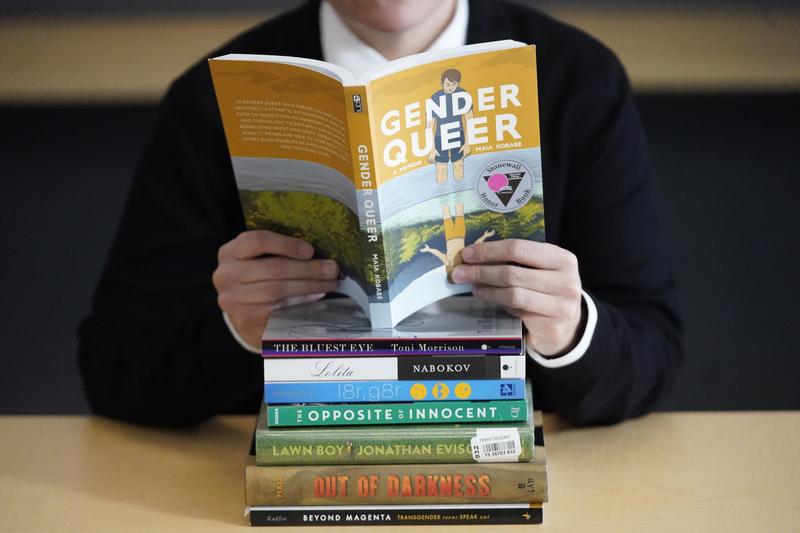

BROOKE GLADSTONE Citizens eager to join our fractious national fight find in their local libraries, their city councils, and school boards convenient fields of battle. As when last spring, when this school board meeting near Rockford, Illinois, proposed the removal of eight books from their school library shelves.

[CLIP]

PUNITIVE PARENT This does not belong in a school. If my neighbor down the road were to give this to my child, guess what? He would be in jail.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE In the end, only one book Gender Queer about a nonbinary child reckoning with their identity was banned. Other books at issue simply described what it was like being a black person growing up in America. Here's Ta-Nehisi Coates on his autobiographical book Between the World and Me being banned at schools in another Rockford, this one in Ohio.

[CLIP]

TA-NEHISI COATES When you start saying to a kid or your kids, ‘I only want you to read things that validate my point of view.’ That's no longer education. That's indoctrination.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE In the Tennessee State Assembly last April, Representative Jerry Sexton took on this question.

[CLIP]

JERRY SEXTON Let's say you take these books out of the library. What are you going to do with them? You can put them on the street, let them on fire.

JERRY SEXTON I don't have a clue, but I would burn them.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE The result of that debate was the state's Age Appropriate Materials Act of 2022, passed in August, which requires public oversight of all the books in Tennessee's school libraries. In Patmos, Michigan voters seem lukewarm on the mission of libraries altogether.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT Voters in Jamestown Township rejected renewing a millage that would support the community's public library.

NEWS REPORT They wanted the funding cut off because of LGBTQ books that were part of the Pride display.

NEWS REPORT The LGBTQ stuff bothers me with my kids in particular.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE The library director in Michigan resigned under the pressure of a pattern of book banning we've covered before but seems to be getting ever so worse. Prompting emotional responses like this from Jessie Graham, a Tennessee resident who spoke up at a recent board meeting for her public library, specifically calling out the Maury County commissioner, Aaron Miller, who's been critical of the library's books.

[CLIP]

JESSIE GRAHAM Our town has never seen so much homophobic crap as we have since Miller came along, and I’m sick of it! I've never been sexually assaulted at a drag show, but I have been in church – twice!

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE Emily Drabinski is a librarian at the City University of New York's Graduate Center and is incoming president of the American Library Association. She's looking how to navigate in the year ahead a time of unprecedented challenges for a service-oriented profession.

EMILY DRABINSKI Well, the field's about 88% white, mostly women. Most of us really want to help you. If there is something you need, we're going to do our best to get it. I think every time you email a librarian or call a librarian or ask a librarian a question in person, they'll either give you the answer or they'll say, ‘I don't know, but let me find out.’

BROOKE GLADSTONE It's a one year term, right?

EMILY DRABINSKI That's right. And I take office at the end of June.

BROOKE GLADSTONE You tweeted excitedly, “I'm a Marxist lesbian, and I won!” And for some reason, this elicited a bit of a backlash.

EMILY DRABINSKI It really did. And I was very surprised because the end of that tweet, which no one ever mentions, is that I also said, “my mom is so proud of me.”

BROOKE GLADSTONE It did show you had a loving mom. It doesn't really quite address the Marxist lesbian part.

EMILY DRABINSKI No. And it's very much who I am and shapes a lot of how I think about social change and making a difference in the world. But of course, I tweeted it into the middle of an extremely fractured society. One where we have the rise of an extremist right that has come for everything that I care about.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And accordingly, conservative media took on your tweet. The Breitbart piece had the catchy title, “Dewey Decimal Disaster.” I can't believe I'm saying this, but didn't Breitbart have a point when it said you brought an explicit political agenda? I mean, you wrote that the consequences of decades of unchecked climate change, class war, white supremacy, and imperialism have led us to the mess we're in.

