Let the People Decide

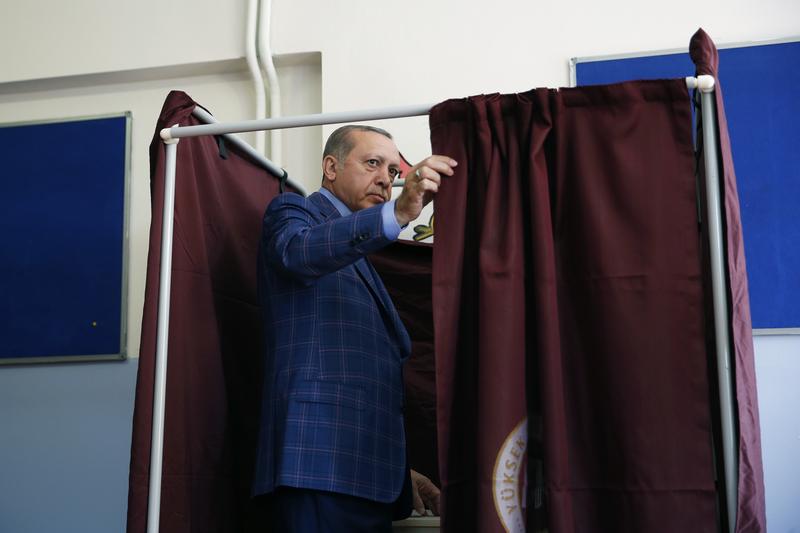

( AP Images )

BOB GARFIELD: This is On the Media. I'm Bob Garfield.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And I'm Brooke Gladstone. Last weekend, we heard about a referendum in Turkey in which, according to the government, a slim majority voted to change its democracy.

[CLIP]:

MALE CORRESPONDENT: Turkey’s President Erdoğan narrowly wins the referendum which will vastly increase his powers. He says constitutional changes will now go ahead.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Actually, the past year has been chockablock with examples of the public weighing in on fundamental questions related to governance and justice and even national identity, ranging from a peace deal in Colombia to Brexit, to a newly-proposed constitution in Thailand, to a vote in Hungary on migrant quotas. In fact, the word “referendum” is very much in vogue, meaning everything from a binding vote to a nonbinding opinion poll, to a harbinger of how the public feels about Trump, based on the results of a local election, like in the vote this week in a conservative district of Georgia which saw Democrat Jon Ossoff come in first among 18 candidates.

[CLIP]:

MALE CORRESPONDENT: This election tomorrow is a referendum on President Trump.

[END CLIP]

BROOKE GLADSTONE: The vote resulted in a runoff but the press had already decided – it was a referendum, metaphorically, Meanwhile, real referendums increasingly are held on issues large and small and the pundits can't decide if that's a good thing or not.

Matt Qvortrup is a professor of applied political science and international relations at Coventry University in the UK. He’s also the author of the book, Referendums and Ethnic Conflict, and editor of an essay collection on referendums around the world. Matt, thank you for joining us.

MATT QVORTRUP: You’re welcome.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So, what’s a referendum?

MATT QVORTRUP: A referendum is basically when politicians ask the people for their opinion or, in other circumstances, when the people demand to have a say on a law or a policy.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You gather enough names on a petition.

MATT QVORTRUP: Petitions, yes. Berlusconi, the former prime minister of Italy, was actually ousted after a referendum. He passed a law that said that the head of state could not go to court; he had immunity from prosecution. Then the people of Italy, you know, 500,000 of them, gathered the required signatures, and then there was a referendum on that law; 95% of the people voted for the repeal. And, as a result of that intervention by the people, Mr. Berlusconi was ousted. So you can have quite dramatic consequences of having the right to call a referendum.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Does a referendum have to be binding?

MATT QVORTRUP: Well, referendums tend to be binding. Then in some countries, for example, my own country, Britain, where we don’t even have a constitution because we like to be a little bit odd, they’re always unbinding. But the politicians don't really dare to go against the will of the people so, therefore, in practice it’s always binding. If you sort of want to be political sciency about it, it’s often the case that you make a distinction between a plebiscite and a referendum, In general, a plebiscite is a vote that is held in a dictatorship, So, for example, Hitler would ask people on various policies and then 99.9% would vote yes to it. And he would probably, himself, call it a referendum but among people, the experts, we call that a plebiscite because we know the result is a foregone conclusion.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Mm-hmm. So when were they first held, and what purpose did they serve?

