The Last Abortion Clinic in Mississippi

David Remnick: I'm David Remnick and I'm here today with my colleague, Jia Tolentino.

Jia Tolentino: Hi, David. I recently talked to a young woman who I'm going to call Jane.

Jane: I guess you could say I was the golden child so she would always talk so bad about my sister saying, "Oh, she got pregnant so young. She doesn't know how to take care of it," this and that. Then she'll turn around and tell her friends, "Oh, my other daughter, she's so amazing. She has AP classes. She's a STAR student," so much and so on. I knew it would be so hard for me to come up to my mom and just drop that bombshell and tell her, "Hey, I'm pregnant."

[music]

Jia: Jane is from Texas which is where I grew up. In the 90s in Texas as with now, sex ed is not mandatory in school. When it is taught, state law requires that abstinence be stressed as the preferred method of birth control and we all know how well that works. I remember growing up, abortion was talked about unequivocably as murder.

Jane: We did want a kid but then again, we just couldn't afford it. I was still in school. I was barely about to end school. I was about to graduate so it was just so close. It was just that fear of we're not going to be able to give it the life that we would want to give it.

[music]

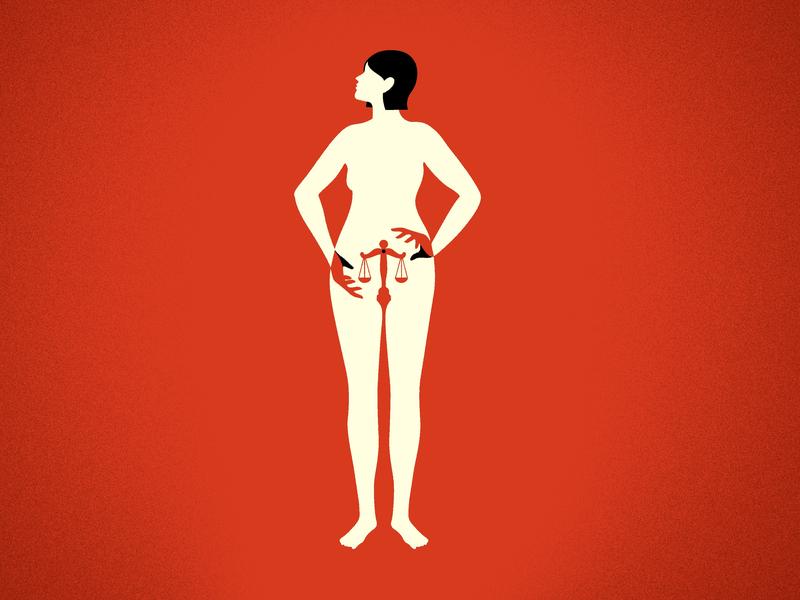

David: Hundreds of thousands of people seek abortions every year, each for their own reasons. At this moment, the Supreme Court is weighing cases that seek to end the constitutional right to abortion that was established almost a half-century ago. That is the subject of our entire program today.

Jia: Conservative states like Texas have been making it harder to get an abortion for years, decades really. They've taken measures to narrow a timeframe in which a woman can end a pregnancy, to complicate the process of getting an appointment, to restrict how and when clinics operate with the idea that many of those clinics will eventually shut down. Jane was 17 and in high school when she got pregnant. She had an after-school job at a fast-food restaurant. She told me that her morning-after pill, also known as Plan B, had failed.

Jane: We just drove around a bit, try to get our minds a little more calmer. Then that's when I started calling different clinics and trying to figure out how much money it was going to take because I was working at that time but since I was also underage, I just didn't know what to do.

Jia: You had never had the conversation with anyone in your life like, "What would I do if I get pregnant?"

Jane: Yes. The reasons why we kept it to ourselves, most of them or the main ones was because our families wouldn't accept us and we knew it wasn't going to go to a pretty path. It was going to be all messy.

Jia: Accept that you had gotten pregnant or accept that you needed an abortion or both?

Jane: Both. It was just really hard because it was just me and him dealing with it. We couldn't really tell anybody. Another reason why I didn't say anything personally is because how, I guess you could say, society portrays everything that, "Oh, if you get pregnant at 18, your whole life is going to fail you." I just didn't want to hear all that judgment from everybody at my school.

Jia: I'm sure you were also just so mad at your Plan B.

[laughter]

The number of times too, people are like, "Oh, why weren't you careful?" and you're like, "I took Plan B."

Jane: I tried.

Jia: Yes, I did my best here.

Jane: Luckily, I called a good clinic and she told me about Jane's Due Process and how to do everything, and what steps to take.

Jia: They told you, "Call this organization. They help minors in Texas get abortions." One of the centers of Jane's Due Process's work is that, in Texas, if you're a minor, you can't get an abortion without parental consent, without a judicial bypass. You have to make your case to the court. Tell me about, how does getting the judicial bypass work?

Jane: Well, as soon as you talk to your attorney, you start figuring out what you want to do and what clinics to go to. First, you have to confirm that you're pregnant because a pregnancy test can be false sometimes. We would have to do the ultrasound.

