The Legacy of Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers

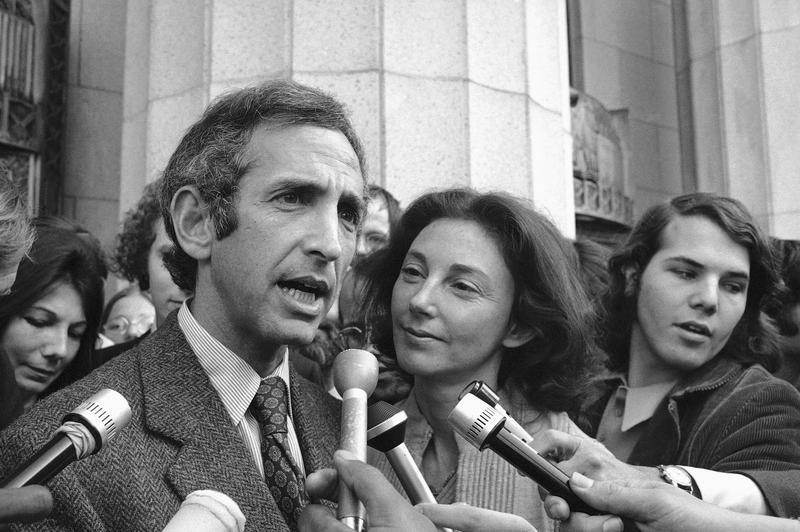

( File / AP Images )

[music]

Brooke Gladstone: On this week's On the Media, the legacy of Daniel Ellsberg and the other truth-tellers of the Vietnam War era.

Daniel Ellsberg: I've enjoyed reading the papers the last week. I've been reading the truth about the war in the public press, and it's like breathing clean air.

Matthew Reese: McNamara wanted academics to have the chance to examine what had happened. He would say to us, "Let the chips fall where they may." I think guilt was a bigger motive and encouraged--

Les Gelb: The notion that this was a definitive history, is just plain wrong, because we didn't have that kind of access, and we never were allowed to do any interviews.

Laura Palmer: It was 3:00 in the morning, the phone rang, I picked it up. He said, "I got a job offer. Vietnam, six months, do you want to go?" I said, "Sure." Haven't you ever done dumb things for love? Come on, Brooke, tell us.

Speaker: My father had a favorite line from the Bible, which I used to hear a big deal when I was a kid, the truth shall make you free.

Brooke Gladstone: What we learned, what we haven't. It's all coming up after this.

From WNYC in New York, this is On the Media. I'm Brooke Gladstone. Daniel Ellsberg died, as we posted last week show. Even though much has already been said, we need to say a little more because Dan has surely been vital to the On the Media project. Really any project charged with scrutinizing stories told about the world and distilling the truth from a churning around a burning funk, Dan Ellsberg knew when to lean in, and when to leave things behind. As a kid, he was gifted at the piano. That's him playing in this recent cell phone recording kindly sent to us by his son, Robert. Not bad, but some 75 years ago, he practiced many hours every day, until 1946, when he was 15. A car crash killed his sister and mother, and he left the piano, his mother's dream, behind.

A long time later, after years spent in Vietnam in the Defense Department and at the RAND Corporation, he left behind the career as a cold warrior he built at the seat of power and nearly gave up his freedom altogether because of the war. "No one is ever going to tell me again," he said, "that I have a duty to lie."

Daniel Ellsberg: I found myself handing out leaflets in this long vigil line. At first, I simply felt ridiculous. I knew that if any of my colleagues had ran to the Pentagon, or somehow to catch word of my doing this, they would think I had gotten mad.

Brooke Gladstone: If you'd ever met Dan, you were bound to like him very much, because he was zesty, contagiously curious, and so very gracious, even in disagreement, and he had a generous spirit. Once when he happened to be in our office, he performed some magic tricks for our avid star-struck staff, but to understand why all this matters, we need to offer a brief recap when he became America's Most Wanted as perpetrator of the greatest press leak in America ever.

The secret 7,000-page history of US involvement in Vietnam, going back decades, revealed Presidents of both parties and officials lying to the public and lying to each other. One of those officials was Daniel Ellsberg, and he wanted that history out.

Daniel Ellsberg: I'd been trying to get them out through congressional hearings, and was promised several times by various senators or congressmen that they would move it ahead, but each time they backed off for fear of the retaliation by the executive branch. Finally, I decided the only way to do it was to go directly to the newspapers.

Brooke Gladstone: TV followed in the pusillanimous footsteps of Congress.

Daniel Ellsberg: The TV stations, The NBC, ABC, CBS. CBS took the longest to decide no, the others were quite quick. They took a couple of days, actually, to decide that they didn't want to fight on this one. That's why I gave the interview to Cronkite, by the way, I felt that they'd behaved more respectively in that respect than the other networks.

