The Reporter Who Said No to the FBI

Brooke Gladstone: This is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone. Shortly after the subpoena landed in Micah's email inbox, he began looking for examples of other reporters who'd navigated similar experiences, which is how he stumbled upon the story of one remarkable journalist.

Male Speaker: We're interviewing Earl Caldwell this afternoon. I'll be inspiring Earl to speak on various issues connected with his career.

Micah Loewinger: This a 2001 oral history done by the Maynard Institute for Journalism Education. Thank you very much to the institute for giving me permission to use it extensively in this piece. Earl and I spoke many, many times over the phone, but he never agreed to speak with me on the record. He's writing a book about his life and he stop doing press.

Male Speaker: How long was that?

Earl: It's two hours plus a few minutes. Once I start to run my mouth, it's all easy.

Micah Loewinger: The story begins when Earl Caldwell, then a reporter in his early 30s, joined the New York Times.

Earl: There was only one other Black reporter on the staff when I got there, and what was approaching was the summer of '67 which was to be like no other summer in the history of the public.

Male Speaker: A worse race riots since those two years ago in the Watts section of Los Angeles, rock New Jersey's largest city Newark for five consecutive days and nights.

Earl: Law and order have broken down in Detroit, Michigan. Pillage, looting, murder, and arson have nothing to do with Civil Rights.

Micah Loewinger: The paper flew Earl all around the country to cover the riots and the Civil Rights Movement, and in April 1968, the Times sent him down to Memphis, Tennessee to interview Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Earl checked in at the Lorraine Motel where Dr. King was also staying.

Earl: Dr. King gave me an interview. While we're standing on that balcony talking, he begins to ask me about my personal life, how I got into the newspaper, how long have I been a reporter at the New York Times.

He's said, "We'll talk again tomorrow because we don't have a chance to go through everything. Nobody told me there was a going to be a big rally that night, which turned out to be a very historical moment and that's where King made his mountain top speech.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr: We've got some difficult days ahead, but it really doesn't matter with me now because I've been to the mountaintop. [crowd cheers]

Micah Loewinger: Earl only learned about this speech later because he was back at the motel.

Earl: It was this fierce storm like it was lightning and thunder [unintelligible 00:19:46] were rattling and everything.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr: I've seen the promised land. I may not get there with you, but I want you to know the night that we as people will get to the promised land.

Micah Loewinger: The next morning. Earl heard about the morbid premonitions in King's speech, and the way Earl describes this day sounds like a bad dream. That dread when you're rushing somewhere, but you feel like you're treading water.

Earl: I'm trying to get to King right away and I can't get to him, and the day is getting away from us, and I was missing my deadline.

Micah Loewinger: I imagine him pacing around his motel room, chain-smoking cigarettes, trying to figure out what to do when he heard a loud noise outside.

Earl: I heard what I thought was a bomb blast man. I run out there, my shorts. What happened? Then I ran up to the balcony and I saw Dr. King could see those horrible wounds, huge, bigger than your fist in his jaw and neck.

Male Speaker: Dr. King was standing on the balcony of a second-floor hotel room tonight when according to a companion, a shot was fired from across the street in the friend's words, "The bullet exploded in his face."

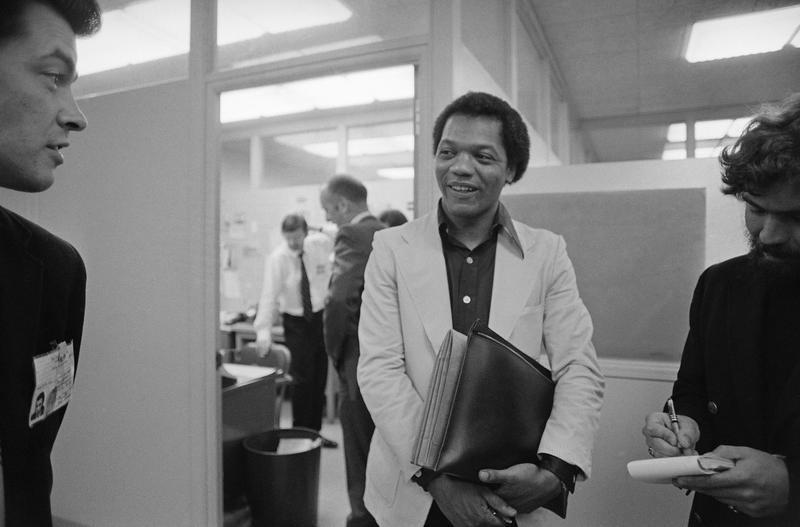

Micah Loewinger: You can see Earl in some of the earliest photos of the assassination in the scrum, hovering over MLK on the balcony. He was the only reporter on the scene and the first to break the story.

