Why So Many Are Stuck in the “Other” Box

Regina de Heer: What is your race?

Tessa: Caucasian.

Samantha: White.

Jason: My parents are both from China, so, Asian.

Jonathan: I'm biracial, African American and white.

Stephanie: It's a really hard question. Hispanic isn't a race, so I can't say Hispanic. I usually just put white and Black when I do applications, and categorize under Caribbean.

Jaswiry: Mixed.

Regina: Mix of what?

Jaswiry: I'm Dominican, so I would just say I'm not sure what I'm mix with, so I just say mixed.

Manny: I don't know, it's confusing, because I am Jewish, but of course my skin is white, so on surveys, things like that, will probably have to write white.

Alejandro: Hispanic descend, Dominican, I guess. I feel like whenever somebody asks for race, it's always a confusing question.

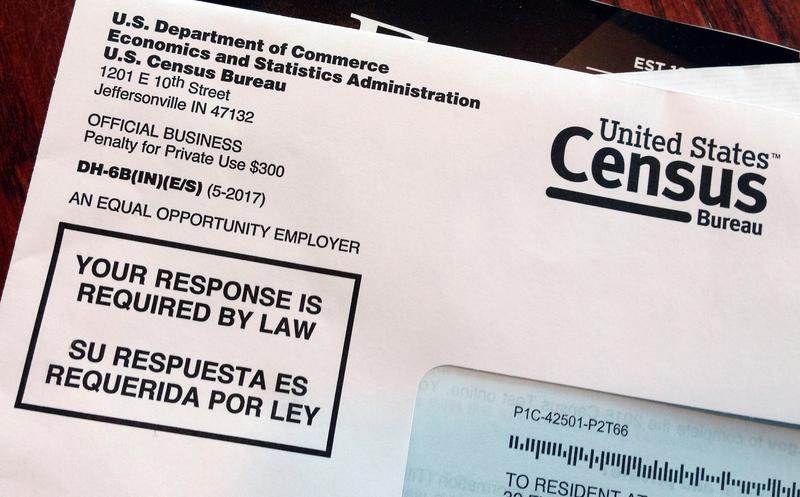

Kai Wright: Welcome to the show. I'm Kai Wright. Question number nine on the 2020 census asked you to identify your race. This past fall, when the Census Bureau released our collective answers to that question, it revealed a tremendous shift in how Americans think about our racial identities.

First off, the number of people who identify themselves as multiracial exploded. More striking, to me at least, the census declared that the second-largest racial group in the country today is 'some other race'. Now, I've to say, as someone who has been writing about race for 25 years, that blew my mind. What's it mean? What motivated people to check that box? Frankly, should I care? I mean, will there be material consequences for, say, how we use census numbers as a result of this stat?

As this election year heats up, we're all hearing more and more about congressional redistricting based on the 2020 census. The process is, of course, wildly consequential and increasingly confrontational. You are, after all, allocating power through manipulation of numbers. Redistricting is not the only way the census doles out resources and power. It influences how public money is spent, how and where businesses are developed, even how medical research is conducted. On a whole nother level, it tells us who we are as a nation, literally, which is maybe why we're always struggling with its imperfection.

We want a perfect headcount, we want a perfect classification. The closest we can get to it is an approximation. As that some other race stats suggest, the imperfection of this process presents a deeply personal conflict for some folks.

Tonight, we're going to try to understand this amorphous new racial group by talking to a data expert, one who herself struggles with all of this box-checking around racial identity.

Mona Chalabi is a data journalist who uses illustrations to make huge sets of statistics understandable. Her podcast is called Am I Normal?, and it is published by Ted and launched this past October.

Mona, thanks for joining us.

Mona Chalabi: Thank you for having me.

Kai Wright: As we started thinking about this topic, we found one of your illustrations that made us realize that you were exactly who we needed to talk to about this. It's from your Instagram, it's this reinterpretation of that meme, where a finger lingers over two buttons, making a hard choice. In your illustration, it's about government surveys, and it's sort of you trying to choose between four buttons that say, Black, white, Asian, and Hispanic, and you are quite vexed by the choice. What's the story behind that drawing?

Mona Chalabi: I guess it came out of my own personal experiences of what it's like to face, not just government surveys, but form after form after form in workplace environments, at school. Even at the dermatologist's office, where I don't see myself on the form, I'm not one of the available boxes. The result of that is that it means I have to, like many people, I have to do a sideways step in terms of my identity. That sideways step is super weird because I am clearly not any of those other identities that very often appear on the form. What I'm left with is a choice. I could either choose the thing that feels closest, which is really bizarre to be choosing between white, Black, and Asian when you're Arab, or I can select other, which is very often one of the choices that's available, but I think comes with its own weird set of choices about what that means to select other, or I could just not participate, which is something that a lot of people choose to do.

