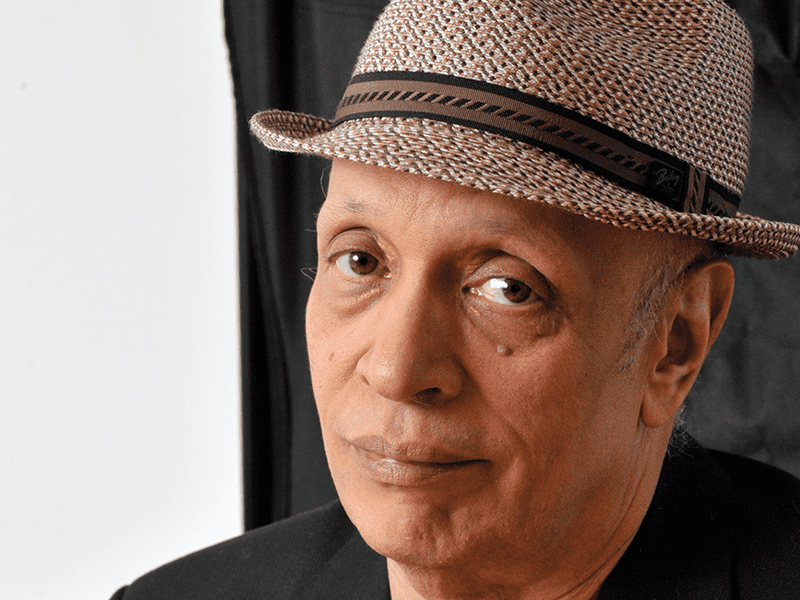

Novelist Walter Mosley on Family and Forging His Own Path

( Marcia Wilson )

Walter Mosley: People say, are you a successful writer? And I'll go, well, you know, I'm a critical success, but I'm not a popular success and I'm not, it doesn't matter to me. I don't want to change places with some popular writers because then I'd have to write the books they write. And I don't like those books.

Helga: I'm Helga Davis and welcome to my show of fearless conversations that reveal the extraordinary in all of us. My guest today is the acclaimed author Walter Mosley. Walter's work comments on the intricacies of Black livelihood by grounding science fiction and mystery in America's turbulent social and racial climate.

Decorated with the O. Henry Award, the Anisfield Wolf Book Award, a Grammy, and more. and PEN America's Lifetime Achievement Award, Walter is a testament to Black artistry. He joins me in the studio following the release of his latest novel, Farewell Amethystine, to discuss the types of overlooked characters and stories he wanted to celebrate in his novels.

Glad to see you brought your water with you. Yeah? Okay. And let me know that that chair is okay. Is it too low?

Walter Mosley: No, I don't think.

Helga: All right. I mean, it doesn't bother me. So, you live in New York? I do. I live in Harlem. And you were born in Harlem. I was born in Harlem Hospital. I just found some photographs. My brother took them when he came back from Vietnam.

And there is a destroyed Harlem. This is in the 70s. I think he came back in 1969 or 1970. And you see all the shells of the buildings, the rubble in the street, the folks out on the corners, high. There was a lot of that, and he said there was a lot of that also in Vietnam, and then they sent these men home to ashes, essentially.

Walter Mosley: That was back when heroin was a crime, rather than a disease.

Helga: Right. Yeah.

Walter Mosley: Yeah, and have you always been there

Helga: then? I did go and live somewhere else. I lived in Massachusetts for school.

Walter Mosley: Where?

Helga: At Williams, so I was in Williamstown. Uh huh. And then I moved to Italy for a little bit. I followed a man to Milan.

To Milan.

Walter Mosley: Milan, so in the north.

Yeah, it's

Helga: not an easy place to be because there's a lot of industry there. A lot of the folks came from Naples and worked in industry and then they forgot they were from Naples and became sophisticated city people.

Walter Mosley: Yeah, the culture there is like clothes design and stuff, right?

Helga: Yeah, there's a lot of that. And there's also a lot of agriculture there. So you have your olive oil. There's cheese, there's pasta.

Walter Mosley: So then you left.

And then I left there because you can't run from home forever.

Well, some people can.

Helga: Some people can. I couldn't.

Walter Mosley: Yeah.

Helga: And so I came back. Didn't have any expectations about what it would be like to be here again, heartbroken, without a place to live, necessarily.

Walter Mosley: What year is that? Ooh, what year was that? I have no idea.

Oh, come on. You know what year you came back from Milan.

Helga: No, I actually don't. Uh,

Walter Mosley: okay.

Helga: Six, seven, five? No idea. I just came back, because that's what I could do. I came back.

Walter Mosley: Yeah.

Helga: And when did you come to New York?

Walter Mosley: Born and raised in

Los Angeles. Lived there until I was about 18.

Went up north. That was 1970, so it was hippies and communes. And then I came back down for a while and just sat in a room for about nine months. And then I went to Goddard College in Vermont.

