Keeping Score: Part 3

( Alana Casanova-Burgess )

Kali: Yeah, I'm trying to get recruited for volleyball so, yeah I'm trying to go to college for volleyball. Girls also might be walking in by the way.

ALANA: I’m standing with Kali Moore on the side of the gym, near the doors.

Kali: Yeah so this is my fourth, kind of third year, just because of COVID, um, I started as a freshman…

ALANA: Kali is a senior from Park Slope Collegiate, co-Captain of the Jaguars, the new merged team. She's an outside hitter, and does this move where she jumps up, her arm raised – and for a moment it looks like she’s suspended in air, her long braid floating behind her. Then in a flash, she spikes the ball down hard over the net.

[SOUND: Kali’s spike!]

ALANA: It’s very easy to see she’s one of the star players.

Two years ago, before Covid, and before the sports merger at John Jay, Kali played for the Jayhawks, the three-school team.

Kali: Like we were very successful and we were known for being one of the only predominantly Black and Latin teams in the final four. There's Susan, the red head over there, she was the only white girl on our team.

ALANA: By the way, Kali’s mom is white and her dad is Black. She says race was part of the team’s identity.

Kali: …just by, like, being predominantly Black and doing so well in like a pool of, like, predominantly white volleyball girls, we felt like we were fighting back against racism just by winning and presenting ourselves and just doing well.

ALANA: In other words, it was anti-racist just to exist as a mostly Black team in a sport dominated by white players, and to kick butt.

The team has these mediated discussions about difficult subjects – they’re called circles. The players have shared what that old team, the Jayhawks were like.

Kali:. We talked about, um, this one time where we were discriminated against at Brooklyn Tech and…

ALANA: This happened a few years ago, Kali wasn’t on the team yet. But Kali’s uncle was the coach – still is – and he says he remembers it very well. Here’s Coach Mike Salak.

Coach Salak: One of my girls on my team was involved in a theft at one of our games at Brooklyn Tech. And then the next time we showed up was for a playoff game against Millennium.

ALANA: If the John Jay Jayhawks won the game, they would go on to the playoffs. If they lost, the season would be over.

Salak: And the Brooklyn tech security guards act completely different, they line the team up. Yelling at us: ‘you’re not on the roster and you’re not coming in!’ They never used to check our roster. One of the security guards says, ‘you know, if y'all didn't have sticky fingers… right?’ This one incident happens. And all of a sudden, all my girls on my team are thieves.

ALANA: Salak remembers that the captain of his team was particularly upset.

Salak: She was vexed. She was like, ‘what is this prison? Like, what are you guys doing?’ She was so upset. Um, and before the game I asked her, ‘you know, how are you doing? You ready?’ She's like ‘Salak. I can't believe what happened.’ She’s in tears!

ALANA: Being profiled like this… it rattled them. They lost the game, and were eliminated.

But it didn’t end there. The players actually pushed for a restorative justice approach: to have a circle with the security guards from Tech.

Salak: They came to our school, sat in a circle with us. And every one of my kids said like how it made them feel.

ALANA: The guards apologized. Salak says it was heartfelt, and it felt productive.

Salak: But like, I imagine what that struggle would be like, if it was not just Black and Latin girls. You know, if it was like a multiracial group of people standing up for each other.

ALANA: This happened years ago, but it’s something the girls still talk about.

And it’s the backdrop to this season: what happens off the court shapes what happens on it.

[UNITED STATES OF ANXIETY THEME: VOLLEYBALL EDITION]

From WNYC Studios and The Bell, this is “Keeping Score” – a year inside a divided Brooklyn high school building that’s trying to unite through sports. I’m Alana Casanova-Burgess.