Kai Wright: Notably, it seems like this illustration is one of the more popular ones you've done, at least on social media. What do you take from that? I guess that it is quite common to feel the way you do.

Mona Chalabi: I was really surprised, actually. So many of the comments are from people who feel like they really, really relate to that. Either because they're also from other racial and ethnic groups that aren't represented on most forms, or because they themselves were Arabs. I was just surprised how many Arabs follow me on Instagram. I guess I'm surprised by the number because we don't really know how many Arabs there are in the US, let alone how many follow me.

Kai Wright: That's a striking thing you've just said by itself, we don't really know how many Arabs there are in the US.

Mona Chalabi: No. The range of estimates is pretty wide. The Census Bureau put the number at around about 2 million, and the Arab American Institute estimate it's closer to 3.7 million. That's a huge difference.

Kai Wright: It's double.

Mona Chalabi: Yes.

Kai Wright: Let's talk about your own sort of background. I mean, your parents moved from Iraq to London, which is where you were born.

Mona Chalabi: That;'s right, yes.

Kai Wright: You said in one interview, up until, I'll quote, you said, "Up until I was in my mid 20s, literally, the only Arabs that I knew were my immediate family." How'd you think about your racial identity at that time? Did you think about it at all?

Mona Chalabi: I thought about it all the time. I was forced to think about it all the time by people asking me all the time, "Where are you from?" right from when I was super young. I was always aware of it and always thinking about it. I think sometimes without community, it's hard to know what a thing means, except by defining yourself in opposition. Again, this is tied, I guess, to that idea of government forms.

My identity was other. I just knew that I wasn't white, I knew that I wasn't in the majority. I also knew that it wasn't these other racial-ethnic groups like Black, like Asian, like Hispanic. What are you left with? Once you've done that process of elimination, and all you are is other, what are you left with? I think sometimes you figure that out in community. As I said, I didn't really have that community, because it was just me and my immediate family.

Kai Wright: Were those categories even apply? If you are in a community and says, Okay, I'm in an Arab community, would those racial categories even apply? Setting aside whether there is, one, a racial category for you, is a racial category even relevant?

Mona Chalabi: That's interesting, because I think what happens is, when you are in community, different categories apply. The set of labels transforms, it becomes Russian doll. Let's say I'm in an all-Arab space with people who only identify as ethnically Arab, all of a sudden, Arab falls on the floor, because it's not relevant. All of a sudden, in that context, you become Egyptian, Lebanese, Iraqi, the categories transform.

Kai Wright: Did this change when you came to the United States? You came to the United States as an adult, did your relationship to racial identity shift as a consequence?

Mona Chalabi: It's a really good question. I actually moved to France before I moved to the US. In France, my Arab identity was incredibly important, because of France's history of colonialism and racism. It's interesting, they could immediately identify me as Arab much faster, I would say, than someone in the US. Then they are interested in which country, because what they were essentially trying to understand is, is there a historical link between us of extraction, exploitation.

Kai Wright: Are you a good Arab, or a better?

Mona Chalabi: Exactly. Then fast forward to moving to the US, I think the thing that was really, really interesting for me, is that my Britishness was the filter through which my Arabness was viewed. Even if I go into a store or something, I feel like I might be treated differently to a white customer. The moment I open my mouth, this whiteness is conferred on me just by virtue of having a British accent, because now all of a sudden, it's assumed that I'm educated, it's assumed that I have money. All of the things that are not assumed of people of color suddenly get given to me because of the way that I speak.

Kai Wright: You mentioned earlier that people would sort of ask you, where are you from in London, but that's certainly a thing we talk about a lot in the United States, is this sort of, if you don't fit a racial category the way the guessing game immediately begins. I imagine you've seen a lot of that.

Mona Chalabi: Definitely. I don't know the eagerness with which people want to choose the right country, is just so fascinating because I want to understand what each of those guesses mean to them. What do those guesses mean to you? What does it mean for me to correct that? Again, it's also interesting, just the specific set of baggage that comes with each of these identities at a specific point in time and in a specific geography in the context of the US to say that my parents are Iraqi is a bit of a conversation killer, not just because no one's able to be like, "Oh, I love Iraqi food," or, "I go there all the time on holiday." There's nothing to say there. Obviously, because of the political history of the US, some of the buzzkill was just like, "Oh, we "invaded you", and I don't know what to say next.

Kai Wright: Do you think also that your name is part of it?

Mona Chalabi: Definitely. I was going to mention that earlier on, this idea of race and ethnicity being flexible and complicated, and not only how pronounceable your first name is, but it's the specific combination of your first and last name, and how ethnic does that make you sound, how white does it make you sound. Actually, both me and my sister were specifically given names that my parents really, really hoped would help us to assimilate a little bit better, which is-- I don't know. I think about how important that act is, of choosing your child's name, and how it was constrained by the realities of just trying to survive and trying to make life a little bit easier.