Helga: What were you doing in that room for nine months?

Walter Mosley: I was scribbling little drawings, and I can't draw, though I have never stopped drawing.

And I've gotten better, but I still can't draw. And then I went to daughter college, but I dropped out, mostly because of my father. Because my parents had money, but he wanted me to pay for it, but he was also afraid that I was going to have accidents, so he wouldn't let me learn how to drive. He wouldn't give the permission to take drivers ed.

So I couldn't drive. And it's in Vermont, it's 20 below zero. Yeah. But you need to get a job. I said, yeah. It's minimum wage. I can't drive, it's 20 below zero. And so I dropped out, which made him very mad at me. But I stayed in Vermont, and I went to State College, which cost nothing. And then I moved down to Massachusetts in Amherst, I went to UMass Amherst, and then I lived in Boston for a while.

And then I moved to New York. It was about 1980, and then I kind of spent my time between New York and L. A. right now, but New York's the place.

Helga: When you dropped out of school, what did you think you were going to do?

Walter Mosley: I wasn't thinking.

I mean, you know, it was the 70s. You could do anything. So it didn't matter.

You know, something will come, and I will do it. I liked what I studied. I've never had that thing. I think I always blame it on California. People in California are different.

Helga: In that?

Walter Mosley: A woman who's retiring. Retiring at 70. Anywhere else in the country, if you ask that woman what she's doing, she'd say, I want to see my grandchildren, I'm going to travel a little bit, the husband, he's kind of lost in himself, so I'll maintain him and his life.

But in California, it's like, well, you know, I've always been very limber. And I can touch my toes, and so I think I'll make a ballet company of elderly women. And you laugh. And then the next year, they're performing for the President of the United States, the 70 year old ballet.

Helga: When the men do.

Walter Mosley: Hmm?

Helga: So we have your assessment of what the women did, which was essentially to take care of the

men.

Walter Mosley: You see, that's why I'm saying that. Men, they have the same kind of thing, but it's much earlier in life, in your forties and into your fifties. But then you kind of get lost, most guys, then. So I don't think about them as an example, because you're in your thirties and you're forties. But people still imagine, oh, I could do anything.

I can start a commune out in the woods, I can start to sell brown rice to people, I can, I'll make my own life. And I feel like I got that from California, so when I was anywhere else, I didn't, because you asked me that question, it comes right to me. I didn't care. I was, I stopped doing that because I was finished with that.

And it didn't come back to me until I graduated from my college in Vermont, and my father refused to come. He said, I paid for your college, and you just, you threw it in my face and dropped out. He said, I'm not coming to your graduation. I

said, all right.

Helga: And you felt what about that?

Walter Mosley: Well, I've always had some distance from him.

Yeah, I love my dad very much. I mean, he's a major thing in my life. And I just put up with his craziness. His mother died when he was seven. His father, who did logging, Went to do logging and never came back, probably died doing it, a lot of people did, in Louisiana. And my father's been on his own since the age of eight, and when he was eight years old, he jumped a boxcar to go to Houston, to walk around Fifth Ward, Houston, Texas, to find a job.

His maternal grandfather, so he had a lot of trouble, and I accepted it, because I was doing what I wanted to do.

Helga: Did you avoid Vietnam and?

Walter Mosley: Oh yeah. Yeah. When Muhammad Ali died, somebody asked me to write about it, and I said, I was telling everybody that I'm not going to go to Vietnam because I don't have anything against the Vietnamese people.

So, I didn't realize at the time that I was. It's just so wonderful, you know, that somebody has this power over you without the kind of messianic stuff going on. It's just, they say something, it's true, you accept it, and you continue. You go on.

Helga: They didn't come looking for you, knocking on the door?

Walter Mosley: Oh no, by the time The year that they would have done that, I had a high number, but they were only drafting people between the first of the year to about the 30 something.

They just picked numbers out of a thing, and I was like 234, so I was never going to get drafted. I mean, it was over.

And you had friends who were drafted and came back? Actually, I had friends who went,

and I had friends who didn't go, but I'm not sure if I knew anyone who was actually drafted. Yeah. I don't know.

A lot of people, you know, went to school and wanted to go, and a lot of people got scared and went, and a lot of people got college, uh, deferment. Right, yeah. There was a lot of different things.

Helga: I was thinking about when you grew up. You were born in 1952?

Walter Mosley: Yes.

Helga: So, when you were very young, there was Brown vs. Board of Education, there were the Freedom Rides, the passing of the Civil Rights Act, Loving vs. Virginia. Mm hmm. And the writers around that time, also James Baldwin, Langston Hughes, obviously there are many more. Ralph Ellison.

Walter Mosley: Richard Wright.

Helga: Richard Wright, Alice Childress, Pauli Marshall, and Octavia Butler, who was born in 1947.

I think about you in the context of these people, this time in this country, and I'm wondering what influence that time may have had on you as a writer and Just as a person, or as a hippie in California.