Earl: That was indeed the biggest story I ever had.

Micah Loewinger: It was actually the next big reporting project that's the focus of my story.

Earl: The New York Times sent me out to California to look into this group that had been rising in California and was coming to some national prominence called the Black Panther Party.

Micah Loewinger: Within a matter of months, Earl had developed deep access within the group.

Lee Levine: It wasn't easy, even for a Black reporter like Earl to gain the trust of the Panthers.

Micah Loewinger: Lee Levine is a media law expert. He's writing a book about Earl Caldwell.

Lee Levine: The way he did it was providing what the Panthers considered to be fair coverage. He was not a misrepresenting who they were and what they were doing.

Earl: I got so on the inside that I saw the Panthers moving a large cash of weapons from San Francisco to Oakland, where Huey Newton, the leader in the Panthers, was on trial for murder of a police officer.

[music]

Male Speaker: 3000 Black Panthers turned out for the start of the trial. Spokesman say that if Newton is found guilty and given the death penalty, the sentence will have to be carried out over their dead bodies.

Earl: I put the story in the paper, and when that story came out, the FBI came to the New York Times and demanded that I give them additional information about these weapons and how I knew it, where they were all this stuff. I said, "What I know about this, I put it in the paper and everything." "Well, look, you're there all the time. We want an inside report. We want you to tell us everything that you're getting, everything you know it." Ooh, I said, "Not only could I not do it, I can't even have this conversation with you." They began to call every day.

Lee Levine: We now know that in fact, the FBI had informants among reporters who they could plan stories with. There are multiple examples of what is called COINTELPRO, which is its counterintelligence program directed at a variety of what the FBI deemed to be subversive groups, which included the Panthers.

Micah Loewinger: 40 years later, Earl was shocked to learn that his friend Ernest Withers, a prominent civil rights photojournalist, had been an informant much of his career.

Earl: Finally one day they called Mrs. Brackett. They said, "You tell Earl Caldwell we're not playing games with him," and they got a subpoena for me to be the star witness against the Black Panthers before a federal grand jury.

Lee Levine: He had two strains running through his head. One was, as a journalist, I'm not going to be a snitch for the FBI. Then not inconsistent with that, as a Black person, I am not going to let the FBI use me to advance their goals against other Black people.

Micah Loewinger: To make matters worse, the government also wanted his reporting materials, including the unpublished stuff.

Lee Levine: Earl had a boatload of documents and tapes, a lot of recorded interviews with the Panthers, and they were all in a storage room at the Times Bureau.

Micah Loewinger: Earl discussed his archive with a lawyer at a fancy San Francisco law firm that the Times had hired to deal with the subpoena.

Earl: The guy says to me, "Look, we have a tremendous problem with law and order out here."

Lee Levine: Went on, according to Earl, to talk about the problem with Black militant violence, [laughs] Where the guy told him to bring in his notes and stuff so that he could go through them and told Earl that "I think there's probably stuff that you have that the government's entitled to." [laughs] That totally freaked Earl out.

Earl: I'm sitting there thinking like, "You're in an awful situation because you're at the top of your career and all of a sudden they're saying something that could get you killed." It wasn't. Then somebody would say, "Go shoot Caldwell." It was in this environment, somebody would say, "If he came out here and told us he is a reporter and got all this access and he's a spy for the FBI now, he shouldn't live."

Micah Loewinger: Earl learned that the feds were going to come to the San Francisco Bureau to serve the subpoena.

Earl: We didn't know what to do and had all these documents. We just said, "We'll destroy it." Let's just shred everything. Let's dig these tapes apart, cut them out, and everything. We had two of these real high garbage cans. We filled them up.

Micah Loewinger: Ultimately he decided to fight the subpoena in court. Because of his frustrations with the paper's legal team, Earl hired Anthony Amsterdam, a white lawyer recommended by the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. Amsterdam was confident that Earl could beat the subpoena, Lee Levine.

Lee Levine: My feeling is that in reality, the reason the subpoena was issued was because Earl among a few other reporters, was giving a view of the Panthers that was contrary to the government, and specifically the FBI's preferred narrative to drive a wedge between Earl and the Panthers. They didn't need documents, they just needed to call him before a grand jury and have him testify behind closed doors, which is what happens in a grand jury.

Micah Loewinger: The Panthers wouldn't know what he said or if he said anything.