Kai Wright: It's funny, because I was given a name explicitly to make me more Black. I don't know, is that a fair way to put it? I was born at a time when Black parents were choosing African names, often just out of a book, to try to own Blackness as opposed to Negroness in the United States.

Mona Chalabi: And to reclaim pride, so like, "Yes, we won't be ashamed."

Kai Wright: I think it's true for a lot of immigrants of color, our immigrant families of color, this choosing of names to try to downplay the otherness.

Mona Chalabi: Even language as well, which is obviously a complicated aspect of identity. It sounds bizarre to say I feel more Arab, the better that my Arabic language skills are, but it's true. We were taught Arabic when we were young, and then we stopped going to Arabic school, and actually, honestly, it was just a shame to speak in public. All of those skills atrophied, and I was ashamed, even if my mom spoke to me in Arabic in public, especially after 9/11, because you don't want to be other, you want to be normal.

It was only when I became much, much older that I realized that actually in our cultures and in our societies, actually normal is just a synonym for white, most of the time. If I was really, really striving to be normal, I was trying to get towards someplace of whiteness, really.

Kai Wright: I'm talking with Mona Chalabi, a data journalist, illustrator, and host of the podcast, Am I Normal? We'll take a break and talk more about how last year's census revealed a whole lot of people who are trying to make new space for themselves outside of the white, Black binary that has always defined the United States. Stay with us.

Kousha: Hey, this is Kousha, I'm a producer. This episode talks about some aspects of race and identity that are fuzzy, personal, tough to talk about, and tough to answer. It's a topic I'm sure a lot of you listening might have thoughts about too, so we want to invite you into the conversation. Which part of this episode sparked something for you? Are you ever mistaken for another race? Do you correct people, or as Kai was just wondering, what do you make of the fact that some other race has become such a popular choice on the census? Or are there questions you wrestle with on this topic that we didn't cover?

We'd love to hear what you think, and maybe do a follow-up segment based on your responses. If you could, please record a voice memo on your phone and email it to us. Our address is anxiety@wnyc.org. Again, that's anxiety@wnyc.org. Thanks, and talk to you soon.

Regina de Heer: The census was delayed in 2020 to 2021, but it's not the only questionnaire of the sorts that ask you to identify your race and check a box of predetermined categories. We're asking people around the park, is it challenging for you to answer or put yourself into one box?

Jason: I identify as Mexican American. I think I've always had a very hard time checking a specific box when there's a list of races and a list of ethnicities, and I identify just with the ethnicities and not necessarily a race. If you were to ask me to check the box for Caucasian, which I guess is the closest one, for me, it just doesn't feel right.

Manny: I'm Jewish, but it's confusing, because of course my skin is white. Surveys or when applying to college or a job, will probably have to write white.

Regina: You identify as white yourself?

Manny: I don't know. It's not so binary, I know a lot of Jews that aren't white. I don't know what they would say. I don't know how to answer that question, really.

Alejandro: Race, Hispanic descent, Dominican, I guess. I feel like whenever somebody asks race, it's always a confusing question. I always pick other, and it does make me feel bad. I go to college, too, so being in school, every test is always other, other, other. It sucks. It definitely sucks.

Puja: Way back when in elementary school and high school and you have to do those standardized testing things, I think that was a little more confusing than because I distinctly remember they didn't even have an Asian category, because I'm Indian. That's the only time I think that I've paused, per se. Other than that, not really, because they also have the Asian option on the Census.

Victor: I'm born in Mexico, but I was raised in California. I also grew up in a white neighborhood. Whenever I saw those questionnaires, I'd always put others and I was just ashamed that I had to write my own ethnicity/race in the other box. My nickname was Frijoles in school. Whenever I would choose that other--

Regina: What does that mean?

Victor: Beans, it means beans in Spanish, which is very racist. When I checked that other box, I was like, I'm hitting that stereotype that they keep identifying me as. That I'm just Coco, I am an other to them. Luckily for here in Washington Square Park, it's a huge diverse thing, so I'm never ashamed to showcase my heritage, my culture, my ethnicity, my curls, for one, because it's part of my culture. I know that that box, it was always a triggering moment for me.

Regina: Do you ever have any pause when having to fill out those forms? Why or why not?

Issa: Actually, I feel like you asked me the perfect question, because I'm from Mexico and Spain, so I'm Hispanic. Sometimes I have trouble understanding why Hispanic is in a separate category. I feel weird checking off the white box because my skin tone is white, but that's not reflected on paper. I still have three last names. It makes me feel like I'm wiping away my heritage a little bit.

Regina: Does that happen in your regular day-to-day life? Do you find that people first see you as one thing over the other or put you in a box before you even get the chance to identify yourself?