Brooke Gladstone: Here's Dan in that 50-year-old interview.

Daniel Ellsberg: I've enjoyed reading the papers the last week. I've been reading the truth about the war in the public press, and it's like breathing clean air.

I remember very well the circumstances of that.

Brooke Gladstone: I spoke to Ellsberg on the 30th anniversary of all this in the summer of 2001.

Daniel Ellsberg: That was in a private home in Cambridge, Massachusetts. I can see that now. The FBI was searching all over the country, to some extent, the world, for me at that time. They said it was the biggest FBI manhunt since the Lindbergh kidnapping. When I made that interview with Walter Cronkite.

Brooke Gladstone: Then, Nixon's infamous Plumber Burglarize Ellsberg psychiatrist office, a caper that led in a straight line to Watergate, pursued as a spy he finally surrendered to the FBI, but then the Nixon White House went too far dangling the plum post of FBI chief before the presiding Judge.

Judge: Mistrial.

Daniel Ellsberg: The judge ruled that the government had so tainted its own case as to make a fair trial impossible.

Brooke Gladstone: Ellsberg and his co-defendant, Tony Russo, facing decades behind bars were freed. Meanwhile, the newspapers who published parts of the Pentagon Papers faced legal penalties too, but New York Times journalist, Niels Sheehan, who first took on the leak, set the standard for clarity and courage. "This was about history," he said, "not ongoing operations." The High Court agreed and lifted the injunctions against publication. Justice Hugo Black wrote that, "In revealing the workings of government that led to the Vietnam War, the newspapers did precisely that which the founders hoped and trusted they would do."

Richard Nixon: Son of a bitch thief is made a national hero and is gonna get off on a mistrial.

Brooke Gladstone: Richard Nixon.

Richard Nixon: The New York Times gets a Pulitzer prize for stealing documents. They’re trying to get at us with thieves! What in the name of God have we come to.

Brooke Gladstone: How would you gauge the courage of the press, pre-Pentagon Papers, and post-Pentagon Papers?

Daniel Ellsberg: Well, courage is contagious. 19 papers faced prosecution one after the other. As one injunction went out, another one took up that flag and carried it forward. That was courage. They were helped by the fact that The Times had, and the Post had unusual courage and being the first to do that. Having once had that experience, I think a generation of journalists grew up with a good deal of pride and saying, "We did our job. We have the guts to do this, and we can do it again." That was a very good precedent.

Brooke Gladstone: What about the impact of the papers on government officials?

Daniel Ellsberg: Well, I think nothing you can do can keep men in office from trying to hide their mistakes, their bad predictions, their crimes. When I say that, it's not from inside knowledge at currently, it's from my experience in the government when I was surrounded by intelligent, conscientious patriotic people who knew from month to month and year to year that their government, Republican or Democrat, was deceiving the public terribly about the information that had and the expert opinions he was getting. Those people, I among them, kept their mouth shut far too long.

Brooke Gladstone: In current whistleblower news, we just passed the 10th anniversary of Edward Snowden's leak about government surveillance. He says, from Moscow, that he has no regrets. This week, Democratic Senators Ron Wyden and Richard Durbin, together with Republican Senator Mike Lee, reintroduced the federal shield law that would, "Ensure reporters cannot be compelled by the government to disclose their confidential sources, and also protects their data held by third parties like phone and internet companies from being secretly seized." The idea is anathema to Arkansas Senator Tom Cotton, who has offered the Pentagon Papers as Exhibit A in his opposition. He says such laws grant journalists privileges to disclose sensitive information that no other citizen enjoys. That's not true. Not just professionals who get paid to report the news would be protected, but anyone who commits an act of journalism and every citizen benefits.

Ellsberg, a true patriot, devoted the rest of his life to encouraging and supporting whistleblowers, and wondering where they all are. Tom Devine is the head of the Government Accountability Project, and he knows where they are. He says that Dan made the lives of potential truth-tellers easier by catalyzing a kind of cultural revolution.

Tom Devine: When I first came to the Government Accountability Project, the US was the only country in the world with a whistleblower law. We passed it in 1978. The second one wasn't until 1998, in Great Britain. Now there's 64 nations globally that have whistleblower laws. The United Nations has whistleblower protection, the World Bank has whistleblower protection, but it wouldn't have happened if there weren't a cultural revolution first. That cultural revolution created the political base to have the legal revolution that allows people to be lawful whistleblowers because now they have some rights.

Brooke Gladstone: When journalists report information that the public doesn't want to hear, they're routinely called traitors, especially in this profoundly fractured cultural environment. Do you have any proof that whistleblowers have a better rep than they used to have?

Tom Devine: In 2006, there was a survey of swing voters after the voters switched Congress from being all Republican to all Democrat. The question was, what is your priorities for this new congress?