Jia: Oh, wow.

Jane: It was crazy because when I did it, I had to do it about three times because the first time I did it with one doctor but then apparently that doctor left and I couldn't do my abortion with a different doctor. That's one of the rules they had. If you're going to have an abortion, you're going to have to have it with the same doctor who took your ultrasound. I was so upset, so scared, so nervous because I remember when I was doing the Zoom meeting, it was before--

Jia: With the judge, you mean?

Jane: Yes, with the judge.

Jia: Were you ever afraid that the judge was not going to approve?

Jane: Oh, yes. A part of me said that I was going to fail and that it wasn't going to go my way. I was just so paranoid about what's going to happen. I was just so nervous because again, it's a judge. You don't really think you got to see a judge unless you got to do a crime. It feels like the abortion is a crime in one way.

[music]

David: Jia, the young woman you spoke to got an abortion in February, some months before Texas enacted the SB8 law, which is now being reviewed by the Supreme Court. That law is a near ban on abortions after six weeks. What would she have done under SB8?

Jia: SB8 prohibits abortions after six weeks and at that point, as we know, a lot of women don't even know they're pregnant. It's two weeks after a missed period if your periods are regular. As these clinics shut down under these regulations, it gets harder and harder to get an appointment at the ones that remain. Clinics in Texas are sending people out of state, which is enormously difficult if you are of a certain income level if you can't arrange your own child care.

I actually asked Jane this question, what would she have done if she had found herself pregnant right now. She told me, she put it this way, she said she would have just given up. She would have become a mother. She would have put her high school graduation on hold. She would have had a child at 18 that she wasn't ready for.

David: The other big case at the Supreme Court is from Mississippi, the case called Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization. Oral arguments are set for December 1st. The State of Mississippi has directly asked the court to overturn Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey which are, of course, the major precedents on abortion rights. The defendant there is Jackson Women's Health Organization which is now the only remaining abortion provider in the state of Mississippi.

Rachel Monroe: We are standing here on a beautiful October, Friday outside the Jackson Women's Health Organization. It's funny to think that all it's going to center on this one building which is a pretty unremarkable building except for the fact that it is quite pink. It is a beautiful pale pink. I believe they call it the Pink House. Let's go in.

David: New Yorker writer Rachel Monroe was there recently to meet with the clinic's director, Shannon Brewer.

[background conversation]

Rachel: Shannon Brewer, she's the clinic director.

Shannon Brewer: We've been seeing a lot of patients this week. The Louisiana clinics are full and then, of course, with Texas, you got the SB8 going on. Literally, the same week it came into effect, the very first day, our phones rang from eight o'clock until we left that day. It was Texas people and they were on panic mode. They were crying, they were upset, they were going through so much. Normally, we see patients three days a week. We're now seeing patients five and some weeks, six days a week.

Rachel: Oh, my gosh.

Shannon: Some weeks, yes. I have been here, it's going to be 21 years. I started out part-time as a sterilization technician. It was like, "It's just another job. I got me a job, I'm happy." Once I started learning the political aspects of it, it changed to, "I'm a part of something that's a little bit deeper than just clocking in every day." A lot of women really don't know what's going on out here. They don't know about the fight. They don't know that we're dealing with these new laws that they're trying to put in place and we're fighting all of these laws. They're amazed by it.

Rachel: Can you talk a little bit about who are the patients who come here?

Shannon: We serve all types of women. There is no one type of women. Of course, because we're here in Jackson and we're the only facility in Mississippi, we do serve predominantly a lot of African American women here. A lot of women who are already struggling as far as health care and stuff like that, they're already having issues with that, we serve a lot of those women, actually. We really do. Quick question, Rachel is this-

Rachel: The New Yorker writer.

Shannon: -The New Yorker. They want to know if you wanted to talk to them.

Doctor 1: Yes. I would prefer to remain anonymous.

Shannon: Most of our doctors do.

Rachel: That's totally fine.

Doctor 1: I've been coming here to Jackson Women's Health Organization for almost three years.

Rachel: Can you, I guess, maybe talk about some of the security staff that you have to do even just that you were trying to figure it out today?

Doctor 1: Yes. For safety purposes, we always use a rental car so that our personal car isn't able to be tracked or located. Just with the history of violence against abortion providers in this country, we try to take every precaution to be as safe as possible. Actually, back in March of this year, my identity was somehow made known to the protesters and then they ended up harassing the clinic where I work. That made me stop coming here for a little while, and then I ultimately found a new job. I'll be leaving Mississippi-

Rachel: Oh gosh.

Doctor 1: -but continuing to come here.

Rachel: What are you thinking about and watching with this Supreme Court case that centers on this clinic? A 15-week ban, what is that I guess, as a medical professional, is there any scientific basis to that?

Doctor 1: Absolutely not. It's basically just drawing a line in the sand. In general, first trimester abortions are a little bit safer than second-trimester abortions, but all abortions are much safer than carrying a pregnancy to term. Pretending like this is in a woman's best interest is just a farce.