Issa: Yes. It gets a little more complicated because it's like a battle that is more rooted in myself rather than outside. When I go to Spain, for example, I've been discriminated against, for my accent because my accent's very split between Mexican and Spaniard. I've been discriminated against by my own family, which growing up, I felt a little ashamed for it. Then in Mexico, I would be ratted on from the other side of my accent. Now just to be labeled as white, it's just a little bizarre to me.

Daniel: Yes, it's a little challenging for me, because I'm from Israel originally. I googled it, actually, and apparently, Israelis consider themselves as whites, but technically I'm Middle Eastern, but I see myself as white because that's what Google says.

Regina: Google says you're white, but do you feel white yourself?

Daniel: No, I do not feel white.

Regina: Can you talk more about that?

Daniel: Culture-wise, I'm not sure how to explain in a politically correct way, and I don't know, I just feel Israelis are different in their culture.

Kai Wright: I'm Kai Wright, and we're talking this week about identity and how it's become an increasingly complicated thing in the United States. According to last year's census, the second-largest racial group in the country is, "some other race." Data journalist, Mona Chalabi, who is host of the podcast Am I normal? has been thinking a lot about that fact.

As an Iraqi woman, raised in London, having lived as an adult in the United States, she's intimately aware of how fraught the choice can be when you're asked to check a box.

Mona Chalabi: I think so much of my own sense of identity is just like, I still don't really know what it actually means to be Arab, in some respects, because it's a made-up concept. All of these are made-up concepts, but all I can really, really say very, very concretely is that I know in my gut, it's completely inaccurate for me to check that box white on the survey and yet, if I'm presented with options like white, Black, and Asian, I don't know, maybe white is the closest thing to it.

Kai Wright: When people are trying to guess where you're from, how much do you think that's relationship to trying to guess how white you are? How close you are to whiteness?

Mona Chalabi: Yes, because when people have guessed, for example, like Spain or Italy, then that reduces the differences between us, and it potentially provides an opportunity against the say, "This is where I go on holiday, that's the food I eat."

Kai Wright: In the US, do you see any connection between race and faith, and did that make identifying with a single race more complicated for you here?

Mona Chalabi: I think there are big connections, and I think that actually in a really concrete way, that affects the numbers. There are huge differences in the estimates of the size of the Arab American population, and part of the reason for that is that we, as a community, are especially likely to feel skeptical and concerned about government surveys. There are many groups in the US who feel especially distrustful of government surveys, and faith honestly becomes a big part of that.

If you're living in a society that is incredibly Islamophobic, when you're presented with a survey like that, you know that Arab is a bit of a byword for Muslim. If I check Arab, I might be outing myself as Muslim too. Note that that's necessarily the case, there are a whole load of Muslims who are not Arab, and there are many, many Arabs who are Muslim, but still, they have become slightly synonymous with one another.

Kai Wright: Yes, I would say they're inextricably tied in the United States, the idea Arab and Muslim, despite the fact that the vast, as I understand it, the majority of Muslims in the world are not Arab.

Mona Chalabi: Exactly.

Kai Wright: It's just getting another striking way in which we construct these things that have no bearing on reality.

Mona Chalabi: I'm so glad you referred to this as constructing these things, because I do think that the way that we live, sometimes it is easy to lose sight of the fact that this is a fiction that we have created that has served both practical and obviously incredibly negative purposes. If you take the example of a government survey, like the census, that does perform really, really important practical uses, and I can understand why these really basic categories have been constructed, but at the same time, they are made up, they are a fiction.

Kai Wright: We say this often, that race has been made up, but help people understand what we actually mean by that. It's kind of ironic that categories like Arab are more real, in some ways, at least, things that are tied to a geography or a national origin versus the white and Black that have dominated the idea of race in the US.

Mona Chalabi: In order for white and Black to exist, actually, they require a constant imagining, a constant collective imagining each time that you encounter someone to make this leap of like, therefore you are this based on--

Kai Wright: Based on your skin color and the way you speak, the way you carry yourself.

Mona Chalabi: Exactly. These things have become real because we collectively, continuously make them real by the way that we live. It makes them real, it makes them have concrete consequences.

[music]

Kai Wright: We have to talk about the census itself. Let's start with the history of the census, because the backstory is super important. I believe it began in the 1890s, right?

Mona Chalabi: It actually began earlier than that. It began, the very first US census was conducted in 1790.

Kai Wright: Oh sure, I didn't know that.

Mona Chalabi: Yes, and actually its basic purposes are not that different, why the census is used today. The results were used to allocate congressional seats, electoral votes and funding for government programs. The one additional reason actually why they did it back then, was also to find out how many eligible men there were that could potentially serve in the US military, which arguably is also another purpose of the census even today.

The thing that's really notable about that census back then is, we are talking about how problematic the racial and ethnic categories are today, they were obviously much, much worse than problematic doesn't even come close. There were six categories that were used on the very first census in 1790. They were, I'm just going to quote the actual language here, "Free white males of 16 years and upwards", and again that was to assess the country's potential industrially and militarily, free white males under the age of 16 years, all free white females, all other free people, and then "slaves."