You also noted if we want a world that includes public goods like the library, we must organize our collective power and wield it. The American Library Association offers us a set of tools that can harness our energies and build those capacities. You must have known that in espousing values other than the freedom of information, the err library value, that you are walking directly into a buzzsaw.

EMILY DRABINSKI Huh? You know, I didn't start the buzzsaw. The problem is not Breitbart publishing an article about me. The problem we're facing is disinvestment in public institutions and public goods. And I guess you could say I bring a political viewpoint to that, but I don't see how a person couldn't. All of us are working from a set of assumptions about the world and things that we see as normal. Those of us who are on the outside of the status quo, I would say we are forced to sort of articulate those ideologies to ourselves, but everyone is shaped by one.

BROOKE GLADSTONE The Federalist’s take on your appointment was headlined “Amid Public Concern about Grooming Kids, American Library Association Picks President Who Pushes Queering Libraries.”

EMILY DRABINSKI First, I would say that there are no public concerns about libraries grooming children. That is an extremist view of libraries. Almost no one in the public shares that view. I just would want to push back against any idea that this is a public concern. So these right wing attacks attempt to force us into talking about their agenda, and I'd like to talk a lot less about it to be honest.

BROOKE GLADSTONE You did speak to the Toledo Blade, and you said its coverage was a real surprise.

EMILY DRABINSKI If they had wanted to speak with me about how my understanding of the relationship between capital and labor shapes my understanding of political institutions and public institutions like the library, that would have been great. And to be honest, that's what I was expecting from the reporter. It hadn't occurred to me that people who really have an interest in telling the stories of people and communities and the libraries served them — it didn't occur to me that they would take the right wing talking points as the start of the story. The least interesting thing about the work that I'm going to be doing in the next couple of years and service to the community is the fact that I'm a Marxist lesbian. So when I tweeted that I was a Marxist lesbian, I certainly wasn't doing it for Breitbart. I was doing it for all of the people who agree with me that public institutions matter. Public resources need to attend to the things we need most, which is connection, public space, storytime, books to read. I mean, how many people do you know during the pandemic found out — in quotes — about electronic books from their library and suddenly were able to have whole worlds open to them during a time of crisis and isolation.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Less than a year ago on our show, we covered some of the ways that librarians have been caught in the crosshairs of the culture war, especially around pretty successful attempts to ban books, books by Black people, and also, of course, those dealing with the lives of LGBT+ people. One of those books, the book Gender Queer, I think that's where the “grooming” thing comes from. Now, you started your career at New York Public Library, the Jefferson Market Street branch. It's a predominantly gay area. You said that sometimes the context of the library suggests which books you need and which you don't.

EMILY DRABINSKI Well, librarians are professionals. We go through a library master's degree program, and we're trained on the job to make book selections for our communities. We build collections that are responsive to the needs of the people we serve. So right now, I'm talking to you from the Graduate Center in midtown Manhattan. My liaison responsibilities here to the School of Labor and Urban Studies and to our urban education program. I'm not going to choose Gender Queer to purchase for our library, not because I'm a censor, but because that's not a book that we need in our collection right now. But I think you can tell that it's not really about the books if you look to some of the particular cases. So, for example, attacks on the Boundary County Library in Northern Idaho. This was the same set of 300 books that they want banned. The extremist right in that part of the state came after the public library there. That library didn't own any of the books that were on the list.

BROOKE GLADSTONE They didn't have the books, but the library and the librarian were attacked nevertheless?

EMILY DRABINSKI Nevertheless. Because the books could be in the library, I guess.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Or the fact that it is a library?

EMILY DRABINSKI That's what I think. So when you look at what happened in Boundary County, they were unable to get insurance for the building.

BROOKE GLADSTONE I think that that librarian resigned.

EMILY DRABINSKI Yeah. You know, she had people parked outside of her house with guns, threatening her life, threatening the life of the people who worked in the library. And so it's not about the book. It is about wanting the library itself to disappear. We see that happening in Vinton Public Library in Iowa. The attacks were so severe that the people in the library refused to work there anymore and the library was effectively closed. Librarians out in Utah were telling me that a bill would require books added to school library collections be reviewed by a set of parents, boxes of books just sitting in school buildings, unable to get on the shelves because of these kinds of restrictive policies.

BROOKE GLADSTONE It's always framed as parents rights, but according to Summer Lopez, who's the chief program officer of free expression at PEN America, most of these book bans are on books that families and children can elect to read. They're not required to read them. They just exist.

