Lessons From a Year in Isolation

( Niky Crawford )

Kai Wright: This is the United States of Anxiety - a show about the unfinished business of our history and its grip on our future.

Cash Jordan: As of now, indoor dining has been shut again.

Marcia Kramer: Officials took what seemed like another step backwards in the war against COVID-19, another sign that the second wave is upon us.

Gov. Andrew Cuomo: My advice is be careful. You are not imprisoned in your home. (laughs)

Dr. Kathleen Smith: We're humans. We're social creatures. We need each other to survive and to thrive.

[Pots and pans banging, shouting]

Dan Harris: We had a big loneliness problem in this country before COVID-19. Social distancing has put it on steroids.

Lucie Langford: As somebody with a mental illness, sometimes my house isn't the safest place for me. Sometimes I really do need to get out.

Noah Witenoff: When you live alone, when you say a household and you're the household, the thought of not being with other people for an indefinite amount of time, is overwhelming.

[music]

Kai Wright: Welcome to the show and happy holidays, everybody. I'm Kai Wright. This week, I want to start by just introducing you to somebody I, met who turned out to be kind of a kindred spirit.

Adiva Kaisary: Can you hear me?

Kai Wright: Yes, I can hear you. Can you hear me?

Adiva Kaisary: Hi. My name is Adiva.

Kai Wright: This is Adiva Kaisary who is a 13-year-old eighth-grader who lives in Queens. She's the first of a few people you're going to meet during this show, which is going to be a reflection on the year we've all been through, a reflection about our efforts to connect with one another in trying times, and a reflection with history in mind too, but I'll get to that in a bit. For now, the point is, we're not live, we're not taking calls this week. We just want to introduce you to some people in our community, starting with Adiva. Adiva, what's the thing you're most looking forward to in the new year, in 2021?

Adiva Kaisary: First off, I want this to end. I want everything to go back to normal. I want to go to school like a normal person, hang out with my friends again, and I just don't want to stay home. I'm so sick of staying home all day.

Kai Wright: Adiva, for you, this year, it has been especially hard, I imagine, because you just moved to New York in Queens from Bangladesh, right?

Adiva Kaisary: It hasn't even been two years, yes.

Kai Wright: When this pandemic hit, you were really just getting settled in. What was that like?

Adiva Kaisary: When I first came, I didn't have a lot of friends. When I did make some, the people that I had, I used to try to cherish those people. Back in the day, you don't get to go a lot of places by yourself. We would go to McDonald's, get food. We would just go to the park before school, and even after school, we would go over each other's houses and stuff like that, goof around and just have fun.

Kai Wright: What was it like having to be stuck at home all of a sudden?

Adiva Kaisary: There was a specific friend that I had since sixth grade, they were one of my first ever friends to actually stick with me. Me and her were really close, and after the lockdown, I was just very down, and I didn't even feel like talking to anybody else. Every time she would call, most of the times I wouldn't answer because either I was tired or just wasn't really in the mood to talk to anybody.

Kai Wright: Because you just wanted to shut down.

Adiva Kaisary: Exactly.

Kai Wright: I know what that feels like, to be honest. I've had a few experiences where it's like, I love my friends and I miss my friends, but at the same time, I don't know, there's something about all the technology of it that also feels like I don't want to be bothered.

Adiva: Exactly. Every time someone texts me now, I don't feel the excitement like I used to. Whenever I would see a text, it's like, "Oh, they texted me. Okay. Cool." I don't really feel like talking to anybody. I wasn't talking to her at all, for months. Just one day she texted me. She was like, "Hey, you haven't been talking to me. I don't know what happened to you, but if you're going to act this way, then I'm not going to be friends with you for very long."

I was like, "There's a lot of things going on, it's just stressful. I can't always talk to everyone." She's like, "I get that, but you should show some effort." I was like, "I'm trying to." She was like, "No, I can't be friends with you like that. It's hard." I was like, "All right." I basically lost her.

Kai: Oh, wow. In the course of this pandemic?

Adiva: Yes.

Kai: Oh, I'm sorry. That sucks.

Adiva: Yes. I usually don't talk about how I feel and stuff like that. I like to keep it bottled up inside. I feel like not everyone understands. It's like, I understand the best. I'm just keep it to myself.

Kai: Did you have anything that you experienced in those months that you look back and wish you had talked to somebody about, that you'd wish you'd been able to share with one of your friends?

Adiva: To be honest, yes. I'm just stressed. I want to take everything out and just tell somebody, and maybe they'll relate to me because they're in the same position I am.

