Broken Promise

BOB GARFIELD From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media. I'm Bob Garfield. This week, a House committee is voting on whether to admit Puerto Rico as a state. But Puerto Ricans have been here before.

[CLIP]

ADVERTISEMENT This is Puerto Rico. Progress Island, USA

YARIMAR BONILLA Kind of reminds me of the Seinfeld episode where George Costanza tells the parents of his deceased fiancé that he has a house in the Hamptons, and they know it's not true.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT This plebiscite is at best only a temporary solution. The United States is not legally bound by its results, and neither is Puerto Rico.

NOEL ALGARIN The only place where we can call ourselves sovereign is in sports. In sports, we get to be someone.

JULIO RICARDO VARELA Right here, baby. Right here, Carlos, Carlitos!

SPORTS ANNOUNCER Fight for the rebound. Here comes the roar!

JULIO RICARDO VARELA Carlito!

YARIMAR BONILLA We've been in a car with the United States, headed to the Hamptons when we all know there's no house in the Hamptons, you know?

[LAUGHTER]

BOB GARFIELD It's all coming up, after this.

ALANA CASANOVA-BURGESS Hi, I'm Alana Casanova-Burgess. And I've got a quick note before we get to this week's On the Media. I'm the host of a podcast called La Brega: Stories of the Puerto Rican Experience. You've been hearing some of the episodes of La Brega on the On the Media feed. And that's because really, On The Media made the show possible. It's really an experiment in creating the kind of coverage, producing the kind of storytelling that puts the audience first. That tries to do justice to a place that a lot of the mainstream media gets wrong or just doesn't get at all. And by the way, we made the series in both English and Spanish, so we wouldn't leave anybody out. There's really nothing else like it. And I can tell you, La Brega wouldn't exist if the team here at On the Media and WNYC didn't say: "hey, these are stories that really need to get reported out. It's got to get made. Let's do it." And the majority of our funding here at WNYC Studios comes from you, our listeners. So, thank you. To support OTM and projects like La Brega, all you have to do is text the letters OTM to 70101, you'll get a text back with a link where you can make a quick donation or visit onthemedia.org and click donate. Thank you so much for your support. It's what makes our work possible. Gracias.

[BREAK]

BOB GARFIELD From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media, I'm Bob Garfield.

BROOKE GLADSTONE And I'm Brooke Gladstone. Last month, many Puerto Ricans were incensed by spring breakers and other visitors who flouted local rules imposed to reduce the spread of covid-19. Puerto Rico was one of the first U.S. jurisdictions to issue a mask mandate, and it maintains strict curfews. The pandemic wasn't politicized, and when it arrived amid earthquakes in the South and the protracted efforts to rebuild after Hurricane Maria, Puerto Rico's fragile health care system was still able to cope. Tourists are always welcome, but as one local told NBC News, people can't come here and act as if the virus doesn't exist. They have a sense of entitlement and apathy I don't understand. For the mainland, the island has long been a locus of both entitlement and apathy. But next week, politicians, some of them anyway, will be paying attention. On April 14th, Wednesday at 1 p.m. Eastern Time, the National Resources Committee, which oversees territorial affairs, will consider two competing bills. One would provide for the admission of Puerto Rico as a state. The other would provide for true self-determination. Either would be historic. Both are deeply opposed by the GOP. There's also a rich history of division within Puerto Rico over what its status should be, but most agree that the current situation, this disenfranchised limbo, isn't it? OTM producer Alana Casanova-Burgess also is host of the La Brega podcast produced by WNYC and Futuro Studios. And in this episode, La Brega offers up some insight into that part of American history that the mainland mostly doesn't know and needs to understand. Here's Alana.

ALANA CASANOVA-BURGESS I've noticed that outside of Puerto Rico, many people seem uncomfortable calling the island a U.S. colony. In English, you'll hear the word territory or Commonwealth, protectorate even. And that used to be the case in Puerto Rico, too, but not anymore.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT Hay muchos en Puerto Rico, muchos, muchos, aun dentro de su partido, que dicen que si que Puerto Rico es una colonia, por eso, es que se llama de descolonizacíon. [END CLIP]

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT Eso es ser una colonia completamente. [END CLIP]

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT Por que Puerto Rico es una colonia de los Estados Unidos. [END CLIP]

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT no sea una colonia. [END CLIP]

ALANA CASANOVA-BURGESS People would twist themselves into pretzels to avoid the C word. And there's a reason for that.

YARIMAR BONILLA Puerto Ricans were promised that they were not a colony.

ALANA CASANOVA-BURGESS This is Yarimar Bonilla. Yarimar is a political anthropologist. She has a column in the Puerto Rican newspaper, El Nuevo Dia, and she's also written for outlets like The Washington Post and The Nation. That promise that Yarimar mentioned, about not being a colony, it's pretty much been broken. In 1952, Puerto Rico had adopted this new political status called the ELA, the Estado Libre Asociado, or free-associated state, which doesn't really mean much. In English, we call it a commonwealth. And what does that mean? Is it like the Commonwealth of Massachusetts? No. Is it like the Commonwealth of Canada? Also, no. Commonwealth doesn't really mean anything concrete, but it's the kind of word that made everyone feel better about the US having a colony. The Estado Libre Asociado, the ELA, promised self-governance, but not independence. It was a kind of compromise created by the island's first elected governor, Luis Muñoz Marín in order to massage the continued colonial interests of the U.S. and Puerto Rico and present a sovereign future to his residents, Marín came up with this label that sounded like decolonization.

YARIMAR BONILLA He thought that like since it had all this language of decolonization. He thought that he could set legal precedents to kind of if you build it, they will come. Like if you build it, they will decolonize - kind of idea. And then meanwhile, the United States, they're like, well, we're going to pretend that we're decolonizing, but we're not really going to decolonize. So, it's like both parts were kind of calling each other on their bluff. It kind of reminds me of this like Seinfeld episode that I love where like George Costanza meets up with the parents of his deceased fiance and he tells them he has a house in the Hamptons and they know it's not true

[CLIP]

GEORGE COSTANZA It's a two-hour drive. Once you get in that car, we are going all the way...