EMILY DRABINSKI One of the things I loved about libraries when I first started is that they are non-coercive learning spaces. You don't have to read anything. You can choose from anything on the shelf. And if your kid checks out something you don't want them to read, that's between you and your child and the way that you're parenting. And it just isn't something that the state needs to be involved in.

BROOKE GLADSTONE You've said that part of your brief for your reign is to find and promote an affirmative narrative about what libraries do and what makes them vital to various communities. You've noted that rural libraries, for example, are sometimes the only anchor institution. Could you tell me what that means?

EMILY DRABINSKI Yeah. I just learned this idea of anchor institution at the Association of Rural and Small Libraries Conference. There are institutions that anchor communities. Right. So that the hospital is one. Lots of people work there. Everyone goes there at some point, has a role to play in the community and the library is similar. You'll often get people who will say that the library's are irrelevant, but that just means that they can afford not to use a public service. And I don't know why they are the people we ask to share their expertise on the use of public services. But most of us use the public library. Our kids get their picture books there. We maybe do passport services. Maybe the library has tech training. One of my first jobs at the public library was teaching senior citizens how to do mouse and keyboarding skills. So where else are you going to learn those things? You learn them at the library.

BROOKE GLADSTONE A librarian from Illinois told you that they have collaborations with the Diaper Bank and blood drives as well as schools. Libraries have also adapted to the fact that their communities may need them less for information, but may need them more desperately for other things like gardening equipment or getting a suit for a job interview.

EMILY DRABINSKI Yeah. All of those are services that libraries provide, the libraries fitting in and solving these problems. Because I do think one thing the librarians have in common is that were problem solvers. You definitely saw that in the pandemic. Libraries were one of the institutions that worked hardest and fastest to meet the needs of their communities.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Tell me about how?

EMILY DRABINSKI COVID testing. There's a program through the federal government and the Association of Rural and Small Libraries that would help public libraries set themselves up as COVID vaccine sites. Access to broadband Internet is a crucial public service that libraries do. During the pandemic, you saw all kinds of photos of people with their laptops leaning up against the door of the library. Maybe it was closed because of infection risk, but the broadband was turned on, you know, people taking their classes, sitting outside up against the wall of the Richland public library in South Carolina. I was talking to a librarian in South Carolina in the mountains where the only real way to get your own Internet signal, he said, was to go up to the top of a hill and hold your phone out. But where you did have that access was at the public library. Another librarian was telling me about his community's efforts to help people navigate the ERA, the Emergency Rental Assistance Program. You've got this program from the federal government, but if I don't have broadband Internet or access to Internet at all or a device, I can't apply for rental assistance. If I don't have an email address, I can't apply. If I don't know how to fill out an online form, which honestly can be pretty complicated, where do I go to get that assistance? That's a program where the librarians were working one on one with high-need residents to connect them to the emergency rental assistance program. Those services, increasingly, you can only access them on the Internet. So we're doing the essential work of bridging the person and the services. The role that libraries played in keeping people in their homes. It's not a thing that would come to mind immediately, but it is also a core function of the library.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Can you describe some of the challenges that libraries face that most people never even thought of?

EMILY DRABINSKI One of the things that the pandemic really brought home for me was how crucial the library as a space is. Somewhere to go to use the bathroom or get a drink of water or meet a friend. I have a 14 year old, and he is meeting his tutor today at 4:00 at the library so he can pass his math test. There's no other space where he could meet with her without having to pay money. And I was head of my library during the course of the pandemic and worked really hard to get us open as soon as it was safe so that people had somewhere to go. Students in New York City, they have crowded housing, very difficult time finding space where they can get quiet and do their work. My mother is out in Boise, Idaho, and she doesn't leave the house a whole lot anymore. But when she leaves, it's to go to the library and checks out seven books on a Wednesday, and then she goes back the next Wednesday and returns those checks out another seven books. So for her, it's a crucial link to the outside world. So the thing I guess I would say about what people don't know about that space is how much investment we need in infrastructure to maintain those spaces. So I've never worked in a library that didn't have a bucket under a leak or a tarp over the archives. There's a bill in Congress that would give $20 million of public funding towards maintaining the physical infrastructure of libraries.

BROOKE GLADSTONE That's a drop in the bucket.

EMILY DRABINSKI I tell you. We could eat that right here at the Graduate Center. The need is so high. We need resources to be able to make it the kind of public space that the public is worthy of.

BROOKE GLADSTONE When people lack a community, you've observed, libraries bring them back into the public square. There's events, there's storytimes. It's a noncommercial cross-class space — something we don't have elsewhere.

EMILY DRABINSKI But I'll tell you another story. So I was talking to a librarian at Donnelly County, Idaho, which is a city of, I don't know, 400 people, and they run an LGBTQ+ book club for teens. Gets about three people, and the librarian there was telling me that, for those three kids, that reading group at the library is the only place that they can be open and public and honest with themselves and each other about who they are. And I don't know who thinks that doesn't matter.

BROOKE GLADSTONE So what's your strategy for the next year? Will you be lobbying Congress?