Kai: Because maybe they were having the same process.

Adiva: Exactly.

Kai: When you imagined 2021, and you said getting back to normal as you- just sort of your wildest dreams of what it's going to be like.

Adiva: Probably go somewhere, just have fun or go somewhere far. I don't know. Just anywhere outside of my house.

Kai: [laughs] Far could be down the block, right?

Adiva: At least it's outside of my house.

Kai: I hear you.

Adiva: Maybe like the beach or somewhere, I don't know.

Kai: This a real grown folks thing, but I can't wait to be sitting at brunch on a Saturday afternoon, five or six of my friends there and we're all wearing like short shorts and tank tops and we're just laughing about stupid things. That's what I picture.

Adiva: Yes. I would say maybe go over a friend's house with five or six of my friends and just hang out, watch movies or something, sing, maybe play volleyball or something.

Kai: I want to do that, too. Before we let you go, is there anything you want to say to all those New Yorkers out there listening right now?

Adiva: Go easy on the kids. It's really stressful. It's really stressful. People think that we're having fun because we're home and stuff like that, but it's really not.

Kai: I hear that. I hear that. Go easy on the adults, too.

Adiva: Oh, yes.

Kai: Go easy on all of us. We're all having a hard time.

Adiva: True.

Kai: That was 13-year old, Adiva Kaisary. As I said, she's one of a few people you're going to meet during this show who will just reflect on this really challenging year. This is our final show of 2020. While we're always focused here on the collective choices we face as a society, we also try to keep in mind that we're all individual human beings, each trying our best, hopefully, our best, to live together in love and enjoy. That's been harder this year than most, but for some of us, the challenges of this year have also been transformative. We're going to hear a couple of personal journeys, stories like Adiva's, that are about human connection. We are still thinking about history as we do this.

These stories will be our show's contribution to a 10-year time capsule that WNYC is making. The station is going to open that capsule in 2030, whoever is here then, and we'll see what our 2020 selves had to say about this remarkable year. More about that time capsule later in the show. We're going to take a short break. When we come back, our next reflection on this crazy year. I'm Kai Wright and this is The United States of Anxiety.

[break]

Welcome back. This is The United States of Anxiety. I'm Kai Wright. This week we're helping to build a 10-year time capsule that WNYC is creating. You might recall that right before the election, we did our own little mini time capsule on this show, but now our whole station is participating, as well as listeners. For our own contribution, we're thinking about human connection, how hard it's been to maintain, where we found it, and what it's meant.

We're introducing you to a few people who are sharing their own stories of connection during the pandemic. We're not live this week. We're not taking calls or anything. I just want to invite you to hear these personal stories. At the end, I'll tell you how to add your own submission to the time capsule. Our senior producer, Veralyn Williams, goes first.

Veralyn Williams: Hey, guy?

Kai: Hey, Veralyn.

Veralyn: As you know, I moved back to the Bronx this year, officially March 1st, into an apartment that I love. Thank God, because I've now spent months there working, thinking, laughing, exercising, all alone.

Kai: All alone.

Veralyn: Technically, I also fell in love, but that's a story for another day. [laughs]

Kai: That's' good to say. I don't think you're alone, as far as I know, but anyway.

Veralyn: I've also spent a lot of time checking in with family and friends, many of who are dealing with COVID and what it is doing to our city. Anytime I got a phone call that wasn't scheduled, my heart sank, because I knew that anything could be waiting for me on the other side of picking up. There was this one conversation with one of my friends at the station, Cindy Rodriguez.

Cindy Rodriguez: Can you hear me?

Veralyn: Yes, I can hear you. She's a reporter at WNYC.

Cindy: Okay, that's going to work.

[background conversation]

Veralyn: I've known her since I was a teenager, she's always been super supportive. Cindy shared with me she was having a really hard time. She, uncharacteristically, because most reporters, they don't believe in being the story, she decided to share this time.

Cindy: I got tested over the weekend because I thought that I would test negative, and I didn't, I tested positive. Kai,

Veralyn: Kai, what she needs to know, when Cindy and I spoke, this was back in May, she had already been experiencing COVID symptoms for two months, and she was really sick. Like a lot of people, just had to assume she had it.

Kai: As I remember, back then it was still really hard to get a test.

Veralyn: Exactly. Cindy had hoped the virus had already run its course.

Cindy: It was really hard for me to hear that, but then I spoke to my doctor, and she said that you need to trust me that you are not going to die from this, and you need to trust me that you're not going to get really sick.