Walter Mosley: Well, you know, I knew some of those people. I certainly knew Octavia and Polly Marshall and some others.

I mean, later, because I didn't even think about being a writer until I was like 34, 35. I was influenced by Writers High, everybody who reads. But who impacted me was my family. I had all of these black Texans in Southern California who were my family. Then was my mother, of course, and the Jewish clan. They were very similar at that time.

Everybody came from poverty and oppression and racism. And so I cared about them. When you think of somebody having an impact, my father had this friend named Hollister P. Fontenot. And Hollister, like my father, owned an apartment building that he rented apartments in. And there's this one guy, it was a black guy, and he was a policeman.

And he wouldn't pay the rent. He just said, I'm not paying you no rent. I'm just not paying, whatever reason. And so I remember Hollister coming over to my father's house one day, and he's talking to me. And he said, yeah, you know, he said he's not paying his rent. So I went over there, and I sat down in his kitchen.

He sat down across from me. And I took out my 41 caliber, and I put it on the table. And I said, now it's like this. There's three things. Either you're going to get killed, I'm going to get killed, or you're going to move out. That's the three ways, you know, and he moved out. Because, you know, there was no winning that, that for him.

But that was my family. The stories, and the same stories from my mother's side of the family. Poor people and how they dealt with everything around them and everything between them. And that's why I became a writer, because I wanted to tell stories with those kinds of people. They were black people, certainly, but it wasn't overly politicized.

I was talking to Paul Coates, actually, this morning, and I was trying to say, I'm trying to write this romance right now. Everybody's black, and we know the blackness and the life and some of the troubles, but what I want to do is celebrate the lives of these people. I mean, all kinds of different ways. And of course, I wanted to write about black male heroes because even though I like a lot of the people, Baldwin and Richard Wright and Ellison and there's a whole bunch of people where you have black male protagonists, but they're not black male heroes.

There are people who, they've been so mutated by race and racism and their response that they hate their neighbors, they hate themselves, and they also hate themselves. The country that made them this way. And that's all good and well, and it's true a lot for a lot of people. But then you have people like Hollister P.

Fontenot, and my father, and a lot of other people that say, we're just going on, uh huh, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, that happened, you know, and said, but I'd rather be living my life than their life. And me, too. I was saying, God, this life is great. I love my family and the way that they maintain.

Helga: So you didn't feel a need to write those stories again because they were already doing that and you wanted to say something different.

Walter Mosley: I mean I loved Long Dream by Richard Wright. There's a lot of things you could get from that book. But I got all the way to the end and at the very end this guy, you say, oh my god, he's gonna get killed, something terrible's gonna happen. But instead of, you know, Anything that might happen, he bought a ticket and flew to France.

And I was just like, that is the moment that struck me in that book. I went, wow. And I was 16. I went to France that year. Because I said, I need to go. I need to go to France where it was wonderful.

Helga: What was so wonderful about being there?

Walter Mosley: For me, it was almost like a non sequitur, right? In Wright's book, A Long Dream, it was a non sequitur.

And for me, it would be like saying, well, rather than, I have to do all these things which people expect of black people, I have a friend, he's a wonderful guy, his name's Mark Nieman. And Mark and I were in high school together. Now, you know, Mark's family is a very Jewish family, you know, and they go to shul and they do all these things.

And I was there one day at the house, and I guess his mother didn't know that my mother was Jewish because, you know, I didn't run around saying anything about my family because that was just me. And when she heard it, though, she says, You're Jewish? I said, Yeah, my mother's Jewish, Ren. I could marry your daughter.

And she went. No, you could never marry my daughter. It was so funny, you know, how racism gets into all these places, you know, but I could go to France and everything would be different. And it was. I came back and everything was still different in my head.

Helga: I remember when I came back from Italy, one of the things I felt was the violence of New York.

Walter Mosley: Like everything felt different. violent to me. My eyes were always full of advertisements, and I felt like I couldn't get away from noise, and I wanted some silence somewhere in my head to be able to think, to be able to see the things around me. When you came back to the States, how were you different, or were you different?

I was completely different. You remind me of a story about my mother, though. My mother was raised in New York. She went to Hunter High School and Hunter College. I think she graduated Hunter College at 19. My mom was something. But she decided to move to California, so she got on a train and went to California.

She stayed at my cousin Lily's house, up toward Melrose. Back then it was very calm back there. And the next morning my mother got up, and Lily was there, and she was making her breakfast. And she says, well, how are you? She goes, oh my god, I couldn't sleep all night. She goes, well, what's wrong? I said, it's so noisy.

Oh, oh. And she went, noisy? She goes, yeah. As soon as the sun came up, all these birds in the trees behind your house that were making so much noise. She didn't mind sirens and, you know, you know, it's just that funny thing, which is, what is noise?

You know what, and like you were saying that it might have been, silence is also a kind of a noise.

When it's so quiet, you can hear the pulse in your ear.