[MUSIC SWELL]

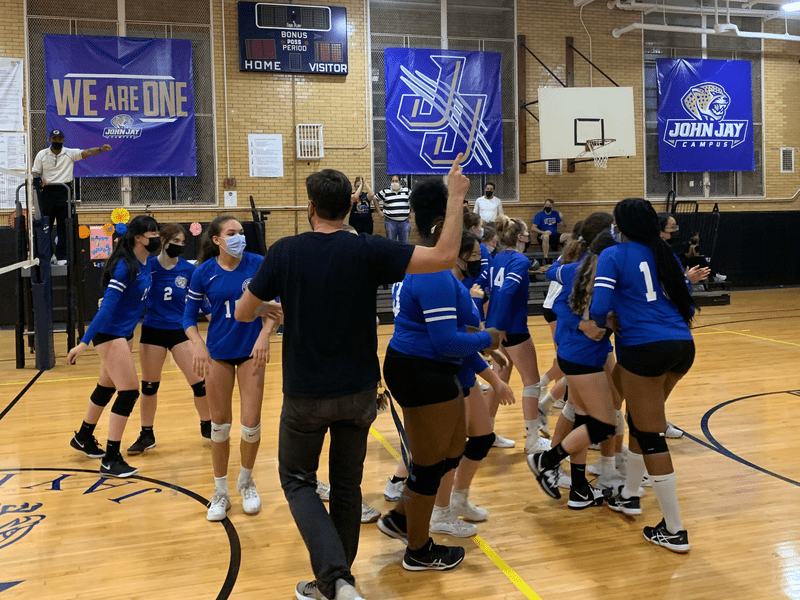

ALANA: It’s September. The girls varsity volleyball team, the newly formed Jaguars, practice in the second floor gym. It has big gated windows on two sides, and some bleachers where the players leave their backpacks and regular clothes during practice. The court still has the old Jayhawks mascot painted in the middle, it hasn’t been updated yet.

They start with stretches, then sprint back and forth across the gym, then practice skills – like blocking, setting, digging, hitting. Coach Salak starts counting down, and all the players run to form a huddle by the time he stops.

[Coach counts down]

And the whole time, on the court, they look like a team. All 23 girls text every morning to decide what color t-shirts to wear to practice, so they’re coordinated. If someone doesn’t have – for example, an orange one – someone else brings an extra. That doesn’t sound like much, but the four schools in this building are so separated that it’s already more interaction than many of the students have ever had.

And, then, there’s something about volleyball.

Angela: Just the sisterhood that it brings. Being on the court and working together to accomplish something.

ALANA: Angelina Sharifi, the co-captain from Millennium Manhattan – which is also part of the Jaguars. She describes herself as ethnically Italian-Iranian.

Angela: And like meshing is like the best feeling ever, like having a pass, set, swing, that's just like, you know, fits perfectly with one another. It's like that kind of unspoken connection that comes with volleyball is super satisfying for me.

ALANA: I’ve heard this from a lot of players, that there’s something special about this game.

In soccer or basketball, say, you’re spending a lot of time engaging with players from another team. Everyone is running around, you can literally touch your opponents. But in volleyball, you’re spending all your time on one side of the net – meshing, as Angie said, and becoming a unit. The six players on the court have to work together seamlessly, as one organism, to get that ball over to the other side of the court.

Salak: Truly, no, Michael Jordans can get you there. Like you truly are as strong as your weakest link.

ALANA: Coach Salak looks like a taller Coach Taylor from the TV show Friday Night Lights, but with a Brooklyn accent that gets a little muffled by his mask. He grew up in the New York City public school system playing volleyball, then went on to compete professionally in Europe. There aren’t a lot of public high school coaches with his level of experience.

Salak: In the public school athletic league? I can safely say, there's none. [laughs]

ALANA: He teaches at Park Slope Collegiate: economics, and a class called Participation in Government.

And his coaching goes beyond drills. This is a team with a particular set of challenges.

Salak: Yesterday I put a picture on the wall of them in our first, during our first scrimmage. And, you know, like it was all of them sitting on the bleachers and it was like, you know, the Black students right next to each other. It was all the John Jay girls next to each other. Then it was all the Millennium girls. So it was like, this is not, we're not mixed yet. Right. This is kind of a symbol of where we need to go, you know. I mean, the integration is the part, it's not that another school has been added in. That's not a big difference. Uh, but, the fact that most of the students we get from that school are white and Asian. That's a big difference.

