BROOKE: There’s a saying from the early days of newspapers that goes: Everyone gets to be in the paper twice: when they’re born, and when they die. The second part - the obituary - is, many think, a dying beat. Specifically the obituary of people who otherwise wouldn’t make the news.. Jim Sheeler, a former reporter for the now-defunct Rocky Mountain News in Denver won a Pulitzer for his piece about a Marine major who helps families of soldiers killed in Iraq cope with their loss. But before that, Sheeler was an obit writer. Jim, welcome to the show...

SHEELER: Thanks so much for inviting me.

BROOKE: You say that obituaries written about everyday people are on the decline. Why is that?

SHEELER: Part of it is just the decline in space in the newspapers. And also that newspapers have seen obituaries as cash cows. The vast majority of obituaries pages these days are paid family obits. And they're quite expensive.

BROOKE: Seems to be one kind of classified ads that Craigslist can't raid.

SHEELER: Exactly. Newspapers also charge to keep the obituary online. So you have to keep paying every year to have the guestbook to continue. For families that can't afford obituaries, the kind that I wrote about mostly. Those names might not show up in the paper at all.

BROOKE: And it seems like many regular people are either consciously or unconsciously writing their own obituaries through their social media. What can an obituary writer do that people aren't doing for themselves.

SHEELER: There are some really fantastic self-written obituaries and family-written obituaries. But to get a sense of who that person was by looking through their scrapbooks and family stories and distilling that down into a real story that's not just interesting for the other family members but to tell the readers why this life was important. One thing I always ask the family members is what did you learn from this person's life. What can I learn from this life. What can I take away from it. And add to my own. How can I make myself better. One of the things I've said that if journalism is a subsidized education obituary writing is the philosophy beat. It's where we learn about life and death and what makes up all of us.

BROOKE: But isn't it true that in many newspapers the obit beat was regarded as the beat of last resort for fading journalists.

SHEELER: It many ways it was. It was often referred to as 'the Siberia of the newsroom.' I saw journalists at my own newspaper punished, 'obits for you for the next 6 months.' But when I started writing them I actually realized what a joy they can be to write. One of the first obituaries that came across my desk from the funeral home that was in the days when they would just give you a little bit of information about the person and it said. "She was a florist and a butcher." I would have loved to have written this story as a profile. And a realized, well actually I still can. That's the great thing about these obituaries. They're the last chance to tell this person's story. There's a lot of pressure in that. But there's also a lot of reward. I would receive hugs after interviewing the families. Because they were so thankful. It was really cathartic for them. We're so scared about talking about death that a lot of people don't know what to say. And so they don't say anything at all. I was sitting with a man who had lost his wife to breast cancer. She was 44 years old. I had asked him that question about what did you learn from her. And he recounted this story of how not long after she had been diagnosed she was reading the newspaper and there was some inane story on the front page about politicians squabbling about some stupid issue. This was right after she'd been diagnosed so she throws down the newspaper and she points at it. And she says, 'You know, these people need cancer. Not enough to kill them. But just enough to make them realize what's important in life.' And then he looked at me and said, 'You know Jim, it's not that there's too much cancer in the world, it's just that it's poorly distributed.' Absolute genius. It's not something you'd find by just calling someone on the telephone. And that's something else about these obituaries: they take time. I did almost all my interviews in person. In today's newspapers where you're having to write several stories and life tweet and multi-task so many ways. There isn't always time to sit back and listen to the stories that mean that most. The stories that last.

BROOKE: Your Pulitzer Prize winning piece, "Final Salute," about the Marine that helped families cope with the loss of loved ones in Iraq. Do you think you could have done that without all those years on the obit beat?

SHEELER: Absolutely not. I learned so much about talking to families. Being there. Knowing when to shut up. And when to let them grieve. And when to listen. And how to listen.

BROOKE: What do you mean 'how to listen.'

SHEELER: People leave behind stories. And these stories will tell the obituary for you sometimes. One of the primary people in the story is Catherine Cathy who is a 23-year-old pregnant war widow who I met just a couple days after her husband was killed. When we were talking she mentioned that she had taken up knitting when Jim was away at Marine training core. I asked to see some of the things she had knitted and she took out this baby blanket and she told me its story. Which was that, um, the night before Jim left for Iraq he knew that he wouldn't be back in time to see the baby born. So he slept with that baby blanket because he said that when the child was born he wanted the baby to know how his father smelled. And that was the lede of my story the next day. 'The soft blue-green baby blanket still smells like 2nd lieutenant James J. Cathy.' That's so different than the standard news story. Writing obituaries taught me how to look for those stories in places like a baby blanket.