Kai: Does Cindy have any idea how or where she got COVID-19?

Veralyn: It's impossible to really know. When the virus started to spread in New York City back in March, Cindy was reporting in nursing homes, which were especially hit hard by COVID-19, a devastating amount of people died. It wasn't long after that that Cindy woke up wheezing and feeling extremely sick.

Cindy: I really did not think that I had the virus, I just thought I had a regular run-of-the-mill cold.

Veralyn: Then, she described her symptoms to her doctor.

Cindy: I told her I had a really bad headache, and that I had like a little bit of feeling of asthma. She said, "You have the virus and you need to stay home and you can't leave until your symptoms go away. I also had a lot of chills. Then, that was really, really hard for me to hear. It was also hard for me to hear that I couldn't get tested and that there was nothing she could prescribe for me.

I asked her if she could give me Plaquenil, which was this medication for autoimmune diseases that was supposed to be working. She said, "No, I can't. That's for people that are really sick and in the hospital." Then slowly, I started to get sicker, and my congestion got much worse. My head felt like it was going to explode. I could not get warm, and I'd lost my smell and my taste. She said, "All you can do is wait."

Veralyn: Cindy, like me, lives in an apartment all by herself. Actually, a lot of New Yorkers do, something like a million people live alone in the city. A vast majority of us are women.

Cindy: It's really a hard moment for people that are living alone. It's a hard moment for everybody, but living alone, you have to really take care of yourself.

Veralyn: I don't know how this is hitting you, Kai, but for me, after a summer of a few socially distant picnics, and I had a small birthday celebration where I got to hug a friend I hadn't seen in months, it feels hard to emotionally connect with just how many unknowns there were in March. Staying away from anyone you didn't already live with felt like the only way to stay safe and to keep the people you love safe.

Kai: Right. We just had to make our lives so small and stop seeing people. I was here with my partner and I felt lucky. As a consequence, at least I had somebody around.

Veralyn: The truth is, Kai, so many of us were not well going into any of this.

Kai: That's the truth.

Veralyn: On top of dealing with COVID, Cindy has also been living with anxiety for almost a decade.

Cindy: I knew that my anxiety was going to be through the roof. My doctor, she offered me an inhaler. I said, "Sure." Then, I asked her for Xanax and she said, "Sure." I struggled with anxiety.

Veralyn: It started with a really shocking experience.

Cindy: I guess a few years ago, probably...

Veralyn: Six years ago, Cindy started to have a strange tightness in her throat.

Cindy: It almost felt like I was like the ball that you get in your throat before you're going to cry.

Veralyn: It really bothered her and she assumed it was something physical.

Cindy: I went to a bunch of different doctors, I went to an ENT doctor. I went to this specialist that deals with voice issues. Then, finally, I went to a neurologist. The neurologist put me through all of these tests.

Veralyn: She told me the test involved sensors that were put all over her body. They're really painful tests, in order to measure whatever messages her muscles were sending to her brain.

Cindy: He called me and said, "Come in for the results," but he was like, "You need to bring somebody," and that felt very strange to me. I was like, "Okay." My girlfriend at the time, my partner at the time went with me, and he brought us into his office, and he sat us down. We both were like, "What's happening here?" He said, "I'm sorry to tell you, but you have Lou Gehrig's disease." My partner didn't quite know what Lou Gehrig's disease was. He told her what it was.

Veralyn: Lou Gehrig's, affects the nervous system, it's also known as ALS.

Cindy: He said that it's a disease that moves quickly and that it was probably going to kill me. She broke down and was sobbing hysterically. She really could not hold it together and she was really distraught. I looked at him and said, "I don't believe that." I was in disbelief.

Veralyn: She couldn't believe it. Yet, she was destroyed by it.

Cindy: I remember I called my sister from there. I told her, and we both just started sobbing.

Veralyn: Cindy went on a search for other neurologists. She saw two other doctors that ran the same tests and got very different results.

Cindy: They both said to me that I do not have ALS. One of them was very clear like, "You do not have to worry, it was a mistake, it was misdiagnosed. You can live your life and know that you're fine." The other one was like, "It looks fine to me, it looks like you're fine, but you never know." That "you never know" just stayed with me for so long.

Veralyn: For instance, one of the first signs of ALS is weakness in your muscles, weakness in your legs, your hands, your tongue.

Cindy: Everything became a test of those things. I was constantly looking at my tongue. I was walking on my toes to make sure that I could. When I'd go to the gym and lift weights, I was like, "Why can I only lift 15 pounds today, and yesterday it was 20?"