ALANA: Some of the inequities showed up even before tryouts. There was a vaccine mandate for playing on team sports. That meant that some potential players weren’t eligible, and those students tended to be kids of color. In the end, of the 23 students who ended up joining the team, 22 were from either Park Slope Collegiate, Millennium Brooklyn, or Millennium Manhattan.

And by the way, a team of 23 is roughly TWICE the size of a regular roster. Which presented another challenge: making sure all girls get significant court time, despite vast differences in experience.

Salak: And so right away, girls who are new to the sport, And haven't had that exposure and that experience, they're at a huge disadvantage. So how do we make it equitable? When people are coming with, to you with stark differences in level of play, um, very different socioeconomic backgrounds.

ALANA: The "socio economic” aspect he's talking about is the influence of club volleyball. That’s the private league that some students compete in between seasons. It’s expensive.

Here’s Assistant Coach Veronica Vega:

Veronica: You know, it's club is, it's a cost, it's thousands of dollars to play,

Salak: Some clubs cost, you know, 10,000 dollars to play a year.

ALANA: Just to tryout is 100 dollars. And it’s a real boost for the players who can participate. This year, the new team, the Jaguars, have a lot of students with club experience.

Salak: We have an embarrassment of riches right now. We have, like, must be 10 girls, maybe more who are playing club, you know?

ALANA: And these girls with club volleyball experience – the ones getting the most playing time – tend to be white or Asian.

Salak: You know, like I came into this thinking, I'm going to coach this team like I coach my Black and Latin teams that I've had in the past. And, you know, beginning of the season, you focus on the first team to get them ready for the games. And at the end of the season, you switch it and you try and work on the second team because the next year, they're going to be your first team.

ALANA: A “first team,” with most of the starters. It’s not unusual for coaches of any sport to organize practice like this. The thought is that iron sharpens iron, you want your most skilled players to be playing with each other, making each other stronger.

At first, they called them the A and B teams – but that felt elitist, so they switched it to Blue and Gold. But – same difference.

And what was really stark was this: the high-skilled group barely had any dark-skinned girls. In other words, the split ended up having this racial dimension. And it hurt.

Lauren: So it’s the morning after the tournament, it’s 7:44.

ALANA: Lauren Valme is a junior at PSC, she plays middle, and she’s in the group of students helping us report this story.

Lauren: Yesterday we spent 10 hours at Cardozo High School and I have to say for most of the Black players, we did nothing yesterday. We kind of just all turned into cheerleaders, which is very much sad.

ALANA: Lauren was on the Jayhawks two years ago, as a freshman. She figured that as a junior, she’d get more playing time.

Lauren: But what we realized is that everybody who has played in the club, who has played outside of school is getting more chances. Why can't you let somebody else with a different skill set come and try? But all yesterday felt like was: win win win win win.

ALANA: Mariah Morgan, a setter from PSC, also Black – we heard her in the first episode trying out for the team – she was noticing this too. Although many of the people on the team are multiracial, including some of the starters, what she and Lauren saw were six players on the court who – for the most part – had lighter skin tones. And to them, that was a reflection of privilege.

Mariah: It was like, my stomach started to hurt. That's when I knew, like, I probably have to say something because this does not feel right, this does not look right.

ALANA: And even the players who were starters could feel something was off.

Elaine: It was when Mariah mentioned that, like she felt it was kind of unfair where we had like A and B team.

ALANA: Elaine Li is a very tall sophomore from Millennium Manhattan. She’s Chinese-American.

Elaine: …but like, I felt for her so much because like the coaches named that like Golden and Blue team, but we all, obviously, all knew it was just an A and B team.

Alana: So, had you noticed that before Mariah called it out?

Elaine: Oh yeah. All the girls knew it. It’s just Mariah, she was the brave one to like, speak up about it. It was pretty obvious.

