The Russian Activist Maria Pevchikh on the Fate of Alexey Navalny, and the Future of Russia

David Remnick: Welcome to The New Yorker Radio Hour, I'm David Remnick. A couple of weeks ago on the program, I was talking about the anniversary of the invasion of Ukraine along with the historian Stephen Kotkin and he said something that really struck me that Vladimir Putin is destroying both countries Ukraine, and Russia. The horrifying campaign against Ukraine began a year ago but for quite a long time Putin had been dismantling Russia's civil society and with it, its international reputation and really its long-term economic prospects. One of the darkest moments along this path came in 2020 with the poisoning, the attempted murder of Alexei Navalny.

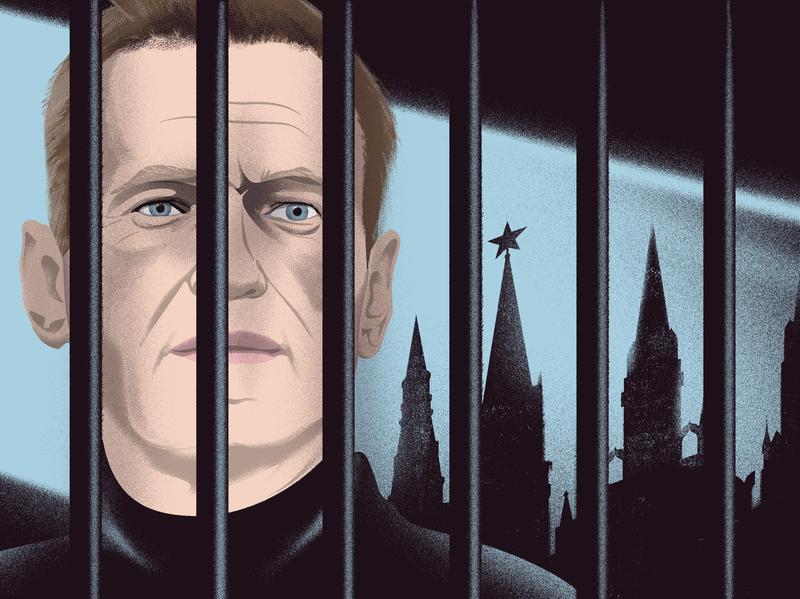

Navalny is a prominent dissident and opposition leader and he and a team of investigators illustrated in startling detail the corruption of Putin himself and his circle of aides and oligarchs. For his efforts, Navalny was poisoned with a nerve agent called novichok which was almost certainly done by the FSB, the security services. He survived the attack, and he's now being held in a Russian penal colony. If Russia has a future after this disastrous time, Alexei Navalny may well be pivotal to it. One of his closest colleagues is Maria Pevchikh. Pevchikh helps to run his anti-corruption foundation and she's the head of investigations and media.

She also served as an executive producer of the documentary called Navalny, which is nominated for an Academy Award. Maria, as anyone who has seen the documentary film, Navalny, knows, you are a very close comrade in arms with Aleksei Navalny, you’re an investigator, you speak to the public, you're an advisor. I'd like to begin simply by asking you a sociology student at Moscow State University, you were working in what you once described as the most boring job in the world both in Moscow and London for a tobacco company. How did you meet Navalny and why did you decide to join an enterprise like this which is part journalistic, part activist, part political?

Maria Pevchikh: Well, I studied politics at London School of Economics. From very early Putin's years, from his first term, it was very, very visible to me that something is going awfully wrong so I was looking for an outlet, I was looking for some force that I could join and help this force along the way to move forward and Navalny seemed like a great option who is most likely to be able to deliver change.

David Remnick: What did Navalny represent to you in terms of political ideology or opportunity?

Maria Pevchikh: Navalny represented a real person in politics. It was so new and so fresh back in the day because we were brainwashed for as long as I can remember myself, we were brainwashed at the university and school levels that there is no politics, you shouldn't be involved. Your vote doesn't change anything, you are not deciding anything. Leave this for the big guys or another one, politics is dirty. The only way to be political you can be some political strategist and make big money out of political campaigns. Political participation back then wasn't cool. It was great and cool to be apolitical, people were almost bragging about it.