[DOOR SLAMS].

GEORGE COSTANZA...to the Hamptons [END CLIP]

YARIMAR BONILLA And they all get into a car and start driving to the Hamptons.

[ALANA CHUCKLES].

YARIMAR BONILLA And they also all know that the others know that it's all a farce.

[CLIP]

GEORGE COSTANZA Almost there.

FATHER IN LAW Now this is the end of Long Island. Where's your house?

GEORGE COSTANZA We go on foot from here.

FATHER IN LAW All right. [END CLIP]

YARIMAR BONILLA So basically, like we've been in a car with the United States, headed to the Hamptons, when we all know there's no house in the Hamptons. You know?

[BOTH CHUCKLE]

ALANA CASANOVA-BURGESS There's some indication that Luis Muñoz Marín and the U.S. Congress both knew there was no House in the Hamptons. In 1950, while testifying in a House committee hearing, he said, quote, If the people of Puerto Rico should go crazy, Congress can always get around and legislate again. That's what he said in Washington, D.C. But in Puerto Rico, he claimed this new status would be a definitive end, to quote, every trace of colonialism. Part of the promise of the ELA was that it was supposedly the best of both worlds. Self-governance with the protection of the U.S. military, and the mobility of a U.S. passport. It was also imagined as a key to prosperity, having a link to the wealthy U.S. while also being able to manage our own affairs. But that was 70 years ago, and recently this idea has been dealt some severe blows. 15 years ago, a recession became a debt crisis, which is now an austerity crisis. Then in 2016, during 2 Supreme Court hearings, the US government itself pushed the argument that Puerto Rico wasn't really sovereign after all. The next nail in the coffin came in 2016. It was a law named unironically, Ley Promesa, or promise. That's the federal law that installed a fiscal control board to manage the island's finances and implement austerity policies in order to service the debt. These series of events created an awakening. In response to the Promesa Law, protesters declared that the time of the promises was over.

[SINGING]

ALANA CASANOVA-BURGESS Se acabaron las promesas, the ELA had been a lie. Something between Puerto Rico and the U.S. had been broken.

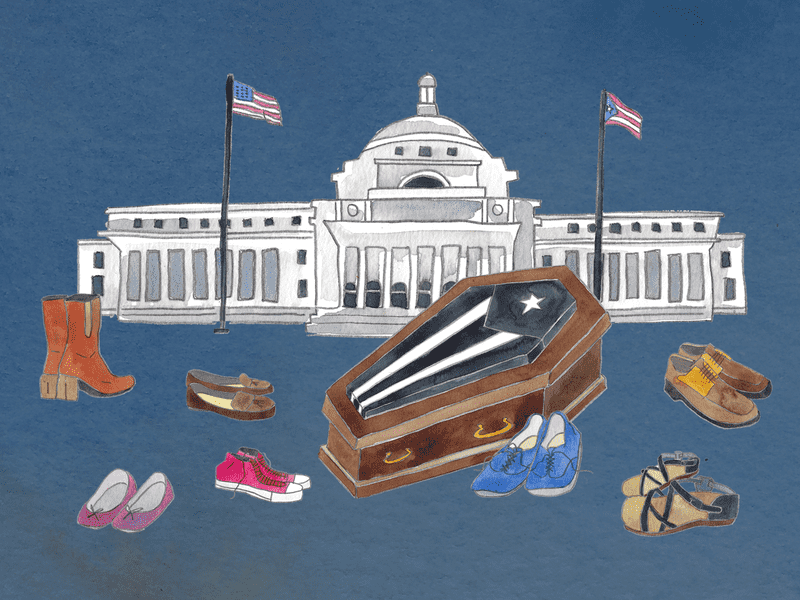

YARIMAR BONILLA After all these revelations, people started talking about the death of the ELA, the death of the Commonwealth, and I became really fascinated by that idea. Like what does it mean for a political project to die?

ALANA CASANOVA-BURGESS In what some called a sign of mourning, black and white Puerto Rican flags started popping up, instead of the red, white and blue one. There were murals denouncing colonialism, too. And then came the deaths from Maria. Not metaphorical, not performative, but thousands of lives lost in the aftermath. And here here is where maybe Puerto Rico could have used the benefits of the island's murky relationship with the U.S. to rebuild from the hurricane. Instead, President Trump threw his infamous paper towels and the White House slow walked funds. Leaving many residents without electricity for nearly a year. Some people are still living under tarps, 3 years later.

YARIMAR BONILLA Who feels decolonized in Puerto Rico, and who’s like we're good? I want to start at the beginning. I want to think about what was the ELA promise to be and who believed in that promise. Who said we had a house in the Hamptons?

ALANA CASANOVA-BURGESS Yarimar decided to start right at home, with her grandmother.

MONSY [SINGING] Ay, ay, ay, ay, canta y no llores...

YARIMAR BONILLA That voice you hear is my 93 year old grandmother, Maria Monserrate Fuentes Gerena, better known as Monsy. She loves to sing. In fact, it's hard to get her to stop singing.

MONSY [SINGING] Acercate mas, y mas...

YARIMAR BONILLA Like many Puerto Ricans. I grew up very close to my grandmother. She was always around telling me to fix my hair, asking me if I was really going to go out dressed like that and basically helping raise me along with my mother. During the pandemic, we spent lots of time joking around and filming funny videos for Instagram where her handle is Badmonsy.

YARIMAR, MONSY, YARIMAR's MOM [SINGING] Me levanté contento...

YARIMAR BONILLA This is us, with my mom, singing Bad Bunny.

