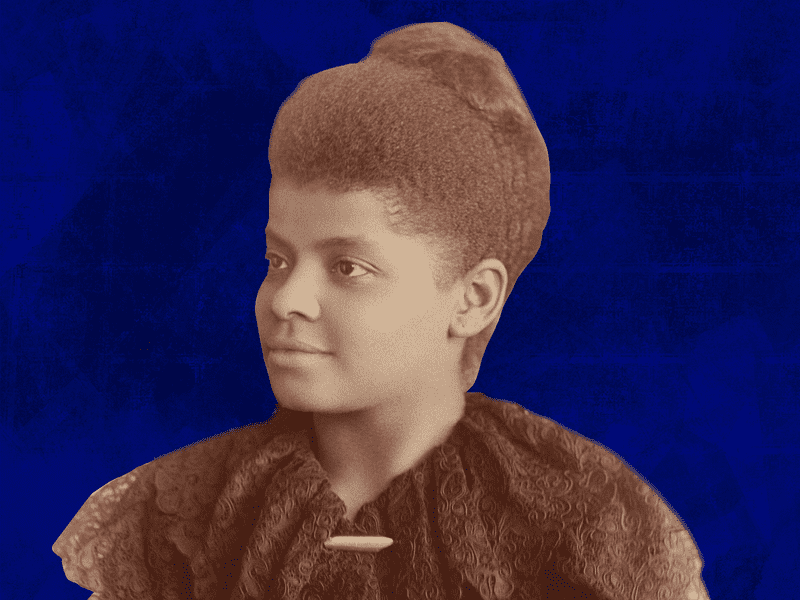

The Life and Work of Ida B. Wells

KAI WRIGHT: Hey everybody. I hope you heard the big news? This year’s Pulitzer prizes have been announced and one of my personal journalism heroes has won: Ida B. Wells. It took more than a century, but Ida’s work on lynching has been officially recognized as some of history’s most consequential journalism.

And we made an episode about Ida Wells in a previous season of this podcast. So I figured this is a good moment to share that with you again. Because I suspect that Ida is still one of those iconic historical figures that people know by name… but not necessarily understand her real contribution to history. Which is a shame, because Ida’s work and her ideas are just so, so relevant right now.

[Theme music]

I’m Kai Wright, and this is the United States of Anxiety, a show about the unfinished business of our history, and its grip on our future

KAI: Introduce yourself. Who are you?

PAULA GIDDINGS: Hi. I'm Paula Giddings, writer, biographer of Ida B. Wells.

KAI: I spoke with Paula back in 2018, during the midterm elections. Her spectacular biography of Ida Wells is the definitive source, and it’s as much a coming of age story as anything else.

PAULA: As I looked at her diary -- she has fragments of a diary that are available -- you begin to see what's really inside of her. She wants to transform a society that isn't treating her very well, actually. And she wants to transform herself. What's very interesting and comes out in the diary is that she has a lot of anger, and she knows it will destroy her if she can't get a hold of it. So she works very hard to transform that anger into something positive. And this kind of urgent activism that she has, I think comes as a result of that.

KAI: Ida Wells was born enslaved, but grew up free, during the Reconstruction era -- in those decades following the Civil War, when the United States rewrote its Constitution to create a truly interracial democracy. And for a time, those were more than words on a page.

Ida came of age in a place where that promise, that ideal of everybody getting a fair shot at making a life for themselves, it was palpable and real.

PAULA: Memphis was called the Chicago of the South because there was lots of industry going on and lots of opportunity. And black people had opportunity as well, and were very optimistic in those early years after Reconstruction. Business was exponentially increasing, black business. Schools -- blacks actually had a higher attendance rate in the Memphis public school system than whites did.

KAI: And there were people making money.