Lee Levine: Correct. Even if all he did in the grand jury room was assert his privilege not to answer substantive questions. I think the Panthers justifiably given what the FBI was up to, would have been nervous and would have cut off access to him.

Micah Loewinger: Actually this became a big part of Anthony Amsterdam's defense for Earl. They rooted this idea of reporters' privilege in the First Amendment.

Lee Levine: Everybody understands that the First Amendment prohibits the government from preventing publication in advance. That's called the prior restraint. That's the Pentagon Papers. Everybody also understands that the government can't penalize you after the fact for publishing information that relates to a matter of public concern, especially if it's true. What Earl was arguing is something different, but I think equally important, which is that even actions that government takes that don't directly prohibit or penalize the dissemination of information can have the effect in operation of depriving the public of important information about matters of public concern, and that that has an impact on the free flow of information that is analogous to a law that penalizes a reporter for publishing information after the fact.

Micah Loewinger: This is essentially what I was concerned about when I got my subpoena. If people come to suspect that all reporters are just secretly working on behalf of the government, this social contract propping up journalism pretty much just falls apart.

Lee Levine: Do you want me to go on and talk about what happened next?

Micah Loewinger: What happened next was that the court was sympathetic to the argument, but still ruled that Earl should go before a grand jury to authenticate his reporting. The Times thought this was a fair ruling, and Earl was happy to say that what he'd written was true, just not behind closed doors.

Lee Levine: Earl decided to appeal and the Times, I think it's fair to say, was not happy about that.

Micah Loewinger: Earl wanted to talk about appealing the decision. He went to speak with the top in-house New York Times lawyer, chief counsel, James Goodell.

Earl: Goodell is shaking his finger in my face saying, "You keep pushing this and what's going to happen is you're going to get some bad law written and reporters will be suffering for a lot of years under this." Then I said, "I'm not pushing anything, it's the Justice Department that's pushing it," but he tried to put it on me.

Micah Loewinger: This conversation turned out to be prescient. At first, everything seemed to be going well for Earl and his legal team.

Lee Levine: Lo and behold, the Court of Appeals agreed with Earl and ruled that he didn't even have to appear before the grand jury.

Micah Loewinger: This was a unanimous decision, right?

Lee Levine: Yes. Unanimous decision.

Micah Loewinger: So the government appeals?

Lee Levine: Yes, the government seeks review in the Supreme Court, and at the same time, there are these other cases lending their way through the courts.

Micah Loewinger: Paul Pappas.

Lee Levine: Television reporter in Massachusetts.

Micah Loewinger: Had also tried to fight a subpoena related to his reporting on the Black Panthers. Then there was Paul Branzburg, a reporter in Kentucky who refused to appear before a grand jury to discuss two sources he had witnessed making marijuana products.

Lee Levine: All three of those cases were ultimately taken to the Supreme Court for review.

Micah Loewinger: They were all rolled up into a single case known today as Branzburg v. Hayes, since the case that comes up first alphabetically in the group often becomes the shorthand name. But United States v. Coldwell was considered the most significant of the three. Earl thought that the mostly liberal court at that time would deliver them a 5-4 win.

Lee Levine: Unluckily, for Earl and the other reporters, there was a dramatic change in the court's composition.

Male Speaker: The White House announced this evening that Justice Hugo L. Black, the oldest member of the Supreme Court, has retired from the bench.

Male Speaker: Associate Justice John Marshall Harlan, turned in his resignation today, just six days after the resignation of Justice Hugo Black.

Micah Loewinger: Allowing President Richard Nixon to appoint two new justices to the bench.

Male Speaker: The US Supreme Court today took on the kind of conservative weight sought so long by Mr. Nixon. It did so by reaching its full complement of nine members, with a swearing in of Justices Lewis Pollard Jr. and William Rehnquist.

Lee Levine: Justice Rehnquist came to the court from the Justice Department, and while in the Justice Department, one of his jobs, as head of the Office of Legal Council, was to formulate the administration's position with respect to this very issue.

Earl: Everybody just assumed he would recuse himself, and he did. He was sitting right there.

Micah Loewinger: Why didn't he recuse himself?

Lee Levine: I don't know. [laughs] I suppose he wanted to rule on the case and didn't think he had a conflict. Just like today, with uproarers over Justice Thomas ruling on cases that some people think he shouldn't. There's really nothing that can be done about it.

Micah Loewinger: On June 29, 1972, the court voted 5-4 against the reporters with Justice Rehnquist casting one of the deciding votes.