YARIMAR, MONSY, YARIMAR's MOM por que dicen por ahi que están hablando de mi. Que se joda, que se joda, que se joda....

YARIMAR BONILLA No joke, my grandma really does love Bad Bunny.

MONSY Él hablo malo pero actúa bien.

YARIMAR BONILLA She thinks he has a potty mouth but a good heart.

MONSY Ay a mi encanta Bad Bunny! A mi encanta él.

YARIMAR BONILLA The pandemic has also given me a chance to discover her surprising brushes with history.

MONSY Yo fui a un cumpleaños de Munoz Marín. Yo te lo dije.

YARIMAR BONILLA It turns out she had gone to a birthday party for none other than Gobernador Luis Munoz Marin. She was invited by a suitor who coyly asked if she’d like to join him at a birthday function. When he explained who the party was for, she lost it.

MONSY Yo: que que? Yo me volví loca.

YARIMAR BONILLA I asked her what she wore to the special occasion. And unsurprisingly, she dressed in red. The color of Munoz's party. She wore a bright red pantsuit and a pava, the straw hat traditionally worn by Puerto Rican peasants. This was her homage to the color and symbol of Munoz's party. The populares. She's bummed that there weren't cell phones back then so she could have a picture, not just of her slammin outfit, but of this historic encounter.

[CLIP]

ANTHEM Jalda arriba va cantando Popular, jalda arriba siempre alegre, va riendo [END CLIP]

YARIMAR BONILLA What she remembers most fondly about those times is the conviction and commitment of the political leaders.

MONSY Ramos Antonini.

YARIMAR BONILLA She fondly remembers Mr. Ramos Antonini, the well-known black socialist lawyer who is one of the founders of the party. But her favorite, of course, was Luis Muñoz Marín. Just looking at him, she says, inspired confidence. She loves to talk about how he would go to the chozas of the jibaros. Homes with dirt floors and few belongings and have coffee with the residents in the little cups they fashioned out of hollowed out coconuts.

MONSY Él decia que sabía mejor ahi el café

YARIMAR BONILLA He swore the coconut cups made the coffee taste even better. Every time she tells the story, something about that small gesture of grace really gets to her. She's convinced that he really did love Puerto Rico and just wanted the best for it.

MONSY Él sentia, amaba a Puerto Rico, él lo amaba.

YARIMAR BONILLA This kind of uncritical nostalgia is a common staple among Puerto Rican abuelitas. But actually, Luis Muñoz Marín did a lot to erase rural life through his emphasis on industrial development. But for my grandmother, it was all about eradicating the poverty that she grew up with. Bread, land and liberty. That was the promise, and my grandmother believed in it because she saw it with her own eyes. Lands were being massively redistributed, even her uncle got a parcel. During this time, industry was also arriving. Homes and schools were being built.

MONSY Y siguió mejorando y siguió mejorando.

YARIMAR BONILLA For my grandmother, everything was getting better and better. The ELA really did seem like the best we could hope for. The best of all possible worlds.

DEEPAK LAMBA NIEVES The people of Puerto Rico felt – hey, el ELA, lo mejor de los mundos.

YARIMAR BONILLA This is Deepak Lamba Nieves. He's a development planner at the Center for a New Economy, and a good friend. Deepak argues that the ELA was never really about decolonizing Puerto Rico. It was about using Puerto Rico as an economic experiment as a counterpoint to communism during the Cold War

[CLIP]

ADVERTISEMENT Apartment complexes, bilingual schools, modern hospitals, luxury hotels, progress can be seen everywhere. This is Puerto Rico, Progress Island, USA. [END CLIP]

YARIMAR BONILLA To the outside, the ELA was sold as an economic success story, but all that economic growth was built on unsustainable compromises. From the beginning, there was an overreliance on tax incentives which Washington could enact and take away as it pleased. Once the tax incentives were taken away, companies started fleeing Puerto Rico and the government took on massive debt to stay afloat. By 2016, it became clear that Puerto Rico was descending into what economists literally call a death spiral. Everyone began putting pressure on Washington to pass some kind of debt relief. Among those making the rounds on Capitol Hill was Deepak. He thought...

DEEPAK LAMBA NIEVES Hey, there's another way of addressing the Puerto Rican dilemma with the economic situation and also the debt issue.

YARIMAR BONILLA He was initially confident about the impact he could have. He assumed he would be taken seriously. After all, he's a smart guy who works at a fancy think tank where they had developed a solid, cost effective plan. But Washington politicians had no time for him. Deepak says they made him feel like he was begging for a handout– or worse, praying for mercy. He returned from D.C., convinced that Puerto Rico was quite simply a colony, and that the island just doesn't matter to the United States. If you read a news story about Puerto Rico's debt crisis, you will most likely see it accompanied by a picture of desolate Paseo de Diego. This pedestrian mall used to be a bustling commercial district. Visitors from surrounding parts of the Caribbean would come and load up on goods to sell back home. My mom was a master seamstress. Every year we would do her back to school shopping. Happily combing through the big bolts of fabric at stores like La Riviera, where we would purchase fabric for a whole semester's worth of new handmade dresses. Now, that's a long-lost memory. Most of those stores are shuttered, and the few that remain are struggling to survive.

[MUSIC PLAYING FROM CARAVANA]

YARIMAR BONILLA Alana and I were recently Rio Piedras at a time when it felt much more active. There was a Caravana – a political rally where people get in their cars and drive around following a candidate during election season. We were asking folks there if the ELA had died, and one guy was quick to answer.

[CLIP]

MAN Él ELA un engaño. No murió, ni siquiera nunca nacío [END CLIP]

YARIMAR BONILLA It never died, he said, because it was never born. He was there supporting a new movement in Puerto Rico that wants to stop talking about status and focus on other fundamental issues like government corruption, gender violence and the need to audit the debt. The Caravana was for the campaign of a young politician named Manuel Natal. That he narrowly lost the race to be San Juan's mayor, but even this near victory was astonishing, given that Natal is from a brand-new political party.