PAULA: And people were making money. And there were restaurants. There were industrial businesses. There were small stores. The other thing that's going on Kai, is that because of education, I mean, illiteracy is dropping precipitously. In fact, so much so that there is now a market for a black press for the first time in the 1880s, because there are enough black people who can read. You know, Ida’s Minister, Benjamin Imes said, I mean, he said, “Look, we're in a Christian country with a republican form of government. What else can there be but progress for us?” And this is only one generation out of slavery. But they thought that this kind of prejudice and hatred and certainly slavery was something of the past. That there were still remnants of it, but this was old now, that they were moving forward.

KAI: They would, of course, soon begin moving backwards again. Ida would witness the federal government’s retreat from Reconstruction. She would face the surge of violence that southern whites used to regain absolute power over politics and industry. And by the time she was in her early 20s, she would begin to lead her community’s response to all of this.

Her choices and her ideas mark a pivot point in the history of black politics -- which really is to say, in the history of the United States, there is before and an after Ida Wells.

[Sound of a train moving]

Fittingly, her political career began in a fight over space -- the literal space that she occupied as both a black person and as a woman in public.

PAULA: Well she actually enters public life because of an incident on a train in Memphis, Tennessee. Think about a railway car that's a first class ladies car. And the gender specifics are very important there.

KAI: If you were gonna be a high class woman, you weren't really supposed to be running around in public at all. But if you had to be out, you confined yourself to respectable public spaces.

PAULA: Free of smokers, free of bad language, free of any drinking or alcohol. And women who rode in them were to be women of good character.

KAI: And there was a pecking order. You could only be a truly first class lady if you were white. If you were an upper class black women, there was something called an “accommodation” car.

PAULA: Separate but equal. And in fact materially, that car is exactly the same as the ladies car. The difference is there's no gender designation. The difference is that there's smoking and drinking. And what happens - what made people really angered - is that whites would leave the ladies car and come and smoke and drink in the accommodation car, in the black car, and then go back when they finished to the ladies car. Well, in 1883, Ida’s going to get on the train. She sees smoke in the accommodation car and to her mind, this means that this is no longer a first class car. So she makes her way to the ladies car.

KAI: She’s paid her first class fare. She certainly considers herself first class caliber. And so with the full certainty of her social station, she sits down in the white ladies car. Now, it’s 1883, less than a generation after the Civil War. She’s just 21 years old. But when the white conductor tells her to leave, she refuses. Firmly. And repeatedly.

PAULA: The third time he asks, he actually tries to extricate her out of the seat physically. She grips the seat with her feet in front and fights to hold on, and scratches the conductor and actually bites him. You know, there's a court case later, and in the court case he actually testifies, he said, “She looks like a lady now, but I bled freely!”

KAI: That court case turns Ida into a local celebrity. She fights it for years, and ultimately loses.

But in black Memphis, that’s not the point. It’s not about Ida winning or losing. It’s about the fact that she just refuses to cede one inch to the idea that she is a second class citizen. And that is thrilling to watch.

PAULA: As a result a local newspaper asks her to write about her experience.

KAI: And that invitation changes the course of American history. Because Ida Wells discovers her calling.

PAULA: She says in journalism, I found the real me. And this is a person who's really searching for herself. But in journalism, she finds her voice. And so watch out everyone, after that. [Both laugh]

KAI: Thousands of black people were lynched in the years that followed Reconstruction. Ida is known today for investigating hundreds of these murders -- that’s why she got her Pulitzer Prize. But she didn’t just gather the facts. She used them to develop an entirely new set of political ideas about how black people could get truly free in this country -- ideas that differed sharply from those of the Reconstruction era, and from the values she once held dear herself.

[Outdoor construction sounds]

BRYAN STEVENSON: Hello, it’s great to be with you. My name is Bryan Stevenson… [Fades out]

KAI: To understand Ida’s evolution, I went down to Montgomery, Alabama, to visit the nation’s first memorial to black people who were lynched. Bryan Stevenson, who runs the Equal Justice Initiative, he created this memorial to flesh out the history of lynching with names and places and stories. He wants us to feel the terrorism that ended Reconstruction, that established the segregated society we still live in today.