ALANA: It was all feeling really heavy. Lauren and Mariah were thinking about handing in their jerseys in protest.

Lauren: I talked to my mom.

ALANA: Lauren again.

Lauren: She's like, ‘you don't need as much stress as you're putting yourself through right now. So if he's not like willing to make the change, then I think that you guys should leave.’

ALANA: So, she and Mariah went to Coach Salak and had a circle, along with an assistant principal.

Lauren: And I get, like, shaky when I'm nervous. And so I was just nervous just talking, you know, like he's right there, like in front of you

ALANA: They told him – how practice felt terrible and how they thought it needed to change, by being more truly racially integrated. They suggested mixing up the more experienced and less experienced players, breaking up the hierarchy.

Mariah: Basically I told him that to have the best skilled players only play with each other for most of the practice, those girls who were good are only just getting better. Like it's not changing anything. And it's especially just discouraging, at least for me. We have already lost a lot of Black and brown players because of the vaccination mandate. So I told him, ‘This is not the message you want to send. Like, how does that look?’

ALANA: Then, the two of them took a couple of days off from practice, to think.

Meanwhile, Coach Salak did some thinking too.

Salak: I feel like they've sharpened the struggle, right? And even for me, like, you know, I'm an old dog, sometimes hard to learn new tricks.

ALANA: Salak says he took their suggestions to heart, he started implementing them. And, it even made him reconsider how he’s been coaching all these years – dividing the players by skill, instead of mixing them up.

Salak: They saw a need for it. It was hard for me to feel what they were feeling, you know? Maybe for a long time as a coach, like the girls who were on the second team, maybe, maybe I made them feel a certain type of way too? You know what I mean?

ALANA: And, actually the other players liked the new strategy, too. Take peppering for example – it’s a warm-up drill where players go through all the volleyball skills, like bumping, setting, and spiking.

Elaine: The ball goes back and forth without stopping. And like, when we do like warmups, we have pepper partners. which our coach assigned to us, which I really like.

ALANA: And Coach would match people up with different skill levels. Sometimes, Elaine (Blue team) was paired up with Lauren (Gold team).

They both play middle, so in a way, they’re competing over who gets court time. But mixing up practice like this made them really close. The mixed practices were improving the team dynamic. And Lauren was feeling better enough to stay.

Mariah was pleased to see some changes too.

But that push for those changes -- the meetings, the circles, all of it -- had really taken something out of her.

Mariah: I don't want, I don't want to say that I don't enjoy it anymore, but I really liked to play and I like to play with my friends, it's taken a different form and it's, it looks different to me now, the sport as a whole. It looks more to me like the world than it does as a sport. Like, I can see how volleyball is, uh, is one of those sports where it's like an immediate reflection of like how the world works. I don't know. It sounds sad. Sorry.

Alana: Do you think it sounds sad? If you guys can figure out how to make this work, in the future, maybe there's something hopeful in that?

Mariah: Um-hmm. I think it's sad for me because it's a different job. Like it's changed from like, to play volleyball and to have fun, to like now to play volleyball, to do the podcast, to fight racism, to make sure everyone feels okay with the team, to talk to my friends about like what's going on, to having to digest certain things and figuring out my response to certain things… And I know, you have to try to turn that sadness into anger, because anger is like how it's gonna really, that's what this is going to drive you because you want to change it so bad. And you're mad at like the people who invented, like who invented and still maintain the system today. And so that's what it's like [sigh]

Alana: Yeah, Are you angry?

Yes. I'm angry. I'm angry at the DOE. I'm angry at PSAL. I’m angry at, I'm angry at the other coaches for not doing enough. And yeah, it just all makes me angry.

Steffen: You have navigated a very difficult situation, extremely well.

ALANA: Mariah’s dad, Steffen Nelson, who works at her school, Park Slope Collegiate.