EMILY DRABINSKI ALA has a Washington office that does advocacy work on behalf of the association. We're advocating for a federal Right to Read Act that would provide support for school libraries that make sure that every child and every zip code has a school librarian. Funding for broadband internet. Thinking about ways that we can provide digital corridors so that people can use the Internet wherever the library can manage to set up access points using bookmobiles and using hotspots. The commitment is to access to information for everyone. So while we're having to negotiate on the terrain that the right has set for us right now, that if we can tell more stories of what we are doing, that we'll have to pay a little less attention to these extremists. And then hopefully a library that is facing attacks for LGBTQ+ materials in Idaho, Michigan, Iowa, Wyoming, Florida, Texas, even New York, South Carolina, North Carolina — that all of those library workers know that they're not alone, that we have each other's backs, and that if we stand together, we're going to win. And I know that sounds like a bumper sticker, but I actually really believe it.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Emily, thank you very much.

EMILY DRABINSKI Thank you.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Emily Dubinsky is a critical pedagogy librarian at the Mina Rees Library at the Graduate Center City University of New York. Coming up, a lawsuit threatens e-book lending. This is On The Media.

[BREAK]

BROOKE GLADSTONE This is On The Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone. A few weeks back, attorneys filed a final round of briefs for a largely unknown case against the world's biggest free digital library: the Internet Archive.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT Several of the world's largest publishers have sued the Internet Archive for its emergency library of 1.3 million books, claiming the organization is engaging in willful digital piracy on an industrial scale.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE This case is potentially hugely consequential. Hachette v. Digital Archive could disable some digital libraries and cripple digital lending as we know it everywhere. Here's how and why: Back at the height of the pandemic, the Internet Archive lifted restrictions on its digital lending, basically making all books available to everyone all the time. This is not how it usually works. Usually the Internet Archive and libraries practice what's called “controlled digital lending.” This allows libraries to treat digitized materials just like print books. They purchase some and then lend them out to one patron at a time. Over and over, the four major publishers bringing the lawsuit were prompted by the pandemic era orgy of unbounded lending, now over and done with, to raise objections to what had become business as usual. The publishers claim that digital lending has bled them of millions and violates copyright laws. Some writers have chimed in as well.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT The problem came up when the Internet Archive said no wait lists. If we've managed to get our hands on a physical book, anybody can check it out as much as they want.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE Brewster Kahle, the founder of the Internet Archive, posted a video message to Facebook shortly after the lawsuit was filed.

[CLIP]

BREWSTER KAHLE This lawsuit is not just an attack on the Internet Archive. It's an attack on all libraries. The publishers want to criminalize libraries owning, lending, and preserving books in digital form.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE As of early November, the site holds a treasure trove of over 35 million books, 8 million videos, and also some 734 billion Web pages offering a kind of history of the net in its Web archive called the Wayback Machine.

NITISH PAHWA Anyone can log on to there and look up any websites and see what they look like a number of years ago.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Nitish Pahwa is a web editor and writer at Slate. He says the Wayback Machine is a chronicle of Internet history going back to 1996, which would be equivalent pretty much to a little after the founding of America in 1776.

NITISH PAHWA 1996 is such a huge year for media in general. I mean, you have the Declaration of the Rights of Cyberspace. You have the vision being laid out for a very open web. You also have the Telecommunications Act, which will, of course, end up doing a number on radio stations across the country. You have this influx of differing visions of what 21st century media is supposed to look like. And we've basically found out that it's going to be how capitalism works in America — a lot of tech giants, people with financial stakes in these things.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Which brings us to the case in question. During the pandemic in 2020, it launched a national emergency library and made 1.4 million books available for free, any number of them for as long as you want. Some of these books — it didn't have the rights to. To be clear, in controlled digital lending, a library scans each page of a physical book that it already owns, uploads a digital copy, generally allows one person to check it out for a period of time. So what you've got in the National Emergency Library is no limits on copies and no limits on time. And it was the limitlessness of this library that the publishers and writers objected to.

NITISH PAHWA Exactly. A lot of publishers have really not cared for the Internet Archive or its open library system for a while. There have been squabbles over this going back to when Google Books started up scanning pages, although in that case, when authors were suing Google, the law came in on the side of Google because only portions of books were available, whereas in the Internet Archive, in both the Open Library and the National Emergency Library, everything was just available.

BROOKE GLADSTONE It seems like they aren't happy with controlled digital lending either, which is pretty much the electronic version of what the library does with its paper and cloth books, which is lend them out for a period of time. They don't pay the publishers every time someone reads the hard copy of their book. So they're calling into question the basic practice of book lending that has been used for centuries. Am I missing something here?

NITISH PAHWA Yeah, that's definitely a way of looking at it. I do think that the battle here is more over digital versions of books than physical books themselves.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Right. But theoretically —

NITISH PAHWA Theoretically, absolutely. If this system were applied to physical books that are checked out and handed to you, that would mean a lot more money from libraries to publishers and would very likely affect how many physical books are available in your local library.