KAI: Well let’s go in.

BRYAN: Absolutely.

KAI: It’s an open-air space, walled in, but outdoors. They’re still finishing construction and you can hear the city, just beyond the walls. But suddenly, it’s somehow really distant. There’s open sky. There’s a winding path. There’s a big, grassy hill. And the monument itself sits at the top of this hill. It almost menaces us as we climb toward it. As we reach the top, I can hear a waterfall running in the distance and we enter a forest of, I dunno, these weathered pillars.

BRYAN: These are six foot monuments. They're made out of corten steel. And in the elements, when it rains, it causes them to oxidize. And so you see marks and streaks and they become this really rich, important variation of brown and copper and they replicate, in my mind, the complexion of the African American community. And because they're six foot, they have a very human form.

KAI: It’s honestly terrifying. The floor slopes downward and the monuments -- hundreds of them -- begin to hang over our heads. Each one with the name of a county etched into its steel, along with the names and dates of each person lynched in that county.

BRYAN: You get a sense of these communities by the number of lynchings: One in Monroe - Montgomery County, Kentucky. Alcorn, Mississippi has five. Wilkinson County, Mississippi has eight. This is Amite County, Mississippi. The first lynching is documented, Simon Jenkins, in 1877. The last one, Eugene Bells, in 1945. That's decades of the threat and menace of lynching hanging over African Americans in that community.

KAI: Eventually, we get to the monument for Ida’s home: Shelby County, which encompasses Memphis.

BRYAN: And what you immediately notice about Shelby County, it has dramatically more lynchings than any of the neighboring counties.

KAI: There’s a reason for that. Shelby County had a huge black population. It had been a big player in the slave economy. And when freedom came, a lot black people stayed. And they were optimistic.

BRYAN: You had formerly enslaved people who had skills. Who had trades. Who were used to hard work. When they got their emancipation when they won their freedom they didn't say, “Let's get revenge. Let's retaliate.” They said, “Let's find a way to create a community with our former slave owners and oppressors, where we can all be at peace.”

KAI: Now, just pause and think about this: Ida is part of the first generation of black people to grow up free in the South. And that freedom comes with a really big asterisk. Because black people are considered less civilized than whites, by nature -- like, scientifically. This is a mainstream, noncontroversial idea. So, of course this generation really wants to prove it can be just as civilized as white people.

PAULA GIDDINGS: I mean, so many of us, we don't realize that black people were emancipated during the Victorian era.

KAI: Right.

PAULA: And that character, in a sense, character is like destiny in this period. And the idea -- the rights of first class citizenship, people feel it needs to be earned. There's nothing inherent there.

KAI: And in the early days of Ida’s journalism career, these are important ideas to her. She fills the pages of her newspaper with messages about black achievement and independence and success, and about looking to the future.

PAULA: Get education, accumulate wealth, you know, become this kind of first class citizen, as is defined by the society. Be progressive. There's really nobody more progressive than black people in this period of time, because they really believe in progress. And they’re very hopeful for progress, obviously. And she is a part and parcel of that idea.

KAI: It's very familiar, honestly.

PAULA: Absolutely. It still exists, still exists.

KAI: It's one of the things we talked about in the first season of this podcast, that when you look at African Americans and immigrants, you see people who were positive about the country.

PAULA: That's right.

KAI: Whereas all of these Trump people were so negative about the country.

PAULA: Exactly.

KAI: And that's a very similar divide as 100 years ago.

PAULA: Absolutely. Absolutely. Which is why history is so -- which I find so many answers to what's happening now in history. You do see these patterns, because there's a certain character to the country. And it repeats itself over and over again.

KAI: And there are certain values that endure. The striver ambitions of Reconstruction-era black people, they’re actually the root of what we now, derisively, call “respectability politics” -- this idea that black people oughta be more like the Obamas. And early in her career, Ida Wells embraced these ideas heartily.