David Remnick: That was also what politics depended on. In other words, that's what Putin depended on. The deal of society was you can pursue this new, shining possible prosperity, at least if you were lucky enough to be in Moscow, St. Petersburg, and a few other places and not in the provinces, but stay the hell out of politics and if you entered politics, trouble will come your way as so many journalists and budding politicians discovered to their peril.

Maria Pevchikh: Correct. Then there was Navalny who was young, who was so good at putting complex things in simple words, the way that he wrote about corruption, about financial crimes, now this is a rather boring topic, isn't it? The way that he was phrasing things, the way that he was framing that debate was so attractive. He could interest anybody and in the topic which normally isn't really interesting, but Navalny's charisma, Navalny's conviction, and just his ability to organize people around him, that definitely worked its magic and we saw it on a larger scale just two years later in 2013 when he ran for the Mayor of Moscow.

Essentially what worked for me back in 2011 was displayed on a larger scale in 2013 when we saw thousands and thousands of Muscovites leaving their day jobs and good day jobs to go and stand in front of a Navalny branded poster that said vote for and then Navalny as the Mayor of Moscow. Those guys, I didn't know, they worked in big international consulting firms and investment banks but in the evening they would show up at our headquarters and sort out leaflets in four separate piles. That would be their assignment and they would spend the evening volunteering with most basic tasks at our headquarters.

David Remnick: The regime was tolerating this, there was still some allowance for dissent at least for a while.

Maria Pevchikh: Correct. I think that's what infuriated Putin and what eventually led Putin to the decision to kill Navalny is the fact that whatever Navalny did being investigations or political activity or running a campaign, that it worked and it attracted an audience that Putin assumed was his. Navalny’s weight has changed a lot in 2017 when he started touring around Russia for campaigning to be allowed to run for the presidential elections in 2018. This was when the biggest mess about Navalny was busted that Navalny is for Muscovites, that Navalny is for this middle class, upper-middle-class guys well-off people from St. Petersburg and Moscow.

Then Navalny started traveling the country organizing those rallies in, I don't know, 80, 90 different cities and tiny little towns. Sometimes we would only be allowed to have this rally organized on the outskirts, literally in the middle of a forest next to a cemetery and people still showed up. Whoever is responsible for internal politics in Kremlin they realized shit, even the people who we thought are the core Putin voters they like Navalny, they show up, they go in the middle of the winter when it's -35 degrees, they go just to listen to the guys speaking from the stage.

David Remnick: At what point did Navalny and your team get the sense that they would no longer be tolerated and Navalny’s life was in danger?

Maria Pevchikh: Every time when I heard Navalny giving an interview I sat right outside of his office and I could overhear many journalists coming in and out and I don't think there was one interview where he wasn't asked, how come you're still alive? How come they still haven't killed you? I clearly still remember Navalny’s face rolling his eyes seeing, "Guys, I don't know. I'm tired of this question. Stop asking. I don't know why I'm still alive and why they haven't tried to assassinate me." I don't know why they have decided to do this when they did it in August 20, 2020.

We know, from our investigation together with Bellingcat, that they started planning this when Navalny started to travel Russia for the presidential campaign. This is when the surveillance started, this is when the FSB operatives together with the chemists and doctors started to follow Navalny. Have they tried to do something before, have they tried to poison him earlier? Maybe. Maybe it just didn't work.

David Remnick: I have to say and I hope I don't mean this in any way derogatory. The attempt on Navalny’s life it brought to mind in an almost perverse way a James Bond movie where you're watching the movie and instead of shooting James Bond very simply, they do things like dip him slowly into a pool of piranhas or something just for the sake of the movie, obviously. Why go to all this crazy trouble of poisoning his underwear? It's not like anybody was going to be deceived on who was behind this killing.

Maria Pevchikh: Well, the plan was that they poison Navalny, he gets on the plane, the flight is rather long from Tomsk to Moscow around five hours, probably more, that would be enough for him to pass out, and if the plane didn't do an emergency landing, he would have been dead in the next 45 minutes to an hour. Forever and ever this would have remained a mysterious death. They've had by the time Navalny collapsed and where by the time he was hospitalized in Omsk, they already had a premade theory of what has happened. They were starting to say every state-owned channel, every state-owned newspaper, they would say, oh, Navalny drank a lot the night before. Navalny partied a lot a night before, alcohol, drugs, you name it and within hours of the poisoning, they had a theory that it's either Navalny's health or it was me who poisoned him and that was a big alternative plot as well. Hugely promoted by the--

David Remnick: Tell me about that. What was the story about you trying to poison Navalny?