Steffen: And I don't think that you really do have to carry all of this by yourself either. I think you have noticed something before other people have noticed. Um, I think our coaches do a lot of this anti-racist work with us and we dropped them in the deep end on this, right? We changed the world around them very quickly. They didn't have a season of transition. Volleyball started in August before school started and we had very little preparation for a merger that we fought a long time to get. Um, and then had very little time to prepare for.

ALANA: And even for Coaches like Salak and Vega, who listen to their players, who make adjustments…I can hear them weighing all these considerations as they think about strategy.

Vega: During our league play, we're going to have a lot of different opportunities where, we can put the mixed team and against certain teams. Right. But there are going to be certain days or certain tournaments or certain games where it's high stakes. And we talked about this in the circle where there, you know, if we lose, it might jeopardize us winning a championship.

Salak: You know, the other part of it is do you put a girl in and then to fight racism and to be equitable. And then, you know, what if she makes mistakes and then she feels like she's the reason we're losing and she feels bad, you know, it's like, is that something we want to put on a young person like that? You know, they have to be willing to do that, right? So, you know, it's challenging, right, because like you're used to being part of a competitive sport and now, you know, being less competitive feels like you're fighting racism more, it feels more equitable, right? It doesn't take away that desire to win a championship, though.

ALANA: If we could strip away all the external factors – the access to club volleyball, the treatment by security guards, even the different commute times – then equity would be a lot easier to achieve.

Salak: That's kind of where we want, right, we want to try it. We want to show that maybe that's possible, right?

Vega. We have to think as a team, you know, what is it that we want to do as a team? So.

Salak: yeah, what does winning mean to us? What is winning for us?

Coming up after the break… the volleyball team tries to figure it out. This is “Keeping Score.”

MIDROLL BREAK

MIDROLL MESSAGE:

Hi there, this is Jessica Gould, I’m a reporter in the WNYC Newsroom and I helped report this series. We’re really interested to hear how it’s resonating with you.

So before we go back to the story, I wanted to take a moment to ask you about your experience in high school.

Do you play high school sports? Or did you, back in the day? Were there ways that racial disparities showed up in your experience? Did you talk about it openly, and how was that? Did you try to do something about those disparities?

Tell us about it. You can record yourself on your phone or just write a message and email it to keepingscore@wnyc.org.

And if you didn’t play sports, we want to hear from you too. We know that racial disparities appear in different ways in different communities. How did you experience it in high school? And what did you do about it?

You can send us your emails and voice memos to keepingscore@wnyc.org.

Again, that's keepingscore@wnyc.org.

Thanks and now, back to the story.

[PAUSE]

ALANA: I’m Alana Casanova-Burgess. This is “Keeping Score.” And there’s gonna be pizza.

[gym sounds]

There are two birthdays to celebrate on the Jaguars: Kali’s and Angie’s.

Tina Moore: Please don’t destroy my house.

ALANA: Everyone is invited to celebrate at Kali’s house on a Friday after school. A priority for the coaches is to get everyone hanging out more outside this gym.

Lauren: There was, like, cupcakes and brownies and somebody brought cookies.

ALANA: Lauren was there.

Lauren: And then we ordered pizza later. And so when that pizza came, everybody was hungry, cause everybody was messing around playing games. I think they had darts though, they were playing that. And it was just fun.

Alana: Yeah. And lots of girls from Millenium?

Lauren: Yeah, I think all of them were able to come up, show up. Yeah. I think it was a big part of like seeing everybody as like a person and not as completely as somebody you're just there to like, compete with. It’s like, this person can actually be my friend. They're not like just my team member. They're my friend.

ALANA: And you can see it’s changed the way they play together.

Alana: What does it feel like when you're on the court?

Lauren: I don't know. It feels like a rush of energy now, more. Before it was kind of like down, like slow. Now it was kinda like I'm going for it.

ALANA: It’s mid-October and I catch up with Lauren after drills.

Alana: People seem to be, I don't know, coordinated and y'all are keeping the ball up in the air forever. [laughs]

Lauren: Yeah. We're definitely building more trust with each other. And I think everybody is working as a team, like a well-oiled machine. I mean, everybody's going to have a weakness. Like I might not be great at passing, but I'm a great hitter or blocker. You just need put them in. You need to give them a chance.