She is after all, quite a success herself. She’s the first black woman ever to be editor in chief and publisher of a major city newspaper. And she’s become part of Memphis’s black elite. I mean, she goes to the right church, she dates the right kind of guys. But there’s this one piece of it all that just really bothers her. Because, you see, if the black community is gonna prove that it’s just as civilized as white people -- by white people’s standards -- then that means something quite specific for black women.

PAULA: There's something called the cult of true womanhood, in which women were supposed to be pious and pure and submissive. The true woman had those kinds of characteristics.

KAI: At least as defined by those times, in the late 1800’s. But that ain’t Ida Wells. Which actually really bothers her. She beats herself up about not measuring up to this standard of womanhood.

PAULA: And she's trying so hard. Some of her people she looks up to are women who are very feminine, who are very refined, and who seem to have a very even temperament. She of course is completely opposite! She has a mercurial temperament. She gets enraged very easily.

KAI: She hates that about herself. In her diary, she calls it her “besetting sin.”

PAULA: She's trying so hard to live up to a certain ideal. But then she will finally break through it, when she has to follow the logic of lynching.

KAI: When she realizes, white civilization is a lie.

Her awakening comes when the violence of the era finally touches people in her own life.

BRYAN STEVENSON: Three incredibly bright, entrepreneurial, smart men -- Calvin McDowell, William Henry Stuart, and Thomas Moss -- that created a grocery store.

KAI: A very successful grocery store, in an integrated neighborhood on the outskirts of Memphis. And across the street from a much less successful white-owned store.

PAULA GIDDINGS: The People's Grocery is one of these entities that is so symbolic of the rise of black people in Reconstruction. It's actually a co-op.

KAI: With more than a dozen investors, led by Thomas Moss -- who, it turns out, is a very good friend of Ida Wells.

It all starts in March of 1892, with a playground dispute.

[Fighting sounds]

PAULA: A black boy and a white boy are playing marbles. They get into a fight, they get into fisticuffs. The father of the white boy comes and starts beating on the black kid. This brings out the community.

KAI: There’s a huge neighborhood brawl -- whites against blacks. And in the middle of this melee, the guy who runs the white grocery store gets beat up. Well, that’s one indignity too many for him. He wants revenge. So he leaves the fight...

PAULA: Goes to the police, goes to the sheriff and says in fact that black people are in a conspiracy to kill white people.

KAI: And he says the People’s Grocery is at the center of this conspiracy. So the cops freak out. They deputize a bunch of white men and form a mob. And in the middle of the night, they raid the grocery store.

PAULA: But what they don’t know is that the black community, and particularly men of the People’s Grocery, assume that this is going to happen. And they lay in wait for these men to come, and there's a shootout. Three of the deputised men white men are gravely injured.

KAI: The cops eventually arrest the men of the People’s Grocery -- Thomas Moss, Calvin McDowell, and William Stuart -- and they throw them in the county jail.

Now, nobody’s confused about the danger these men face. So at first, an armed, black paramilitary group stands guard outside that jail. But then, the injured white guys didn’t die. So, it seemed like things were gonna cool down. The black group outside the jail took their guns and went home.

PAULA: The very next night, 75 masked whites on horseback come to the jail, take them to an abandoned railway yard, torture, and lynch them. It’s true eye for an eye vengeance.

KAI: The torture is meant to mirror the deputies’ injuries. One man is shot through the eye. Another through the cheek. Calvin McDowell fights back, so they shoot off his fingers, one by one.

PAULA: And so here we have this young man, who is emblematic of the rise of the South. Who is a hard worker, who is not even particularly political by the way, but who's just standing ground to try to preserve what he had earned. And he is lynched. And this makes Wells begin to begin to see things differently and to have different ideas about what's really going on. And she's one of the first to really begin to put certain elements together.

KAI: Coming up, the truly revolutionary ideas of Ida Wells -- and why so many of us don’t realize they came from her.