Veralyn: This misdiagnosis, this death sentence, essentially, took such a toll, and getting COVID just brought it all back.

Cindy: That was the beginning of this distrust in my body and my health. It's similar now. It's that same, "What I have this and what is it going to do to me and can I trust that my body is really going to be okay." On April the third, I see that I wrote to her.

Veralyn: When we were talking, Cindy pulled up all these messages between her and her doctor during this time. I asked her to read through some of them.

Cindy: I'm feeling so much better. Yesterday, things started to turn around. By the evening, I was feeling stronger, my appetite had come back. It feels like I have the final bits of a normal cold. Then, I said, "Thank you so much for your caring concern. You and your staff are so brave for exposing yourselves to people who caught this and who are really sick and suffering. Crossing my fingers, this doesn't get as bad as predicted and we can hug each other again one day soon."

Then she said, "Thank you, I'll take you up on that hug when we can. I'm normally not overly huggy, but this might have changed that, you don't realize how much you miss human contact until it's sharply curtailed. I'm thrilled you're improving brace for a possible backward step, but anticipate continued overall improvement."

Three days later, it was like the backslide came. I have chills again, and I've lost my smell and taste again. I can't get rid of the head congestion. Then, April 10th, I can't believe how many times I've bothered this poor woman. Then I wrote, "Congestion is worse on the 11th, breathing is getting harder, feels more than anxiety. Anxiety is adding to it." Then I saw her, and she offered to give me an antibiotic called Zithromax, because she was like, "It seems to be working on some people. Maybe you have an underlying bacterial infection." I remember that day because the second she told me she was going to prescribe me something, I felt so much better. The difficulty breathing suddenly went away. It was just like it's the idea that, "Oh, you can actually treat this. I could actually get better."Of course, the Zithromax did not do anything. It was like a placebo effect that lasted for a couple of days.

Veralyn: So many of us want edge at the beginning of this pandemic. Hospitals were turning sick patients away. We were seeing footage of refrigerated trucks for the people that we lost. We were all worrying about everything, but Cindy and her doctor already knew anxiety was a problem for her.

Cindy: I asked her if maybe I should take Lexapro, which is like a mood stabilizer that my sister was taking to see if that helped, and she gave it to me and that really had a really bad effect on me. It threw me into this panic. I couldn't lay down because I was dizzy and I was super nauseous. My vision went blurry, so I couldn't see my phone. It was pretty awful.

I called my sister, like, "God, I don't even remember any more at night or two in the morning." She stayed on the phone with me from two in the morning until three o'clock the next day.

Then I was able to get the doctor to call in. She was saying to me, "You have to get up off the floor and you have to get to the Xanax and you have to take a Xanax and you have to pass out and end this." Finally, I did and I passed out. I woke up, I don't know how many hours later on my floor.

Kai: Man, that is so hard to hear. That is to such an intense experience. So many people had these kinds of crazy experiences this year.

Veralyn: Yes. As I listened to Cindy, both of us sitting in our apartments alone, staring at each other through Zoom, I saw her as expected, really struggling to remember. We call the person she called at the time.

Cindy: Veralyn, this is my sister, Lenny. Lenny, this is Veralyn. Sorry, you guys have-

Lenny: Hi.

Cindy: -to meet in this distant way, but at least you can see each other.

Lenny: [laughs]

Veralyn: Yes.

Lenny: How are you?

Veralyn: I'm well, I love your sister very much. [laughs]

Lenny: We do, too.

[laughter]

Cindy: Lenny, as you know, you ended up being on the phone with me a long time. Can you just describe what you remember from that night?

Lenny: Yes, I remember you preparing me. We were talking on the phone earlier in that evening. You had said that you were having a lot of anxiety and you prepared me that you might need me in the middle of the night and I said, "Okay, I'm going to sleep with my phone by the bed and I'll keep my ringer on. You just call me for whatever you need." About two o'clock in the morning, you called, and you were not yourself, clearly panicked, clearly panicked that something terrible was going to happen to you.

When people say someone is out of their mind, it really just sounds like such an exaggeration, but you really were out of your mind. I mean that in the sense of, that was not who you were. I could tell when I talked to you, I was just trying to keep you calm and focused and focused on the fact that you could breathe and that you were okay. Let's just check things off the box. I remember trying to walk you through and checking boxes off so I could focus you on each of those things.