[CLIP]

YARIMAR So how would you define the ELA?

NATAL It was, el maquillaje de la colonia? It was a way of putting a little bit of makeup [CHUCKLES] on our colonial relationship with the United States.

YARIMAR A little lipstick on the pig?

NATAL Yeah [CHUCKLES] the pig is the colony, not the people of Puerto Rico

YARIMAR That's good! [END CLIP]

YARIMAR BONILLA Natal actually used to really believe in the ELA. He comes from a family of Populares and was once a rising star in the party. But a few years ago, he made a radical decision and became an independent, citing corruption among his colleagues. Then, along with other progressive leaders, he helped found a new political party called: Movimiento Victoria Ciudadana. Its members have different visions. Many are pro-independence, but some are pro-statehood and others, like Natal, are soberanistas, meaning they want more local sovereignty while still retaining their ties to the U.S.. But they all agree on one thing – decolonization is necessary, and we need a new process for deciding which status we want. For decades, the political parties in Puerto Rico have been organized around status options, and every couple of years we undergo these performative votes that are described as plebiscites or referendums. Back in the late 60s, when NBC was reporting on the first plebiscite vote, they called out, right away, the irony of the spectacle,

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT Most Puerto Ricans, even those who favor a commonwealth, agree on one thing. This plebiscite is at best only a temporary solution. The United States is not legally bound by its results, and neither is Puerto Rico.

YARIMAR BONILLA At best, these are little more than opinion polls. In the most recent one, last November, the statehood option won by a slim margin, receiving 52 percent of the votes cast. But these plebiscites are non-binding. They're not tied to any legislation and have no support in Washington. They're basically another bluff. It's like once again, we're getting in a car heading for the Hamptons.

NATAL So what are our other alternatives?

YARIMAR BONILLA Natal's party proposes what they call a constitutional assembly. In which representatives of each political option could negotiate directly with Washington, the terms of each status choice. And what would this do? Ideally, it would bring concrete answers to enduring questions like would we have dual citizenship if we were independent? Would we have access to federal programs like Pell Grants as an associated republic? And maybe the most delicate question, but also the most important one, would any of these options be tied to reparations, for over 120 years of colonial rule? I started the pandemic posting videos of my grandmother on social media, joking that she was la influencer, but by the time the political campaigns were in full swing, she had become a bona fide social media sensation.

MONSY Dime hija.

YARIMAR BONILLA ¿Por quien vas a votar?

MONSY Pues, yo quiero un cambio, pero un cambio radical.

YARIMAR BONILLA radical?

MONSY radical.

YARIMAR BONILLA I posted a video of her in a rocking chair, where I asked her how she was going to vote this time around. She surprised us all by saying that she supported the pro-independence candidate, Juan Dalmau. The conventional wisdom was that only young voters were supporting the alternative candidates like Natal and Dalmau, and that older voters were afraid of change. Her video went viral. Dalmau even used it for one of his TV spots, and then the morning shows came calling.

[CLIP]

NEWS REPORT Como todo una influencer, como Bad Monsy ha conquistado las redes sociales por sus videos. [END CLIP]

YARIMAR BONILLA She then wrote and sang a political song that also took off:

MONSY [SINGING] Ni azules ni colora’os, ni azules ni colora’os. Yo quiero la patria nueva que nos propone Dalmau! [HOST LAIGHS],

YARIMAR BONILLA And the weekend before the election, then Mao himself actually came to visit her and brought her flowers, which put her over the moon.

MONSY No lo puedo [unintelligible]!

YARIMAR BONILLA After a lifetime of voting for the Populares and of supporting the ELA, her public support of an independentista was surprising, but it doesn't mean that she wants independence itself.

MONSY No, no independencia por ahora

YARIMAR BONILLA She told me she voted for Dalmau, simply because she thought he would make a good governor. As far as the status, she felt like that could be dealt with later.

MONSY Entonces despues se podia bregar con lo otro. Tu sabes? Poco a poco.

YARIMAR BONILLA Like a good popular, she thinks we should just kick the status can down the road. But you know who is really kicking the can down the road, really hard all the time? The U.S. Congress, they refused to commit to anything or to even speak clearly about why it insists on keeping Puerto Rico as an ambiguous transition land. So where does that leave us? Honestly, I don't know. But I'm skeptical of all the options currently on the table. For example, when I consider independence, I get excited about the possibility of being our own country. But then I look around at our neighbors in the Caribbean and see that many have the same challenges as Puerto Rico, indebted economies, austerity regimes, huge diasporas, the challenges of disaster recovery and battles over corruption. Independence is clearly not a silver bullet. It doesn't guarantee sovereignty. Instead of battling the fiscal control board, we might end up battling the World Bank or the IMF. But when I consider statehood, I think of Hawaii and how the native population there was shut out of much of the prosperity and development that statehood supposedly ushered in. Or I look at the movement for black lives in the U.S. and the discrimination suffered by people of color in the States. And it makes me wonder if anything other than second class citizenship will ever be available to us. So, I end up back where we've been for all these years – at an impasse. Yet something feels different about the current moment. The signs of change might be subtle, but they're there. In the ubiquity of the black and white protest flags, in the dark lyrics of a Bad Bunny song, and in the transformations at the ballot box as thousands moved towards alternative candidates. So perhaps if the death of the ELA and the end of the promises means anything, it's the realization that the world we deserve is not something that can be promised, conceded or guaranteed, but it's also not something that we can keep waiting for.

[PROTEST CHANTING & MUSIC]

BOB GARFIELD Coming up, that one-time Puerto Rico absolutely owned the U.S.... In basketball,

BROOKE GLADSTONE This is On the Media.

[BREAK]

BROOKE GLADSTONE This is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone.