As you know, enslaved people were not counted as a full person, they were counted as three-fifths of a person. Other notable emissions from that list include Native Americans who also weren't counted at all. It's also really, really interesting. I didn't know this until I was reading up before this interview, that Thomas Jefferson expressed skepticism over the final count, and it's just so interesting that the skepticism has been baked into the census right from day one.

Kai Wright: From day one.

Mona Chalabi: For him, he felt like 3.9 million inhabitants was an undercount of how many people there really were in the country.

Kai Wright: Well, it definitionally was based on the categories you described, it was in fact a vast undercount.

Mona Chalabi: Exactly.

Kai Wright: It didn't count any of the native people who already lived here.

Mona Chalabi: Undercounted the Black population.

Kai Wright: By three-fifths.

Mona Chalabi: Yes. Then just the other thing that is really interesting about this percents I didn't realize was that the results were published in kind of public squares, and people had the opportunity to go and read them and double-check they were correct before they were finalized, and I think there's something that's really beautiful about that, that isn't included in data gathering right now. Imagine if we had an opportunity to see the census data of how your community was counted, and have more direct input about what those categories are, or potential errors in the count before it's finalized.

Kai Wright: Baked into the beginning of the census is, this fight over the count. Also, from what you're saying, they're baked into the beginning of this census, is deciding who is white, who is male, and who is something not white and not male.

Mona Chalabi: Exactly, and by extension, it's also counting who deserves government resources, who deserves the right to vote, who deserves representation. Again, that's just as much true today as it was back then. It's so interesting to watch how those six categories have shifted and expanded in the 200 years since then. The one category that has remained the same ever since 1790 is white, and beneath that, you see all of these shifting moves of how Black people are described, are they described as Black? Are they described as African American? Are we just going to say Asian, are we going to divide into that and look at that in finer detail. Are we going to add Native American, but the one consistency is white. That is the thing against which we are defined and categorized.

Kai Wright: What's also then interesting is that while whiteness has been static, the idea of it has shifted. Who gets to be in it does shift.

Mona Chalabi: Exactly. I'm sure you and many of your listeners are aware of the history of different immigrant populations, be they Irish or Italian suddenly being absorbed into this category of whiteness, and often, it was pragmatic, and it also makes a big difference again to things like political representation and government funding.

I think white elasticity is a really fascinating, and at times quite dangerous concept. I think it comes back to this idea of if whiteness is synonymous with normal, it becomes amorphous and malleable, and we are always being defined in these really, really concrete ways. Being white is like water is fluid. It can fit into all of these different spaces.

Kai Wright: I've always kind of subscribed to the theory that there really is actually only white and Black in America, that because those are casts, not races, despite the language we use, and you're being sorted into one of those two casts. I guess, I wonder, do you think that's fair to say from someone going back to that drag you have where as an Arab who's like, "Actually, none of these categories make sense to me."?

Mona Chalabi: I really, really hear that there's literally just white and Black, the way that America operates. I think because I'm so concerned with statistics, and because that's what I look at all day, it's sometimes hard to escape some of that nuance. If we look at something like, for example, household wealth, we know that that is so radically different for, say, Asian Americans compared to Black Americans, that that category of Black versus white doesn't make sense in that context.

The reasons for that are so evident historically. I think what you see when you dive into the statistics is actually these nuances in terms of outcomes, genuine life outcomes for different racial and ethnic groups within the US, and that's where, again, it gets really, really frustrating for me as an Arab because I never get to understand that nuance from my own community.

Kai Wright: Because the statistics is don't exist.

Mona Chalabi: All Arab Americans-- Yes, the statistics just don't exist, so, all Arab Americans typically poorer than white Americans, are we more affluent? Do we have better access to government programs, less access? Until you establish that baseline, it is impossible for you to advocate for yourselves. It is impossible for you to make an ask if you can't prove that systemic racism exists against your community. That's really hard. I hate saying that even as I say it, because I don't want to for a second-- For example, Kai, if you were to tell me about an experience that you've had of racism. I don't want to say, wait a second, I'm not sure I buy it, let me check the statistics.

Individual experiences and personal narratives count, they should be believed. Yet again, when it comes to actually advocating for yourself and trying to create systemic changes that are more durable across generations, you have to be able to prove systemic prejudice that has happened across generations as well.

Kai Wright: Nearly 50 million people identified in this last census as some other race, and this part of this that is what blew my mind, makes it the second largest racial category in the US now. I'm just trying to understand what to take from that.

Mona Chalabi: I take from that, unfortunately, that, A, the existing racial and ethnic categories do not fully capture reality. There are a lot of people who simply don't see themselves on the list. B, unfortunately, skepticism of government and public institutions in general is very high. I suspect a lot of those people who have checked that box actually other boxes are available to them, but they would prefer to not answer. I think fascinatingly, a lot of white people might now be inclined to check that box.