We talked about, you were afraid that you couldn't breathe, and I said, "If something happens, I can call 911." You were worried about me calling 911. I said, "I have your address." I repeated your address to you. I said I've looked at the police precinct. I have that phone number. I felt like if I could get you through the night, the sunlight, the daylight was going to give you at least a little bit different perspective, because I always think nighttime, when you're sick or you're troubled, you just feel so much more alone at night.

I felt like if I could just get you to daylight, that you would be a little bit better. I could reason with you a little bit more. We just kept checking off these boxes of the things that were safety nets for you so I could work through the night on making you feel better.

Cindy: My God, that must have been so horrible and stressful for you to hear me not being myself and being so far away. It must've put you in a position where you really didn't know whether I should call 911, but you said to me that that wasn't the case that you didn't vacillate. You knew that I shouldn't call 911.

Lenny: I knew you shouldn't call 911 because we did walkthrough, "Can you take a deep breath?" You could take a deep breath. It was just in some instant before you couldn't take a deep breath. That's all you focused on. We walked through all of the things. "Do you have a fever? Can you take a deep breath? Are you coughing? Are you shaky? Are you weak? Did you eat?" We checked off all the boxes, so I knew you were okay. I knew it was really just what was happening with you psychologically, that where the problem was.

Fortunately, you are reasonable about 911 because I said, "Cindy, what is it that you expect them to do for you when they come?" Because we've already talked through that you don't have a fever and you're not coughing and you can breathe. "What is it that you want them to do?" I think that what you wanted was to have someone there to tell you you were okay.

Cindy: Yes, it was messy. It was pretty messy, but I've learned a lot about myself, for sure. I knew that you're dealing with your own family, but I guess I didn't get to be too much.

Lenny: Nope, you are not too much. I'm happy to be there for you and I'm glad that I was able to be there for you. I'm glad that you felt comfortable enough to share just such deep and hard things with me. It's so important to be able to communicate how you're feeling.

Cindy: I appreciate you saying that. I think you're right. I think that this is an experience that taught me that that's important. It's really something I do want to be more open and I do want to be more connected and I do want to be closer. I look forward to that being like a way of making something good out of an experience that was pretty traumatic for me and for so, so many other people.

Kai: Veralyn, we are gathering Cindy's story because, as I said, it's going to be part of the time capsule that we're going to put away until 2030. What do you think Cindy would say about all of this to 2030? What is her concluding thought on this?

Veralyn: I would say Cindy really sees all of this as an opportunity to grow and to finally deal with that intense anxiety she's felt for so long.

Cindy: I need this to be a transformational moment for me, and I hope that it is. I understand how deep this anxiety runs and I understand that I need to fix it. "Fix" is wrong word. I don't think it'll ever get fixed, but I need to understand where it comes from. I need to understand how to deal with it when it surfaces, because it can be pretty torturous.

Veralyn: Part of what Cindy is discovering is how to be alone. I don't mean living alone or even being all alone, because in that incredibly difficult moment, she was able to depend on her sister. What I mean is, being on your own, being able to sit with yourself and face yourself and know and hear your own thoughts. She's been in a couple of relationships that were full of love but just not right for her. For the first time, she's now asking herself what she truly wants.

Cindy: I do want to build a life with someone. I want to live together. I want to have some pretty traditional things. I've been in serious relationships before, but I've never really been able to ask for what I needed. Partly because I didn't know myself well enough to know what I needed, but I also couldn't do it because it made me feel so vulnerable, but it doesn't do anymore. That's one part of it, but then more than that, I think, is just being there for myself and knowing myself better and trusting my instincts and trusting what I'm feeling and really acting on those things and not avoiding them. Yes. The anxiety comes, and then, at times, I can get to this point where I am saying these things to myself, and not just saying them, because anybody can say those things, but I really believe them and know that I'm okay, that it's fine.

Lenny: It makes me so happy to hear you say that. I was thinking when you were talking about the support system in that moment of a peak crisis, you just, in so many ways, have exactly what you needed, even though you live by yourself and all the different reasons why you might feel you’re alone in the story that we tell ourselves. Now the story is, "I am okay."

Cindy: Yes, exactly. It's so true. I've built some strong friendships in the midst of this, including with you. I also know that so many other people are going through something so similar. Really, I'm just trying to remember that I got through something that was really difficult, and that I can really ride these large waves that life throws you.

Kai: This is The United States of Anxiety. I’m Kai Wright. We'll be right back.

Carolyn Adams: Hi, I'm Carolyn Adams, the Associate Producer on The United States of Anxiety. You may have noticed that we've started to include links for companion episodes in the show descriptions, just a few things from our archives that we think make for good follow-ups to what you're listening to, including this episode. Tap the description in your podcast app, or visit our show site at wnyc.org/anxiety, to find links to more episodes that we think you might like.