BROOKE GLADSTONE The publisher's argument is pretty straightforward. The archive shares their intellectual property, and now they have to pay them back. I think I get that argument. I just don't understand how they have the gall of making it. I mean, when Benjamin Franklin and company decided to create the library system, it was done with the assumption that the library would only have to pay once for the book. So how does the archive defend itself against this, since they ended the emergency limitless practice that they were using at the beginning of the pandemic and they're back to their old way of doing things?

NITISH PAHWA The archive is defending itself by saying, ‘Look, the emergency library was an emergency. The typical ways of access to books and literature is completely shut off.’ So they're trying to argue that that creates a fair use case. Some authors want their work out there, even if it means sacrificing some sales because access and availability is far more important than monetary gain. And they're arguing that this doesn't actually cost publishers all that much money.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Stay with the author's position. It isn't uniform, as we know. But the original authors spoke out against the National Emergency Library, including Chuck Wendig, N.K. Jemisin and Colson Whitehead. Have they changed their views?

NEWS REPORT There are a lot of authors who came out very strongly, like those you just named, against the archive and the emergency library. And then they deleted those messages later on and they just don't answer any more questions about their stance. Chuck Wendig says, “Now I would like to be excluded from this narrative” basically.

BROOKE GLADSTONE A little late for that, but okay. Yeah.

NITISH PAHWA And others like Neil Gaiman say that they were misunderstood from the outset, that they support the archive and libraries in general. You know, there's a lot of coverage around this that makes it look like if this goes through, there will be a hit to the Internet Archive financially. And maybe that means that there are other services are crippled. Most people can agree that the Wayback Machine is a very important resource. No one wants to lose that, least of all authors who can use it for research. How many online publications have closed over the past decades? And the archive snapshots are the only records of those.

BROOKE GLADSTONE In terms of the threat to the Wayback Machine, the Internet Archive says, ‘if you're charging us this much to lend books, it's going to threaten the whole operation.’ Do you think that's a credible claim?

NITISH PAHWA Of course. When it comes to copyright claims changing the way of lending, no matter what, the archive takes a financial hit. It's a nonprofit. The data centers the power that they need to keep everything they have up there and alive depends a lot on donors and requires tens of millions of dollars every year. It is not a cheap venture.

BROOKE GLADSTONE If the Internet Archive loses the suit, does that mean all libraries that lend out digital books according to the control lending process — would they have to change that practice as well?

NITISH PAHWA Absolutely. You know, however many libraries are employing controlled digital lending right now. They would have to stop that and figure out their own monetary damages and their scale. And this would apply to movies, audio recordings, sheet music. Libraries will have to rethink all those, too. Maybe the Internet Archive just stops having open library altogether, but they keep operating everything else. And libraries that look to control digital lending as a way to save some of their costs are not going to have that option.

BROOKE GLADSTONE They would have to pull back on lending the physical copies, which means that readers or scholars, historians, would have to be physically present like they were, you know, back in the early nineties and all the years prior to that.

NITISH PAHWA Yeah, exactly. And I know that that is a concern for some authors who view this as, ‘Look, we want people with disabilities, people who can't go to physical storefronts, to be able to access our work still.’

BROOKE GLADSTONE It makes me wonder, do publishers really want to be in the position of threatening libraries and library systems in this way? I mean, is it clear to everybody what this lawsuit could mean?

NITISH PAHWA I don't think it is, frankly, to readers, to authors. Copyright law is its own whole world, especially in the digital age. They're constant battles to be had over it. I was reading this morning actually that there is this library hoping to lend out unlimited copies of Toni Morrison novels like The Bluest Eye and Beloved in the face of book bans that have been taking over the entire country, which is a very, I think, noble thing to do. The ability to do even something like that, whether on a temporary or longer term basis, would also be impeded.

BROOKE GLADSTONE So you have likened the potential loss of the Internet Archive to the burning down of the Library of Alexandria. But it's really not just about the Internet Archive at all.

NITISH PAHWA It's about copyright. It's about libraries. It's about how we view books and how we view writing and how we treasure and arrange knowledge, basically. I talked to the author and journalist Stephen Witt for the piece, and he put it in a very nice way, I think, which is that, you know, ultimately this suit is also a big closing of the door on the very concept of a much more free and open Internet. No matter which way this case swings, it's going to change a lot. You know, should the archive prevail? You know, CDO-controlled digital lending could become even more popular. And we could see a lot more of that sharing of knowledge libraries are there to do. If not, then we're not going to get that and we're going to have definitely more barriers to access.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Nitish, thank you very much.

NITISH PAHWA Thank you for having me.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Nitish Pahwa is a web editor and writer at Slate. Coming up. For centuries, innovators and storytellers have been inspired by a legendary library. This is On The Media.