BOB GARFIELD And I'm Bob Garfield. As we learned before the break, there are movements for and against independence in Puerto Rico. But in the meantime, the island stays in limbo with representatives in the United States Congress, but no say in who becomes president and many other such indignities. However, there is at least one international body that considers the island its own sovereign nation, and that is the International Olympic Committee, which has exclusive authority to determine which states count as countries for the purposes of Olympic law. And the IOC regards Puerto Rico as a country. And that's how the stage came to be set for one of the most epic showdowns in the island's sporting history. Here's Alana.

ALANA CASANOVA-BURGESS Without a doubt, there is a deep connection between being Puerto Rican and rooting for our sports teams. And yes, people all over the world love sports and are proud of their athletes. But in Puerto Rico, the stakes are just higher because Puerto Rico, despite being a U.S. colony, competes in international sporting events like the Olympics on its own, under its own flag, as if we were an independent country. Journalist Noel Algarin, who has covered sports in Puerto Rico for many years, put it this way.

NOEL ALGARIN The only place where we can call ourselves sovereign, is in sports. In sports, we get to be someone and then we get chances in a more symbolic way to face the country that owns you in some way.

ALANA CASANOVA-BURGESS We're going to tell a story about one of those chances. A time when Puerto Rico faced off against the United States in basketball on the sporting world's largest stage. Journalist Julio Ricardo Varela was born in Puerto Rico and grew up there, but when he was in first grade, he moved with his mom to the Bronx and would go back and forth to the island over the years. But he never had any doubt as to who his team was. It was always Puerto Rico.

JULIO RICARDO VARELA Flor Meléndez was a coach of the team.

FLOR MELENDEZ Bueno, mi nombre es Flor Meléndez.

JULIO RICARDO VARELA And he was a legend in Puerto Rico.

[CLIP]

SPORTS ANNOUNCER [unintelligible] loco, piensen en lo que tenemos que hacer [END CLIP].

JULIO RICARDO VARELA In a documentary about the 1979 games, you can see him screaming at players and gesturing wildly. He's looking really sharp with this thick black mustache and 'fro. Flor went on to become one of the national team's all-time most decorated coaches. And his story kind of runs parallel to the story of Puerto Rican basketball. So, Flor grew up in a big family

FLOR MELENDEZ 11 hermanos

JULIO RICARDO VARELA the oldest of 11 siblings, they lived in public housing.

FLOR MELENDEZ Caserio publicó

JULIO RICARDO VARELA We're talking 1960. Flor started playing basketball at his local YMCA, then as a teenager, he played in the Puerto Rican League and pretty early on, Flor figured he had a talent for coaching. He described his coaching style as

FLOR MELENDEZ Fuerte.

JULIO RICARDO VARELA Tough.

FLOR MELENDEZ Yo soy una persona que me gusta la disciplina

JULIO RICARDO VARELA Discipline heavy. And Flor got into coaching right around this kind of magic moment for Puerto Rican basketball. Coaches like Flor started visiting New York City and scouring the courts where Nuyoricans were playing street ball, and they started convincing these players to leave their lives behind to come play professionally in Puerto Rico. Here are these amazing Afro-Puerto Ricans who learn the craft in the Mecca of the sport and brought it back.

[CLIP]

SPORTS ANNOUNCER favorece a Raymond Dalmau, que lo empato, la jugada última

JULIO RICARDO VARELA It was a different kind of basketball and people were used to Puerto Rico. It was a faster rhythm of play with big dunks, and it was fun. Like that type of basketball is fun. These were the boom years for Puerto Rican basketball. And as the team kept winning and becoming better basketball in Puerto Rico became the sport. Fans filled the stadiums. By the 90s, many from that generation of great Nuyorican players had retired, but they had inspired a new wave of Puerto Rican born players, and those players, they took the team to even greater heights.

[CLIP]

SPORTS ANNOUNCER ¡Está ganando Puerto Rico! [END CLIP]

[CLIP]

SPORTS ANNOUNCER undecimos juegos Panamericanos. [END CLIP]

JULIO RICARDO VARELA Gold in the 1991 Pan American Games, Gold in the 1993 Central American Games, and maybe the biggest accomplishment of all, fourth place in the 1990 world championships. Puerto Rico, the fourth best team in the world. That's pretty good. With Puerto Rico having made a name for itself on the international stage, Flor Melendez got opportunities to coach in Argentina and Panama. But it was always clear to him that coaching the Puerto Rican national team, that was a different kind of responsibility.

FLOR MELENDEZ Yo tengo un dicho que...

JULIO RICARDO VARELA He has this saying...

FLOR MELENDEZ La bola de baloncesto es el arma...nosotros no tenemos ejército.

JULIO RICARDO VARELA He thinks about it like this. Puerto Rico doesn't have an army. So we, the national basketball team, we are the ones that have to represent the country. He says that the basketball is a weapon and the basketball jersey is actually a soldier's uniform. It's like you respect it, like you respect a flag. He told me he had this ritual he would do with the national team. That at the season's first practice, where they would put on their national team jerseys for the first time

FLOR MELENDEZ pues yo – yo le entregaba....

JULIO RICARDO VARELA He'd go down the line and hand out little Puerto Rican flag pins to all the players. He says the players would get so emotional about it. And whenever they'd face the United States in international play, those games had a special kind of weight. It was the chance for his soldiers to go to war.

FLOR MELENDEZ Es la guerra, la guerra, la guerra, la guerra, la guerra...

JULIO RICARDO VARELA The war we haven't been able to have to win our independence, he says.

[FLOR LAUGHS].

JULIO RICARDO VARELA Puerto Rico is generally pretty outgunned in this war. The U.S., after all, was and is the global superpower of basketball, especially after the 1992 Barcelona Olympics. What happened was a few years before the International Basketball Federation made a change to their rules to allow NBA players in international competitions. And that change was huge.