ALANA: After every point – whether they’ve scored one or given one up – the players come together for a second to pat each other on the back. Since they’re all wearing masks, they look like mimes who are celebrating or consoling each other, using these exaggerated gestures. Their body language is encouraging, even when someone makes a mistake. Which is part of the purpose of afterschool sports: to be encouraged, no matter what.

[Coaches: Brooklyn Tech is Friday, and it’s a home game!]

[MUSIC]

ALANA: The Jaguars are undefeated. 3 and 0 … gearing up for their first real test, a home game against one of their biggest rivals: the Brooklyn Tech Engineers.

The first team to get 25 points and outscore the other team by two… wins the set. It’s best two out of three. Set one:

[whistle!]

Tech started picking up points right away -- they were up ten nothing, and the gym felt tense.

But suddenly, the Jaguars shook off their nerves and found their groove, scoring point after point after point. They get to 25, and win the first match.

[cheering!]

And before the second one started, I asked Mariah and some of the other players… are you gonna get to play?

Alana: You guys gonna get to play?

Mariah and others: Nooooo.

Mariah: That’s not how it works.

Alana: Why do you say that?

Mariah: Um when it comes to like, certain teams – Malika, how would you describe it?

ALANA: Malika Rice is a junior from Millennium Brooklyn.

Malika: I mean when we play teams that we get a big lead on, usually, since our team is so big, we try to get other players in. But when we’re playing against teams like Tech or Bronx Science, which are really competitive and really good, we usually try to put our quote unquote ‘best players’ in. Which is understandable because it is a competitive league. But we get playing time in some games and we get playing times in scrimmages and stuff like that.

Mariah: Yeah, it’s a lot better than it was before when we first started.

Malika: But it’s a big team so it’s hard.

ALANA: I asked, do you want to be playing?

Malika: I mean, I do, but I’m also scared of messing up and making it worse for the team. But I do wanna play, because I think that’s the best way to learn is actually being on the court and learning how to deal with the nervousness that comes with playing. Like you can scrimmage all you want, but it’s not the same as playing an actual game.

Mariah: Exactly, especially with a team that plays at such a high level, I feel like it would be nice, but… you know…

ALANA: The second set flies by, and the Jaguars beat Tech!

[cheering!]

As it happens, two players without club experience, who are Black, got some court time too.

Salak: The untrained eye didn’t maybe see what they did but they had a few blocks where they touch it softly, slow it down for the defender, and then the defender had an easier job. So I was happy with what they did out there. I think getting them in in those moments is also really important -- where it’s like, it’s a big moment, you know? You could see, they were trustworthy, they didn’t make any mistakes, really. And that was it.

Alana: If the girls say to you on Monday [fade down]

ALANA: But I asked him, if the girls said to him on Monday, hey it’s actually more important to us that everyone gets to play, would he make that the strategy?

Salak: I don’t know. I’m going to have to go ‘no comment’ on that one. [laughs]

ALANA: A couple of weeks later, I caught up with Mariah to see how the season was going, how she was feeling about all of it.

Mariah: So now I'm kind of just like, especially with what happened yesterday, I'm kind of just, like, super disconnected from it right now. Like I really don't want to play.

Alana: What happened yesterday?

Mariah: Um… Me and my friends, uh, no, me and my volleyball team. I guess we're friends, too. Me and like half the girls… [fade down]

ALANA: They were at an away game, this was at the end of October, and a group of the girls asked a security guard if they could use a bathroom.

Mariah: And then she just looks at me, she gets this, an attitude. And then she's like, ‘ you're not allowed to be in here unless you're kicking a ball, setting a ball, touching a ball or spiking a ball.’ And then she looks to my other friends and then, like, in a completely different tone, the other girls she's like, ‘what do you guys want?’ And then they're like, ‘she's with us. Like, we're on the same team.’ I'm like, ‘miss, like we're literally on the same team. Like, can we please go to the bathroom?’