[BREAK]

BROOKE GLADSTONE This is On The Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. Last week, a popular website called Z Library, that gave readers access to e-books online for free, was taken down. One reader denied took to Tik Tok.

[CLIP]

TIKTOK The United States authorities taking down Z Library is essentially the modern day burning of the Library of Alexandria.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE The burning of the Library of Alexandria is invoked whenever our access to books is lost or threatened. But for centuries, it's also inspired scientists and inventors, philosophers and programmers to envision or even build a better library. A perfect library. One that stocks every book ever written, the kind of library that may have actually existed once. On The Media producer, Molly Schwartz went to her local library to meet some of the people trying to build a universal repository of human knowledge, to learn what kind of progress they've made and what keeps the dream alive.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ It's a gorgeous fall Saturday in Brooklyn. Mild chill in the air. Colorful leaves. General good vibes. And I'm on my way to a birthday party at the Brooklyn Public Library at 9:30 in the morning.

[CLIP]

BROOKLYN PUBLIC LIBRARY Welcome, everyone, to Wiki Data Day. Today is Wiki Data Day, it's the 10th anniversary of wiki data. So Wiki data is sort of the data science side of Wikipedia.

[END CLIP]

MOLLY SCHWARTZ You know, Wikipedia, the free online encyclopedia with millions of articles and hundreds of languages all written by volunteers. Jim Henderson is one of them. And today he's wearing two hats. Literally.

JIM HENDERSON This is the data hat, something I ordered when I was on the board of directors of the local club.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ The data hat says I heart Q60. Q60 is wiki data for New York City. On top of it, he's wearing a beanie that says Wikimania Capetown.

JIM HENDERSON When we had our next to last Wiki-mania worldwide convention.

JAMES FORESTER So we have this kind of mission statement for the Wikimedia movement.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ James Forester is a software engineer at the Wikimedia Foundation.

JAMES FORESTER Imagine a world in which all people have access to the sum of human knowledge.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Providing everyone on the planet access to the sum of human knowledge. That's the prime objective of Wikipedia, as stated by co-founder Jimmy Wales.

JAMES FORESTER I mean, it's a mission statement, right? You're not meant to achieve them. You're meant to move towards them. And definitely we've moved a huge amount towards them in the last 20 years — pushed the ball along the road a little bit.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ As the day goes on, I learned about Wiki Data properties and qualifiers. I also get in a little bit of trouble because On The Media's Wikipedia page isn't up to date.

[CLIP]

WIKI DATA DAY Add in Suzanne Gaber. Publish the changes, and it's done. You need some more links.

[END CLIP]

MOLLY SCHWARTZ And I spoke with someone who's thought a lot about universal libraries and how they work.

RICHARD KNIPEL I grew up with the 1940s Britannica and 1960s World Book, and I wanted to contribute to the sum of knowledge.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Richard Knipel is the president of Wikimedia in New York City. But in the world of Wikipedia, he's known by his username Pharos.

RICHARD KNIPEL Named after the Pharaohs of Alexandria, the lighthouse of Alexandria. It's in homage sort of to the Library of Alexandria.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Perhaps the closest thing there ever was to a universal library, a bastion of all the world's knowledge for all who seek it.

RICHARD KNIPEL We actually had our international Wikipedia conference. We had Wikimania was in Alexandria a few years ago. And people do feel a strong cultural resonance with the Library of Alexandria and other universalizing attempts at knowledge.

ALEX WRIGHT For some reason, the Library of Alexandria has captured people's imagination, and it was certainly the largest library of its era.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Alex Wright is the author of the book Glut: Mastering Information Through the Ages. He says the Library of Alexandria was built in Egypt in the third century BCE, likely by decree of the pharaoh Ptolemy the First.

ALEX WRIGHT And he tried to attract as many notable scholars as he could to come and contribute to the collective enterprise of building not just a library, but a university and a center of learning.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Ptolemy's mandate for the Library of Alexandria was as ambitious as it was simple: collect everything. Every papyrus, scroll, every book, every manuscript. By force, if necessary.

ALEX WRIGHT When ships would come to Alexandria, officials would basically seize the books on the ship and add them to the library.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ They lifted books from private citizens, stole them from docked boats, and allegedly took books by a subterfuge from Athens. But despite the Ptolemy's best efforts, Alexandria could never really compete with Athens. Athens was this organic center of culture and learning, whereas in Alexandria, all the scholars were entirely beholden to their employer, the Pharaoh. So as the Ptolemaic empire crumbled, so did the library.

ALEX WRIGHT There's this deeply intertwined relationship between libraries and state or governmental power, and you find that the great libraries of the world have not coincidentally emerged alongside powerful empires or civilization.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ What happened to the library is actually unclear. Some say Julius Caesar burned it down. Others say a conquering Muslim commander burned the books. And others say that the library never succumbed to a fire at all, but rather to years of neglect and changing empires.