Helga: In your ears, and the hiss.

Walter Mosley: Yeah.

Helga: Was it a thing that your mom married your dad? Your mom is Jewish, your father's Black. How did the families receive one another?

Walter Mosley: The most interesting thing about that was, my mother was a Trotskyite. So she was very committed to the worldwide revolution.

And her parents weren't like that, though. My grandfather was a doctor, my grandmother was a person who sent him to medical school by working, doing seamstress work. My grandfather, when she told him that she was going to marry him, he said, and this is how my mother quoted him, she goes, Oh, but, but Elkie, the black people, they're closer to the monkeys.

My mother said, that's awful, and I'm marrying him anyway. And they got married. Now, I was born, these are my grandparents, so they had to come out and see me. But in the, between the times that he came, my father had built a house in the backyard. It had just been a loose structure and he made a house. He walled it, he wired it, he plumbed it, he put the floor in, which is like one of the hardest things in the world.

And my grandfather was walking around the house, you know, he hadn't rented it yet, and everything changed. He basically, much different than American racism, he says, oh. You're not close to the monkeys at all. You're like me, only you're better because I can't build a house. So it was a really interesting thing.

My grandfather actually believed what he was saying to my mother. It wasn't a racist thing, like, oh, you monkeys. It was like, but isn't that what it is? And then he realized, no, it's not true. It was really amazing. You know, and my parents, to explain how they were, if you're on a ship and it's rough waters, you have to start to go with what the waters do.

You fighting against it is not going to help you. If you were willing to change, they were willing to accept you, which was a really amazing thing on my father's part. But his life had been so hard. I mean, his life had been so hard, and most of it had been lived among black people, and it was tough. My father went to World War II.

With a hundred guys from 5th Ward, Houston, Texas. And he went through the war, and he came back, and there was about 89 of those guys left. Right? You know, a couple of them got killed with bullets, but they died from different things. But almost everybody he knew in 5th Ward. Because life was much more dangerous in Fifth Ward than it was

Helga: On the battlefield

Walter Mosley: in the biggest war in the history of the world.

And so to survive that, you have to be flexible. That's why he left Texas. That's why he came to California. He said, Wow, because he could see it. Most people couldn't see it because they're living in it. He went away, and he came back, and oh, wow, okay.

Helga: And the same thing with you, I imagine.

Walter Mosley: Yeah, I came back, and I was different.

The world I was in was the same, but when you're different, you see different things, right? I mean, it's kind of amazing.

Helga: What were the things that felt very different to you?

Walter Mosley: It's a very hard thing to explain. A lot of it had to do With the intellect. Because I went to Hamilton High School in Los Angeles, and in the junior high school, Louis Pasteur Junior High School, in the high school, you could walk down the halls, you look at one class, and they're all white students in there, you look at another class, they're all black students in there.

It went like that. We were segregated. And there was like one or two really, really smart black people, but they were the only ones in the smart classes. And I just decided, I said, well, you know, I belong over there. Because here you have to remember questions like true, false, what year, this and that. And the other one that you have to write essays.

And I said, I'm good at writing essays. I'm not good at remembering what year they discovered America as if that's going to make any difference. And so I went there. And I remember once I. I got really, really angry at my counselor, and I got so angry that I realized later that she got scared, and so she just put me in the class I wanted to be in.

Helga: So you got angry, and what happened?

Walter Mosley: I was just talking. I mean, I didn't, certainly didn't, Pick up anything or grab her or anything, but I was mad. And I said, listen, you told my friend Michael Belkin, you told him he could be in any class he wants, and you're telling me I'm a substandard. And I was yelling about it.

And she just said, okay, fine, I'll put you in the class. You want to go in Mr. Chagard's English class? I said, yes. Okay. And from then on, I was an A student, and everything was great. But I didn't think about any of it. It just happened. I walked in the room, she said what she said, and I responded. It was fun, you know?

Ever since that, when I got back from France, it was fun. By the by, my father had said for many years after that, that the worst thing he ever did was to send me to France that summer. He said, it's the worst thing I've ever done. Because, you know, I became a hippie. I would argue with him. I'd say, no, I'm not doing that.

No, no, I'm not thinking like that. No, I'm not interested in that. Yeah, you do it, but I don't do it. And I never insulted him, but I certainly insulted the life that he wanted for me.

Helga: And so when you left school, did that just kind of pile on to his evidence that you were failing at life somehow?

Walter Mosley: Oh, yeah, absolutely.

My father once told me, he said, you don't know. You don't know how to take care of yourself. You don't know anything.

Helga: What do you think that meant to him?

Walter Mosley: That I couldn't live the way he lived. Because he learned how to make it. And he did very well. There's no question about that. And because I wasn't thinking like that, and because I wasn't worried, because I answered his questions much the same way that I'm answering yours.

