The Kremlin's M.O.

( Dmitry Serebryakov / Associated Press )

[music]

Brooke Gladstone: On this week's On the Media midweek podcast, we're re-airing a piece we ran in September. It's reported by OTM producer Molly Schwartz, who until the war in Ukraine started, was a fellow on a journalism program in Moscow. The situation on the ground for independent journalism in Russia is dire and getting worse daily. Ekho Moskvy and TV Rain went dark last week. This week, some international news outlets announced that they're pulling their journalists out of the country in fear for their safety. The current crackdowns are severe but silencing dissenting voices isn't a new thing for the Kremlin. In the months leading up to the Duma elections, the Russian government came down hard on news outlets and other organizations.

In this story, Molly explains how death by bureaucracy is the Kremlin's MO.

Molly Schwartz: On July 15th, Sonya Groysman lost her job.

Sonya Groysman: It wasn't the best day of my life, I can tell you.

Molly: Groysman is a 27-year-old Russian journalist who used to work at an investigative news outlet called Proekt.

Sonya: I did a podcast which told the stories of Russian doctors who were on the front lines against coronavirus which was based on doctors' diaries. It was the only podcast that conveyed a realistic picture of what was happening in Russia's hospitals.

Molly: Back in July, the Russian government went after Proekt calling it, "Undesirable organization," and basically, banning it from the country.

Sonya: Undesirable organization means that all the projects, all the things we did became illegal.

Joshua Yaffa: Proekt was releasing one high-profile fascinating and impactful investigation after another.

Molly: This is Joshua Yaffa, Moscow Correspondent for The New Yorker.

Joshua: It specialized in the brave unflinching, hard-hitting investigations that were hard to find and weren't being done by outlets based in Russia.

Molly: In Russia, there are certain people, like Putin's allies, who you can't touch, but Proekt went there.

Joshua: Russia's Interior Minister, people from the so-called Siloviki, the very powerful top officials from the country's security services. They even wrote an investigation that appear to suggest Putin might have a 17-year-old daughter from an extramarital affair and both, this young woman and her mother seem to benefit financially from certain ties to Kremlin-linked institutions and banks.

Molly: This is the reporting that got the outlet shut down, putting Sonya Groysman out of a job. With her new free time, she took a trip to Sochi, a vacation town in the South of Russia.

Sonya: Just to think, "What's next, what should I do now?"

Molly: On July 23rd, she was sitting on the coast of the Black Sea, just watching the waves.

Sonya: This day was stormy, it was rainy. I just was looking at the waves and thought, "It's like my life."

Molly: Then her reverie was cut short when her phone started buzzing like crazy.

Sonya: 20 messages in a minute, I started getting.

Molly: She opened one and clicked the link.

Sonya: The link to this list where my surname was 31 on this list.

Molly: Sonya Groysman's name had been added to the Ministry of Justice's list of foreign agents.

Sonya: I realized that my life is going to change right now.

[music]

Molly: Since 2012, the Russian government has used this foreign agent label to shut down organizations it sees as antagonistic.

Speaker 1: The wave of police raids against non-governmental organizations, foreign cultural organizations, and human rights groups continues in Russia with the latest targets the Helsinki Group and Memorial, Russia's oldest human rights organization.

Speaker 2: We are seeing a downright hunt for human rights groups. They want to force us to declare that we are foreign agents. They're hunting us down.

Molly: They went after Transparency International, the MacArthur Foundation, the election monitoring group Golos.

Joshua: This foreign agent legislation was continually expanded by the Kremlin to cover more and more groups and more and more segments of society.

Molly: In 2017, the law was expanded to specifically target the media. In the last few months, they've been on a spree.

Joshua: This all began in April first with the targeting of Meduza, an online publication that had been founded by journalists who had found themselves homeless during previous waves of media crackdown.

Molly: A media startup called VTimes was named a foreign agent, then the trickle became a stream, and then a river.

Joshua: Then came Proekt, then came an outlet called The Insider which specializes in data-driven investigations and often cooperates with Bellingcat. After that, we saw a TV Rain television channel which was the largest media outlet name to the foreign agent registry.

Molly: One of the most surprising things that happened in this time, the authorities started adding the names of individual journalists to the list. That's what happened to Sonya Groysman.

Sonya: To become a foreign agent in Russia, you have to publish something on social media or in a media publications and receive a financial transfer from abroad, that's all. Even if your-- I don't know, American grandma will send you $20 and you post something on social media, yes, you're a potential for an agent.