If you haven't yet checked out An Invitation to Dream, it's another time capsule project we did the week before the presidential election, a shorter one that helped us all imagine about what might come after Election Day. And here we are, so take a listen. We hope you enjoy.

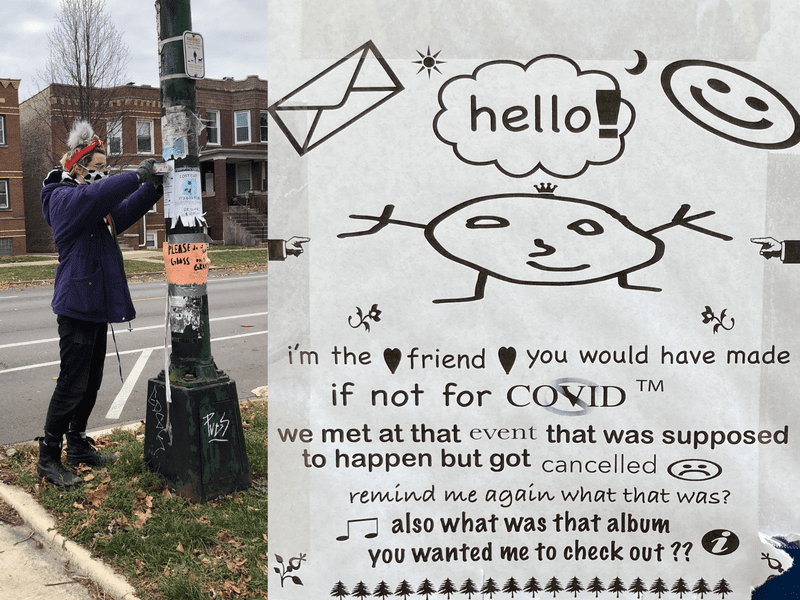

Kai: Our next reflection comes from reporter Jenny Casas, who was out walking in Chicago this fall, when she came across a flyer, an advertisement, Looking for Friends, it was posted by Niky Crawford, who suddenly had a lot of free time this year.

Niky Crawford: My day job was a standardized patient. Do you know what that is?

Jenny Casas: No.

Niky: That is basically a fake sick person for medical students.

Jenny: Back in March when the first COVID-19 cases came to Chicago, Niky Crawford was working this acting job.

Niky: That's a job that requires a lot of people to fly in daily to touch my bare face. When little, old pandemic came, we were like, "Oop, better put a hold on that for a little bit."

Jenny: March turned to April, to May, to June and Niky was furloughed twice. With all that new spare time, Niky picked up some freelancing gigs and got into some new creative projects.

Niky: I started making rugs as a little hobby. I'm trying to think of what I've been doing since July. A little bit of job-hunting, making money, a little bit of making rugs, and then, of course, having conversations with strangers.

Jenny: The pandemic's dripped something essential from Niky's life. I think a lot of us can relate. When I first saw the flyer, I thought it was a call for companionship. Can you just describe that ad for me?

Niky: Sure. An audio tour of this visual flyer.

Jenny: It’s a standard piece of printer paper, black and white.

Niky: This is a black and white printer paper with a little doodle person on there, one circular body with stick limbs and a little crown. [unintelligible 00:35:01]

Jenny: There's a speech bubble that says, "Hello!"

Niky: A lot of other old school emoticons, like fingers pointing at it and flowers and stuff like that. [unintelligible 00:35:10]

Jenny: below that, it says, "I am the friend you would have made if not for COVID."

Niky: We met at that event that was supposed to happen, but got canceled. Remind me what that was, also, what was that album you wanted me to check out?

Jenny: At the bottom, there's tabs cut into the page with a phone number, like any other flyer, advertising a room for rent or a car for sale. Each one says, "How are you?? Text me back."

Niky: I'm using the simulation because I'm better at simulations than I am at making friends.

Jenny: Niky hung dozens of these flyers across a few neighborhoods. The one that I saw was taped under the mouth of a blue USPS mailbox. It just struck me as so earnest. At a time when things are feeling so bleak, here was someone finding a creative way to connect. I texted, and I asked Niky to let me follow along.