MATT QVORTRUP: The first time it was called a referendum was in the 15th century in Switzerland, in Davos, which is now the place where the rich and famous meet every January. And in that time, it was decided that major decisions by the local council had to be put to a vote because you couldn’t pass legislation that was really, really important without actually making sure that the people were happy with it. Switzerland was probably the only country at that time that was anything approaching a democracy.

But if you want to go back even further, the Romans actually had referendums. So it’s an idea that has been around as long as people have been thinking about democracy.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Now, you’ve written that in Europe they came to prominence as a political tool in the mid-19th century, when monarchies seemed to be losing power. You draw attention to the tumultuous year of 1848 and you quote [LAUGHS] the French politician, Alexandre Auguste Ledru-Rollin who said, there go the people. I must follow them for I am their leader. [LAUGHS]

MATT QVORTRUP: Yes, and that is one of those sort of paradoxical things. You might have thought that he’d had a focus group who had been conducting polling a little bit prematurely.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

The idea at that time was that you don't have power given to you by God. You have to make sure that the people are happy with you. And it’s been in a steady growth ever since.

Now, it’s interesting that at that time or shortly after, a guy who was known to be quite flamboyant, who had very populist policies – he was called Napoleon III, he was a nephew of the real Napoleon, if you like – came to power. And he was seen as a bit of a, a Donald Trump of his age. And he would often follow that particular slogan and then go to the people and make sure that he was loved by the people, in referendums. The problem about Napoleon III’s referendums was that they were hardly fair. In most cases, the ballot paper would just say, oui that is, yes.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

And there wasn’t really much of a choice there. So they’re probably in the category of what we would call plebiscites.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Now, the reason why we’re taking on this issue is because the perception of referendum seems to be undergoing a change, or at least there's a lot of conflict about it. People see them as frequently a tool ostensibly designed to take the pulse of the people but really used to erode democracy and strengthen the power of demagogues and dictators. We saw some of this argument going back to the 20th century, after Hitler essentially gave [LAUGHS] the referendum a bad name.

MATT QVORTRUP: Well, Hitler held, I think, altogether four referendums. One of the referendums was whether to have unification between Germany and Austria and, predictably, he won by 99% of the vote.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Nobody wins by 99% of a vote.

MATT QVORTRUP: No and, of course, you rig the vote, and they had a bit of a surplus of votes, it turned out, because they had printed the ballot papers beforehand.

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

And people who were in concentration camps were also forced to vote for Hitler, and we have meticulous details about how they engineered these votes. Those fake referendums, or plebiscites, rather, were hardly fair at all.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You have those sorts of referenda all through the ‘70s. Khadafy held then, Castro, Augusto Pinochet held one in 1978.

MATT QVORTRUP: Also, nowadays, Saddam Hussein, two months before he was ousted by the coalition, had a referendum on some policy changes in Iraq, and he won by 100%. So 100% of the Sunnis, the Shias, the Kurds all voted for Saddam Hussein, officially. So I think in a dictatorship, a plebiscite is not really about finding out what people think, it's more about sending a signal that you are able to completely control the process and everybody will turn out to vote. And then people will sort of jump from that to saying, well, therefore, referendums must be a bad idea.

But I think it’s important we make the distinction between plebiscites and referendums because in countries that are moderately demographic, even, or countries that are fully democratic, they can sometimes backfire. So in the 1980s, when the power of Pinochet had been loosened –

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Augusto Pinochet, the dictator of Chile.

MATT QVORTRUP: Yes. He actually lost a referendum because he didn't bother to rig the vote sufficiently well.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: And, and you have a great example of Charles de Gaulle in 1969. [LAUGHS]

MATT QVORTRUP: Yes, Charles de Gaulle is one of my favorite examples, where he campaigned on the slogan, “Me or Chaos.” And the French overwhelmingly voted for chaos –

[BROOKE LAUGHS]

- which, of course, didn’t happen. He wanted to abolish pretty much the Senate, which was a rather draconian measure.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So clearly, sometimes the seemingly most democratic of tools is used to erode democracy, but not always.