Earl: Justice White, wrote for the majority, wrote that this whole concept of indirect restraints was bogus. Then Justice Powell, newly on the court, wrote an opinion concurring in Justice White's opinion, but adding a few words of his own. His opinion has been characterized over the years as enigmatic, because it seems to suggest although not entirely clearly, that there are circumstances in which, on a case-by-case basis, a reporter would be able to successfully refuse to answer questions posed by a grand jury.

Micah Loewinger: This enigmatic opinion by Justice Powell would turn out to have a long after life, which we'll get to in a minute.

Lee Levine: After the Supreme Court's decision, Earl never have heard another word from the government. He was never called the testify. There's an argument that the government accomplished what it wanted to accomplish, which is that it had established a precedent that would make sources in the future reluctant to talk to journalists.

Earl: The Supreme Court said, yes, the government can force you to be a spy and that if you resist, you'll go to jail.

Micah Loewinger: Here's Earl speaking with CBS in 1973.

Earl: I honestly don't believe that it's possible to do effective journalism in America now.

Lee Levine: Well, let me say this, an immediate aftermath of the decision, they were the kinds of editorials you would expect in newspapers all over the country.

Micah Loewinger: Yes, there was a kind of freak out.

Lee Levine: Yes.

Male Speaker: Editors at The New York Times are worried about the effects of the Supreme Court's decision. National editor, Jean Roberts says his staff reporters are already jittering.

Micah Loewinger: After the trial, Earl testified before Congress advocating for a federal shield law.

Earl: Only when we can operate in an atmosphere free of the intimidation of government, can we assure the public that we are vigorously investigating all phases of corruption and political [unintelligible 00:33:58].

Micah Loewinger: Lawmakers from both parties were listening, they discussed two kinds of bills, laws that would provide absolute immunity, no revealing of anonymous sources, no testifying before grand juries, period, or a qualified immunity, which would only require outing sources if three criteria are met.

Lee Levine: One would be that the information sought from the reporter is relevant to an alleged crime. Second, that there's an overriding national interest involved, and third, and this is really the kicker in it, that it can be obtained that information from the reporter and no other source.

Micah Loewinger: The issue is that news outlets were split on the question of qualified versus absolute immunity. They just couldn't agree. As a result, the federal shield law died on the vine.

Lee Levine: The one constructive thing that came out of it was that Jim Goodell-

Micah Loewinger: The New York Times General Counsel, who allegedly wagged his finger at Earl-

Lee Levine: -to his great and everlasting credit, decided that he should take Justice Powell's admittedly enigmatic language and pour meaning into it. Over the next several decades, Jim took the lead and was instrumental in having virtually every federal court of appeals and virtually every state Supreme Court hold that, in fact, there is the qualified First Amendment-based reporter's privilege, and that it operates in every kind of legal proceeding with the one exception of grand juries.

Micah Loewinger: In other words, Goodell, and his fellow media lawyers successfully pointed to the Caldwell Branzburg ruling to shield reporters from the judicial system. Despite this, several writers over the years have been forced to choose prison over revealing sources to a grand jury.

Male Speaker: Judith Miller was jailed for 85 days.

Male Speaker: Vanessa Leggett was jailed for refusing to give up her materials to the government.

Male Speaker: Josh Wolf, longest jail journalist for protecting a source in US history.

Micah Loewinger: Towards the end of my conversation with Lee Levine, he told me he was pretty sure I could have gotten out of participating in the January 6th case. That I could have fought the subpoena in court and won, which honestly came as a shock, and I think he could tell.

Lee Levine: Let me say this, it will make you feel better. [laughs] Just a few years before this, during the first phase of the Civil Rights Movement in the South, where reporters were witnessing the clan engaging in violence and doing all other sorts of despicable things, many reporters were more than happy to share what they knew and saw and heard with the FBI. Nobody thought anything about it.

Micah Loewinger: This past October, Attorney General Merrick Garland announced a new written policy at the DOJ. That the department would limit the circumstances in which prosecutors can subpoena journalists for their reporting materials. Of course, a policy unlike a law can be easily undone by the next administration or the next. Congress needs to pass a federal shield law, like the Protect Reporters from Excessive State Suppression, aka the PRESS Act, which Representative Jamie Raskin discussed on the House floor last September.

Jamie Raskin: I'm very hopeful that this is the Congress in which we can get it done.

Micah Loewinger: It wasn't. The House bill passed, but the Senate bill never left the Judiciary Committee. Representative Raskin told me he intends to reintroduce the PRESS Act this summer. This is a basic protection for journalism. We should have codified it 50 years ago, and we need to pass it now.

[music]

Brooke Gladstone: Coming up, Micah goes to Montana to investigate the origins of the Oath Keepers. This is On The Media.