In his will, he said, He said, I wrote a will, and I'm going to take everything that I own, I was an only child, and you're going to get little slices of it each year, little, just a little bit, like a 5 percent or 6 percent, every year, because I know if I gave it all to you, you'd just waste it and throw it away, and it wouldn't be worth anything.

And I didn't really believe him, but after my father died, I got his will, and it's exactly what it said. I had outlived that term, but it was just, it was wild. He was wild. He needed to control me, and so therefore he needed to lessen me. And he couldn't help it, but I really, I love my father so much, I thought he was so great.

I learned so much from him. But he was very limited by being an orphan so young in his life. Being a poor black orphan in the deep south in the 1920s. I once asked him, I said, Dad, all my friends parents talk about the Depression, how come you don't talk about it? And he said, Walter, we didn't even know there was a Depression until it was over.

It's because it was poverty, and he was very smart, my dad, also my grandfather. Who taught him. Who I'm named after.

Helga: You're listening to Helga. We'll rejoin the conversation in just a moment.

Avery Willis-Hoffman: The Brown Arts Institute at Brown University is a university wide research enterprise and catalyst for the arts at Brown. That creates new work and supports, amplifies, and adds new dimensions to the creative practices of Brown's arts departments, faculty, students, and surrounding communities. Visit arts.

brown. edu to learn more about our upcoming programming and to sign up for our mailing list.

Helga: And now, let's rejoin my conversation with the crime fiction author, Walter Mosley.

So you were always writing?

Walter Mosley: I did write, I mean, for school and stuff, and I liked that stuff. But as far as fiction writing, it wasn't until I was 34. I was a consultant programmer for mobile oil on 42nd over on the east side.

And I was there on a weekend, and so I was alone, and I was Typing computer code, and then I got tired of it, and so I wrote a line. On hot, sticky days in southern Louisiana, the fire ants swarmed. I wrote that line, and I went, wow, that could be a novel. You know, I read that book, The Color Purple. You know, I, I, that's how, she said that stuff, you know.

And so, I just said, well, maybe I could be a writer. But that goes back to the woman in ballet at the age of 70. I said, I can be a writer now. And really, my father hated it. I would talk to him about it. And he'd go, you can't be a writer. This is not writing. You can't do that. And he said, he was so smart, though.

He said to me, then, this was like in the 80s, he said, Water. Forget about this writing stuff. What you should do is you should get a job in the prison system. That's a growing business. And he was right, right, right. Okay, so it's tough. So what? Just wow. Yeah, well, you know, I mean, it's that realness about my life that I love.

And you know, there's a thing that if you and your people are not in literature, You're not in history. Because nobody reads history books. I mean, historians do. You know, and then they decide what they're going to tell you. But, most people, if you see a show, a television show with a black person on it, or if you read a book that reminds you of the way you speak, and the way your parents and your grandparents, I mean, that makes you a part of life.

And other people read it. I mean, other people are saying, wow, that's very interesting. And either they remember it, like Bill Clinton reading my stuff, or they're surprised, wow, that's just the way my people acted. That's interesting.

Helga: And then the stories, you modeled after people you knew and know and things that you heard.

Walter Mosley: A life I know. A life. A life I know. And the characters are all pretty original. But there's a kind of life, a way of living, a history, that I want to get to. I remember one time I just, uh, published a novel and I was reading it, and somewhere in a guy said, Hey, hey, Mosley, you know, you know that house you were talking about down on Hooper?

It's that big blue house, and I said, yeah, uh huh, I remember, and he said, man, I lived in that house.

Helga: Wow.

Walter Mosley: Now, I made up that house, and he lived in that house. Both of those things are true. That, for him, the story, the character, the place, what happened there, was close enough to his experience that he could claim it.

And That kind of is what it's about.

Helga: Did your parents also expect or want you to have a family that looked like your family? Children, house, yard?

Walter Mosley: I don't know.

They certainly never said that to me. It was an odd configuration. I'm an only child. My mother was an only child. My father was an orphan. We were what they say in political theory, monads, who just happened to live in proximity to each other.

None of us came from the classic American family.

Helga: What does it mean for you to be American?

Walter Mosley: Being American is kind of a part of an identity, your nation. I think that in history, people are, were more connected to the nation or their people in a nation. But I'm an American, and that's all good and well, and I live here because I know how it works, basically.

But if another place felt better for me, it hasn't yet, I might be there. It's not a permanence in my mind. It's a place. I'm here. I live here. And, okay.

Helga: Are you writing anything about humans of the 90s and the 2000s?

Walter Mosley: Well, okay. I've written a lot of books, like 60 of them.

Helga: Yes.

Walter Mosley: There's a character I write about, he's Joe.

And Joe is a detective today in New York. And so he's talking about things today in New York. Also Lena and McGill is the same thing. Time and place is so interesting because we all live in really small. And so any one of these characters is going to take you to a whole other new thing. I'm writing a thing right now.

