[music]

Melissa Harris-Perry: I'm Melissa Harris-Perry, and you're listening to The Takeaway. Here at The Takeaway, we love our music, classic tracks, and new hits, but these days there are fewer new hits on the top charts. According to music analytics firm MRC data, new music makes up only 30% of the current music market while artists from previous decades are among the most downloaded on iTunes, and on Spotify songs like Dreams by Fleetwood Mac are being discovered by new audiences. Thanks in part to platforms like TikTok.

[music]

What's going on and what does this signal about the future of the music industry? Ted Gioia recently wrote about the trend of old music dominating the music market. He writes the music and popular-culture newsletter, The Honest Broker on Substack. He's also the author of 11 books, including most recently Music: A Subversive History. I asked Ted exactly what we mean by old music.

Ted Gioia: The data measures old music as anything more than 18 months old. With the huge increase in the consumption of old music, many people take comfort in that. They say, "Well, Ted, this is only music from 2020," but in fact, if you dig more deeply into the data, you see that the most popular songs right now aren't songs from 2020, they're songs from 30, 40, 50 years ago. I see that wherever I go. I go to a retail store or a restaurant it's always songs from the '60s or '70s, and the indications from the industry is the same. The hottest investment right now in the music business is buying the rights to songs from musicians in their 70s or their 80s.

Melissa: As an X-gener about to head into my 50s, I'm not surprised that my music is more popular. This is exactly what old people do. I mean old people as in we are older than 18 months ago. Isn't this like the standard thing where we make fun of whatever generation follows us, that millennial music is not as good as ours Z Gen music, is not as good as ours?

It's the same sort of thing my parents would've said to me. Then maybe this is about baby boomers who have driven the economy since the moment of their birth. Is this just like a generational thing that as the boomers fade out new music will emerge behind it, or is there something different going on here?

Ted Gioia: I hear many people tell me exactly what you've said. The reason that the new songs are more popular than the old songs according to many people I talk to is that, well, the old songs are just better. I have some sympathy with that. If you judge songs by their hits on the radio, they're not an especially illustrious group. I will say, however, that there are many great musicians out there doing outstanding work today, they're just all under the radar screens.

The real damaging thing to the culture right now is even young people seem to be listening to the old songs. I was out at a retail store the other day, the clerk was half my age and he's singing along to Sting and The Police and Message In a Bottle while he's checking me out. That's a song from 1979. Then I go to a restaurant just a few hours later, everybody in that restaurant is 30 and under in the workgroup, but the songs are all more than 40 years old.

I actually asked my server, I said, "Why are you playing all these old songs?" She looked at me in surprise, and she said, "I like this old music." I think this is increasingly happening. The younger people are also listening to the old songs. That can't be good for the future of our musical culture.

Melissa: Let's make it concrete, who are some of the artists that we're seeing on the chart that are what you would define as old music?