ALANA: The security guard keeps giving them a hard time, specifically asking Mariah – the only dark-skinned Black girl in the group – for her name. The other girls tried to have her back.

Mariah: Cause they were like interjecting themselves in between and they were like, ‘well, like why does she need to show ID? Like, no, we're not, she's not going to do that. We're not going to do that.’

ALANA: A multiracial group of people standing up for each other – like what Coach Salak wished could have happened at Brooklyn Tech a few years ago.

Mariah: But at the same time, like, it also felt like I was by myself too, because like she was specifically singling me out. All her attitude was towards me and they were even like, ‘what does she have against you? She doesn't, like…’ Obviously it's because I'm Black.

ALANA: Coach Salak wanted to bring it to administrators. But Mariah wanted to drop it.

Mariah: I mean, I’m telling you, because I know it’s important to do. But like I don't know. I just feel like if I do, it's just going to turn to this thing and I already do a lot concerning like my race and like how it, how it affects how I move, specifically in volleyball. So I cannot escape it. And I, I do have a lot of hope and like that this like next year it will be significantly better. And I know it will, it will. But there's also a lot just anxiety there too, because I'm just like, I don't want to have to do it again!

[MUSIC]

ALANA: It’s November. The Jaguars have finished the regular season with 8 wins, no losses, and they’re ranked first in the whole city-wide division going into the playoffs.

Alana: Alright I’ll take a medium in the pink then.

ALANA: There’s merch.

Alana: Thank you

ALANA: And, full disclosure, I’m a fan by now. And so is everyone else. News of their wins has spread, and the bleachers are packed with fans from all four floors. All this unbridled enthusiasm from outside the team casts the importance of winning in a new light. Winning is encouraging a kind of unity that goes beyond the court, even if it’s for just a couple of hours.

Students: Watching varsity, this is our second time watching them.

Alana: What do you think?

Students: They’re good, very good!

ALANA: I form a little focus group, from PSC, Millennium Brooklyn, and Law – all students of color, all from the JV volleyball team.

Student: There’s one girl on the team, her name is Ella. I wanna be like Ella, shoutout to Ella!

Student: Shout-out to Kali!

Alana: You all probably might be on the varsity team in a few years?

Students: That’s the goal! That’s the goal!

Student: I like to see the varsity girls being number one in the city! Like ahhh! They do really well and we do really well and we’re proud of them.

Student: Maybe if it was just Millennium by itself, or John Jay, or PSC, or Cyberarts downstairs by itself, we couldn’t have had that push that Vega and all the other coaches are giving us. And now we have something to look forward to, like, that’s gonna be us one day. So yeah, the merger is, like, good. Like definitely, it’s there.

Alana: How much of the merger is for you guys a story about race?

Student: Honestly… We really don’t look at color like that, it’s just one big family. And once we get together, it’s not really about our race demographic. We don’t really care about that. We just wanna play and have fun.

Student: Do the thing that we love.

ALANA: These students have never been on the Jayhawks or the Phoenixes. They've only ever known the Jaguars -- and it shows. They're being trained up in JV, and they're so enthusiastic to stick it through and be on the varsity team... they're what the future could look like.

But first things first… the Jaguars are headed to the city championship.

That’s next time on “Keeping Score.”

[MUSIC]

NOOR: “Keeping Score” is a co-production of WNYC Studios and The Bell.

The WNYC team includes: Alana Casanova-Burgess, Jessica Gould, Joe Plourde, Jenny Lawton, Karen Frillmann, Emily Botein, Wayne Schulmeister, and Andrew Dunn.

For The Bell: Mariah Morgan, Lauren Valme, Renika Jack, Thyan Nelson, Jacob Mestizo, Taylor McGraw, Mira Gordon… and me, Noor Muhsin.

Fact-check by Natalie Meade.

Music by Jared Paul – with additional tracks by Hannis Brown and Isaac Jones.

Thanks for listening.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.