Kai Wright: Say more about that, why.

Mona Chalabi: This is my impression, again, not necessarily based on statistics, or I really should look into more concrete studies on this. I did read a really interesting study a few years ago in the American journal of sociology on this. I think that due to racism, as well as force propaganda, there are a lot of white people who are under the impression that 'positive discrimination' is resulting in this nirvana, and I use the word positive discrimination in quote marks as well. I don't even think that is the appropriate language to describe programs that are used to redress injustice.

I think there are many white people who feel like they are constantly missing out on some opportunity at work, at school because they are white. Increasingly, I suspect white people are uncomfortable with checking that box, and uncomfortable with their whiteness.

Kai Wright: Wow. The idea that has been made this the second largest racial category in the United States, if true, would certainly explain a lot about our political moment. Or other version of it is, and I suppose if we were taking callers, maybe this will be a question for our listeners, is, does it mean white people are rejecting whiteness?

Mona Chalabi: If they are, isn't that massively problematic, Kai? You don't get to just say you're not white. You don't get to just ditch your history. That's another way of saying I don't want to have this conversation. I'm just going to choose to not be white. No, no, no. You are white. You are part of an existing racist system in the US, and that is not making an accusation that you as an individual are racist. It's acknowledging the context in which we are all operating, and you don't get to just say I'm not white.

Because as soon as you do that, again, the ramifications of this are huge. If you, for example, don't want to say to HR, I'm white because you're worried that it's, I don't know, you're going to miss out on some job promotion, that means that we are not going to get accurate numbers on how often actually white people are getting promoted within the workplace. Unless we understand that better, how can we get a better measure of racism in the workplace? You don't get to opt out. That's not fair. That's the definition of whiteness that you get to choose, isn't it?

Kai Wright: Yes, absolutely.

Mona Chalabi: That is the definition of whiteness that like, this doesn't serve me anymore. I'm not going to use this label. No, I also do worry whether this is maybe two in the weeds. I do actually worry about how companies like 23andMe, these ancestry tests are reinforcing this idea, actually, that race and ethnicity has a real scientific grounding that you can be 23.4% Black and 22.5% Arab. I think that very often people don't quite understand just how shaky that science is, and that actually sometimes we are just a few steps away from eugenics when we are drilling into that stuff. We're really not so far off. It actually really frightens me.

Kai Wright: I find it a little unsettling as well. I wonder how much the popularity of this genetic testing also explains the growing number of people who identify as some other race, like how many people have had their genetics tests that has changed the way they think about themselves.

Mona Chalabi: When I think of the tests, I think of two broad consumer groups that have very, very different motivations. Actually this is, again, a simplification. There are many, many other groups that take it. Some of the people who take those tests are African Americans who had their history violently robbed from them and are trying to reclaim it and understand it. Some of them are white people who are actually looking for a way to either escape their whiteness or add more nuance to it.

Because, again, I think for some people, whiteness feels a little bit uncomfortable right now, and they would much rather identify as Irish, as 15% native American, as whatever you like, but just to call themselves white feels a little bit uncomfortable, I would say to some Americans.

Kai Wright: Which again, I'm not sure if that's a good or a bad thing, because I also hear some good in that people are interrogating whiteness, but I…

Mona Chalabi: They're not interrogating it though, Kai. If they were interrogating it, that's one thing. They're trying to escape it. That's not an act of interrogation to spit into a tube and to now be like, "Hey, I'm Native American," where's the interrogation there?

Kai Wright: We'll take a break, and then Mona Chalabi and I will continue our own interrogation of the existing boxes for racial and ethnic identity in this country, and they're incredible imperfection. Why's all this even matter? That's next.

[music]

Regina de Heer: Do people ever confuse you for any other race, and do you correct them?

Stephanie: Yes. I've gone confused with Middle Eastern before, and I do correct them because I'm not Middle Eastern. I do understand the confusion because I guess a lot of people are racially ambiguous, so I get it, but it's a bit ignorant to say that.

Manny: I don't know how you define race, but ethnically, people always think I'm Greek, or Italian, or Spanish, or Latin descent, whether I come from South America. They think I come from all over. I have dark features, so I get that all the time, but if you're just saying, do they think I'm not white, then no. People think I'm always white.

Alejandro: Yes. I have a unibrow that I shave, and I have my unibrow Muslim, or if I wear my durag, because I have ways, I'm Black. It always happens, and you get accustomed to it, and of course I correct people, yes, and I'll say, Hey, I'm Hispanic or I am Dominican. At the same time I've grown numb to it, to the point where it's like, I just sit with it and I'm okay with it, I guess.