MATT QVORTRUP: No, and I think also when we talk about eroding democracy, I mean, we still have presidential elections. The fact that Stalin and Mussolini had presidential elections that were rigged does not mean that we are now against representative democracy. At some level, you could say, well, Erdoğan was not actually strengthened by this referendum.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: The president of Turkey.

MATT QVORTRUP: Yes. He could have forced this through without a referendum, just saying, you know, I’m the elected president, I’m with the people. And, in this case, he held a referendum. It turns out now that he does not have a majority in the capital, he doesn’t have a majority in the largest city, Istanbul. And, therefore, what was supposed to be a vote by acclamation that would show what a strong leader he was, he is now weak.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: So what are the conditions in which referendums work the way they are supposed to?

MATT QVORTRUP: Well, what is important in a referendum is that the people are given the opportunity to actually debate the issue. California is a wonderful example. Now, you sometimes had issues on the ballot in California where people have debated the pros and the cons and have come to a sensible conclusion about that. Last election, there was a referendum on the death penalty.

In Britain, in the Brexit referendum, people arguably knew what they were voting for. Obviously, people don’t become experts, sort of walking, talking encyclopedias of political economy and law, and so on. But the voters in Britain were firmly as well informed as they would be in a parliamentary election.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: There was a lot of commentary after the Brexit vote that British voters are systematically ignorant. But you’ve suggested that in cases where liberalism won out, for instance, the vote on legalizing gay marriage in Ireland in 2015 or when a majority of Hungarians boycotted Viktor Orban's anti-immigrant referendum in October, rendering the results void, that the commentators don't come out and decry those referendums.

MATT QVORTRUP: In Britain, in particular, much of the liberal media were saying, well, the people couldn't possibly have an opinion about Brexit, and the same media felt that the so-called “recently ignorant people” were incredibly enlightened when they voted against Scottish independence. So there is an element of wanting the rules that suit your political philosophy, which is probably a natural thing.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: The question is, fundamentally, do referendums hurt democracy or do they merely reflect the democracy that they’re held in?

MATT QVORTRUP: I think, to a degree, they reflect the democracy they’re held in, but I actually think they strengthen democracy. It’s fundamental in politics that you are divided into camps but referendums allow people to support one particular party and then disagree with them on certain other issues. Referendums allow for different constellations of politics.

What we’ve seen in this country was that a lot of people were not great fans of David Cameron, the conservative prime minister we used to have, but a lot of people who were of a different philosophical persuasion agreed with him on Europe and, therefore, suddenly realized that he probably wasn't such a bad person, after all. So what would appear to be a very polarizing issue actually allowed people to team up with people they normally would be opposed to. Democracy is a system that thrives on disgruntled people.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: You call this institutionalized grumpiness?

MATT QVORTRUP: Yes, and I think institutionalized grumpiness is a wonderful thing. Democracy is very much about holding politicians to account, and if they fear that if they don’t do a really good job the people will vote them down, well, then that’s a good thing. But in order for that to happen, we shouldn’t deplete people’s civic reserves. And, for that reason, we should probably limit referendums to the really important issues, where they can come out and show their disgruntledness.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Matt, thank you very much for joining us.

MATT QVORTRUP: You’re welcome.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Matt Qvortrup is professor of applied political science and international relations at Coventry University in the UK. He’s also the author of the book, Referendums and Ethnic Conflict, and editor of an essay collection called Referendums Around the World.

[MUSIC/MUSIC UP & UNDER]

BOB GARFIELD: That's it for this week’s show. On the Media is produced by Meara Sharma, Alana Casanova-Burgess, Jesse Brenneman and Micah Loewinger. We had more help from Sara Qari, Leah Feder and Kate Bakhtiyarova. And our show was edited – by Brooke. Our technical director is Jennifer Munson. Our engineers this week were Terence Bernardo and Sam Bair.

BROOKE GLADSTONE: Katya Rogers is our executive producer. Jim Schacter is WNYC’s vice-president for news. Bassist composer Ben Allison wrote our theme. On the Media is a production of WNYC Studios. I’m Brooke Gladstone.

BOB GARFIELD: And I’m Bob Garfield.