Maria Pevchikh: That's actually now when the whole alcohol and drugs thing didn't really check out at all and nobody really believed it. Now, according to the Russian propaganda, the main theory that they share for the Russian audience is that I poisoned him. I have a very clear association with the foreign states. I lived in the UK for most of my life and nobody really knew what I'm doing, who I am. I was there on the trip and also as Bellingcat found out recently, the group of FSB operatives and the poisoners, they have separately followed me on the days when they didn't follow Navalny.

I found pictures of myself from surveillance taken on the morning when I left Moscow to go to the airport to fly to Siberia. They were following me and not other members of our team. In the beginning of the trip, they weren't following Navalny, but they were following me. Their cell data shows that they showed up at my hotel two days before the poisoning.

David Remnick: He gets to Germany and viewers will see this in the really remarkable documentary film, Navalny, and he physically recovers, which is not easy and there seems to be no question about it, to return to Moscow. I want to hear the calculation of returning to Moscow. He had to know that his arrest upon arrival, it was almost a sure thing. Talk to me about that discussion of returning to Moscow.

Maria Pevchikh: There was never a discussion. There was never process of choosing and waiting scenarios and deliberating on that. One of the first things that Navalny said when he woke up from coma is that he is going home. He is a Russian politician. He has built his career and he gained his popularity by telling people that they shouldn't be afraid. How hypocritical would that be if you ask people to be brave, to be courageous and then yourself, you make not the most courageous choice?

Our only deliberations were around the topics of how to run the anti-corruption foundation without Navalny. We spent days and days discussing every scenario. In case, I don't know, what happens if he's under house arrest? What happens if he is in prison for a couple of years? What happens if he's in prison forever? What happens if he gets killed? What happens if nothing happens, if Navalny is just free and goes peacefully and home directly from the airport?

David Remnick: Was the most likely scenario was that he would land at the airport and be arrested?

Maria Pevchikh: Yes, it was most likely, yes. It wasn't for sure then.

David Remnick: I'm surprised from time to time talking to people who are well connected to him, that he's able somehow from a prison colony to communicate to the world through Twitter that there are fairly reliable reports on the condition that he's in and the conditions in which he lives. Tell me how that works.

Maria Pevchikh: Navalny is currently being investigated, actually no, he's already in the legal process of the next court case. That legal status allows him to see and communicate with his lawyers who can meet him and discuss anything from the defense strategy to the content of the actual case. His lawyers are able to visit him regularly and this is how we know how well he's doing. We know his general state of health.

David Remnick: Which is what?

Maria Pevchikh: We know, whether he's--

David Remnick: What's his state of health?

Maria Pevchikh: It's not good. He has been poisoned by a nerve agent, by a chemical weapon. The consequences of such poisoning are not known. Not many people survived. There aren't no studies.

David Remnick: The long-term consequences of the [unintelligible 00:15:22].

Maria Pevchikh: Yes, because your entire nerve system just shuts down completely and entirely and then thanks to the German doctors, they managed to restart it. He managed to come back to a decent state of health, he was exercising. He was doing his daily walks and all of that, but nobody knows how this actually affects a person long-term. On top of this, I'm not sure whether it's related to Novichok poisoning, but perhaps because it's only started after that, Navalnyy started to have severe back problems, severe to an extent that at some point during the first months of his imprisonment, he stopped being able to walk.

David Remnick: Do you think Putin wants him to die in jail the sooner the better?

Maria Pevchikh: Oh, I think Putin wants him to suffer a lot first and then die in prison. Of course, he wants that.

David Remnick: In your late at night, when you're thinking about this, do you imagine for him that end or the opposite, the end of the resolution of Nelson Mandela who's released into the light and comes into political light?

Maria Pevchikh: It took him a couple of years to be released. No, I'm not dreaming about Nelson Mandela scenario either. It took him a little bit too long.

David Remnick: You've been very accurate in some of your predictions over the period of time that we've been talking about. How do you see this playing out?

Maria Pevchikh: I try to convince myself just not to think through this scenario of Navalny being poisoned and killed in whatever way and in prison. I think this is a self-defense mechanism, I'll be honest, David. I've lived through him dying in front of me once and I didn't like that experience at all. I don't want to come back to it and I know exactly how it felt. I remember these days during his poisoning very vividly and this were the scariest days of my life by far.