Niky: Hi, Jenny. These are little notes that I've recorded either while I was walking and hanging up flyers. One thing I have gotten pretty good at is taping flyers to telephone poles, all by myself. It's really easy to look like an idiot out there. Just walked by a flyer that I already put up, and I saw an older gentlemen carrying groceries on his way home, I guess, and put them down to stop and read the flyer. He didn't take a tab with the number on it, but in a perfect world, maybe he has a really good memory and I will get the best message that I'll ever receive tonight.

Female Speaker 7: Hi, we got your number from the park [unintelligible 00:37:05]

Niky: I got a voicemail. What a voicemail. I think it's just a bunch of teens who found it.

Female Speaker 8: Yes, we found it.

Female Speaker 7: We'd like to say hi.

Niky: One of them is trying to call and maybe as a bit nervous to do it, and they have another who's just making jokes and yelling in the background.

[background conversation]

Niky: The other teen was like-

Female Speaker 7: Sorry, about that, but you're probably a really cool person. We'd like to get to know you.

Female Speaker 8: Your poster is very cute, very adorable.

Female Speaker 7: We love your poster, it’s very--

Female Speaker 8: Thank you. Bye-bye.

Female Speaker 7: Bye. Love you.

Female Speaker 8: Bye-bye.

Jenny: That was the only voicemail that Niky got. The rest are all text messages. The conversations usually fall into one of two camps. Most people respond really genuinely. They give their real names. They tell Niky about real things going on, and they ask a normal niceties. How's your week? How have you been?

Niky: Then the other 30% are like, "We met under the ocean in Costa Rica." I'm like, "Cool, yes. Love the sharks." I'll meet them there, and that's fun.

Jenny: That meeting them there, that theater of humanity, that, more than anything else, turns out to be the thing that Niky was missing.

Niky: The first message I got, I got within an hour of hanging these flyers up, and it's definitely one of the most powerful I've gotten. This is it. This is it, "Dear friends, thank you for texting me. I wasn't sure if we'd manage to get in contact again. It feels like forever since we met at that crawfish eating contest, even though it was this morning. Do you remember? You ate 130 crawfish, which, experts said, was medically impossible. I ate zero because I don't like shellfish. I knew we would be fast acquaintances. I apologize for not using your name. As you recall, we exchanged only code names. Me, Steve, you Big Steve, regardless. I hope this finds you well. Please, listen to Paul Simon's Graceland. Warm regards, 'Steve.'" [laughs]

I was like, "Oh my God, what a powerful message, an hour into this thing."

Jenny: What Niky likes so much about Steve is that they're taking the call from the flyer and just running with it. Improvising fantasy scenarios that match Niky's energy. They go back and forth as these characters for weeks.

Niky: "Dearest, biggest Steve," they write to me. [unintelligible 00:39:36]

Jenny: Together, they build a fake history, teeing each other up for the next imaginary thing.

Niky: To your question, yes, I've made many friends from events that were canceled because of COVID, a little over 20 so far.

Jenny: Braided in there are real questions you would ask your friends. How has your sleep been? How's that project you were telling me about?

Niky: I'm happy to hear that you've made the acquaintance of so many people in these difficult times. If you’re referring to the work project I'm always complaining about, sorry. Progress is tentatively steady. Honestly, creative energies have been in flux this year. I feel pretty optimistic about the new idea for manuscripts. Are you still planning that trip when things calm down?

Jenny: Steve.

Niky: So lovely, so lovely, Steve. Thank you.

Jenny: Genuine interaction always wins out, always.

Niky: Sure, if you want to call this genuine interaction.

Jenny: Niky and Steve's ability to blend the make-believe and the real, it just throws me off, maybe because I, myself, I'm always a little too earnest. I'm a bad liar and that makes me a bad actor. Keeping up this fake reality with Steve or anyone else, it just seems taxing. If I was doing this, I would be like serious inquiries only.

Niky: You would send your friendship contracts to them after a couple of weeks, ask for a couple of references for past friendships.

Jenny: Yes. It's almost as if you are telling someone you have a crush on them, but always reserving the ability to be like, "Just kidding."

[laughter]

Jenny: Hearing you describe it, I'm like--

Niky: That's interesting.

Jenny: You're always ready to be over just playing or like, "Oh, you're really here for this. I will show up with you."

Niky: Cut in what's funny, is if I ever was confessing a crush on someone, I would definitely always have it in my back pocket and be like, "Hey, I got you. Ah, bro, ha-ha, what-if?"

[laughter]

I do hope though, if I ever meet Steve and they see that I'm actually just some fricking bouncy kid who loves to just send smiley faces and goof with people. What if they're like 50 and they're like, "Who the fuck is this?"