Minister 1: Ma'am they just want to kill your baby. You got a little woman or a little man that deserves to live.

Rachel: There's the first patients of the day are starting to leave the clinic, a hectic vibe here at the Pink House.

Minister 1: Let's pray. For these innocent little children who are having to die at the murderous knife of this abortionist doctor and all of these evil, wicked supporters, Father, Lord Jesus, I pray that you would just open the flood gates of terror in such a way that it would help them see that they are going to die and go to hell if they do not trust you as your Lord and savior. Lord, that there would be a--

Rachel: I'm wondering if I could see the literature that you're handing out to folks or something.

Minister 2: I was just telling John about this campaign that Life Action lead. It's what is 2,3, 6, 3.

Rachel: What is 2, 3, 6, 3?

Minister 2: Is the average number of babies that are aborted in America every day. Our thing is scientifically, DNA says it's a human being from the very beginning of conception. Now, it might not look like you and me, but it is a human being. At what point is it okay to abort that? 20 weeks where they've got some hair and eyelashes and totally everything's working.

John: Everything's present.

Minister 2: Everything's present. It's just a matter of, do you believe that it's a human being from the beginning or not? We do.

Rachel: How long have you been coming out here? How long have you been up to this?

Minister 2: I think about 12 years.

Rachel: Oh, gosh. Wow. Are you paying attention to the Mississippi law that's now being heard by the Supreme Court case, is that-- Oh, you're smiling at that.

Minister 2: Well, can I say I don't have time to really-- my heart is here. My heart is trying to help women here. I do pray that Roe v. Wade gets overturned. I would love to see it go back to each individual state. I think that's where it belongs.

Rachel: If this clinic does get shut down because whatever happens in the courts, do you all get to retire or you move on to--? What happens next?

Minister 2: There's still going to be women to help and babies to help. I would love to see us have maternity centers ring up where we could minister to these women, mind, body, and soul.

Patient 1: I know everybody's outside picketing and wanting me to love your child. I do love the child that I have, but I just don't feel like that. I can't go on with the pregnancy. What brought me here are the severe laws in Texas. I had to drive here to be able to make my own decision as a woman. This clinic is a lifesaver. I am extremely sick. I am not able to function, I'm not able to drink any water, I'm not able to hold any food down, I'm not able to care for my other child. It's just not ideal for me to have another kid.

Rachel: Did you come here from Texas?

Patient 1: I did. I'm from here. I'm from Mississippi. I just live there, better opportunities, living a better life with my kids. I'm so glad to be able to come home and do this. That's it. I'm married. It's not like I'm having a kid and my husband doesn't know it's by somebody I'm just randomly having sex with. No, we're both business owners. We're married and we know the type of life we want to live. We don't want a bunch of kids. I can't handle it, my body can't handle it. It's a decision we made.

Rachel: What impact did the Texas law have on your life?

Patient 1: I couldn't make my own decision. I feel like that's taken away from me. I feel like somebody else is telling me what I should do with my body and it's not right. It's my body, it's my decision, it's my choice, it's my life. It's my soul if it's going to hell. I just feel like they don't have the right to do that, especially a man. You all have to do nothing. We have to do everything and you have a decision on what I'm going to do? I think not. I drove all night. I left at 2:30 in the morning with my six and three-quarter year old. We drove all night, dropped them off with grandma and I'm here and I don't feel bad one bit about it.

Rachel: Thank you so much for sharing that.

Patient 1: No problem.

Rachel: Have a good day, everybody. I appreciate you all letting me come in and bother you.

Group: Thank you and you too.

Rachel: Do you think there's a chance that you all will have to close?

Shannon: I don't see us closing, but we don't know. Like I said, this is probably the first time when people ask me about it that I don't have a definite answer because of the fact that it's the Supreme Court and they took it because I still can't believe it. I usually was like, "No, we're going to fight this to the end. We're going to do this. We're going to do this." This time it's you really don't know what's going to happen.

Rachel: Are you going to go for that argument? Are you going to go up there?

Shannon: Yes, we're going.

Rachel: If it goes not in your favor, then it's like the case has the name of this clinic. Does that bother you at all?

Shannon: No, that doesn't bother me, the fact that it has the name of the clinic because whichever direction it goes in, every pro-choice person in America, they'll know that we were here and we fought all the way to the end. They will know that we were here for them at all times. I don't have a problem with that at all.

Rachel: If they rule in a way that's not in your favor, then what happens next?

Shannon: The next thing is we figure out how to help women in whatever way we can. The next step is not to just, "We lost," the next step is always, how do we make this work? That's what women do. We figure out how to make something work.

[music]

David: That's Shannon Brewer at the Jackson Women's Health Organization with The New Yorker, Rachel Monroe. The Supreme Court is hearing arguments in their case in December. In a minute, constitutional scholar and New Yorker writer, Jeannie Suk Gersen takes a look at the Supreme Court and the legal road ahead if they end federally guaranteed abortion rights.

[music]

[00:19:16] [END OF AUDIO]

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.