[BREAK]

KAI: This episode is really a follow up to one we made at the start of this season. It was a story about a black family in the Mississippi Delta. They’ve owned a tract of land for generations -- for so long that nobody alive knows how they got it in the first place.

VERNITA BLOCKER: We were surrounded by people who did not own land. They lived on someone else's land. They lived in someone else's house. And it was just always drilled into me, as long as you have breath in your body to just hold onto the land. Don't ever sell it.

KAI: I traced the land back to the end of Reconstruction, to the same moment in which Ida Wells was developing her political ideas. The land told a far broader story about that first generation of black Americans after Emancipation, and the struggle to create a truly multiracial society in the United States. To hear that episode, text “land” to 70101 and we’ll send it right to your phone. Check it out.

[END OF BREAK]

[Outdoor sounds at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice]

BRYAN STEVENSON: You know the people who carried out this violence, you know they could have buried the bodies in the ground. [Fades out]

KAI: Back in Montgomery, at the lynching memorial, Bryan Stevenson leads me out of his haunting forest of hanging monuments.

BRYAN: But they didn't want to do that. They actually wanted to lift up this violence, because they wanted this violence to not just victimize the individuals who were murdered. They wanted it to victimize all African Americans. They wanted to taunt and torment and terrorize every person of color, every black person in the community. And to do that, you had to lift it up. You had to let the bodies be seen by everyone.

KAI: He’s leading me to a grove of trees that they’ve named after Ida Wells. It’s where they ask visitors to sit and contemplate her message.

BRYAN: She shamed America. She said this is our national shame. She said it's not just the lynchers, it's the rest of you who stand silent, that have created this phenomenon. And in many ways she did more than document lynchings, she created an understanding about the greater threat that this terrorism represented.

KAI: The People’s Grocery lynching changed Ida, personally and politically. She was galled, but she was also driven to act, in ways that would help define the next century of American life. The white newspapers that were present at the lynching -- gleefully chronicling it -- they reported Thomas Moss’s last words.

PAULA GIDDINGS: His dying words were tell my people to go West. There is no justice for them here.

KAI: So Ida campaigns for just that: Get out of here; it’s not safe. That’s what she writes. She even publishes investigative reports on life in Oklahoma. Because she wants to assure black migrants it’s safe to go there. And people do.

PAULA: And in a very short time blacks begin -- somewhat dead even to Ida Wells’s surprise -- they begin to pack up and go to Oklahoma. Eventually more than 20 percent the black population will leave Memphis within a very short amount of time.

KAI: This event is now considered one of the first big waves in the Great Migration: A massive, decades-long movement of black people from the South, to the North and the West. It shaped just about every big city we live in today, and Ida Wells helped set in motion.

She’s also one of the first people to understand the power of organizing black workers. Here’s how she explains it in one of her most famous pamphlets, called Southern Horrors.

ACTOR: If labor is withdrawn, capital will not remain. The Afro-American is thus the backbone of the South. The white man's dollar is his god.

KAI: She wrote this stuff in 1892! And there’s more. Sixty years before Martin Luther King led a bus boycott in Montgomery, Ida came up with the idea in Memphis. She said, listen black folks, until they prosecute somebody for these murders, don’t ride the trolleys. Boycott ‘em. And it just about put the trolleys out of business!

PAULA: And so she takes valuable lessons out of that. One lesson she learned is, she said, you know, we need not respectability as much as we need civil disobedience. And civil disobedience -- not just the elites. You know, before her, the idea of race relations were that black elites and white elites would negotiate and come up with something. She said, this obviously isn't working. She said, what the South depends on is black labor and Northern capital. So if we affect black labor, if black labor can rise up in a unified way, then we can have a tremendous impact on freedom and on and on civil rights, particularly here in the South.