[laughter]

I don't know. That's to say, Jenny, 50-year-olds hate me, historically.

Hello? Test.

Jenny: I don't know if you're doing testing, okay.

Niky: Hello? Test, test.

Jenny: Hi?

Niky: Yes, you got me, yes?

Jenny: Yes, that worked.

Niky: Okay, great.

Jenny: Three weeks after that first message from Steve, Niky's inbox was swamped with messages from new people.

Niky: 60, 61, 62, 63, 64. 64. Oh my God.

Jenny: Niky sets aside an hour-ish every day to respond to this growing cast of characters. One person imagines that the two of them met at a strip club. Another person only texts in cat photos, and another person--

Niky: Their first messages were like, "How have you been? I miss your hair, touching it. You can't touch things now." Wow. Out the back, talking about touching my hair. Love it when people touch my hair.

Jenny: Okay. Dina, do you want to give me a little intro?

Dina: Yes. My name is Dina.

Jenny: Dina was the one sending those flirtatious texts.

Dina: They realize we're very similar in the way we interact with people. We love attention. We love being flirty.

Jenny: When it's not the pandemic, Dina is usually a server, and just like Niky, she has a job that's been on hold and can't be done from home. She answered the flyer because she could already imagine the person on the other end being her friend.

Dina: Also, there was no risk either, because if I had met someone from real life-- Anytime I meet someone new in real life right now, it just feels like a risk. I just constantly think about it. Yes. It just felt very natural. It was like these little moments when we would be texting where I felt like we're not stuck in the middle of this terrible, terrible thing that's happening to all of us.

Jenny: Nothing is forever. Steve, the one who met Niky at the crawfish eating contest stopped texting after about five weeks. Niky, after connecting with almost 100 people is ready for something else.

Niky: I didn't hang up new flyers this weekend. I'd say 50% on purpose. 1, I was lazy, but 2, I have like 80 conversations going right now. [laughs] Again, not like actively going, but I can't keep on doing this forever.

Jenny: There's no contract for these friendships. That's never what it was about for Niky. It was about mimicking those little things, the kind of play with strangers that can make your day, a flirtation at the coffee shop or a joke exchanged in an elevator. The problem right now is that we're living in a world where laughing out loud can actively spread the virus. Niky was able to find a way to do it safely.

Niky: I will say that, yes, there are people that I have felt the energy is really good. As the kids say, "We're vibing." I'm definitely vibing with certain people better than others, but what I think is appropriate to say is that, if you're listening and we talked, you were the person that I vibed the best with. It's you. I can't wait to continue talking to you.

Kai: That was Niky Crawford in Chicago brought to us by our reporter, Jenny Casas. Those are our two submissions for the 2020 time capsule that WNYC is making. Now, I really urge you to submit your reflections on 2020 as well. Here's how it works. Go to wnyc.org/timecapsule. You're going to find a couple of things there.

First, there's a link to where you can submit whatever you want to memorialize. The idea is that this is our first draft of the history of this remarkable year. What do you want included? Click the link and record. Second, you'll find some of the stuff that WNYC has already put into the time capsule, some of our own reporting and some of your phone calls. We'll take all of this and all of your submissions and put them on a hard drive and store them on top of the Empire State Building right next to our broadcast transmitter up there.

We'll open it again in 2030 to see what our 2020 selves had to say about this year. As we conclude 2020, I want to finish by thanking you, first off, all of you and all of the people who work on this show for helping me make it a meaningful space. Let me name some names here. Each week Kevin Bristow, Matthew Marando, and Jared Paul do all of the engineering magic to make both the show and the podcast possible, additional engineering help this week from Joe Plourde.

Our theme music is written by Hannis Brown and performed by the Outer Borough Brass Band. While it's my voice you hear each Sunday when you tune in, there are a bunch of producers and reporters and editors who each week are helping to figure out who I should interview and what I should ask them and who are also out reporting and making the stories that you hear.

Those people include Carolyn Adams, Emily Botein, Jenny Casas, Marianne McCune, Christopher Werth, and Veralyn Williams. They also include Karen Frillman, who is our executive producer and who has really been my personal mentor in making radio. A special thanks to her. A special thanks also to WNYC's program director Jacqueline Cincotta and the head of live radio, Megan Ryan, having faith in us to join all of you in this time slot each week.

Finally, of course, a special thanks to all of you for spending this time with us. The show is ultimately about community, the community of people who I said want to share joy and work of living in a plural society. Thank you for being part of it. I'm Kai Wright, and I'll talk with you in the new year.

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.