I don't see much points in just sitting there dwelling and looking into darkness and saying like, "Oh, what would I do when he gets killed? What would I do?" Can he be killed tomorrow? What I know he might be dead right now. We don't have a way of finding out until the next morning, but this is not how I operate. I like to operate in a different assumptions. I genuinely think it is possible to get him out.

David Remnick: How do you see that happening considering the war in Ukraine, the militarization of Russian society? What possible motive would there be? I hate to say it, for Putin to make that decision.

Maria Pevchikh: All of this can play both of an advantage and a disadvantage for Navalny. The situation is so chaotic, specifically because of the war as the likelihoods of Navalny being released when the war end is high. I think it's almost certain. I'm almost certain as well, that at any next president have to Putin, even if it's the worst one, you can imagine, even if it's Prigozhin from the Wagner Group, but I'm sure that the next president would release Navalny.

David Remnick: Why?

Maria Pevchikh: Because it's a symbolic, it's an easy win. It could be a condition, a mass release of political prisoners could be a condition for lifting some sanctions. Could be a part of any peace talks and reparation talks and all of that process, post-war process that is inevitable. There are many, many scenarios.

David Remnick: Maria, in Soviet times, there were a whole tribe of people in Moscow, but beyond who eventually became known as the people of the sixties [foreign language] and they played an odd game. They were both in the establishment and also saw themselves as children of the-- secret speech by Nikita Khrushchev and the post-Stalin era and hoping for reform. Think of them what you will, they became the pillars of a top-down revolution.

What's happened now is a lot of people, hundreds of thousands of people who are in many ways the best and the brightest, have left the country. You've lived in the UK a long time. The exile now has been enormous. These are people who were the potential liberal forces and intelligentsia of not only Moscow but many other places. First of all, will they return and how do you feel about people that in your mind have compromised on the margins of their activity?

Maria Pevchikh: Those are two separate questions. With regards to those people who left, I feel in the long term, I feel sad that they left because I'm being realistic. I understand that not all of them will come back, even when Russia is free of Putin, and when Russia is in its post-war period. I think some of them will, probably most of them will return but we will lose a good 20% of brightest, smartest people who have managed to quickly restart their lives abroad, find new jobs, start new businesses, and just start their life from scratch. I'm being realistic, yes, they probably won't return. I will be personally convincing them.

I will be asking them and I will be trying to make them return home and contribute to [unintelligible 00:21:39] and building the beautiful Russia of the future. I understand that perhaps I'm not convincing enough and some people will choose their new life. As for the second part of your question, the people who compromised, I try not to judge. I will be too rude or just too judgmental here, I'm sure that you can guess what I actually think about compromising with Putin's power, about being ignorant, about closing their eyes to the facts, to what was happening to us, to the opposition and just continuing to run your theatre or cultural center or something like that.

David Remnick: Or radio station.

Maria Pevchikh: Yes. All I'm saying here is that let's now all gather and draw a very simple conclusion. This strategy didn't work. They've lost their radio stations, TV channels, and whatever they were trying to save they lost and along the way they've lost the integrity and the honesty.

David Remnick: I hate to go from the extremely serious to the seemingly benal, your film is up for an award an Oscar. I think it may well win. I'd like to see it win quite frankly.

Maria Pevchikh: Yes, me too.

David Remnick: There will be a moment with the biggest audience imaginable, with a couple of minutes, you thank your agent, the usual thing. What do you want the world to know in the broadest sense?

Maria Pevchikh: From day one of Navalny's imprisonment. My main job alongside investigations is to climb on the highest mountain and scream and shout from the mountaintop Navalny, Navalny, free Navalny. That's literally the most important thing I can do. That's my way of trying to save his life. The Dolby Theatre stage in Los Angeles, the venue where the Oscars are being held, that is the stage that the entire world will be watching during that evening. It really doesn't matter whether you get to say something from the actual stage holding the little golden man or off the stage during the press conference, the attention is still there. It is literally my job to grab that attention and to point it, not at myself, but at Navalny.

David Remnick: Maria Pevchikh is a Russian activist and investigator. She's an executive producer of the documentary Navalny about the jailed opposition leader, which is nominated for an Academy Award, and it's streaming right now on HBO Max.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.