KAI: But here’s the thing: People hated her for saying this stuff. And not just white people. Black people, particularly black men, really struggled to hear what Ida Wells had to say. I mean, all this stuff about protest and doing it alongside poor people at risk of losing everything -- that was enough. But then, she crossed a real, bright line.

Even before the People’s Grocery murders, Ida had begun investigating lynchings, all over the South.

ACTOR: Eight Negroes lynched since last issue of the Free Speech, one at Little Rock, Arkansas.

KAI: She’d check out the story whites told about each case, and she’d publish her findings.

ACTOR: Last Saturday morning, where the citizens broke into the penitentiary and got their man; three near Anniston, Alabama, one near New Orleans; and three at Clarksville, Georgia.

KAI: And as she studied this terrorism, she realized its real purpose was to erase inconvenient truths. Ida Wells’s investigative reporting uncovered a pattern: White people kept accusing black men of rape. But when she probed, she always found something quite different: consensual, interracial sex.

ACTOR: Nobody in this section of the country believes the old threadbare lie that Negro men rape white women. If Southern white men are not careful, they will overreach themselves and public sentiment will have a reaction; a conclusion will then be reached which will be very damaging to the moral reputation of their women.

KAI: These are the words that almost got her killed. A mob burned down her newspaper office, and she was forced out of Tennessee. She eventually landed in Chicago, where she spent decades writing and organizing black political power. She even ran for office. But she never, ever let go of this point about sex -- and a lot of people never forgave her for that. Because it didn’t just anger segregationists, it also really got in the way of what liberal white women were trying to argue for themselves at the time.

PAULA: This is also a period of time, Kai, when white women are trying to get into the public sphere as well. And because of the cult of true womanhood, the only way that they can justify going into the public sphere is their moral superiority. If this is being undermined by Wells, which it is, it's also undermining their rationales.

KAI: Liberal white women called her a liar. They tried to keep her out of the suffrage movement. One leading white feminist even claimed that Ida Wells was mentally ill.

Ida would spend the rest of her career isolated from her peers, both within the movement for women’s rights and the one for black rights. She struggled to finance her work and her life, because she insisted on telling the whole truth.

PAULA: She is talking so plainly about sexuality and about rape. Nobody even mentions the word rape. You know, they would use all kinds of metaphors for rape. You know, someone was “outraged.” But not use the actual word for rape. And Ida says, Rape!

PAULA: She said, if you want to talk about rape, let's talk about what's happened in slavery and what continues now of the rape of African American women.

KAI: All of this made her “difficult,” as they say. And it’s one of the main reasons we’re only now, more than a century later, really coming to appreciate the role she played in American history. As early as the 1890s, Ida Wells was calling for a national, professional civil rights group. And for a federal law to protect black people from terrorist violence.

KAI: Two ideas that nobody was talking about, that she was decades ahead...

PAULA: That's right. That's right.

KAI: ...on saying it needed to exist.

PAULA: You know, Kai I think you can make a credible case that Ida Wells's anti-lynching campaign is really the beginning of the modern civil rights movement.

KAI: And for that, she has now got a Pulitzer Prize. Maybe the Nobel people oughta take note. But maybe the rest of us should, too. You know, there’s that meme, “Listen to black women.” Well, we’d have all been better off if folks had listened to Ida Wells sooner.

CREDITS

KAI: The United States of Anxiety is a production of WNYC Studios

This episode was reported and produced by me. A special thanks to Paula Giddings, who to my mind deserves a Pulitzer as well. Do check out her excellent biography, IDA: A Sword Among Lions

The episode was edited by Karen Frillman, who is also our executive producer

It was mixed by Isaac Jones.

Our team also includes Emily Botien, Jenny Casas, Marianne McCune, Christopher Werth, and Veralyn Williams.

With help this week from Michelle Harris and Kim Nowaki.

Our theme music was written by Hannis Brown and performed by the Outer Borough Brass Band.

Do keep in touch. You can follow me twitter at kai_wright.

Thanks for listening, and take care of yourselves.