The Not-So-Sunny Side of Louis Armstrong’s Legacy

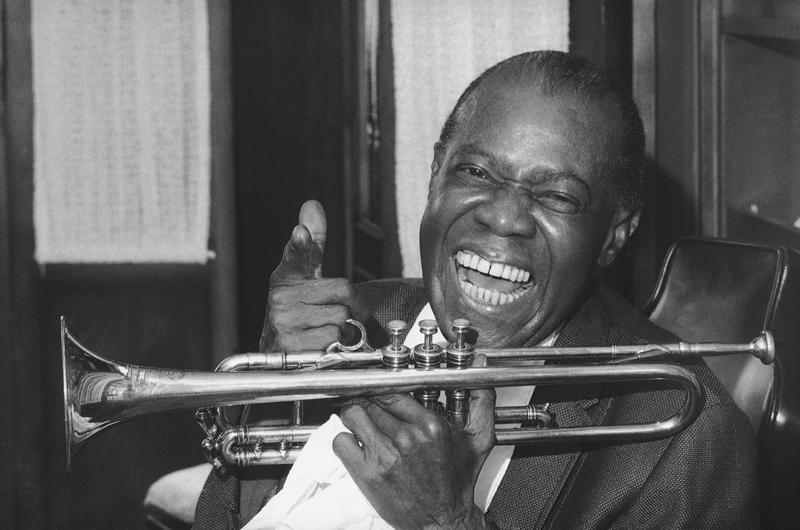

( John Rooney / AP Photo )

[music]

Kai Wright: It's Notes from America. I'm Kai Wright. I remember when I first really heard Louis Armstrong, really caught the feeling in his trumpet. I was in high school and for some reason, I had a cassette of maybe his greatest hits, I don't know, but it, of course, included his famous version of Sunny Side of the Street. It's the crazy trumpet solo that just gripped me. I also remember, something about Louis Armstrong didn't quite sit right with me. There was the big smile and the bug-eyed look and just an overall style and presentation that felt degrading, like minstrelsy aimed at white people.

I didn't know it at the time, but it turns out a lot of Black people felt that way about Armstrong, in particular, the generation that came of age right after him in the mid-20th century, alongside a new era of Black politics and culture with just a very different vibe. A conventional wisdom about him set in, but it's one that filmmaker Sacha Jenkins wants to challenge. Jenkins has spent decades chronicling Black music, in particular hip hop, as a writer and as a filmmaker. His latest project is a documentary called Louis Armstrong's Black & Blues. The film aims to reveal a side of Armstrong that we haven't really seen and often using Armstrong's own voice. I spoke recently with Sacha Jenkins about the project and about how a guy who spent his life focused on hip hop started thinking about Louis Armstrong.

Sacha Jenkins: Well, the nice people at Imagine Entertainment gave me a call and asked me if I'd be interested. I knew a little bit about Louis Armstrong but not what I know now. I started to dive into the research, and once I realized how amazing this gentleman was, not that I didn't know he was amazing, but coming up in the '80s, Public Enemy, Black Consciousness, what I knew from a distance about him didn't seem kosher to me. Doing the research, I learned a lot about Louis Armstrong. I was completely blown away by his story.

Kai Wright: At first, when you were first approached by the film, were you like, "No, he's not really my kind of person"?

Sacha Jenkins: I don't want to say I was like, "No." I was like, "Let me look into this." I didn't immediately say yes. I'm just very lucky to have gotten the phone call because it's such an amazing project. I've done a few films in my day, but none of them have ever received this kind of response, so I'm glad I didn't say no. I'm glad I said, "Let me look into this," and I'm glad that I did.

Kai Wright: Well, the film features many prominent voices, including Wynton Marsalis who shares his own complicated journey and thinking about Louis Armstrong. Let's listen to a little bit of that.