The title is A Romance in Black. And it's about a young man who lives more or less now. But it starts with his mother and his father and it brings him to now. And the book is about love. It's a difficult subject to write about and for it to be relevant. Interesting. It's easier to write about cowboys and Indians.

They're attacking the, you know, the wagons and they're getting in a circle and they're shooting back. But this is an interesting thing. So yes, I am.

Helga: Why is it hard to write about love?

Walter Mosley: Well, because the conflict Unless you get really out there, it's interpersonal. Somebody's in love with somebody, they can be with somebody, they can't be with somebody.

They understand, in the best possible terms, two people understand their differences and how they complement each other. Things like that, which I think are very satisfying to some readers. And, you know, there's someone like, Well, you know, okay, so he met the woman, okay, so they didn't get along, so they did get along.

So you have some kind of mental problem, okay, fine. What's the story? And you go, oh, that's the story. That is the story. That's the story right there. You know. It's really fun. I'm having all kinds of fun doing it. You know, one of the great things about being a black writer in America today, almost no matter what you write about, about someone somewhere in America's history, anything from a doctor to a bricklayer, a bank robber, anything, you've never seen a story with black people doing that.

Every once in a while you'll see it, but you can tell somebody white wrote it because the story is black. Character isn't really a black character. He's just an actor playing a black character.

Helga: And what about you and love off the page?

Walter Mosley: Well, I was not attracted to the relationship my parents had. My father was disturbed, but my mother was really crazy.

And to give you an example, one day when I was maybe 19 or 20, I said to my mother angrily, you never hugged me or kissed me or told me you loved me. And I expected my mother. As usual, to deny. Anything. But she looked at me and she said, I know. She said, my mother was like that with me, and I knew she loved me.

And it was really, it was a shock. I went, oh my god. It's a condition, I don't know what it is, where you can't really express emotion. So I don't think any of us were really My mother was probably the happiest because she had my dad. And that's what she wanted. And then when he died, she had me. That's how her life was.

I feel sorry for her about that, but she was my mom, and she was really good at some things. So I never wanted kids, the idea of being married, all that stuff, I never had it. There was no inner desire. I mean, I got married once, and I said, oh my god, this is such a mistake. What I figured out, I went, my God, this is, this is really bad.

I have to get out of this. Why is it bad? Why was it bad? Well, I just, I was off balance all the time. What does that mean? I would come home and I had to deal with somebody. And we would have arguments about money and all those other things. And I just didn't care. And not only did I not care, I didn't want to be there.

And I have never been in a place where I have wanted that. So, I've never had it. And it's not that I haven't had any relationships and I haven't loved people and really liked people and stuff like that. But it hasn't been like, well, this is what you do. You get married, you buy a house, you have some kids, you know.

I think Octavia was like that. I think Alice Walker is probably like that.

Helga: You think it's the burden, if I can use that word, of what you do, or you think you just

Walter Mosley: No. I just think it's me. I carry myself around with me like a little valise or something, you know, as no, I mean it would be great if I, you know, could say, well my art has made me this.

My art is my art. I'm going to be doing that anyway, and who I am is who I am, because you can be anything. I don't think I had a really good example between my parents. It was not a positive one.

Helga: And who are your friends now? Not necessarily their names, but So you don't have a particular kind of relationship.

So what relationships do you have that feel close and intimate?

Walter Mosley: Well, to begin with, I have three or four friends that I knew In junior high school and high school. So we've known each other more than half a century, which is amazing. And we talk and we get together and, you know, not all the time, not a lot.

But I have that, I think it's like four. And then I have people who I'm very, very close to who, as my life has developed, it's developed alongside with them. Paul Coates is a great example of that. We're very close. I spend a lot of time by myself. I love it. I have this apartment that looks out over the ocean in Santa Monica.

It's at the beach. And if you sit there, you hear the waves crashing. And I'm writing. I'm just sitting there, you know, writing and doing that and talking to people on the phone, various people I know. I had a mentor at Goddard College. He remained my mentor for the rest of his life. He used to say, Walter, the best definition of relationships in life are the people you work with.

Because when you work with people, things have to function. They can't not function. You can't. You can't not carry your load. I hated it when he used to say it, but I think it's very true. That the people that you work with, that you, you know, you carry loads together, moving something from here to there, that actually is one of the best things in your life.

And because, you know, you have Americans, I guess a lot of people in the world are talking about retirement, and you're going, retiring doesn't seem to make sense. I mean, if you retire, like, do chipmunks retire? Do honeybees retire? So they say, well, I'm going to stop being a honeybee, and I'm going to live up on top of this tree, and just eat a little pollen now and then.

I think my work life, I kind of love, and it's like, I have to realize, I'm getting old, I'm 72. And my work life hasn't changed since the day I started writing. I don't know if all this sounds sad or not. No,

Helga: I don't think it sounds sad. It's very clear, and it's a way to be in the world. And it's so important, I think, to hear people talk about other ways of being in the world, so we can get off the treadmill of what love looks like, of what marriage looks like, of what family looks like, of what nation looks like.