ALEX WRIGHT We don't know for sure exactly what happened. We do know for sure that the library no longer exists and that the 500,000 odd volumes of material there have, for the most part, been lost to posterity. And yet there's something apparently kind of energizing about that ideal that has inspired a lot of people over the years to try to work towards some kind of universal repository of recorded information.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Versions of Universal Libraries, Pepper Science and Speculative Fiction. From Jorge Luis Borges’s Magical Library of Babel.

[CLIP]

MAGICAL LIBRARY OF BABEL The universe, which others call the library, is composed of an indefinite, perhaps infinite number of hexagonal galleries.

[END CLIP]

MOLLY SCHWARTZ To Isaac Asimov's Imperial Library and the Foundation series.

[CLIP]

LIBRARY AND FOUNDATION An Imperial Library on Chancellor Stacks, I'm assuming, was Wooden. There are all these marble busts.

[END CLIP]

MOLLY SCHWARTZ To Douglas Adam's Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy.

[CLIP]

HITCHHIKERS GUIDE TO THE GALAXY The Hitchhiker's Guide has already supplanted the great Encyclopedia Galactica as the standard repository of all knowledge and wisdom.

[END CLIP]

MOLLY SCHWARTZ To the TV show Doctor Who.

[CLIP]

DOCTOR WHO The library. Every book ever written. Whole continents of Jeffrey Archer and Bridget Jones. Monty Python's Big Red Book.

[END CLIP]

MOLLY SCHWARTZ There's even a universal library in the world of the occult. According to Theosophists.

[CLIP]

THEOSOPHIST The Akashic Records is a place within a different dimension. It's a higher dimensional energy that is like the library of the universe. It holds all the records of the universe. And anybody can tap into this energy, into this knowledge, and access it for themselves.

[END CLIP]

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Around the invention of Gutenberg's printing press. The Vatican Library was also founded. According to Pope Nicholas the Fifth. The goal was ensuring, quote, “for the common convenience of the learned. We may have a library of all books in both Latin and Greek that is worthy of the dignity of the pope and the apostolic sea.” And then in the late 19th century.

ALEX WRIGHT Suddenly printing of books became a industrialized mechanized affair.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Alex Wright.

ALEX WRIGHT And you start to see this explosion of popular literature, magazines, what they sometimes called penny dreadfuls, these cheap little precursors to tabloids.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ It was during this explosion of books that people started paying attention to how to organize and retrieve them using universal classification systems.

ALEX WRIGHT That was when Melvil Dewey invented his decimal classification. There was another guy named Charles Cutter, worked in the Boston Atheneum who developed a different classification system that's now used in a lot of academic libraries in India. There was a librarian named Ranganathan who developed a really highly sophisticated method that he called “faceted classification.”

MOLLY SCHWARTZ And then in the 1930s, with huge leaps in technological progress following World War I came another burst. This is when the visionary H.G. Wells published a series of short stories. In them, he explained a concept called “The World Brain.”

[CLIP]

ARCHIVAL CLIP There is no practical obstacle, whatever now to the creation of an efficient index to all human knowledge, ideas and achievements through the creation that is of a complete planetary memory for all mankind.

[END CLIP]

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Around the same time. Paul Uplay, a librarian in Belgium, envisioned the world book.

[CLIP]

ARCHIVAL CLIP Here, the workspace is no longer cluttered with any books in that place. A screen and a telephone within reach over that an immense edifice are all the books and information. Cinema, phonographs, radio, television. These instruments will in fact become the new.

[END CLIP]

MOLLY SCHWARTZ And Vannevar Bush, who worked for President Truman as what was effectively the nation's first science adviser, wrote about a memory supplement that he called the Memex.

[CLIP]

VANNEVAR BUSH The analytical machine, which will supplement a man's thinking that which will think for it will have as great an effect as the invention of the machine. Way back to the load off of men by giving them mechanical power instead of the power of their muscles.

[END CLIP]

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Basically, these imagined groundbreaking gizmos are proto computers and proto search engines. They were all invented and more and better. And with all of this came another round of optimism starting in the 90s and picking up speed in the aughts and 2010s that the dream of a universal library could be realized via the Internet.

BREWSTER KAHLE I'm a librarian, and the idea of using technology is perfect for us.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ That's Brewster Kahle, again, the founder of the Internet Archive, who we heard from earlier in the show.

BREWSTER KAHLE I think we can one up the Greeks and achieve something. Yeah, we could actually achieve the great vision of everything ever published, everything that was ever meant for distribution available to anybody in the world that's ever wanted to have access to it.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ There was a host of these projects all at the same time because people all had the same vision. Put books online. There was also the Universal Library Project, which was later largely supplanted by HathiTrust, which is this massive cache of digital content that's available to a group of research libraries. And then there are projects ranging from the World Digital Library to the Digital Public Library of America and all kinds of smaller offshoots.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT Walk into the Bear County Digital Library in San Antonio, Texas, and you'll see plenty of screens but zero books. This doesn't look like a library.