83%, number one, said, "Reduce illegal government spending," which was predictable. Number two, ahead of ending the Iraq War, National Health Insurance, lowering taxes, the stronger rights for government whistleblowers. For the recent congressional elections, Marist poll found that 86% of probable voters wanted to have stronger rights for whistleblowers. Freedom of speech to expose abusers of power has won the Cultural Revolution.

Brooke Gladstone: You said it wasn't surprising to you that Ellsberg turned on the institution he really believed in. You said it's not unusual.

Tom Devine: It's not unusual at all for people to become disillusioned. What made Mr. Ellsberg stand out is he didn't just become cynical, he acted on the truth. In that sense, he was a real pioneer. Most folks would just shake their heads and say, "What are you going to do? I'm not taking any risk." He was wanting to risk everything when he learned the truth. It took him years of agonizing. That's very common in my experience.

Brooke Gladstone: You say it creates a very intimate crisis?

Tom Devine: Most whistleblowers that I've worked with, they've been in an organization for 20 to 40 years. That organization is their personal identity. It's their mission and their calling in life, and they believed in it. Then they stumble onto something and it's absolutely a life's crossroads. When someone comes into Government Accountability Project, and they haven't blown the whistle yet, my first duty is to try and talk them out of it. First of all, they have a right to make a fully informed decision that they're going to be professionally destroyed. Friends are going to abandon them. They need to know what they're getting into. They need to discuss it with their families that's depending on them, and so I need to warn them.

The second reason is because they have to make a firm commitment to finish what they started, because if they quit in the middle, the abuse of power they were challenging will be stronger and the aftermath of defeating them, and they won't have accomplished anything.

Brooke Gladstone: Ellsberg was always surprised that there weren't more whistleblowers.

Tom Devine: It doesn't surprise me. Mr. Ellsberg had extraordinary courage, and it took him years. We nickname whistleblowing, the sounded professional suicide. It means that a professional life that might have been very comfortable and successful is going to be a nightmare that you can't wake up from.

Brooke Gladstone: He did something that maybe no one had ever done before, but it was declared a mistrial, and he was let off the hook. Not really on the substance, it was the newspapers' trials that were finally decided on substance.

Tom Devine: His fate was the exception, rather than the role. Numerous whistleblowers are criminally prosecuted. On the corporate side, they're prosecuted for stealing the company property, the evidence of fraud against their government. On the civil service level, they're prosecuted for disclosing confidential information that's not classified. They're prosecuted for not being loyal to the government. They're prosecuted for conflict of interest. When you blow the whistle, the first thing that'll happen is a retaliatory investigation to find any dirt possible on you. That means there's going to be a poison cloud hanging over your head. Your life will never be the same.

Brooke Gladstone: Yet whistleblowers, over the past few decades, have changed the course of history more than any other time, you say, and that Ellsberg was the catalyst. Can you give me a few examples of whistleblowers we likely wouldn't have had without him?

Tom Devine: In the Iraq war, the marine science advisor, Franz Gayl, he was requested, semi-ordered, by the Chief Field General in Iraq to free up vehicles that would actually protect the troops against landmines. They're called MRAPs. They were using Humvees that weren't even designed to protect them against landmines. 90% of our fatalities and 60% of our casualties in Iraq and Afghanistan were from landmines. Thanks to his whistleblowing, the MRAPs were delivered. The casualties went down to 5% from landmines.

Nuclear power plants, and there was a story on Netflix about three nuclear engineers who stopped the three-mile island clean up from turning into a complete knockdown that would have taken out Philadelphia, Boston, New York City, Baltimore and Washington DC. They exposed that instead of losing track of 10,000 gallons of radioactive waste, it was 4 billion gallons of radioactive waste at our nuclear waste stuck, which forced a big upgrade in the cleanup.

Human rights abusers. Until not that long ago, people were coming in from foreign countries. The US government would stop them, accuse them of drug smuggling, without any evidence. Usually it was attractive women, usually it was near the end of a shift so they could get overtime. If they didn't find any drugs on the travelers, they would do body cavity searches. If that didn't work, they would take them to a hospital and do up to four days of laboratory tests, during which time those people couldn't contact their lawyers, their family, and thanks to a courageous customs inspector, Cathy Harris, that blew the whistle on this, that was changed from four days to two hours.

I could keep going on and on, but these people make a difference. The truth matters. They've been changing the course of history ever since they got rights under the Whistleblower Protection Act that can be traced back to Dan Ellsberg.

Brooke Gladstone: Thank you so much, Tom.

Tom Devine: Thanks for having me.

Brooke Gladstone: Tom Devine leads the Government Accountability Project.

Coming up, a man in charge of compiling the Pentagon Papers would like to correct the record. This is On The Media.