[CLIP]

SPORTS ANNOUNCER This summer, the U.S. Olympic basketball team will make history. The dream team of Jordan, Bird, Ewing, Robinson, Pippen, Drexler, Mullin Barkley, Magic. [END CLIP]

JULIO RICARDO VARELA That first dream team that went to Barcelona in 1992 was legendary.

[CLIP]

SPORTS ANNOUNCER This collection of superstars has been unselfishly magnificent. [END CLIP]

JULIO RICARDO VARELA It wasn't just a sports team. It was a cultural phenomenon.

[CLIP]

ANNOUNCER You've got yourself the gold medal meal.

ATHLETE What you want, is what you get.

CHORUS At McDonald's today.

ATHLETE Gold medal? It's in the bag [END CLIP]

JULIO RICARDO VARELA And they kicked everybody's ass. It wasn't even close. It wasn't even fun to watch. They were that good.

[CLIP]

OLYMPIC ANNOUNCER And there it is. And the dream team, win gold. [END CLIP]

JULIO RICARDO VARELA And from then on, the players change, but the dream team was here to stay. The U.S. won gold again in 1996 at the Atlanta Olympics.

[CLIP]

OLYMPIC ANNOUNCER The United States has won the gold. [END CLIP]

JULIO RICARDO VARELA In 2000 at the Sydney Olympics. Same story.

[CLIP]

OLYMPIC ANNOUNCER And it's all smiles now from Dream Team 4. [END CLIP]

JULIO RICARDO VARELA And then you get to the 2004 Olympics in Athens. And the U.S. team was an institution at that point. And the first game they were going to play that Olympics was with Puerto Rico.

The 2004 team was stacked. Alan Iverson, A.I, Dwayne Wade, D Wade, Tim Duncan, one of my favorite players of all time. I mean, the team even had LeBron James in his early days. LeBron James! These guys were invincible in the Olympics. I mean that literally. Since NBA players were allowed to play, they had never lost an Olympic game. They were the Death Star, and if the U.S. team was the Death Star, the Puerto Rico team was definitely the ragtag Rebel Alliance. The players were mostly local stars from the Baloncesto Superior Nacional, the League in Puerto Rico. You had José Ortiz, also known as Piculin.

[CLIP]

SPORTS ANNOUNCER Alli esta apuntalo para Piculin!

JULIO CESAR TORRES Oh, that's their leader. The rock, the legend [END CLIP]

JULIO RICARDO VARELA That's Julio César Torres. He's the filmmaker behind a great Puerto Rican basketball documentary called Nuyorican Basket. You had Eddie Cassiano

[CLIP]

JULIO CESAR TORRES Eddie man, Eddie was the firecracker. He will go toe to toe with you. And if he had to fight, he will fight.

SPORTS ANNOUNCER McGrady and Cassiano going nose to nose. [END CLIP]

JULIO RICARDO VARELA Rolando Hourruitiner.

[CLIP]

JULIO CESAR TORRES He was all about the craft. Very disciplined, and a great defender [END CLIP]

JULIO RICARDO VARELA And a lot of other really talented guys: Larry Ayuso, Bobby Joe Hatton, and then there was Carlos Arroyo.

[CLIP]

JUILO CESAR TORRES Carlos Arroyo was the young gun.

SPORTS ANNOUNCER Arroyo por el cristal...con el primer canasto de la noche.

JULIO CESAR TORRES Anxious to prove himself with a lot of talent.

SPORTS ANNOUNCER As Arroyo knocks down that jumper. [END CLIP]

JULIO RICARDO VARELA Carlos was in the NBA. He was a starting point guard with the Utah Jazz that season and was on a path to becoming a legend.

[CLIP]

SPORTS ANNOUNCER Arroyo, to the angle right, gets behind tag, shakin and bakin, doubling momentarily – nice – goes up to the hoop...and he's fouled! [END CLIP]

JULIO RICARDO VARELA At 6'2, he was a lot shorter than most other NBA guys, but Carlos was fast and he played with energy and he played with heart. And we all loved him. So, a few weeks before the Olympics, the Puerto Rican team goes to Florida for a week of practice and a series of warm up games against the U.S. team. This is strangely standard practice leading up to these big international competitions. And at these games, they're playing man to man defense, which is what it sounds like. Each player follows a player on the other team and sticks to them. And Puerto Rico, because of their size or lack of it. You know, the Americans are bigger. They were faster. They wanted to play zone defense where you literally stay in a zone and you defend a set area of the court. During one of those games, the American coach went up to the Puerto Rican coaches and asked for a favor.

FLOR MELENDEZ Que por favor, que no le jugaramos...

JULIO RICARDO VARELA He said, can you please not play zone during this game? And it was one of those like, Flor Melendez moments, to be like hmmmm – insert mysterious discovery music – hmmmm. Interesting, they don't want to play against the zone.

FLOR MELENDEZ despues nosotros pues nos quedamos callados.

JULIO RICARDO VARELA He says they kept quiet, and pulled a classic jibaro move.

FLOR MELENDEZ Del jibaro....

JULIO RICARDO VARELA He says whenever city people visit the mountains, they think the jibaros, the country people.

FLOR MELENDEZ que uno no sabe nada.

JULIO RICARDO VARELA Are simpleton's... but secretly, they always have something up their sleeve.

BROOKE GLADSTONE Coming up, the Puerto Rican national basketball team goes to the Olympics. This is On the Media.

[BREAK]

BROOKE GLADSTONE This is On the Media, I'm Brooke Gladstone.

BOB GARFIELD And I'm Bob Garfield. We pick up the story in the summer of 2004, the Puerto Rican national basketball team has arrived in Athens to compete in the Olympics. Journalist Julio Varela takes it from here.