Wynton Marsalis: My father always said, "Man, you have to check Pops out." I was going, "Man, I don't want Pops [unintelligible 00:03:03]." In New Orleans, it was so much what we call Uncle Tom and goes on playing [unintelligible 00:03:07]. In my time, I hated that with unbelievable passion. When I was growing up, there's no way for me to even express the type of anger and hatred I had towards that type of behavior, so I could not appreciate Louis Armstrong.

When I left New Orleans, and I was in New York at that time, my father sent me a tape. He said, "I want you to learn one of these Pops [unintelligible 00:03:28]."

[music]

Wynton Marsalis: I put it on and I started to work on it. Man, I could not play this solo at all. Just the endurance of Louis Armstrong. He never stopped playing. He was always up around high Bs. When we got to the final course, I called my father. I said, "Man, I didn't understand about Pops." He just started laughing and he said, "That's right."

Kai Wright: There's a few things in there. We have that rejection of some of the style and presentation of Armstrong's early work, that it sounds like you were aware of as well but then that mind-blowing reaction to his music that so many people have. Let's first spend some time talking about the music itself and understanding that legacy. As you got to know him, what do you think he meant musically to you as somebody who has studied so much music? What do you think he meant to you?

Sacha Jenkins: When Armstrong was setting out to do what he did, Black people, and not much has changed, were being groomed to be servants. They weren't being groomed to be artists. To be an artist is a position of privilege that many of us obviously didn't have. What he represents to me is freedom. What jazz represents is freedom. We're able to be ourselves and express our feelings without someone telling us what to do or how to do it. That's what jazz is. If you look at it in that way, there's no civil rights without jazz. If you consider Armstrong the leading pioneer of jazz as a movement, then he's a petitioner of freedom.

He's a promoter of creativity and ideas and going beyond where we were able to go with those times as people of color. Looking at what a Renaissance man he was in terms of the art that he made, his singing, his humor, how he dressed, I can't name anyone in the modern era that has his level of talent, although someone at a screening said to me, "What about Stevie Wonder?" I'm like, "All right, Stevie Wonder is up there [crosstalk]."

Kai Wright: I was actually thinking Stevie Wonder is about the closest I can imagine.

Sacha Jenkins: Stevie Wonder is up there. Stevie is up there, but Armstrong is just, I don't know, not a normal person.

Kai Wright: Can we talk about the singing? You make the point in the film, a number folks do say that everybody who has sung pop since Louis Armstrong is derivative in some way. Could you break down what that means for folks? What was so new about his singing style that was so radical?

Sacha Jenkins: It goes back to this idea of freedom. A lot of the pop music, particularly created by white folks, was very stiff and by the books not very emotional. I think Armstrong brought a motion to the table and he brought a level of unpredictability with vocals. With the other stuff that was already existing at that time, you knew seconds before where the vocals were going to go and how they were going to feel. With Armstrong, it was like a roller coaster ride. He went in there and got on the roller coaster. You didn't know where it was going to twist or turn.

[music]

Sacha Jenkins: That just changed the game. People didn't sing like that. People sung by the books. He threw the books out. I think that's why he's had such a major influence on popular music because, before him, people weren't singing like that.

Kai Wright: In the horn itself, does it all boil down to just that he would hit those high notes like nobody ever before?

Sacha Jenkins: Yes. I don't think it's just the high notes. I think it's also his approach to soloing. Solos, oftentimes, are improvised and different every single time. His solos were like a Nike Swoosh. It was something to be perfected note for note. That idea of this freedom, for the most part, but then in the solos, developing it from the free idea and then refining it to a point where it was a science, I think that idea in and of itself lifts the precision of music that's made by people. I think it's something that is tough to live up to. Marsalis wrote them off at first, and then when it was time for him to try to play it himself, he realized how hard it was.

Kai Wright: You're right. I have to say what fascinates me when I listen to Louis Armstrong is, I'll be listening to a record at first, and at first, it'll sound so old-timey, and then at some point, my brain shifts and it feels like I'm in this weird avant-garde space. Do you know what I'm talking about? If so, what am I experiencing there?