Alexey: The Russian foreign agent law was specifically designed to destroy you, drive you out of business.

Molly: Alexey Kovalev is an investigations editor at the news outlet Meduza. Brooke spoke to him when Meduza was first targeted.

Alexey: Not in one fell swoop like the government raids your offices and confiscates your electronics and arrests the journalists, no, it's not like that.

Molly: "It's the bureaucratic hoops you're forced to jump through," says Kovalev, that can be fatal for a news outlet.

Alexey: We have to put a massive ugly legal disclaimer on top of everything we publish. That includes all ads and promotional materials.

Molly: The disclaimer reads like a big scarlet letter of legalese. It says, "This news media/material was created and/or disseminated by a foreign mass media performing the functions of a foreign agent and/or a Russian legal entity performing the function of a foreign agent." The same rules apply to Sonya Groysman.

Sonya: Even if I post-- I don't know, flowers or my cat, I have to put this disclaimer.

Molly: I checked out Groysman's social media and that block of text, all caps, is in every post, every Instagram story, every comment, every response to a friend's comment.

Sonya: Every time I post something, I feel that I'm taking a risk.

Molly: She'll be fined if she doesn't comply. First ₽10,000 which is around $140, then ₽50,000 which is around $685.

Sonya: On the third time, there is the prospect of a criminal case, up to two years of prison.

Molly: Just six months ago, Russian journalists would jump from news outlet to news outlet as some were shut down and others started up, but now, even that option is disappearing.

Joshua: They could become professional breakdance buskers who work in the Moscow metro or they could go gather mushrooms in the Siberian taiga forest and they'd still be foreign agents. They carry that designation with them.

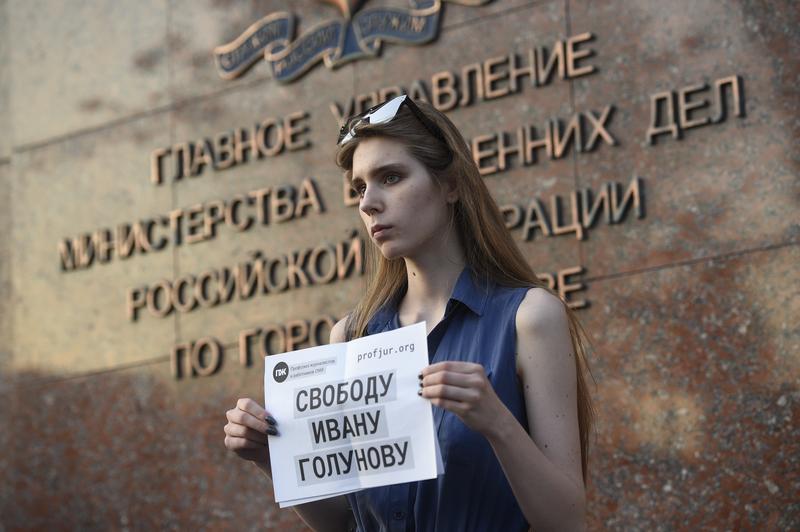

Molly: Last month, Sonya Groysman went to a protest with a small group of journalists outside the headquarters of the FSB, that's Russia's main security agency. They took turns holding signs, rotating one by one.

Sonya: It is prohibited to protest in front of FSB building, but one-person protests are not prohibited.

Molly: When it was Groysman's turn to pick it, she took the opportunity to perform some political theater.

Sonya: I just came there with a sign on which I had written nothing more than the full text of this 24-word disclaimer.

Molly: The disclaimer, the chunk of legalese I just read you a moment ago, and she was only there holding that sign for a few minutes before she was approached by men in uniform. What happens next is all captured on tape by Groysman. They grab her, take her to a police station and sit her down in a large assembly room. A portrait of Putin hangs on the wall. An officer starts to copy down the text on Groysman's sign to include in her arrest papers.

Male Speaker 1: [Russian language].

Molly: The police officer complains that the text on her poster is too long and the language is so burdensome. He asks Groysman if it would be okay if he just takes a picture of it with his phone instead of having to write it all out. Groysman tells him that she's required to put it in front of anything she publishes.

Sonya: I was like, "That's the law. You're a policeman, it would be great if you read it."

Molly: The entire exchange is documented in a podcast that Groysman started with her former colleague Olga Churakova whose name was also added to the foreign agent list in July.

Sonya: We started recording a podcast called Proekt [unintelligible 00:09:41] which means in English, "Hi, you're a foreign agent," about what life is like for us in this new reality.