JULIO RICARDO VARELA On the morning of the game in Athens, the Puerto Rican team is expecting the worst. Rolando Houritiner was in his dorm room in the Olympic Village when one of the coaches on the staff, Julio Toro, barged in the room.

[CLIP]

HOURITINER Early in the morning, Julio comes in. It's like, "hey, hey, you guys," "what's going on Julio, it's too early man?" "So, I want you guys to know that we're going to do something different today." "I said what are you talking about?" It's like, "well, you have to wait and see."

JULIO RICARDO VARELA A few hours later, the players are gathered in the locker room, and the coaches bust out their plan. They thought maybe they had found the weakness in the Death Star. They're going to do a variation on the Zone defense that the Americans didn't want to play against, back in Florida, For all you basketball nerds out there, a variation known as a triangle and two defense with the goal of forcing the U.S. team to take outside shots.

[CLIP]

HOURITINER So we looked at each other like, hey, you know, never done it. We lose by 30 every time, so might as well try.

JULIO RICARDO VARELA The game was set to start at eight p.m. Athens time, 1:00 p.m. in Puerto Rico. To jog my memory for this story I recently re-watched the game.

I'm excited. This is the first time I've put this on since 2004. You can see in the broadcast that the arena in Athens was pretty full. Everybody wanted to see the debut of the U.S. team. The whistle blows. The start of the game, it was pretty tight back and forth.

[CLIP]

SPORTS ANNOUNCER The United States leading early by 2. [END CLIP]

JULIO RICARDO VARELA Puerto Rico didn't really start off strong. They just played enough to keep it close.

[CLIP]

SPORTS ANNOUNCER An impressive start for Puerto Rico. [END CLIP]

JULIO RICARDO VARELA I was like, OK, all right, how long is this going to last? This will be entertaining until the U.S. scores like 80 points in a row, and then we're down by 60.

[CLIP]

SPORTS ANNOUNCER There's the buzzer ending the first quarter. [END CLIP]

JULIO RICARDO VARELA But for me, things really kicked off in the second quarter when Carlos Arroyo found Piculin with a super cool pass. Here it comes, here it comes. Look at this pass. Hello. Hello!

[CLIP]

SPORTS ANNOUNCER Carlos Arroyo. Oh, what a ball fake! [END CLIP]

JULIO RICARDO VARELA And then it begins. Something just clicks, and Puerto Rico has this sequence of amazing plays.

[CLIP]

SPORTS ANNOUNCER Excellent ball handling from Carlos Arroyo.

SPORTS ANNOUNCER Body flying all over the place, Arroyo with the steal! [END CLIP]

FLOR MELENDEZ nos daban las cosas, las cosas se nos daban.

JULIO RICARDO VARELA Flor watched Puerto Rican nail shot after shot. He says he noticed the U.S. players in a bad mood, frustrated, and it was probably because the Puerto Rican strategy seemed to be working. Here's Rolando Houritiner.

[CLIP]

HOURITINER We were pretty physical, and we were really giving it to them, you know, and it was something that they were not used to it. And it was our turn to talk trash. "Go ahead and shoot it –You don't want to shoot it, right? Go ahead, shoot it. Let me see it. Let me see your shot, right" [END CLIP]

JULIO RICARDO VARELA As the second quarter ticked down, Puerto Rico's lead just kept growing.

[CLIP]

SPORTS ANNOUNCER It's hard to believe I'm saying this, but the United States trails by 20.

[BUZZER]

And there's the buzzer, ending the first half, a disastrous first half for the United States. [END CLIP]

JULIO RICARDO VARELA At halftime, the score was 49 to 27, 22-point lead for Puerto Rico, and you could see it on the faces of the American coaches. They looked so dejected. Meanwhile, at 1:00 p.m. in Puerto Rico, Hiram Martinez, then a sports editor at El Nuevo Dia, was getting ready to turn on the game when his wife asked him to go to the mall with her to pick something up

[CLIP]

HIRAM Mi esposa queria que... [END CLIP]

JULIO RICARDO VARELA Reluctantly Hiram goes to the mall and finds a store window with the televisions turned to the game.

[CLIP]

HIRAM Como habian 100 personas haciendo lo mismo [END CLIP]

JULIO RICARDO VARELA About 100 people were crowded around doing the same thing. And to Hiram's surprise, Puerto Rico's doing pretty well in the first minutes. But he thinks, who cares? They're just going to come back and slam us. So, he heads back home in the car. When he gets a call from his daughter. Are you watching the game, she asks. Hiram's like, no, why bother? And she says, we're winning. Soon Hiram is getting frantic calls from the newspaper. Where are you? Get over here! We're beating the U.S., and we're beating them good!

[CLIP]

HIRAM Y yo no. No puede ser. [END CLIP]

JULIO RICARDO VARELA Even the Puerto Rican players in the locker room at halftime were surprised at the score. Here's Rolando.

[CLIP]

HOURITINER First of all, my first thought was, wow, I have more pressure now than I did at the beginning of the game. Because it's a brand-new game, 20 brand new minutes. And, you know, they're going to come back stronger. [END CLIP]

JULIO RICARDO VARELA You thought the Americans were going to make a run eventually and come back and beat us. They had to. The third quarter is also really back and forth. The U.S. makes points.

[CLIP]

SPORTS ANNOUNCER Good drive to the basket, pretty move from Allen Iverson. [END CLIP]

JULIO RICARDO VARELA But Puerto Rico maintains its lead.

[CLIP]

SPORTS ANNOUNCER Arroyo inside, and the lead back up to 21. [END CLIP]

JULIO RICARDO VARELA The quarter closes 65-48. Puerto Rico still leading by 17 points. And then the fourth quarter starts. And that's when things get scary. It starts with about 9 minutes left on the clock. Puerto Rico's up by 15...And LeBron James

[CLIP]

SPORTS ANNOUNCER James wide open, and hits the three. LeBron James from downtown and it's a 12-point game. [END CLIP]

JULIO RICARDO VARELA It was the first three for the United States in a long time, and then they just keep making baskets.