Sacha Jenkins: It's really hard to describe, but it's otherworldly in many regards. It was something that was so new and original but really coming from someplace, not coming from a song, book, or something that's written down. It's really coming from somewhere really deep, and it's really coming from his life experiences which can't be duplicated by anyone. That's why I think jazz is so crucial. Most Black music is his reflection or a reaction to the environment and what he brought to the table. He brought his whole life to the table in every note that he played.

Kai Wright: One reason that Armstrong wasn't fully embraced by the generation of Black artists and fans that followed him is that he mostly avoided political conversations at a time when politics was very much a life-and-death business for Black people. He wasn't really part of the civil rights movement, at least not publicly, but Sacha reminds us of a moment in Armstrong's history that we rarely hear about. It was when he was already one of the most famous performers in the world and loved by white audiences globally.

In 1957, he was supposed to play a tour of the Soviet Union sponsored by the US government, but he canceled it in protest of what was happening in Little Rock, Arkansas, where white supremacists were refusing to allow school integration to move forward. When a reporter asked him about it, he offered some choice words for President Eisenhower, and it was all just very out of line with his public persona.

Sacha Jenkins: For anybody to call out the President is not an easy thing to do. The old me wouldn't expect that from him.

Kai Wright: I had never heard of it. I'm very familiar with the history of Little Rock, and I was not familiar with Armstrong's role in it. What do you think was going on for him at this moment? It was such a departure from what he had been doing previously in his public role. What do you think changed for him that made him speak out at that moment?

Sacha Jenkins: I think it's years and years of promoting the American brochure of life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness for all people, and I think he was just tired of it. He's being asked to be an ambassador on behalf of the United States and go to places like Russia and Germany and all over the world, and he's like, "You want me to represent America, but America is not representing me." I think he always had these opinions behind the scenes, but at that point, he felt like it was time for me to say something. He didn't just say something about anybody, he said something about Dwight Eisenhower, which, again, is not something to take lightly.

Kai Wright: I'm talking with filmmaker Sacha Jenkins about his documentary Louis Armstrong’s Black & Blues. Coming up, the complicated question of why Armstrong's early work has felt a bit too close to minstrelsy for some fans. Stay with us.

[music]

Kai Wright: Watching Sacha Jenkins's documentary, I learned totally new stuff about Armstrong's politics and his life away from the cameras, but I still felt uncertain about his early performance style and I asked Sacha about that. What about that minstrelsy stuff that Wynton Marsalis talks about? I have to say I didn't walk away feeling like I had a real answer to how Armstrong himself felt about that aspect of his performance style. What do you think he thought about that aspect of his performance style? Do you think he thought of it in the same way?

Sacha Jenkins: I don't think he thought of it. I think as it's explained in the film, the minstrelsy stuff was a thing. Ironically enough, even Black people were into it. It was like a popular form of entertainment. He's of the era where that was the popular form of entertainment. It was what was happening at the time, and it was the only outlet that they had. It was his truth at the time when he was coming up and he knew people who accepted it. He was a man of a different time. He's from 1901, New Orleans, which is like, his experience is much different from Miles Davis's. Miles Davis's dad was a dentist. Louis Armstrong's father was not a dentist.

His life years before a lot of these people is much different, and if he didn't do what he did, I call it a spiritual, tactical emotional jujitsu to be able to make these moves and keep moving forward, not many people can do that. Having to deal with that kind of crap, that kind of disrespect is very difficult. There's something to be said about how he handled himself. Does that make him an Uncle Tom? No. It makes him someone who was a survivor, who did what he had to do at the time he had to do it.

Kai Wright: You got a chance to use tons of archival tape and pictures from Armstrong's own collection which he was keeping in his houses in Queens. He turns out to be almost compulsive about recording himself and keeping a scrapbook of his life. What do you think that was about for him?

Sacha Jenkins: I think he knew that he was one of one. He knew that he was the first to do a lot of things and that if he didn't document it, who would have? Because of his archive, because of how meticulous he was, a lot of these things we have today. Who else was out there documenting Louis Armstrong? Nobody, not to my knowledge. He made his artwork with these collages, largely from newspaper clippings, but he also had the newspaper clippings and write-ups about him, some of which where they called him a monkey. In print, they referred to him as a monkey.