Walter Mosley: And some people, I mean, a lot of people like it very much. Somebody will say, well, this couple, they have 14 children. They really must like it somehow, you know? It's like, maybe not. But of course, if you come from a culture where everybody has 14 children, that's a drag if you don't like kids.

Helga: Yeah, there we go.

There are six of us in my family. And I've asked my mom why there are so many of us, because she was pregnant from the time she was 16 until she was in her 30s, and that's exactly what you're saying, that's what you did, you got married, you had children, you had a house, but I had a father who Did not make the same agreement.

And so I wondered why, in light of that, she kept having kids with him. And she said that she had hoped each one of us would have brought them closer together.

Walter Mosley: So they weren't close. I mean, because not making the same commitment and not being closer are two different things, right?

Helga: Yeah.

Walter Mosley: For him, maybe, that kind of made sense, you know, and I think there are a lot of contracts that work out like that.

I said, well, yeah, but what about this? What about that? He said, well, you know, those are just things I had to accept. I mean, both ways. It's very interesting. You get along with your siblings?

Cancel that question. He didn't ask that. Are you taller than most of your siblings? That's what I meant to ask. Are you taller than most of them?

Helga: You know, I wish I knew what getting along was with them because they're so much older. I always think of them like a hand. So my eldest brother is 20 years older and my youngest brother is 12 years.

Wow. And they are one, two, three years apart. And I'm the only American in my family, so they're all born in Nevis and Montserrat. So they are Caribbean kids. And they came here and there was fluoride in the water. I grew up with fluoride in the water, so my teeth held together in a different way. There was different food here.

There were other possibilities here that didn't exist on the island. And it was bigger. It was literally bigger. There was more to look at. There was more to experience. But I grew up in that. This is normal. Right, it's exactly what you were saying before. This was my experience and it was completely normal to me.

And so I think that also separated us in a way because they felt that my life was so much easier. than their life had been. And I don't know that it was necessarily easier, it was very different though. And so the way that that manifested and continues to manifest itself is that there's an otherness. So they're all married, they all have children, they all have houses, they all

Walter Mosley: And do they live here?

Helga: No. I have one brother here, one in Florida, one in Chicago, and two of my brothers are deceased. And I didn't do any of that. I didn't want children, and I definitely wanted to wanted to travel and to see things. Now, my mother said, it's because I went to school with all those white kids. And when I got to high school, I was definitely in a school that did not have many African American students, where my curiosity was encouraged.

And so once you know that thing, you can't go back to not knowing. Whatever you do, you can't not know that again. And I think that that continued to lead me in a different direction than my brothers.

Walter Mosley: It's interesting, you know, because how do you become what you become? It's so hard to say. I learned a lot from my parents, but I don't know what that stuff is.

And that's why when people start doing these, you know, You know, they take your DNA, and then they tell you all this other stuff. I'm like, huh? It's like, this molecule is my relative, huh? Okay.

Helga: Which is different than being your family.

Walter Mosley: Yeah. Well, yeah, of course, it's certainly not your family. I mean, except in anthropological ways, I guess.

But, I think my father, wanted my life. As a matter of fact, I know for a fact, my father, when he was in fifth ward, so he was no longer a kid because he was taking care of himself, but he wanted to be a writer, and he wrote a story, a cowboy story, and he sent it to one of those people who publish that kind of stuff in Chicago.

There were a lot of publishers in Chicago then, and they never answered him, but at some point along the way he saw a story that was almost exactly like his.

I remember he told me that, and I just put it away. I felt a little bad for him, but not terrible. And then I became a writer. And it took me a long time to put those two things together. And I think that's why he wanted me to work in prison instead of writing, because he didn't want me to be brokenhearted.

I think it wasn't a mean thing he was saying, that he was trying to protect me. And then when I was successful, he's incredibly happy. It's like, but life is very complex. and why you're doing things, especially in kind of non connected world we have today. When I write about characters like Mouse and Twill in the Leonid McGill series, I always say, well, the best trait for a person to have to be successful is to be, to one degree or another, a sociopath.

Because in that direction lies success. Economic success. And we're all economics. I mean, everything about us. People say, are you a successful writer? And I'll go, yeah. And they'll say, well, how much do you make? Right. Most writers think this. I mean, it's what you live in. It's how you live. And when people say to me, what about you in writing?

I always say, well, you know, I'm a critical success. But I'm not a popular success. And I'm not, I don't, it doesn't matter to me. I don't want to change places with some popular writers. Because then I'd have to write the books they write, and I don't like those books.

Helga: And then what was your experience when you started making money?

How did it change your life and what was the effect on your writing?

Walter Mosley: For me, money is time. So if I have time to write and to think about the things I want to think and to read and to have my friends, then that's great. That's wonderful. And if I don't, you know, well, I have to work harder. That's all. And one of the things my father was always so mad about, we would talk, and he'd say, well, you know, Walter, how you gonna make a living?