[CLIP]

SPORTS ANNOUNCER Lamar Odom cuts the lead to 12, Iverson for 3. Boy, that's a huge bucket. [END CLIP]

JULIO RICARDO VARELA On the court, Rolando watched as Puerto Rico's hard fought lead disappeared from 22 at half time to just 8 points

[CLIP]

HOURITINER I would look up at the clock, I'm like, to me it's like, hurry up and, you know, finish right. I just want to end his game. [END CLIP]

JULIO RICARDO VARELA Suddenly, it looked like the U.S. could turn the tide in the final minutes, but then. Right here, baby! Right here Carlos! Carlitos!

[CLIP]

SPORTS ANNOUNCER Fight for the rebound here comes Arroyo.

JULIO RICARDO VARELA Carlito!

[CLIP]

SPORTS ANNOUNCER Arroyo draws the foul and 1. [END CLIP]

JULIO RICARDO VARELA That was awesome! Up by 11.

Puerto Rico answers the charge. Suddenly, only one-minute remains. Puerto Rico is back to leading by 20, and it's clear the U.S. is run out of time to catch up. With victory near, the coach takes Carlos Arroyo out of the game.

[CLIP]

SPORTS ANNOUNCER Carlos Arroyo, the game of his life. 24 points as he comes out. [END CLIP]

JULIO RICARDO VARELA As he walks off the court, cocky as all hell, he looks at the stands and grabs his jersey and pulls forward the part where it says Puerto Rico, as if to show everybody watching the name of the place he's from. Oh, that was awesome when he did that. In part, it was a gesture of defiance to a U.S. player who had fouled him a few moments ago, but to many in the audience, watching, the message was way bigger than that.

FLOR MELENDEZ Fue como decirle a los tipos

JULIO RICARDO VARELA Flor says, that it was like Carlos was telling the Americans

FLOR MELENDEZ nosotros somos los poderosos, vité, o sea

JULIO RICARDO VARELA Look, we're the powerful ones. In the newsroom, in San Juan, people started hugging each other, tears were falling. The final score, 92 to 73.

[CLIP]

SPORTS ANNOUNCER It's finally happened, the United States loses an Olympic play with NBA players. They showed some signs in the second... [END CLIP]

JULIO RICARDO VARELA Back at the offices of El Nuevo Dia, everyone was buzzing to get the paper ready for the morning. They had already decided on the cover when Hiram saw a photo come in that instantly caught his eye. It's of Carlos Arroyo showing off his Puerto Rico jersey. It was this quick moment on the court. If you blinked, you could have missed it. And Hiram says.

[CLIP]

HIRAM Esta es la foto! [END CLIP]

JULIO RICARDO VARELA This is the photo. The layout designer was like, no way. We already have the cover. But Hiram's like this – is the photo! This is the photo we're going to be talking about 50, 100 years from now. This needs to be the cover.

[CLIP]

HIRAM Cuando hablemos de ese juego. Esta es la foto que siempre va a tener la gente en la mente [END CLIP]

JULIO RICARDO VARELA All night long, the island celebrates the win. The next morning, the team wakes up and heads mostly together to the cafeteria for breakfast. And as they walk through the Olympic village,

FLOR MELENDEZ Eran todas las delagaciones.

JULIO RICARDO VARELA All the delegations of athletes from around the world were there. And as they walked into the cafeteria, Flor says you'd think it was a Puerto Rican party.

FLOR MELENDEZ Todo, todo, todo lo países

JULIO RICARDO VARELA Everybody from the Germans, the Iraqis, all of them, stood up, stopped eating and clapped for Puerto Rico.

FLOR MELENDEZ Imaginate, eso uno no se lo imagina nunca que eso puedo pasar

JULIO RICARDO VARELA He says it's something one never imagined could happen. They were getting a standing ovation, from the world. And it's just a fleeting moment, that's the thing that is just so bittersweet about it, it's 24 hours of joy and then that's it. The team doesn't perform nearly as well for the rest of the tournament. They were eliminated in the quarterfinals in a game against Italy. But when Puerto Ricans remember Athens, they don't remember losing to Italy, they remember beating the United States. Rolando Houritiner says people on the island still come up to him and thank him.

[CLIP]

HOURITINER It was very emotional for the island. It's the day that we beat USA, it's like David beat Goliath. [END CLIP]

JULIO RICARDO VARELA It hasn't been 50 or 100 years yet, but the image of Carlos Arroyo grabbing the jersey has become an enduring symbol of Puerto Rican power and pride. Everybody knows that image was even painted as a mural in Viejo San Juan. I think it means more than ever now. To me, 2004 was before the hard times hit Puerto Rico. The debt, hurricanes, people leaving, political failures, this creeping feeling of failure, of no hope, because everywhere around you, you know you're not winning. So I think there's something special about looking back at what happened in Athens. That moment when the game is over and Puerto Rico is on top, it tells people that, yes, you can win. So that's why you've got to hold up that jersey and show it off a little bit.

BOB GARFIELD That's it for this week's show, but you can and should go to the La Brega podcast feed to listen to the other episodes in the series. Every episode is available in English and Spanish.

BROOKE GLADSTONE The stories in this episode of On the Media were produced by Alana Casanova-Burgess, who's actually leaving the OTM team this week to go on to new adventures. She's been a prime mover of some of our best work, a passionate voice, and a leader. Alana, you are a force who helped propel us forward, and we will eagerly, instantly tune in to whatever you do next. Katya Rogers is our executive producer. On the Media is a production of WNYC Studios. I'm Brooke Gladstone

BOB GARFIELD and I’m Bob Garfield.

ALANA CASANOVA-BURGESS Leadership support for Labriola is provided by the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, with additional support provided by Amy Liss.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.