I believe this art that he made with newspaper clippings and stuff was a way to process how he was treated in the media. He understood. Most people would throw that away or wouldn't say being called a monkey in the press. He saved it. He had a foresight. In the film, we use these tapes. It's like 40 years, a lot of years of these tapes that he made at home, on the road with friends, with family, where he just spoke his mind or just taped conversations. It's the backbone of the film.

You really feel like you're knowing Armstrong because you're hearing directly from him, but at the end of the film, he literally signs off and says, "That was my life. There's nothing else I was ashamed of." Who does that? You know what I mean? Even just for themselves. That's why I joke and I say, "I feel like he was the co-director on this," because he just left everything behind that you would ever need to make a film of this magnitude.

Kai Wright: They're really remarkable tapes to hear someone so famous, so unguarded, literally in his underwear in his home with a tape recorder thinking out loud. It's an unusual thing to encounter. You've chronicled the lives of a lot of artists. What do you think is the role of artists in social justice movements?

Sacha Jenkins: Well, in the case of Armstrong, I don't think he woke up and said, "I want to be an activist." He woke up and said that he wanted to be an artist and for white people, white people can do that. A white person could wake up and say, "I want to be an activist," or they can just wake up and be an artist. In his time, waking up and saying that you want to be an artist was unheard of. He woke up, said he wanted to be an artist, but in the process of being an artist, he's up against Jim Crow, he's up against all these things that are anti who he is.

I'm sure in the back of his mind at some point he realized that he was in a position to say and do things, but at some point, you just want to be an artist, you don't necessarily want to have the responsibility of your whole nation of people who look like you. That's a lot of pressure.

Kai Wright: It's a lot.

Sacha Jenkins: If he knew that was the case going into it when he was 14, learning how to become a musician, maybe he wouldn't have done it. Maybe he would have said, "Man, I've got to be in charge of all the Black people too? I don't know if I want to do this." You know what I mean?

Kai Wright: "I'm just going to play the horn on the streets of New Orleans and leave it at that."

Sacha Jenkins: Yes. "If I got to be the keeper of all Black people, I don't know if I'm going to want to really do this." The role of artists is to make art. That's his number one job. His number one job is to be an artist, and through his art, hopefully, people can pick up on the bigger themes and things that reflect his life and what he wants to change inside of the art. Now, as an artist, if you want to go beyond that with words and actions, that's fantastic, but I don't know that it's necessarily the job of an artist outside of the art that they make to go beyond that. I think it's up to the artist.

Kai Wright: You've made documentaries on Wu-Tang Clan, on Cypress Hill, on Rick James, a complicated man to be sure, and now Louis Armstrong. Is there anything that ties all this work together for you?

Sacha Jenkins: Louis Armstrong and Rick James and RZA from Wu-Tang, there's not much of a difference. They all come from these environments that are tough. They all come from environments that there isn't much opportunity. What they do have though is their creativity and their intelligence, and they apply their creativity and intelligence to make music. People might argue that jazz and hip hop are two different genres, but I've come to believe that when it comes to Black music in America, there's no genre, there's just Black people reacting to the environment and creating in the environment, things that reflect the environment.

[music]

Kai Wright: The film Louis Armstrong’s Black & Blues is now streaming on Apple Plus. Sacha Jenkins is also working on a series of documentaries about 50 years of hip hop. Yes, 50. We're going to have him back to talk about that later in the year, so I look forward to it. Notes from America is a production of WNYC Studios. Find us wherever you get your podcast. Mixing and music by Jared Paul. Production, editing, and recording by Karen Frillman, Vanessa Handy, Regina de Heer, Rahima Nasa, Kousha Navidar, and Lindsay Foster Thomas. I'm Kai Wright. Thanks for hanging out with us tonight.

[music]

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.