I said, Dad, I don't care about money. I was such a California heavy. And he would be so upset, and he'd go, what do you mean you don't care about money? You know, when I was a kid, I said, yeah, I know, Dad, but I'm not there.

Helga: Yeah.

Walter Mosley: You're there. You're here. You're there. I'm here. You know? And, you know, because class is so interesting.

If you take a poor person and a middle class person and pull them out of everything they know and put them in a new place, they're going to end up in the same position in that new place. Because how to survive, it's part of their mind. And it has nothing to do with race or gender or anything like that.

It has to do with who you are. How you see yourself in the world and you impose that vision on the world. My dad didn't like that.

Helga: Mostly I see you in a hat.

Walter Mosley: I know.

Helga: How come?

Walter Mosley: I could take it off.

Helga: No. I just was curious.

Walter Mosley: Yeah, I wear hats. I have one ring. I have one hat. You know, I mean, it's like

Helga: And what's the starfish on your lapel?

Walter Mosley: Oh, it's just a button. I like to put buttons on my lapel. Men can have a little bit of jewelry. Is meaningless. Doesn't say what your marital status is, doesn't, doesn't say even how much money you have or anything like that. It's just, oh yeah, I put a pin on it.

Helga: Other than writing, is there anything that you do every day?

Walter Mosley: I draw a lot. I'm not a big reader, but I've been reading more and more, and I talk to people. Like, before I came here today, I was talking to Paul, and we were just talking about the big literary festival they had out in Brooklyn last weekend. But just normal, everyday stuff. I cook. I like to cook. Yeah.

Life has been very simple, and I've been very lucky in life. I mean, even discovering what you would really like to do is pretty difficult. Living in a capitalist system, which the whole world is, success, as we were saying before, always comes down to economy. And that may not be what makes you happy.

Helga: Thank you for coming. And thank you. It's been great.

That was my conversation with Walter Mosley. I'm Helga Davis.

Join me next week for my conversation with the Juilliard School's ethnomusicology professor,

Fredara Hadley: Fredera Hadley. Because in teaching about Black music, if you're going to do it honestly, you can't just teach strange fruit. You have to talk about that and say, Let's listen to this sublime and heartbreaking.

Breaking performance of it that Billie Holiday gives. No, no, no. You have to talk about lynching. You have to talk about the Northern response to lynching. You don't just get to have the song.

Helga: To connect with the show, drop us a line at helga at wnyc. org. We'll send you a link to our show page with every episode of this and past seasons and resources for all the artists, authors, and musicians who have come up in conversation.

And if you want to support the show, please leave us a comment and rating on any of your favorite podcast platforms. And now, for the coda.

What's that book on the table?

Walter Mosley: It's a book that's coming out in June. It's called Farewell Amethystin.

Helga: Do you want to read something from it?

Walter Mosley: Sure. I'll read like the first page.

How's that sound? That sounds great. Nah, nah, man. I said no. They want to kick her out of that school because she, a black woman, want the Constitution to practice what it preach. All kinds of white revolutionaries and, and, and, and activist teachers up there at UCLA, and they don't make a peep about them.

But Raymond, whisper Natalie Rumble, they say she's a Marxist, a communist. So? It's a free country, ain't it? My friend challenged. Raymond Alexander, Saul Links, Whisper, and I were sitting around the conference table in my office at the back of Renzel Detective Agency. Mostly on Monday mornings, we got together to discuss events in the news.

Monday was a good day because the rest of the week you couldn't trust that we'd all be around. At the top of the week, around 9. 30, 10 o'clock, My partners would migrate back with paper cups of bitter coffee in hand. For the past couple of months, Raymond, also known as Mouse, has shown up for this informal meeting.

This was an unexpected wrinkle. Saul and Tensford had once asked me to keep him away from our workplace because Raymond was a career criminal who practiced everything from racketeering to first degree murder. But that request changed on a Wednesday morning in the late fall of 1969. I was waiting for the rest of it.

Helga: Well, you want people to want more, you know. Yes, we do. Yes, we do.

Walter Mosley: If you do a book right, there's never a moment where you want to put it down. There are moments you have to decide, you know.

That's a good reason for a chapter break. Okay, I'm gonna stop here and I'm gonna start tomorrow.

Helga: Season six of Helga is a co production of WNYC Studios and the Brown Arts Institute at Brown University. The show is produced by Alex Ambrose and David Norville, with help from Rachel Arewa, and recorded by Bill Sigmund at Digital Island Studios in New York. Our technical director is Sapir Rosenblatt, and our executive producer is Elizabeth Nonemaker.

Original music by Meshell Ndegeocello and Jason Moran. Avery Willis Hoffman is our executive producer at the Brown Arts Institute. Along with Producing Director, Jessica Wasilewski. WQXR's Chief Content Officer is Ed Yim.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.