BROOKE: One more example of precisely that: You took the shortest obit in the paper and you reported it out. Johnny Richardson.

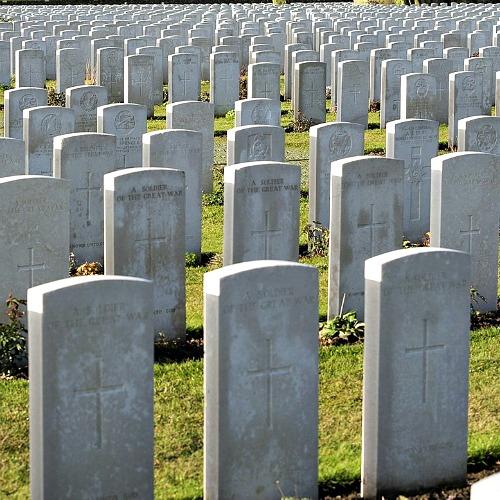

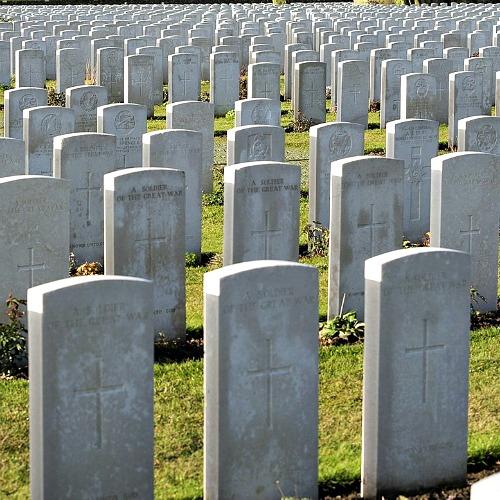

SHEELER: Just said basically that Johnny Richardson had died. He enjoyed listening to jazz. There are no survivors. When you have no survivors, they basically take things that might mean something, they put them in a box in the public administrator's office. And so I went down to the public administrator's office. And I found that all of his belongings basically fit in a box the size of a shoe box. And I started reporting from letters and things he'd left behind. He had shined shoes at Denver International Airport for decades. For the people who knew him, whether it was the people he shined shoes for athlete airport. Or in the salons downtown. He was this really special, quiet by thoughtful guy. He did leave an impact in the salon where he ended up working downtown. They left a memorial on his shoe-shine seat. And here he was about to go completely unrecognized. And without a grave marker at all.

BROOKE: So he had an impact. Did your work have an impact?

SHEELER: Yeah. After his story ran, they raised enough money to actually buy him a headstone. And when I got to Denver a lot of times I'll say 'hi' to Johnny in the cemetery.

BROOKE: Most of us are not famous. Most of us just pass through. And that's the coverage that is disappearing with the obituary of the regular person. Since we're such a narrative driven form these days, why can't we keep this going?

SHEELER: There are still reporters who are out there doing this. Andy Meachem at the Tampa Bay Times is one of the best obituary writers writing today. And he does many of these. He calls them epilogue. The problem is that it does take so much time to sit with these families and listen for the stories. They don't always come out in the very beginning. You have to jump through a lot of cliche. People say, 'he would have given the shirt off his back to help somebody.' and I always would challenge them, 'well did you ever see him give the shirt off his back to help somebody?'

BROOKE: Laughs

SHEELER: Well at one point someone said, 'Well I did see her...one time we were walking a long and she took off her shoes and gave them to a homeless person.' That's the beauty of these obituaries. That's the beauty of these obituaries. They're not these cliches. Or the eulogies. They're the stories. We're all made up of stories. And trying to find those last stories is one of the most important jobs in the newspaper. I think that because of the time in takes and the money it makes to not do them, that's one reason they're fading away.

BROOKE: So Jim, we're going to do an obit about someone who hasn't had one written about him or her. You have any pointers?

SHEELER: I would just call up and say, I just read this small little thing that funeral home sent out about your loved one and I know there's a much bigger story there. Would you have time for me to come and look through some scrap books and tell some stories. And almost inevitably they would say 'yes.' A few would say 'no' and I never pressed it because I made it clear that I was going to tell the whole story. I did stories about people who were jerks. And whose family members admitted it. But that made them who they were. And it made those stories really wonderful. You notice things when you're scanning the obituary pages everyday. The husband that dies hours or days after his wife. Amazing love stories.

BROOKE: Well that sends us on our way. Jim, thank you so much.

SHEELER: Oh thank you so much.

BROOKE: Jim Scheeler is a Pulitzer Prize winning journalist and now a journalism professor at Case Western University in Cleveland.

SHEELER: Good luck with the obit.