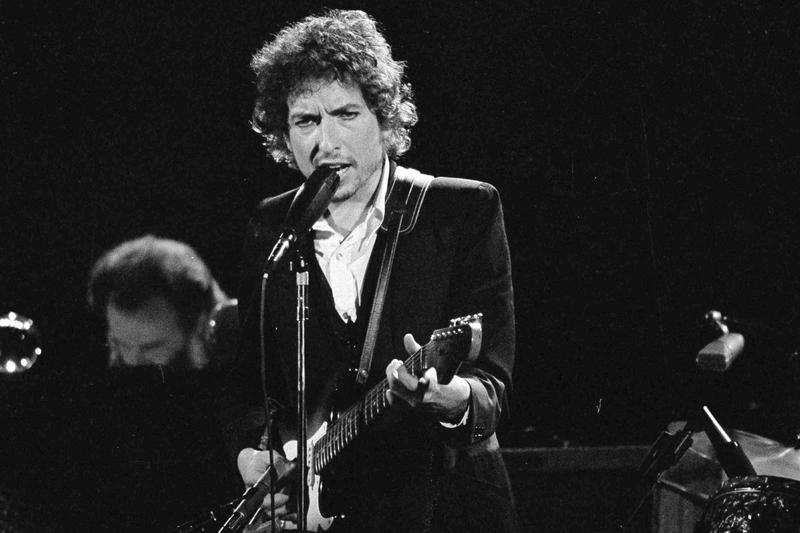

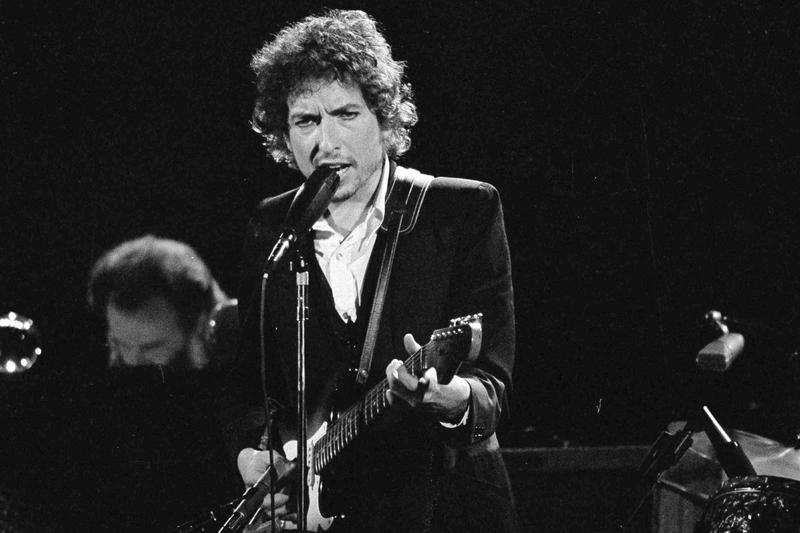

Ted Gioia: I think the best indicator is following the money. If you look last year, a total of $5 billion was invested in purchasing the rights to old songs. This is extraordinary. If you go back a few years ago, the industry was spending a fraction of that on publishing rights. Now they're investing in old songs rather than new artists and the musicians they targeted, the ones they spent the most on were Bob Dylan, Paul Simon, Bruce Springsteen, and in some instances, musicians are dead, like James Brown or Ray Charles, but the bottom line is music from the 1960s, the 1970s, that seems to be the hot ticket and investment right now. If you follow that out, that can't be very encouraging. These are musicians that aren't going to be around for much longer.

Melissa: Tell me why we should care. Why is it scary that there isn't the new music being made? A market is presumably kind of value-neutral in that sense, so if the market is out there and the preference is to consume something that is older, why be afraid of that?

Ted Gioia: From the point of view of the music industry now, they make just as much money when somebody streams an old song as a new song. That wasn't true 30, 40 years ago. If you were selling records, you needed to sell something new every day, so newness was a factor, but now the economics don't favor new music. How does that impact our culture? The way I like to describe it is in the future every month is going to be like December.

What do I mean by that? In December, we're used to hearing those same holiday songs every year and they don't change. The holiday songs you and I hear now are pretty much the same ones we heard as children. We accept that fact, in December you're just going to hear old music over and over again. My fear is it's going to be like that now in January and February and March and April, and we're just going to hear the same old songs again and again.

When that happens, an art form petrifies. This happens to art forms. For example, opera, the 10 most widely performed operas haven't changed much in a century. There's some art forms that just go into this fossilized form, and that's not a healthy indicator of their future. I fear at an extreme that popular music is going to be coming more like classical music in which there's not much change from year to year. I don't think that's a good sign for people who want music that's relevant to what we are, who we are now, and what we're doing.

Melissa: You said the word 'streaming' and obviously the questions about Spotify and the critiques of the ways that streaming has altered-- you're talking about profit, but I mean altered the way that artists can profit it all from what they're creating. How much of what we're seeing here is in fact driven not by a neutral market, but by the realities of the technology of streaming?

Ted Gioia: I'm a big fan of the digital world, and it does bring some advantages to a musician. As a musician now I can put a song up on the web this afternoon, and theoretically it can be heard all over the world tomorrow, and I have direct contact with my audience, but that's theoretically. In practice, streaming has been terrible for musicians in most instances. The money they make is less, the opportunities they have to gain fame and fortune have fallen significantly. This makes it very difficult for creative people.

Here's probably the most interesting way of looking at it. Every year Forbes publishes a list of the highest-earning musicians in the world. If you go down the list now, much to my amazement, I found everybody on that list makes more money from their non-music deals. They've licensed their brand to do an athletic shoe, or a cosmetic sign, or a brand of booze.

What a sad commentary that even the most successful musicians now have to do side deals in order to rise to the top of their profession. These aren't positive signs. I really don't think so. Not by any measure.

Melissa: Ted Gioia writes the music and popular-culture newsletter, The Honest Broker on Substack. He's also the author of Music: A Subversive History. Ted, thanks for joining us.

Ted Gioia: Thank you for having me.

[music]

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.