Molly: In the second episode of the podcast, which like every episode, starts with the disclaimer. There's a scene in which Churakova tries to get a job at a fast-food chain that makes blini, the delicious Russian pancakes. Churakova calls and asks if they have any open positions.

Operator: [Russian language].

Olga: [Russian language].

Molly: The woman on the phone says, "Yes," they're looking for cooks and cashiers.

Operator: [Russian language].

Molly: Churakova asks if it's possible to get a job as a cook without any prior experience.

Olga: [Russian language].

Molly: Yes, it's possible.

Operator: [Russian language].

Molly: Churakova then explains that she's a journalist and she's been designated as a foreign agent.

Olga: [Russian language].

Molly: The woman on the phone says she's never heard of this before.

Operator: [Russian language].

Molly: But asked Churakova to write to her supervisors and explain the situation.

Operator: [Russian language].

Molly: Churakova does not get the job.

Tikhon Dzyadko: It is like the side that you were holding on which there is a text, "Don't work with him and don't talk to him."

Molly: Tikhon Dzyadko is the editor-in-chief of TV Rain or Dozhd in Russian. He told me about how it's the stigma of this foreign agent label that's been so painful for him.

Tikhon: For example, when you're designated as foreign agent, almost 100% that people from the government would deny talking to you. These 24 words, it's not the worst part but it's the stupidest part.

Molly: The worst part, he says is the idea that they're traitors to their country.

Tikhon: We think of ourselves as patriots and everything what we're doing here, [unintelligible 00:11:36] to the station over 11 years of its existence, we are doing for the best of our country. We just want our country to be better. I want my kids to live in a better place than the place where I grew up.

Molly: For Dzyadko, because he's Russian and he works for a Russian organization, and above all, he does this journalism because he really cares about Russia. That's what's made this foreign agent label so weird and confusing. They'd been anticipating some kind of pressure from the government because of what they were broadcasting last winter.

Joshua: If we want to isolate the most recent catalysts in this long story of increasing pressure and repression.

Molly: Joshua Yaffa.

Joshua: It would be fair to talk about the poisoning and then return of Alexei Navalny.

Molly: Alexei Navalny, the leader of the opposition and official thorn in Putin's side. He was poisoned in August 2020, taken to Germany for medical treatment. Then he returned to Russia and was immediately arrested, which led to protests.

Joshua: Not just in Moscow, but in dozens, if not 100 cities around Russia, I think, the Kremlin was certainly spooked.

Molly: Tikhon Dzyadko said 10 million people watched their coverage on YouTube. This is, I think, one of the most important parts of this whole story, who in claims that Russia's foreign agent law was actually inspired by a lot in the US, the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, which put a label on outlets like Russia Today. Media that are a Department of Justice consider as foreign propaganda. Joshua Yaffa of The New Yorker isn't buying it.

Joshua: I think it's a ridiculous and absurd comparison. As far as I understand, the far registration essentially ends there. In other words, you're added to the registry, you're not required to add some cumbersome disclaimer to everything you publish.

Molly: Being a journalist in Russia is like a dance, perhaps the tropak: the classic Slavic folk jig that you might know from The Nutcracker.

[music]

Molly: The dancers do these complicated whirls and squats and kicks, as the music speeds up to a frenetic pace, leaving all parties panting for breath, as the curtain falls. Russian journalists too, are jumping and twirling quick on their feet, just trying to stay a few steps ahead of the Kremlin, and still perform the essential parts of their job. Despite what you might think, they are doing their jobs.

Joshua: Independent journalism in Russia is perpetually under threat and under pressure, but it's not completely gone. I think that, oftentimes, in the American conversation, we don't acknowledge the fact that there are these journalists who are still managing, despite all the difficulties thrown at them, do work that is extraordinary and worthy of our admiration.

Sonya: We can still report things and we can earn money. We can be in the profession.

Molly: For Groysman's relatives who grew up in the Soviet Union, however, the fear is a little more ingrained.

Sonya: My grandparents think that I have to stop it, just to be silent. Someone on the top will forgive you, and then exclude you from this list. We have YouTube, we have Instagram, we have Telegram, we can distribute the information all the ways. Yes, it will be harder and harder to work as a journalist, but all the people cannot be silent.

Molly: The tempo is gradually increasing, but for now, the dance goes on. For On the Media, I'm Molly Schwartz.

[music]

Brooke Gladstone: Six months later, it seems as if the dance has, for now, at least, been halted. Join us later this week one we'll be taking a closer look at what's happening to the Russian media. Till then, I'm Brooke Gladstone.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.