Jaswiry: I've gone to Middle Eastern, I've gone to Mediterranean, people usually think I'm mixed Black and white. I think that, because we're in America, I feel forced to not just identify as Dominican. I have to acknowledge, especially because I'm very racially ambiguous, it's just it's life like hear you should.

Regina: Do you ever get confused for another race?

Kousha Navidar: I do get mistaken for many different races. Folks just assume that I am whatever that local place is, and it's not every place, but it's a lot of places. In the question of race, it's defining that when you don't have a definitive answer, it feels just uncertain. It's more on me to find and define those answers for myself.

Kai Wright: I'm Kai Wright, and those were our producers, Regina de Heer and Kousha Navidar, out in the streets asking folks about their racial identities. I've been talking with data journalist, Mona Chalabi, about the racial ambiguities and complexities and anxieties that last year's census results revealed. Nearly 50 million people chose "Some other race" when asked to identify themselves, making it the second largest racial group in the country.

As a data nerd, Mona is concerned about the practical implications of this fact.

You have mentioned several times the consequences of the numbers and the census, and that's something you've very passionate about. I think it's something that people continue to struggle to wrap their heads around. Let's talk about that, about why these numbers are important, [chuckles] what we use these numbers for.

Mona Chalabi: I think people hear all the time, things like congressional seats and government funding. It's also counting who deserves government resources, who deserves the right to vote, who deserves representation. That still feels like these big vague concepts. The truth is, unless we have an accurate understanding of population counts, we kind of don't really know anything, really. It is literally every single aspect of our lives. I am using those population counts every single day in my work. Yes, they was writing an article about how pet ownership has changed during COVID. In order for me to understand how pet ownership has changed, I actually need to understand the number of people in the US, because all I have is data on the percentage of US households with cats or dogs, and the average number of cats and dogs per US household. Now, if I want to estimate how many cats and dogs there are in the US, I need to know how many people there are in the US.

That's obviously a really, really light example, but at the other extreme a few weeks ago, again, I was writing about Omicron and COVID. How can you understand the rate of spread of a deadly disease with just understanding the number of cases? No, you need to have that basis line of how many people there are in the US in order to understand the gravity of that. Again, you can say that you want to opt out and you don't want to participate in those government surveys, but you really are very often disempowering yourself, because by not being counted, all it means is that your particular community is less likely to get funding and get power in all of these really, really concrete ways.

Kai Wright: Like with COVID, every time you see that stat, X number of infections or X number of deaths per 100,000 or per 1,000.

Mona Chalabi: Exactly.

Kai Wright: That per 1,000, that's the census.

Mona Chalabi: Exactly, exactly.

Kai Wright: If we can't say per 1,000 Arabs, we can't tell you the COVID infection rate amongst Arabs in the United States. It could be the worst epidemic in the world. We don't know.

Mona Chalabi: That's a really, really fantastic example of where, yet again actually, Black and white don't make sense. We need to understand transmission rates within specific communities to have really focused responses.

Kai Wright: Someone talked about this on your podcast and used a phrase that drove this in a more metaphysical level that I find really powerful that these numbers matter, because "What is observed is recorded as truth."

Mona Chalabi: Even if it's not the truth, it is recorded as such, and by being recorded as such, it has huge implications for our lives.

Kai Wright: It has implications for our personal individual lives too. You were telling our producers a story about going to the dermatologist in which data mattered. What happened?

Mona Chalabi: I can't remember why I went to the dermatologist, but I went to a dermatologist in New York, and sitting in the waiting room, I was handed a clipboard, and the number of possible racial and ethnic identities was more than I had ever seen before. I'm going to estimate there were like maybe 50 different boxes on that form. Everything you can possibly imagine, not just Asian, for example, it was Singapore, Taiwan, Hong Kong, all listed there, and I still wasn't on the form. Whatever, I check the nearest available alternative. I think I had to check other in that respect, and headed into the office to go and see the dermatologist.

Exactly as you say, this kind of nuance of someone's face together with their specific name, she looked Arab, and on the name badge, it was pinned to her chest, I recognized it as an Arabic name. I said to her, "Oh, can I ask, where are you from?" She said, "Oh, I'm Egyptian." It was her practice. I said, "As an Egyptian woman, why have you not included Arab on the form outside?" She was like, "We just download these from online, and I used the one that was available and it didn't include any of our Arab identities on them." She said to me, "Makes a difference, right?" Arab skin types are different to other skin types, and that would've made a difference in terms of how she treated me.

Kai Wright: Then this echoes throughout the medical field. We hear about birth rates, we hear about maternal mortality rates, all of these things that would impact what treatment decisions a doctor would make. They're invisible.