NEWS REPORT No.

NEWS REPORT That's the point.

NEWS REPORT That's the point.

[END CLIP]

MOLLY SCHWARTZ But the one that probably had the grandest vision, the most top down, the most completist, was the Google Books project. Google transported truckloads of books to their massive scanning centers across America, and they got their technology good enough that they were scanning about a thousand pages an hour. Since 2004, they've digitized over 20 million books, and they had plans to literally digitize every book in the world. Google Books was a huge deal. The company's first moonshot, the first salvo in a revolution.

[CLIP]

ARCHIVAL CLIP What is being discussed tonight is not your ordinary kind of revolution. Like cars and jets. It is a super revolution, like writing and printing and computers.

[END CLIP]

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Google Books were sued by the Authors Guild for violating copyright. Ultimately, Google won, but only because they only show snippets of most books. A far cry from the initial vision of universal access.

GYULA LAKATOS Unfortunately, I'm still using a mobile Internet plan.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Gyula Lakatos is a software engineering consultant. He lives in a house. On a hill in a small town in Hungary, on the banks of the Danube, too far from Budapest to get high speed Internet. And that's a problem, because he's working on a very large project housed in two servers stacked behind him.

GYULA LAKATOS One of them is running 20 hard drives. The other one is 10.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Lakatos is using those servers to save just a little bit of today's digital flood for posterity. Inspired by deep admiration for the ancient empires of Greece and Rome, and fearful that modern civilization will suffer the same fate as those lost knowledge centers.

GYULA LAKATOS As far as I know, only around 1% of books and documents survived from classical antiquity.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ Which made him wonder what's going to be left from life today?

GYULA LAKATOS So I created an application suite. It's not just 1 to 7 applications. You can deploy these applications to crawl the web.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ He spent about $6,000 on equipment that ran his applications for two years, amassing over 90 million documents onto the servers in his house. His application suite is open source and available on GitHub, and you'll never guess what it's called.

GYULA LAKATOS It's called Library of Alexandria.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ At this point, he's collecting around 2 million documents a week. They include everything from interesting, complex doctoral dissertations to the kind of ephemera of restaurant menus to a weird collection of Russian passports. It's a mishmash of the valuable and long forgotten all hoovered up and stored in the hills of Hungary. Lakatos wants to open up his treasure trove to the public. But for now, it all just lives on his servers because he's afraid about copyright laws and navigating copyright laws for 90 million documents. That's a job for more than just one person.

GYULA LAKATOS I don't really want to host it, to be honest. I'm a lazy person. I just want to search in that library. That would be a lot of fun.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ I came across the Lakatos project on a subreddit called Data Hoarder. It's a forum for people with a kind of unusual hobby, trying to preserve things they find on the Internet. They hoard this data in their living rooms and corners of the web, and sometimes on places where a lot of the web is hosted — Amazon Web Services or AWS. It's all to try to preserve a first draft of history for the future.

GYULA LAKATOS Humanity in general can lose a lot of knowledge out of nowhere for no reason. Imagine that, for example, a fire is starting in one of the AWS warehouses, that a lot of things are hosted and people just lose their data. Like the whole Data Hoarder subreddit is very concerned about this and I just wanted to kind of notify people with this name a little bit or warn them a little bit more.

MOLLY SCHWARTZ I appreciate these data hoarders. I got my degree in library science because when I stood in the rare books room at my university, I felt a sense of awe, like I'm part of a story that began long before I was born and will go on long after I'm gone. I hope. In the glut of information, more gets lost than saved. And that's not always a bad thing. One of the first things an archivist learns is that the best way to save things is to know what to throw away. Have you ever noticed that the material on which knowledge is stored has gotten more ephemeral over time, from carved stone to parchment to paper to tape and floppy disks to drives for outdated devices, to everything stored in a cloud. Prey to all kinds of terrestrial and cosmic events. The fact is, preserving all the world's knowledge is like building a dam against the unyielding torrents of time. It's impossible. But if we don't keep trying, how will anyone know we were ever here?

MOLLY SCHWARTZ For On The Media, I'm Molly Schwartz.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And that's the show! On The Media is produced by Michael Loewinger, Eloise Blondiau, Molly Schwartz, Rebecca Clarke-Callender, Candice Wang and Suzanne Gaber with help from Temi George. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson, our engineers this week were Andrew Nerviano and Mike Cushman. Katya Rogers is our executive producer. On The Media is a production of WNYC Studios.

Before I let you go, I wanted to let you know that we will be airing a brand new reported series starting next week. Kat has been hard at work editing it with reporter Katie Thornton. It's the story of how decades of regulatory erosion and pressure from the right enabled a near takeover of talk radio and how one company in particular is stealthily radicalizing communities right now. To listen, subscribe to On The Media, wherever you get your podcasts.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.