Mona Chalabi: Exactly. It's not just treatment, it's also diagnosis. I don't know if you're aware of this massive push, which is actually finally gaining some traction to change medical textbooks so that other skin types are better represented in medical textbooks. If you are only used to identifying a rash on white skin and a Black patient comes in with a similar rash, are you trained to identify that rash on Black skin? Again, this is where numbers come up. If you are making a case to publishers, you're making a case to book agents, we need to publish this with these different skin types. You need to know how many people have those different skin types in order to make your case, and without the numbers, you are just saying, "We need to do this."

Kai Wright: What is the fix to this? Is it a endless list. I don't want to sound like one of those conservatives, but is it an endless list of boxes to check? Do we get rid of the box checking at all together? That doesn't seem like what you're arguing for. What's the right way to do this?

Mona Chalabi: I think the right way is just an expansion of the categories we have. We know that male and female does not cut it as these two simple boxes. The truth is actually four boxes to include transgender and non-binary folk on there, still is an approximation of reality, but it is a whole lot better than what we have right now. The same goes for race and ethnicity. We can expand those categories while still actually being slightly imprecise, while still not getting exactly the truth, but doing a better job than we are right now.

Kai Wright: But then what do you say to individuals, both with race and gender identity and all kinds of identity, who feel like even the phrasing check the box, it puts me in a box, who do not want to be in a box, and who react to the whole conversation in that way? What do you say to those folks?

Mona Chalabi: I get it. Even the description of the Middle East, the way that we're placed on a map is in opposition to the West. Middle East of what? It doesn't even make sense as a piece of language. However, it's like sometimes in life, you have to hold your nose and get on with things. In this case, I'm holding my nose and selecting the box Middle Eastern if it's there in front of me, because it is going to mean that my community can get better access to crucial resources. You have to work with what's there. The other thing that is really crucial to say that I haven't said yet, I understand people's skepticism, particularly with the last administration. I don't know if that's too politicized to say.

Kai Wright: You can say it if you want, and we would agree.

Mona Chalabi: Government statisticians are nonpartisan. The chief statistician of the US holds their job across multiple presidencies. This is continually the case, and the algorithms and the mathematical formulas that are used to count people are neutral. I'm not denying for a second that politicians can play with the numbers. They can put a spin on them. They can try to publish them in different ways. Trump, in particular, tried to change the way that categories were counted in order to reach different conclusions, but the way that the number--

Kai Wright: In order to erase people of color. The goal was to minimize the number people of color in the country.

Mona Chalabi: Absolutely. Actually there was a plan to add Arabs to the last census. Trump was partly responsible for that not being the case. With the hope, obviously, that many of those somewhere between 2 and 3.7 million Arabs would instead check white and artificially inflate the size of the white population in the US. I understand all of those concerns. However, government statisticians are politically neutral, and I understand it's a bit of a leap of faith, but it's a bit of an essential one, honestly, in order to be counted.

Kai Wright: It's so interesting because even in the course of this conversation, I just keep struggling with this tension between-- we talk about race rhetorically so often. It's such a rhetorical conversation for so many people, because again, it is such a construct. It's such a concept. The way we live it is so individualized, is the consequence, and yet, when we get into this data conversation, it is so concrete.

Mona Chalabi: Exactly. Yes.

Kai Wright: There's just this tension between the reality of race being totally not concrete, and the reality of data being super concrete, that I don't know what to do with, because I am moved by your case that, yes, but we need the data because that's the world we live in. It's just, I don't know, there's just something maddening about those two facts.

Mona Chalabi: I guess I would just add to that. I think that even exists in the natural sciences more than we're willing to acknowledge. Actually, in the natural sciences, still sometimes we're approximating the truth, but we know it's necessary in order to develop drugs, in order to create environmental plans. I know it's a bit of a leap to compare that to race and ethnicity, but the natural sciences also approximate the truth. I think sometimes we lose sight of that. We think the social sciences are all made up, and the natural sciences are perfect and objective. Actually neither of those statements is true.

Kai Wright: Mona, I thank you so much for making this time and for your work and your thought on this.

Mona Chalabi: Thank you so much. Thank you.

[music]

Kai Wright: Mona Chalabi is a data journalist and host of the podcast Am I normal? Let me flag those questions you heard us asking people in the street coming in and out of the breaks. If you want to chime in as well, please do. Record your answer in a voice memo, and email it to me at anxiety@wnyc.org. That's anxiety@wnyc.org.

[music]

Kai Wright: The United States of Anxiety is a production of WNYC Studios. Our theme music was written by Hannis Brown and performed by the Outer Borough Brass Band, sound designed by Jared Paul. Our team also includes Emily Botein, Regina de Heer, Karen Frillmann, and Kousha Navidar. I am Kai Wright. You can keep in touch with me on Twitter @kai_wright, and, of course, you can find me on the live show next Sunday at 6:00 PM Eastern. You can stream it at wnyc.org, or tell your smart speaker to play WNYC. Until then, take care of yourselves, and thanks for listening.

[music]

[00:51:32] [END OF AUDIO]

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.